Fritz Lang in Hollywood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ein Deutsches Nibelungen-Triptychon. Die Nibelungenfilme Und Der Deutschen Not

Jörg Hackfurth (Gießen) Ein deutsches Nibelungen-Triptychon. Die Nibelungenfilme und der Deutschen Not 1. Einleitung In From Caligari to Hitler formuliert der Soziologe Siegfried Kracauer die These, daß „mittels einer Analyse der deutschen Filme tiefenpsychologi- sche Dispositionen, wie sie in Deutschland von 1918 bis 1933 herrschten, aufzudecken sind: Dispositionen, die den Lauf der Ereignisse zu jener Zeit beeinflussen und mit denen in der Zeit nach Hitler zu rechnen sein wird".1 Kracauers analytische Methode beruht auf einigen Prämissen, die hier noch einmal in ihrem originalen Wortlaut wiedergegeben werden sollen: „Die Filme einer Nation reflektieren ihre Mentalität unvermittelter als an- dere künstlerische Medien, und das aus zwei Gründen: Erstens sind Filme niemals das Produkt eines Individuums. [...] Da jeder Filmproduktionsstab eine Mischung heterogener Interessen und Neigungen verkörpert, tendiert die Teamarbeit auf diesem Gebiet dazu, willkürliche Handhabung des Filmmaterials auszuschließen und individuelle Eigenheiten zugunsten jener zu unterdrücken, die vielen Leuten gemeinsam sind. Zweitens richten sich Filme an die anonyme Menge und sprechen sie an. Von populären Filmen [...] ist daher anzunehmen, daß sie herrschende Massenbedürfnisse befrie- digen“2 Daraus resultiert ein Mechanismus, der sowohl in Hollywood als auch in Deutschland Geltung hat: „Hollywood kann es sich nicht leisten, Sponta- neität auf Seiten des Publikums zu ignorieren. Allgemeine Unzufriedenheit zeigt sich in rückläufigen Kasseneinnahmen, und die Filmindustrie, für die Profitinteresse eine Existenzfrage ist, muß sich so weit wie möglich den Veränderungen des geistigen Klimas anpassen".3 Ferner gilt: „Was die Filme reflektieren, sind weniger explizite Überzeu- gungen als psychologische Dispositionen – jene Tiefenschichten der Kol- lektivmentalität, die sich mehr oder weniger unterhalb der Bewußtseins- dimension erstrecken. -

Xx:2 Dr. Mabuse 1933

January 19, 2010: XX:2 DAS TESTAMENT DES DR. MABUSE/THE TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE 1933 (122 minutes) Directed by Fritz Lang Written by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou Produced by Fritz Lanz and Seymour Nebenzal Original music by Hans Erdmann Cinematography by Karl Vash and Fritz Arno Wagner Edited by Conrad von Molo and Lothar Wolff Art direction by Emil Hasler and Karll Vollbrecht Rudolf Klein-Rogge...Dr. Mabuse Gustav Diessl...Thomas Kent Rudolf Schündler...Hardy Oskar Höcker...Bredow Theo Lingen...Karetzky Camilla Spira...Juwelen-Anna Paul Henckels...Lithographraoger Otto Wernicke...Kriminalkomissar Lohmann / Commissioner Lohmann Theodor Loos...Dr. Kramm Hadrian Maria Netto...Nicolai Griforiew Paul Bernd...Erpresser / Blackmailer Henry Pleß...Bulle Adolf E. Licho...Dr. Hauser Oscar Beregi Sr....Prof. Dr. Baum (as Oscar Beregi) Wera Liessem...Lilli FRITZ LANG (5 December 1890, Vienna, Austria—2 August 1976,Beverly Hills, Los Angeles) directed 47 films, from Halbblut (Half-caste) in 1919 to Die Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse (The Thousand Eye of Dr. Mabuse) in 1960. Some of the others were Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), The Big Heat (1953), Clash by Night (1952), Rancho Notorious (1952), Cloak and Dagger (1946), Scarlet Street (1945). The Woman in the Window (1944), Ministry of Fear (1944), Western Union (1941), The Return of Frank James (1940), Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (The Crimes of Dr. Mabuse, Dr. Mabuse's Testament, There's a good deal of Lang material on line at the British Film The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse, 1933), M (1931), Metropolis Institute web site: http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/lang/. -

Close-Up on the Robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Close-up on the robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926 The robot of Metropolis The Cinémathèque's robot - Description This sculpture, exhibited in the museum of the Cinémathèque française, is a copy of the famous robot from Fritz Lang's film Metropolis, which has since disappeared. It was commissioned from Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, the sculptor of the original robot, in 1970. Presented in walking position on a wooden pedestal, the robot measures 181 x 58 x 50 cm. The artist used a mannequin as the basic support 1, sculpting the shape by sawing and reworking certain parts with wood putty. He next covered it with 'plates of a relatively flexible material (certainly cardboard) attached by nails or glue. Then, small wooden cubes, balls and strips were applied, as well as metal elements: a plate cut out for the ribcage and small springs.’2 To finish, he covered the whole with silver paint. - The automaton: costume or sculpture? The robot in the film was not an automaton but actress Brigitte Helm, wearing a costume made up of rigid pieces that she put on like parts of a suit of armour. For the reproduction, Walter Schulze-Mittendorff preferred making a rigid sculpture that would be more resistant to the risks of damage. He worked solely from memory and with photos from the film as he had made no sketches or drawings of the robot during its creation in 1926. 3 Not having to take into account the morphology or space necessary for the actress's movements, the sculptor gave the new robot a more slender figure: the head, pelvis, hips and arms are thinner than those of the original. -

Page 1 of 3 Moma | Press | Releases | 1998 | Gallery Exhibition of Rare

MoMA | press | Releases | 1998 | Gallery Exhibition of Rare and Original Film Posters at ... Page 1 of 3 GALLERY EXHIBITION OF RARE AND ORIGINAL FILM POSTERS AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART SPOTLIGHTS LEGENDARY GERMAN MOVIE STUDIO Ufa Film Posters, 1918-1943 September 17, 1998-January 5, 1999 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Lobby Exhibition Accompanied by Series of Eight Films from Golden Age of German Cinema From the Archives: Some Ufa Weimar Classics September 17-29, 1998 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Fifty posters for films produced or distributed by Ufa, Germany's legendary movie studio, will be on display in The Museum of Modern Art's Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Lobby starting September 17, 1998. Running through January 5, 1999, Ufa Film Posters, 1918-1943 will feature rare and original works, many exhibited for the first time in the United States, created to promote films from Germany's golden age of moviemaking. In conjunction with the opening of the gallery exhibition, the Museum will also present From the Archives: Some Ufa Weimar Classics, an eight-film series that includes some of the studio's more celebrated productions, September 17-29, 1998. Ufa (Universumfilm Aktien Gesellschaft), a consortium of film companies, was established in the waning days of World War I by order of the German High Command, but was privatized with the postwar establishment of the Weimar republic in 1918. Pursuing a program of aggressive expansion in Germany and throughout Europe, Ufa quickly became one of the greatest film companies in the world, with a large and spectacularly equipped studio in Babelsberg, just outside Berlin, and with foreign sales that globalized the market for German film. -

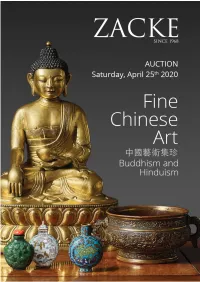

Catazacke 20200425 Bd.Pdf

Provenances Museum Deaccessions The National Museum of the Philippines The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University New York, USA The Monterey Museum of Art, USA The Abrons Arts Center, New York, USA Private Estate and Collection Provenances Justus Blank, Dutch East India Company Georg Weifert (1850-1937), Federal Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia Sir William Roy Hodgson (1892-1958), Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, OBE Jerrold Schecter, The Wall Street Journal Anne Marie Wood (1931-2019), Warwickshire, United Kingdom Brian Lister (19262014), Widdington, United Kingdom Léonce Filatriau (*1875), France S. X. Constantinidi, London, United Kingdom James Henry Taylor, Royal Navy Sub-Lieutenant, HM Naval Base Tamar, Hong Kong Alexandre Iolas (19071987), Greece Anthony du Boulay, Honorary Adviser on Ceramics to the National Trust, United Kingdom, Chairman of the French Porcelain Society Robert Bob Mayer and Beatrice Buddy Cummings Mayer, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago Leslie Gifford Kilborn (18951972), The University of Hong Kong Traudi and Peter Plesch, United Kingdom Reinhold Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria Sir Thomas Jackson (1841-1915), 1st Baronet, United Kingdom Richard Nathanson (d. 2018), United Kingdom Dr. W. D. Franz (1915-2005), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Josette and Théo Schulmann, Paris, France Neil Cole, Toronto, Canada Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald (19021982) Arthur Huc (1854-1932), La Dépêche du Midi, Toulouse, France Dame Eva Turner (18921990), DBE Sir Jeremy Lever KCMG, University -

German Films

IP THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 11 WEST 53 STREET. NEW YORK 19. N. Y. TILIFHONI: CIICLI S-8f00 No. lUl FOR RELEASE: Sunday, December 8, 1957 FISCHINGER AND FRITZ LANG FILMS AT MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Another abstract film by Oskar Fischinger, Studie No. 11, and Fritz Lang's The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse (Das Testament des Mr. Mabuse) will be the 5 and 5:30 daily showings December 8 - 11 at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street. It is the current program in the series "Past and Present: A Selection of German Films, 1896 - 1957." Studie No. 11 (1932), abstract forms set to a minuet by Mozart, is an early experiment in the long sequence of "absolute films" still being made by Fischinger. Constructed under an esthetic disipline which regards people, settings and plot as extraneous, pattern, space, motion and rhythm are the only elements involved. A melodrama of a madman's plot to conquer the world through terrorism, The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse (1933) was the last film made by Fritz Lang in Germany. It was immediately banned by the Nazis. Lang, long considered a master in the treatment of psychological aberrations (M, Metropolis, Fury) said of Dr. Mabuse: "This film was made as an allegory, to show Hitler's processes of terrorism. Slo gans and doctrines of the Third Reich have been put into the mouths of criminals in the film..Thus I hoped to expose the masked Nazi theory of the necessity to de liberately destroy everything which is precious to a people so that they would lose all-.faith in the institutions and ideals of the State. -

From Iron Age Myth to Idealized National Landscape: Human-Nature Relationships and Environmental Racism in Fritz Lang’S Die Nibelungen

FROM IRON AGE MYTH TO IDEALIZED NATIONAL LANDSCAPE: HUMAN-NATURE RELATIONSHIPS AND ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM IN FRITZ LANG’S DIE NIBELUNGEN Susan Power Bratton Whitworth College Abstract From the Iron Age to the modern period, authors have repeatedly restructured the ecomythology of the Siegfried saga. Fritz Lang’s Weimar lm production (released in 1924-1925) of Die Nibelungen presents an ascendant humanist Siegfried, who dom- inates over nature in his dragon slaying. Lang removes the strong family relation- ships typical of earlier versions, and portrays Siegfried as a son of the German landscape rather than of an aristocratic, human lineage. Unlike The Saga of the Volsungs, which casts the dwarf Andvari as a shape-shifting sh, and thereby indis- tinguishable from productive, living nature, both Richard Wagner and Lang create dwarves who live in subterranean or inorganic habitats, and use environmental ideals to convey anti-Semitic images, including negative contrasts between Jewish stereo- types and healthy or organic nature. Lang’s Siegfried is a technocrat, who, rather than receiving a magic sword from mystic sources, begins the lm by fashioning his own. Admired by Adolf Hitler, Die Nibelungen idealizes the material and the organic in a way that allows the modern “hero” to romanticize himself and, with- out the aid of deities, to become superhuman. Introduction As one of the great gures of Weimar German cinema, Fritz Lang directed an astonishing variety of lms, ranging from the thriller, M, to the urban critique, Metropolis. 1 Of all Lang’s silent lms, his two part interpretation of Das Nibelungenlied: Siegfried’s Tod, lmed in 1922, and Kriemhilds Rache, lmed in 1923,2 had the greatest impression on National Socialist leaders, including Adolf Hitler. -

Metropolis Um Filme De Fritz Lang 1927

CICLO INTEGRADO DE CINEMA, DEBATES E COLÓQUIOS NA FEUC DOC TAGV / FEUC INTEGRAÇÃO MUNDIAL, DESINTEGRAÇÃO NACIONAL: A CRISE NOS MERCADOS DE TRABALHO METROPOLIS UM FILME DE FRITZ LANG 1927 CICLO INTEGRADO DE CINEMA, DEBATES E COLÓQUIOS NA FEUC DOC TAGV / FEUC INTEGRAÇÃO MUNDIAL, DESINTEGRAÇÃO NACIONAL: A CRISE NOS MERCADOS DE TRABALHO http://www4.fe.uc.pt/ciclo_int/2007_2008.htm SESSÃO 14 (SESSÃO DE ENCERRAMENto) METROPOLIS: UMA ANTEVISÃO DA EUROPA ACTUAL? METROPOLIS (1927) UM FILME DE FRITZ LANG DEBate COM: JEAN-MICHEL MEURICE (CINeasta) MANUEL PORTELA (FLUC) JOSÉ ANTÓNIO BANDEIRINHA (PRÓ-REItoR UC) TeatRO ACADÉMICO DE GIL VICENTE 2 DE JULHO DE 2008 METROPOLIS: UMA ANTEVISÃO DA EUROPA ACTUAL? 1. METROPOLIS: A VISÃO DE ALGUNS cineastas 05 1.1. METROPOLIS, Visto POR FRITZ Lang 05 1.2. METROPOLIS, Visto POR Bunuel 08 1.3. METROPOLIS, Visto POR JOÃO BÉNARD DA Costa 11 1.4. Relatos DE UMA REALIZAÇÃo 15 2. LANG, METROPOLIS E A DIMENSÃO POLÍtica 17 2.1. METROPOLIS: UM FILME INTEMPoral 17 2.2. A LEITURA POLÍTICA DE UMA cena 30 3. METROPOLIS: ALGUMAS RECENSÕes 31 3.1. METROPOLIS, DE FRITZ Lang 31 3.2. METROPOLIS, SINOPse 35 3.3. METROPOLIS: O FILME MAIS INOVADOR DESDE A INVENÇÃO DO CINEMa 39 3.4. METROPOLIS: ALGUMAS BRECHas 41 3.5. COMENTÁRIOS DO LE MONDE SOBRE METROPOLIS 43 4. A FUGA DE Lang 48 5. METROPOLIS: UMA LEITURA DE SÍntese 50 CICLO INTEGRADO DE CINEMA, DEBATES E COLÓQUIOS NA FEUC DOC TAGV / FEUC INTEGRAÇÃO MUNDIAL, DESINTEGRAÇÃO NACIONAL: A CRISE NOS MERCADOS DE TRABALHO PROGRAMA 2007 - 2008 60 © Metropolis, 1927. METROPOLIS: UMA ANTEVISÃO DA EUROPA ACTUAL? 1. -

Joe May's Indian Tomb

Claudia Breger Performing Violence: Joe May’s Indian Tomb (1921) The article investigates the productivity of performance-theoretical approaches for the study of violence in German cultural history. My case study for this undertaking is Joe May’s popular Das Indische Grabmal [The Indian Tomb] (1921), through which I connect the theoretical argument to film-historical debates on Kracauer’s gene- alogies of fascist violence in Weimar cinema. Different approaches subsumed under the “performative turn” concur in the notion that performance wins its critical force by subverting narrative and representation. My close reading of the film begins by discussing two epistemologically divergent versions of this argument (performance as the presencing of the real vs. performance as the theatricalizing of representa- tion). While building on the latter argument, my own reading of Das Indische Grabmal nonetheless demonstrates that the complex workings of performance are better under- stood by reconceptualizing it as a force of (critical) re-contextualization, acting not necessarily against, but in and through narrative. Analyzing the film’s aesthetic of narrative performance ennables a reading of it as an artistic “Kritik der Gewalt” [“critique of violence”] (Benjamin), which, however, remains equivocally embedded in trans/national discourses of imperialist and racist violence. With roots in theater studies, linguistics, and anthropology as well as the aesthetic discourses of twentieth century avant-gardes, notions of performance have taken center stage -

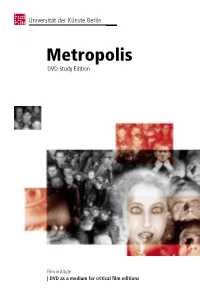

Metropolis DVD Study Edition

Metropolis DVD Study Edition Film institute | DVD as a medium for critical film editions 2 Table of Contents Preface | Heinz Emigholz 3 Preface | Hortensia Völckers 4 Preface | Friedemann Beyer 5 DVD: Old films, new readings | Enno Patalas 6 Edition of a torso | Anna Bohn 8 Le tableau disparu | Björn Speidel 12 Navigare necesse est | Gunter Krüger 15 Navigation-Model 18 New Tower Metropolis | Enno Patalas 20 Making the invisible “visible” | Franziska Latell & Antje Michna 23 Metropolis, 1927 | Gottfried Huppertz 26 Metropolis, 2005 | Mark Pogolski & Aljioscha Zimmermann 27 Metropolis – Synopsis 28 Film Specifications 29 Contributors 30 Imprint 33 Thanks 35 3 Preface Many versions and editions exist of the film Metropolis, dating back to its very first screening in 1927. Commercial distribution practice at the time of the premiere cut films after their initial screening and recompiled them according to real or imaginary demands. Even the technical requirements for production of different language versions of the film raise the question just which “original” is to be protected or reconstructed. In other fields of the arts the stature and authority that even a scratched original exudes is not given in the “history of film”. There may be many of the kind, and gene- rations of copies make only for a cluster of “originals”. Reconstruction work is therefore essentially also the perception of a com- plex and viable happening only to be understood in terms of a timeline – linear and simultaneous at one and the same time. The consumer’s wish for a re-constructible film history following regular channels and self-con- tained units cannot, by its very nature, be satisfied; it is, quite simply, not logically possible. -

Fritz Lang Und Genitiv-Schlüssel

Fritz Lang und Genitiv—Drehbuchautor, Regisseur, adaptiert von http://www.dhm.de/lemo/html/biografien/LangFritz/ Deutsch 4 Name______________________ Bitte die Lücken ergänzen, um das richtige Form des Genitivs zu machen. 1890 5. Dezember: Fritz Lang wird als Sohn des____ Architekten_____Anton Lang und dessen Frau Paula (geb. Schlesinger) in Wien geboren. 1907 Nach dem Besuch der___Realschule_/___ beginnt Lang auf Wunsch des_____Vaters____ ein Bauingenieurstudium an der Technischen Hochschule in Wien. 1908 Er wechselt zum Studium der______ Malerei__/__ an die Wiener Akademie der______ Graphischen_____ Künste ___/___. Neben dem Studium tritt er als Kabarettist auf. ab 1910 Er unternimmt größere Reisen, die ihn unter anderem in Mittelmeerländer und nach Afrika führen. 1911 Lang geht nach München, um an der Kunstgewerbeschule zu studieren. Dort bleibt er jedoch nur für kurze Zeit, da er wieder auf Reisen geht. 1913/14 Er setzt seine Ausbildung in Paris bei dem Maler Maurice Denis (1870-1943) fort. Durch das französische Kino findet er intensiven Zugang zum neuen Medium Film. 1914 Mit Beginn des_ Erst_en____ Welkrieg_es____ kehrt Lang nach Wien zurück, um sich als Kriegsfreiwilliger zu melden. 1916 Nach einer Kriegsverletzung kommt er zum Genesungsurlaub wieder nach Wien. Lang knüpft erste Kontakte zu Filmleuten und beginnt als Drehbuchautor zu arbeiten. 1917 Lang muß nach seiner Genesung an die Front zurück. 1918 Er wird nach einer zweiten Verwundung für kriegsuntauglich erklärt. Bei einem Schauspiel im Rahmen der_____ Truppenbetreuung___/____ arbeitet er zum ersten Mal als Regisseur. Lang siedelt nach Berlin über, um als Dramaturg tätig zu werden. 1919 Mit dem in fünf Tagen gedrehten Stummfilm "Halbblut" hat Lang sein Regiedebüt. -

Lang, Fritz , 1890–1976, German-American Film Director, B

Lang, Fritz , 1890–1976, German-American film director, b. Vienna. His silent and early sound films, such as Metropolis (1926), are marked by brilliant expressionist technique. He gained worldwide acclaim with M (1933), a study of a child molester and murderer. After directing 15 films, Lang fled Nazi Germany (1933) to avoid collaborating with the government and settled in the United States. His 20 Hollywood films continued his exploration of criminality and the cruel fate that can overtake the unwary. His notable American works include Fury (1936), You Only Live Once (1937), Hangmen Also Die (1943), The Big Heat (1953), and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956). Born in Vienna, Austria, Fritz Lang’s father managed a construction company. His mother, Pauline Schlesinger, was Jewish but converted to Catholicism when Lang was ten . After high school he enrolled briefly at the Technische Hochschule Wien, then started to train as a painter. From 1910 to 1914 he traveled in Europe and, he would later claim, also in Asia and North Africa. He studied painting in Paris in 1913-14. At the start of the First World War he returned to Vienna, enlisting in the army in January 1915. Severely injured in June 1916, he wrote some scenarios for films while convalescing. In early 1918 he was sent home shell-shocked and acted briefly in Viennese theater before accepting a job as a writer at Erich Pommer's production company in Berlin, Decla. In Berlin, Lang worked briefly as a writer and then as a director, at UFA and then for Nero-Film, owned by the American Seymour Nebenzahl.