Kitagawa Tamiji's Art and Art Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![French Journal of Japanese Studies, 4 | 2015, « Japan and Colonization » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Janvier 2015, Consulté Le 08 Juillet 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7806/french-journal-of-japanese-studies-4-2015-%C2%AB-japan-and-colonization-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-01-janvier-2015-consult%C3%A9-le-08-juillet-2021-67806.webp)

French Journal of Japanese Studies, 4 | 2015, « Japan and Colonization » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Janvier 2015, Consulté Le 08 Juillet 2021

Cipango - French Journal of Japanese Studies English Selection 4 | 2015 Japan and Colonization Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/cjs/949 DOI : 10.4000/cjs.949 ISSN : 2268-1744 Éditeur INALCO Référence électronique Cipango - French Journal of Japanese Studies, 4 | 2015, « Japan and Colonization » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 janvier 2015, consulté le 08 juillet 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/cjs/949 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/cjs.949 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 8 juillet 2021. Cipango - French Journal of Japanese Studies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. 1 SOMMAIRE Introduction Arnaud Nanta and Laurent Nespoulous Manchuria and the “Far Eastern Question”, 1880‑1910 Michel Vié The Beginnings of Japan’s Economic Hold over Colonial Korea, 1900-1919 Alexandre Roy Criticising Colonialism in pre‑1945 Japan Pierre‑François Souyri The History Textbook Controversy in Japan and South Korea Samuel Guex Imperialist vs Rogue. Japan, North Korea and the Colonial Issue since 1945 Adrien Carbonnet Cipango - French Journal of Japanese Studies, 4 | 2015 2 Introduction Arnaud Nanta and Laurent Nespoulous 1 Over one hundred years have now passed since the Kingdom of Korea was annexed by Japan in 1910. It was inevitable, then, that 2010 would be an important year for scholarship on the Japanese colonisation of Korea. In response to this momentous anniversary, Cipango – Cahiers d’études japonaises launched a call for papers on the subject of Japan’s colonial past in the spring of 2009. 2 Why colonisation in general and not specifically relating to Korea? Because it seemed logical to the journal’s editors that Korea would be the focus of increased attention from specialists of East Asia, at the risk of potentially forgetting the longer—and more obscure—timeline of the colonisation process. -

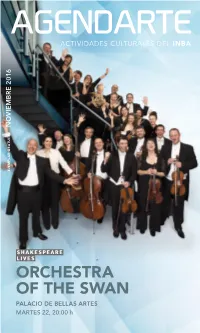

Orchestra of the Swan

NOVIEMBRE 2016 NOVIEMBRE EJEMPLAR GRATUITO EJEMPLAR ORCHESTRA OF THE SWAN PALACIO DE BELLAS ARTES MARTES 22, 20:00 h FRANCISCO DE GOYA ÚNICO Y ETERNO MUSEO NACIONAL DE SAN CARLOS DEL VIERNES 11 DE NOVIEMBRE AL LUNES 20 DE MARZO, 2017 DIRECTORIO NOVIEMBRE 2016 Secretaría de Cultura Rafael Tovar y de Teresa SECRETARIO Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes María Cristina García Cepeda DIRECTORA GENERAL ÍNDICE Sergio Ramírez Cárdenas SUBDIRECTOR GENERAL DE BELLAS ARTES Xavier Guzmán Urbiola SUBDIRECTOR GENERAL DEL PATRIMONIO ARTÍSTICO INMUEBLE 2 PALACIO DE BELLAS ARTES Jorge Gutiérrez Vázquez PBA SUBDIRECTOR GENERAL DE EDUCACIÓN E INVESTIGACIÓN ARTÍSTICAS Ana Lorena Mendoza Hinojosa 5 TEATRO SUBDIRECTORA GENERAL DE ADMINISTRACIÓN Roberto Perea Cortés DIRECTOR DE DIFUSIÓN Y RELACIONES PÚBLICAS 10 DANZA PROGRAMACIÓN SUJETA A CAMBIOS Año XIII, núm.10 13 MÚSICA noviembre 2016. Cartelera mensual de distribución gratuita que edita la Dirección de Difusión y Relaciones Públicas del INBA. Reforma y Campo Marte, Módulo A, 1er. piso, col. 22 LITERATURA Chapultepec Polanco, C.P. 11560, Ciudad de México. Comentarios: [email protected] MUSEOS Tiraje: 5,000 ejemplares 27 45 NIÑOS 2 NOVIEMBREPBA SUEÑO DE UNA NOCHE DE VERANO COMPAÑÍA NACIONAL DE DANZA SALA PRINCIPAL PALACIO DE BELLAS ARTES SÁBADO 19, 13:00 Y 19:00 h DOMINGOS 20* Y 27*, 17:00 h JUEVES 24*, 20:00 h *CON EL CORO Y LA ORQUESTA DEL TEATRO DE BELLAS ARTES PALACIO DE BELLAS ARTES 3 ÓPERA La Bohème (Reposición) De Giacomo Puccini Director concertador: Enrique Patrón de Rueda Director de escena: Luis -

The Reconstruction of Colonial Monuments in the 1920S and 1930S in Mexico ELSA ARROYO and SANDRA ZETINA

The reconstruction of Colonial monuments in the 1920s and 1930s in Mexico ELSA ARROYO AND SANDRA ZETINA Translation by Valerie Magar Abstract This article presents an overview of the criteria and policies for the reconstruction of historical monuments from the viceregal period in Mexico, through the review of paradigmatic cases which contributed to the establishment of practices and guidelines developed since the 1920s, and that were extended at least until the middle of the last century. It addresses the conformation of the legal framework that gave rise to the guidelines for the protection and safeguard of built heritage, as well as the context of reassessment of the historical legacy through systematic studies of representative examples of Baroque art and its ornamental components, considered in a first moment as emblematic of Mexico’s cultural identity. Based on case studies, issues related to the level of reconstruction of buildings are discussed, as well as the ideas at that time on the historical value of monuments and their function; and finally, it presents the results of the interventions in terms of their ability to maintain monuments as effective devices for the evocation of the past through the preservation of its material remains. Keywords: reconstruction, viceregal heritage, neo-Colonial heritage Background: the first piece of legislation on monuments as property of the Mexican nation While the renovation process of the Museo Nacional was taking place in 1864 during the Second Empire (1863-1867) under the government of the Emperor Maximilian of Habsburg, social awareness grew about the value of objects and monuments of the past, as well as on their function as public elements capable of adding their share in the construction of the identity of the modern nation that the government intended to build in Mexico. -

Horizontes Procesos Y Novedades En La Creación Artística Y Cultural Horizontes, Procesos Y Novedades En La Creación Artística Y Cultural

Pamela S. Jiménez Draguicevic Hugo Chávez Mondragón Antonio Tostado Reyes (Coordinadores) +1#'4)'$-1+ Horizontes Procesos y novedades en la creación artística y cultural Horizontes, procesos y novedades en la creación artística y cultural Pamela S. Jiménez Draguicevic Hugo Chávez Mondragón Antonio Tostado Reyes (Coordinadores) Comité Editorial Dr. Eduardo Núñez Rojas Dra. Cristina Medellín Gómez Dra. Pamela Jiménez Draguicevic Dr. Fabián Giménez Gatto Dra. Alejandra Díaz Zepeda Dr. Juan Granados Valdéz M. en C. Silvia Pantoja Ruiz Dr. Sergio Rivera Guerrero M. en A. Hugo Chávez Mondragón Dra. Irma Fuentes Mata Índice Investigación, conocimiento y creación en el artista visual: Presentación.............................................................................................10 Estética de una experiencia propia con el vidrio.................................83 Dolores Julieta Buenrostro Rojas Transformaciones artísticas en la obra de Feliciano Peña.................13 Magali Barbosa Piza Hermenéutica y estética del asco, entre la animalidad y la humanidad.....................................................91 Necesidad escénica.........................................................................2 Enrique J. Rodríguez Bárcenas 3Benito Cañada Rangel La cultura artística desde la estética prudencial Espectáculos redituables.................................................................31 (una aproximación)...............................................................................99 Ana Cristina Medellín Gómez Juan Granados -

Look Toward the Mountain, Episode 6 Transcript

LOOK TOWARD THE MOUNTAIN, EPISODE 6 TRANSCRIPT ROB BUSCHER: Welcome to Look Toward the Mountain: Stories from Heart Mountain Incarceration Camp, a podcast series about life inside the Heart Mountain Japanese American Relocation Center in northwestern Wyoming during World War II. I’m your host, Rob Buscher. This podcast is presented by the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation and is funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. ROB BUSCHER: The sixth episode titled “Organizing Resistance” will explore how the Japanese American tradition of organizing evolved in camp to become a powerful resistance movement that dominated much of the Heart Mountain experience in its later years. INTRO THEME ROB BUSCHER: For much of history, Japanese traditional society was governed by the will of its powerful military warlords. Although in principle the shogun and his vassal daimyo ruled by force, much of daily life within the clearly delineated class system of Japanese society relied on consensus-building and mutual accountability. Similar to European Feudalism, the Japanese Han system created a strict hierarchy that privileged the high-born samurai class over the more populous peasantry who made up nearly 95% of the total population. Despite their low rank, food-producing peasants were considered of higher status than the merchant class, who were perceived to only benefit themselves. ROB BUSCHER: During the Edo period, peasants were organized into Gonin-gumi - groups of five households who were held mutually accountable for their share of village taxes, which were paid from a portion of the food they produced. If their gonin-gumi did not meet their production quota, all the peasants in their group would be punished. -

Studia 16-3-09 OK Minus Hal .Indd

Volume 16, Number 3, 2009 V o l u m e 16 , N u m b e r 3 , 2009 STINIAI$hIilIIKA ffi @ EDITORIAL BOARD: M. Quraish Shihab (UINJaharta) Taufk Abdulkh (LIPI Jakarta) Nur A. Fadhil Lubis (IAIN Sumatra Uara) M.C. Ricklefs (National Uniuersity of Singapore) Martin uan Bruinessen (Urecht Uniuersity) John R. Bouen (Vashington Uniaersity, St. Louis) M. Atho Mudzhar (UIN Jaharta) M. Kamal Hasan (Intemational Islamic Uniuersity, Kuak Lumpur) M. Bary Hooker (Austalian National Uniuersi4t, Autralia) Vi rginia M at h e s o n H o o h e r (Aut t ra lia n Natio na I Un iu e rs ity' Au s tra li a) EDITOR-]N.CHIEF Azytmardi Azra EDITORS Jajat Burhanudin Saiful Mujani Jamhari Fu'ad Jabali Oman Fathurabman ASSiSTANT TO THE EDITORS Setyadi Sulaiman Testriono ENGLISH LANGUAGE ADVISOR Dick uan der Meij ARABIC I-A.NGUAGE ADVISOR Nursamad COVER DESIGNER S. Prinka STUDIA ISLAMIKA QSSN 0215-0492) is a joumal published b1 the Centerfor the Studl of hkn and societ\ @PIM) UIN Syrif Hida\atulkh, Jabarta (STT DEPPEN No 129/SK/DITJEN/PPG/ STT/1976). It specializes in Indonesian Islamic studies in particulat and South-east.Asian Islamic Studies in general, and is intended to communicate original researches and cutrent issues on the subject. This journal wam| welcomes contributions from scholtrs of related dirciplines. All artictes pubtished do not necesaily represent the aieus of the journal, or other irctitutions to which it h afrliated. Thq are solely the uieus ofthe authors. The articles contained in this journal haue been refereed by the Board of Edirors. -

The Influence of Politics and Culture on English Language Education in Japan During World War II and the Occupation

The Influence of Politics and Culture on English Language Education in Japan During World War II and the Occupation by Mayumi Ohara Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Certificate of Original Authorship I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Production Note: Signature removed prior to publication. Mayumi Ohara 18 June, 2015 i Acknowledgement I owe my longest-standing debt of gratitude to my husband, Koichi Ohara, for his patience and support, and to my families both in Japan and the United States for their constant support and encouragement. Dr. John Buchanan, my principal supervisor, was indeed helpful with valuable suggestions and feedback, along with Dr. Nina Burridge, my alternate supervisor. I am thankful. Appreciation also goes to Charles Wells for his truly generous aid with my English. He tried to find time for me despite his busy schedule with his own work. I am thankful to his wife, Aya, too, for her kind understanding. Grateful acknowledgement is also made to the following people: all research participants, the gatekeepers, and my friends who cooperated with me in searching for potential research participants. I would like to dedicate this thesis to the memory of a research participant and my friend, Chizuko. -

Discourse on Food in World War II Japan

ISSN: 1500-0713 ______________________________________________________________ Article Title: Discourse on Food in World War II Japan Author(s): Junko Baba Source: Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XXI (2017), pp. 131-153 Stable URL: https://asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan- studies-review/journal-archive/volume-xxi-2017/baba-junko- revision-710-corrections-added.pdf ______________________________________________________________ DISCOURSE ON FOOD IN WORLD WAR II JAPAN Junko Baba University of South Carolina Between a high, solid wall and an egg that breaks against it, I will always stand on the side of the egg. The eggs are the unarmed civilians who are crushed and burned and shot by them… And each of us, to a greater or lesser degree, is confronting a high, solid wall. The wall has a name: It is The System. The System is supposed to protect us, but sometimes it takes on a life of its own and then it begins to kill us and cause us to kill others - coldly, efficiently, systematically. – Haruki Murakami Food consumption during wartime is not only the usual fundamental source of energy, especially for soldiers in combat; it is also “an important home-front weapon essential for preserving order and productivity” of the citizens.1 This study analyzes the sociopolitical and cultural meaning of food in Japan during World War II by examining social commentary and criticism implied in selected post-war literature about the war by popular writers, when the role of food during wartime in the lives of ordinary citizens could be depicted without censorship. These literary works offer insight into the inner lives and conflicts of ordinary Japanese citizens, including civilians and conscripted soldiers, under the fascist military regime during the war. -

The Comic Artist As a Post-War Popular Critic of Imperial Japan

STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY Department of Asian, Middle Eastern and Turkish Studies The Comic Artist as a Post-war Popular Critic of Japanese Imperialism An Analysis of Nakazawa Keiji’s Hadashi no Gen Bachelor Thesis in Japanese Studies Spring Term 2015 Annika Bell Thesis Advisor: Misuzu Shimotori 1 Table of Contents Conventions ......................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ...................................................................... 4 Objectives and Research Question ....................................... 4 2. Background ....................................................................... 5 2.1 History of Imperial Japan ................................................... 5 2.2 Characteristics of Japanese Imperialism ..................... 8 2.3 Role of Popular Culture in Japan .................................. 10 2.4 Hadashi no Gen ..................................................................... 11 3. Material and Methodology ........................................ 14 4. Analysis and Results .................................................... 15 4.1 Imperial Japan in Hadashi no Gen ................................ 15 4.2 Hadashi no Gen and Norakuro ........................................ 19 4.3 Statistics ................................................................................. 22 5. Conclusion ..................................................................... 23 6. Summary ....................................................................... 24 7. Bibliography -

Japan's National Imagery of the “Holy War,”

SENSÔ SAKUSEN KIROKUGA (WAR CAMPAIGN DOCUMENTARY PAINTING): JAPAN’S NATIONAL IMAGERY OF THE “HOLY WAR,” 1937-1945 by Mayu Tsuruya BA, Sophia University, 1985 MA, University of Oregon, 1992 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2005 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Mayu Tsuruya It was defended on April 26, 2005 and approved by Karen M. Gerhart Helen Hopper Katheryn M. Linduff Barbara McCloskey J. Thomas Rimer Dissertation Director ii Copyright © by Mayu Tsuruya 2005 iii Sensô Sakusen Kirokuga (War Campaign Documentary Painting): Japan’s National Imagery of the “Holy War,” 1937-45 Mayu Tsuruya University of Pittsburgh, 2005 This dissertation is the first monographic study in any language of Japan’s official war painting produced during the second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 through the Pacific War in 1945. This genre is known as sensô sakusen kirokuga (war campaign documentary painting). Japan’s army and navy commissioned noted Japanese painters to record war campaigns on a monumental scale. Military officials favored yôga (Western-style painting) for its strength in depicting scenes in realistic detail over nihonga (Japanese-style painting). The military gave unprecedented commissions to yôga painters despite the fact that Japan was fighting the “materialist” West. Large military exhibitions exposed these paintings to civilians. Officials attached national importance to war documentary paintings by publicizing that the emperor had inspected them in the Imperial Palace. This study attempts to analyze postwar Japanese reluctance to tackle war documentary painting by examining its controversial and unsettling nature. -

Catalogo De Las Exposiciones De Arte En 1953

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.1954.sup1.2475 JUSTINO FERNANDEZ CATALOGO DE LAS EXPOSICIONES DE ARTE EN 1953 SUPLEMENTO DEL NUM. 22 DE LOS ANALES DEL INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES ESTETICAS MEXICO 1 9 5 4. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.1954.sup1.2475 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.1954.sup1.2475 Merece a todas luces el lugar de honor de las exposiciones capitalinas del afio de 1953 la Exposicion de Ayte Mesicano, instal ada en el Palacio de Bellas Artes por el Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y en 'la que colaboraron tanto el Insltituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, como el Instituto Nacional Indigenista. La instalaci6n, que ocupa practicamente todas las salas de exhibicion del edificio, es decir, 10 que constituye el Museo Nacional de Artes Plasticas, es excelente no obs tante su dificil realizacion, por 10 que merecen una felicitacion todos los encar gados de Ilevarla a cabo. En realidad no desmerece esta exposicion respecto a las que fueron presentadas en 1952 en Paris, Estocolmo y Londres; cierto que algunas piezas se suprimieron, mas, en carnbio se ha enriquecido con otras y, adernas, se ha contado con las obras murales de Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros y Tamayo que com pletan la seccion del arte contemporaneo, Alguna seccion resulta un poco exigua, me refiero a la de la pintura del siglo XIX, mas, en verdad, no era posible segura mente disponer de mayor espacio, Es de lamentar que no se haya publicado un ca talogo detallado de la exposicion cornpleta, pues la guia con que se cuenta no es suficiente para la visita ni para conmernorar tan magno suceso artistico. -

ESTA SEMANA, El Público Podrá Disfrutar En Alta Definición, Con

Dirección de Difusión y Relaciones Públicas Subdirección de Prensa ESTA SEMANA, el público podrá disfrutar en alta definición, con sonido digital y de manera gratuita diversas actividades artísticas en la pantalla gigante ubicada en el corredor Ángela Peralta, a un costado del Palacio de Bellas Artes. El sábado 1 a las 13:00 se retransmitirá L´histoire de Manon, interpretada por el Ballet de la Ópera de París desde el Palacio Garnier. [email protected] Dirección de Difusión y Relaciones Públicas Subdirección de Prensa MÁS TARDE, a las 20:00, el público podrá disfrutar de la proyección en vivo del Concierto de gala: 100 años de El Universal, desde la Sala Principal del recinto de mármol. Además, el miércoles 5 y el jueves 6 a las 20:00 se trasmitirán en vivo las primeras dos sesiones de la integral de las sinfonías de Ludwig van Beethoven que ofrecerá la Orquesta Barroca de Friburgo: las sinfonías núm. 1 y 2, y las sinfonías núm. 4 y 3, Heroica, respectivamente. Tanto el Concierto de gala como los de la Orquesta Barroca de Friburgo también podrán seguirse vía streaming en la liga livestream.com/inba y en el sitio web del INBA (www.bellasartes.gob.mx). [email protected] Dirección de Difusión y Relaciones Públicas Subdirección de Prensa EL PRIMER EPISODIO de la tercera temporada de la serie documental Artes, coproducción del INBA y Canal Once, se repetirá el domingo 2 a las 17:30 por la señal del Instituto Politécnico Nacional. Esta primera emisión está dedicada a Nacho López y a Carlos Jiménez Mabarak.