Proceedings Exling 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romanian Language and Its Dialects

Social Sciences ROMANIAN LANGUAGE AND ITS DIALECTS Ana-Maria DUDĂU1 ABSTRACT: THE ROMANIAN LANGUAGE, THE CONTINUANCE OF THE LATIN LANGUAGE SPOKEN IN THE EASTERN PARTS OF THE FORMER ROMAN EMPIRE, COMES WITH ITS FOUR DIALECTS: DACO- ROMANIAN, AROMANIAN, MEGLENO-ROMANIAN AND ISTRO-ROMANIAN TO COMPLETE THE EUROPEAN LINGUISTIC PALETTE. THE ROMANIAN LINGUISTS HAVE ALWAYS SHOWN A PERMANENT CONCERN FOR BOTH THE IDENTITY AND THE STATUS OF THE ROMANIAN LANGUAGE AND ITS DIALECTS, THUS SUPPORTING THE EXISTENCE OF THE ETHNIC, LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL PARTICULARITIES OF THE MINORITIES AND REJECTING, FIRMLY, ANY ATTEMPT TO ASSIMILATE THEM BY FORCE KEYWORDS: MULTILINGUALISM, DIALECT, ASSIMILATION, OFFICIAL LANGUAGE, SPOKEN LANGUAGE. The Romanian language - the only Romance language in Eastern Europe - is an "island" of Latinity in a mainly "Slavic sea" - including its dialects from the south of the Danube – Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian and Istro-Romanian. Multilingualism is defined narrowly as the alternative use of several languages; widely, it is use of several alternative language systems, regardless of their status: different languages, dialects of the same language or even varieties of the same idiom, being a natural consequence of linguistic contact. Multilingualism is an Europe value and a shared commitment, with particular importance for initial education, lifelong learning, employment, justice, freedom and security. Romanian language, with its four dialects - Daco-Romanian, Aromanian, Megleno- Romanian and Istro-Romanian – is the continuance of the Latin language spoken in the eastern parts of the former Roman Empire. Together with the Dalmatian language (now extinct) and central and southern Italian dialects, is part of the Apenino-Balkan group of Romance languages, different from theAlpine–Pyrenean group2. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

The Vlachs of Greece and Their Misunderstood History Helen Abadzi1 January 2004

The Vlachs of Greece and their Misunderstood History Helen Abadzi1 January 2004 Abstract The Vlachs speak a language that evolved from Latin. Latin was transmitted by Romans to many peoples and was used as an international language for centuries. Most Vlach populations live in and around the borders of modern Greece. The word „Vlachs‟ appears in the Byzantine documents at about the 10th century, but few details are connected with it and it is unclear it means for various authors. It has been variously hypothesized that Vlachs are descendants of Roman soldiers, Thracians, diaspora Romanians, or Latinized Greeks. However, the ethnic makeup of the empires that ruled the Balkans and the use of the language as a lingua franca suggest that the Vlachs do not have one single origin. DNA studies might clarify relationships, but these have not yet been done. In the 19th century Vlach was spoken by shepherds in Albania who had practically no relationship with Hellenism as well as by urban Macedonians who had Greek education dating back to at least the 17th century and who considered themselves Greek. The latter gave rise to many politicians, literary figures, and national benefactors in Greece. Because of the language, various religious and political special interests tried to attract the Vlachs in the 19th and early 20th centuries. At the same time, the Greek church and government were hostile to their language. The disputes of the era culminated in emigrations, alienation of thousands of people, and near-disappearance of the language. Nevertheless, due to assimilation and marriages with Greek speakers, a significant segment of the Greek population in Macedonia and elsewhere descends from Vlachs. -

The Origin and Spread of Locative Determiner Omission in the Balkan Linguistic Area

The Origin and Spread of Locative Determiner Omission in the Balkan Linguistic Area by Eric Heath Prendergast A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Line Mikkelsen, Chair Professor Lev Michael Professor Ronelle Alexander Spring 2017 The Origin and Spread of Locative Determiner Omission in the Balkan Linguistic Area Copyright 2017 by Eric Heath Prendergast 1 Abstract The Origin and Spread of Locative Determiner Omission in the Balkan Linguistic Area by Eric Heath Prendergast Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Line Mikkelsen, Chair This dissertation analyzes an unusual grammatical pattern that I call locative determiner omission, which is found in several languages belonging to the Slavic, Romance, and Albanian families, but which does not appear to have been directly inherited from any individual genetic ancestor of these languages. Locative determiner omission involves the omission of a definite article in the context of a locative prepositional phrase, and stands out as a feature of the Balkan linguistic area for which there are few, if any crosslinguistic parallels. This investigation of the origin and diachronic spread of locative determiner omission serves the particular goal of revealing how the social context of language contact could have resulted in a pattern of grammatical borrowing without lexical borrowing, yielding a present distribution in which locative determiner omission appears in several Balkan languages no longer in direct contact with one another. A detailed structural and historical analysis of locative determiner omission in Albanian, Romanian, Aromanian, and Macedonian is used as a basis for comparison with other Balkan languages. -

93323765-Mack-Ridge-Language-And

Language and National Identity in Greece 1766–1976 This page intentionally left blank Language and National Identity in Greece 1766–1976 PETER MACKRIDGE 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Peter Mackridge 2009 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mackridge, Peter. -

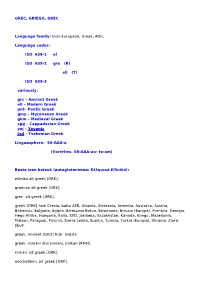

GREC, GRIEGO, GREC Language Family

GREC, GRIEGO, GREC Language family: Indo-European, Greek, Attic. Language codes: ISO 639-1 el ISO 639-2 gre (B) ell (T) ISO 639-3 variously: grc – Ancient Greek ell – Modern Greek pnt– Pontic Greek gmy – Mycenaean Greek gkm – Medieval Greek cpg – Cappadocian Greek yej – Yevanic tsd – Tsakonian Greek Linguasphere: 56-AAA-a (Varieties: 56-AAA-aa- to-am) Beste izen batzuk (autoglotonimoa: Ελληνικά Ellīniká): ellinika alt greek [GRK]. graecae alt greek [GRK]. grec alt greek [GRK]. greek [GRK] hizk Grezia; baita AEB, Albania, Alemania, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Bulgaria, Egipto, Erresuma Batua, Errumania, Errusia (Europa), Frantzia, Georgia, Hego Afrika, Hungaria, Italia, KED, Jordania, Kazakhstan, Kanada, Kongo, Mazedonia, Malawi, Paraguai, Polonia, Sierra Leona, Suedia, Tunisia, Turkia (Europa), Ukraina, Zipre, Jibuti. greek, ancient [GKO] hizk. Grezia. greek, romani dial romani, balkan [RMN]. romaic alt greek [GRK]. neo-hellenic alt greek [GRK]. ALBANIA greek [GRK] 60.000 hiztun, populazioaren % 1,8 (1989). Hegoaldea. Indo-European, Greek, Attic. Ikus sarrera nagusia Grezian. EGIPTO greek [GRK] 60.000 hiztun (1977, Voegelin and Voegelin). Alexandria. Indo-European, Greek, Attic. Ikus sarrera nagusia Grezian. ERRUMANIA greek [GRK] Indo-European, Greek, Attic. Karakatxanak grekos mintzatzen diren errumaniar artzain nomadak dira. GREZIA greek (ellinika, grec, graecae, romaic, neo-hellenic) [GRK] 9.859.850 hiztun, populazioaren % 98,5 (1986). Herrialde guztietako populazio osoa 12.000.000 (1999, WA). Herrialdean zehar. Halaber mintzatua beste 35 herrialdetan, hala nola AEB, Albania, Alemania, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Bulgaria, Egipto, Erresuma Batua, Errumania, Errusia (Europa), Frantzia, Georgia, Hego Afrika, Hungaria, Italia, KED, Jordania, Kazakhstan, Kanada, Kongo, Mazedonia, Malawi, Paraguai, Polonia, Sierra Leona, Suedia, Tunisia, Turkia (Europa), Ukraina, Zipre eta Jibutin ere. -

Analele Universit Ii Din Craiova

ANNALES DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE CRAÏOVA ANNALS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CRAIOVA ANALELE UNIVERSITII DIN CRAIOVA SERIA 1TIINWE FILOLOGICE LINGVISTIC: 5 ANUL XXXII, Nr. 1-2, 2010 EUC EDITURA UNIVERSITARIA R !" $%&"!'($ )"*$" " )""+"!'," !R & - . /- 01$%&'($ )"2 %"+" )") )$) ,!)+()! W Michel Francard Laurent Gautier Maria Iliescu (Louvain-la-Neuve) (Dijon) (Innsbruck) Ileana Oancea Elena Prus Marius Sala (Timişoara) (Chişinău) (Bucureşti) Fernando Sánchez Miret Flora Şuteu Federico Vicario (Salamanca) (Craiova) (Udine) Cristiana-Nicola Teodorescu – redactor-şef Elena Pîrvu – redactor-şef adjunct Ioana Murar Gabriela Scurtu Nicolae Panea Ştefan Vlăduţescu Ovidiu Drăghici, Melitta Szathmary – secretari de redacţie Cristina Bălosu – tehnoredactor CUPRINS Mirela AIOANE, La radio italiana e la sua importanza linguistica 13 Gabriela BIRIŞ, Neologie de sens în româna actuală 21 Ana-Maria BOTNARU, Verbe care exprimă intervenţia omului asupra pădurii 30 Iustina BURCI, Prenumele feminine – repere locale şi sociale în toponimia din Oltenia 35 Cecilia CONDEI, Hypo/hyper/co-discours: trois plans discursifs de l’étymologie sociale 45 Daniela CORBU-DOMŞA, Termeni entopici în structurile toponimice din Ţinutul Dornelor 55 Adriana COSTACHESCU, Quelques lexèmes en voyage (trajet français – anglais – roumain) 73 Daniela DINCĂ, Étude lexicographique et sémantique du gallicisme marchiz, -ă en roumain actuel 89 Cosmin DRAGOSTE, „Tâlhari” şi „hoţi” – aspecte ale traducerii în piesa Diebe de Dea Loher 97 Ilona DUŢĂ, Identitate şi nume propriu -

Fallacies and Facts on the Macedonian Issue ©2003 by Marcus a Templar

Fallacies & Facts on Macedonian Issue by Marcus A. Templar, 2003 FALLACIES AND FACTS ON THE MACEDONIAN ISSUE ©2003 BY MARCUS A TEMPLAR There have been certain fallacies circulating for the past few years due to ignorance on the “Macedonian Issue”. It is exacerbated by systematic propaganda emanating from AVNOJ, or communist Yugoslavia and present-day FYROM, and their intransigent ultra-nationalist Diaspora. Fallacy #1 The inhabitants of The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (The FYROM) are ethnic Macedonians, direct descendants of, or related to the ancient Macedonians. Fact #1 The inhabitants of The FYROM are mostly Slavs, Bulgarians and Albanians. They have nothing in common with the ancient Macedonians. Here are some testimonies from The FYROM’s officials: a. The former President of The FYROM, Kiro Gligorov said: “We are Slavs who came to this area in the sixth century ... we are not descendants of the ancient Macedonians" (Foreign Information Service Daily Report, Eastern Europe, February 26, 1992, p. 35). b. Also, Mr Gligorov declared: "We are Macedonians but we are Slav Macedonians. That's who we are! We have no connection to Alexander the Greek and his Macedonia… Our ancestors came here in the 5th and 6th century" (Toronto Star, March 15, 1992). c. On 22 January 1999, Ambassador of the FYROM to USA, Ljubica Achevska gave a speech on the present situation in the Balkans. In answering questions at the end of her speech Mrs. Acevshka said: "We do not claim to be descendants of Alexander the Great … Greece is Macedonia’s second largest trading partner, and its number one investor. -

The Vlachs, History, Language, Tradition at the End of 3Rd B.C

The Vlachs, History, Language, Tradition At the end of 3rd B.C. century, in the Balkans, there were future events that would play a decisive role in the future for Greeks and the formation of the Balkan languages. In the wars against the Illyrians, the Romans found the cause for their intervention in the Balkans and the materialization of their conquest plans. From the very beginning of the presence of the Roman troops in the Balkan Peninsula, the penetration of the Latin language begins in the Greek and Balkan area. In 146 BC Greece is submitted officially to the Romans and it is organized as a Roman province. Years passed and the capital of the Roman Empire moved to Constantinople. The language of the army, government, courts and the imperial court was Latin, although the majority of people were Greek-speaking. The struggle between the two languages was unequal and the cultural superiority of the Greeks preserved their body language (Greek). The effect from the Latin to the Greek language was minimal and it was mainly related to vocabulary, while loss in speakers, such as the Vlachs/Armanians, who are enlatinized Greeks, was not significant. The enlatinization found appropriate ‘ground’ to isolated and mountainous populations, who early associated their lives and occupations with the Roman administration and army, since they were subject to the Roman state, cooperated to it ,as carriers and feeders, detached from Greek education and civilization centers. The use of Latin language in government and army dominated until early 6th century A.C. According to Ioannis Lydos (6th century), a Byzantine officer, the language of public officials and citizens, largely in parts of Greece, was Latin. -

Predrag Mutavdžić* University of Belgrade, Faculty of Philology Serbia

Mutavdžić, P.: On the Former and Present Status of the Aromanian Language... 146 Komunikacija i kultura online: Godina I, broj 1, 2010. Predrag Mutavdžić* University of Belgrade, Faculty of Philology Serbia ОN THE FORMER AND PRESENT STATUS OF THE AROMANIAN LANGUAGE IN THE BALKAN PENINSULA AND IN EUROPE Original scientific paper UDC 811.135.1'282.4(497) This paper gives a brief historical overview of linguistic surveys (Romance and Romanian linguistics) of the status of Aromanian within Romance language linguistics and Balkan linguistic area. Until quite recently, relevant linguists considered this language to be merely a dialect of Daco-Romanian, while today it is generally seen as an autonomous Balkan Romance language. The fact that this language, apart from having a considerably large number of native speakers, especially in their homelands, is little known to general public in the Balkans and in Europe. Key words: Aromanian, pan-Romanianism, Romance languages in the Balkans, endangered languages, Romanian propaganda Current linguistic trends in Europe are quite liberal when compared to those from the past. From a historical point of view and considering the overall development of human society, it seems to have been necessary for Europe to openly face numerous and daunting challenges in many fields, and particularly in those concerning ethnic, linguistic and cultural features of a nation, which caused the aforementioned change. The turbulent 1930s and the Second World War gave rise to challenges which put to test Europe‟s commitment to democracy, principles of freedom, equality and fraternity and to respect all national, human and civil rights. Lessons which came from one of the most turbulent epochs in modern history of this continent radically changed the attitude of European nations toward themselves and other nations. -

Auxiliary Schedule 3 : Language

AUXILIARY SCHEDULE 3 : LANGUAGE (1) This separate schedule is an auxiliary to the enumerated classes 2/9, A/Z. The concepts in it are available only to qualify those classes, and their classmarks are not to be used on their own. (2) These classmarks may be added to any class where the instruction appears to add letters from Schedule 3; e.g. in Class J Education, JV is special categories of educands, and at JVG Language groups, Non-English (or favoured language) speaking appears the instruction: Add to JVG letters C/Z from Schedule 3; so Education of Bantus would be JVG HN. Or, in Schedule 2, BQ is Linguistic group areas, and BQH N would be Bantu-speaking areas. (3) A prominent use of the Schedule will be to specify translations, version, etc., of particular works in classes like Literature, Religion and Philosophy; e.g. PM6 Versions of the New Testament, has the instruction Add to PM6 letters C/Z from Schedule 3; so PM6 RF is Greek versions. (4) Where no such special provision is made, the language of a document can be specified by adding Schedule 3 notation to 2X from Schedule 1, e.g. Encyclopaedia of economics, in French T3A 2XV. (5) If a library wishes to give a preferred position with a short classmark to a particular language (e.g. that of the place where the library is situated) the letter F or Z may be used. (6) Any language may be qualified by the preceding arrays C/E by direct retroactive synthesis; e.g. -

The Academic Dictionary of the Romanian Language (Dicţionarul Academic Al Limbii Române – DLR) Lexicological Relevance and Romanic Context

The Academic Dictionary of the Romanian Language (Dicţionarul academic al Limbii Române – DLR) Lexicological Relevance and Romanic Context Cristina FLORESCU Key-words: Romanian lexis, etymological dictionary, Romanian Academic lexicography, Romance lexicography. 1. Quantitative values of the Romanian lexis in DLR The academician Marius Sala, main editor of the Dictionary of the Romanian Language (DLR) [Rom. Dicţionarul limbii române], stated, in the Preface to The Small Academic Dictionary (MDA) [Micul dicţionar academic] published in 2001, that this lexicon contained, in its four volumes, 170.000 words and variants. Starting from his assessment, we can estimate the number of words (articles and variants) to be included in the complete version of the DLR (from A to Z) after bringing up-to date and enriching the older series of the Dictionary of the Academy (DA). Therefore, we can compare lists of words and numeric estimations of the lexemes in our language. For instance, we can parallel the list of all the lexemes beginning with C in the MDA volumes with the provisional list of words beginning with C elaborated by the lexicographers in Iaşi (to be included in the future volume of the DLR). By analyzing such correlations, we can approximate that the number of entries (lexicographic articles and lexical variants) in the future unified and up-to- date DLR will come close to 200.000 lexical elements. In 1999, the lexicographers in Iaşi were elaborating six DLR volumes containing words / articles in various work stages: sampling, research, lexicographic diagrams, drafting, partial revision, intermediary version, final revision, final rewriting, completion for the Etymologies Commission.