Maori Gardening: an Archaeological Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Arboreal Heritage for Twenty-First-Century Aotearoa New Zealand

NATURAL MONUMENTS: RETHINKING ARBOREAL HERITAGE FOR TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND Susette Goldsmith A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2018 ABSTRACT The twenty-first century is imposing significant challenges on nature in general with the arrival of climate change, and on arboreal heritage in particular through pressures for building expansion. This thesis examines the notion of tree heritage in Aotearoa New Zealand at this current point in time and questions what it is, how it comes about, and what values, meanings and understandings and human and non-human forces are at its heart. While the acknowledgement of arboreal heritage can be regarded as the duty of all New Zealanders, its maintenance and protection are most often perceived to be the responsibility of local authorities and heritage practitioners. This study questions the validity of the evaluation methods currently employed in the tree heritage listing process, tree listing itself, and the efficacy of tree protection provisions. The thesis presents a multiple case study of discrete sites of arboreal heritage that are all associated with a single native tree species—karaka (Corynocarpus laevigatus). The focus of the case studies is not on the trees themselves, however, but on the ways in which the tree sites fill the heritage roles required of them entailing an examination of the complicated networks of trees, people, events, organisations, policies and politics situated within the case studies, and within arboreal heritage itself. Accordingly, the thesis adopts a critical theoretical perspective, informed by various interpretations of Actor Network Theory and Assemblage Theory, and takes a ‘counter-’approach to the authorised heritage discourse introducing a new notion of an ‘unauthorised arboreal heritage discourse’. -

New Zealand Wine Fair Sa N Francisco 2013 New Zealand Wine Fair Sa N Francisco / May 16 2013

New Zealand Wine Fair SA N FRANCISCO 2013 New Zealand Wine Fair SA N FRANCISCO / MAY 16 2013 CONTENTS 2 New Zealand Wine Regions New Zealand Winegrowers is delighted to welcome you to 3 New Zealand Wine – A Land Like No Other the New Zealand Wine Fair: San Francisco 2013. 4 What Does ‘Sustainable’ Mean For New Zealand Wine? 5 Production & Export Overview The annual program of marketing and events is conducted 6 Key Varieties by New Zealand Winegrowers in New Zealand and export 7 Varietal & Regional Guide markets. PARTICIPATING WINERIES When you choose New Zealand wine, you can be confident 10 Allan Scott Family Winemakers you have selected a premium, quality product from a 11 Babich Wines beautiful, sophisticated, environmentally conscious land, 12 Coopers Creek Vineyard where the temperate maritime climate, regional diversity 13 Hunter’s Wines and innovative industry techniques encourage highly 14 Jules Taylor Wines distinctive wine styles, appropriate for any occasion. 15 Man O’ War Vineyards 16 Marisco Vineyards For further information on New Zealand wine and to find 17 Matahiwi Estate SEEKING DISTRIBUTION out about the latest developments in the New Zealand wine 18 Matua Valley Wines industry contact: 18 Mondillo Vineyards SEEKING DISTRIBUTION 19 Mt Beautiful Wines 20 Mt Difficulty Wines David Strada 20 Selaks Marketing Manager – USA 21 Mud House Wines Based in San Francisco 22 Nautilus Estate E: [email protected] 23 Pacific Prime Wines – USA (Carrick Wines, Forrest Wines, Lake Chalice Wines, Maimai Vineyards, Seifried Estate) Ranit Librach 24 Pernod Ricard New Zealand (Brancott Estate, Stoneleigh) Promotions Manager – USA 25 Rockburn Wines Based in New York 26 Runnymede Estate E: [email protected] 27 Sacred Hill Vineyards Ltd. -

New Zealand Earthquake: First Relief Trucks Sent to Kaikoura As Road Opens | World News | the Guardian

10/19/2018 New Zealand earthquake: first relief trucks sent to Kaikoura as road opens | World news | The Guardian New Zealand earthquake: first relief trucks sent to Kaikoura as road opens Army convoy brings supplies for stricken South Island town, while navy ship berths in Christchurch carrying hundreds of evacuees Eleanor Ainge Roy in Dunedin Wed 16 Nov 2016 22.38 EST A road has been cleared to the seaside town of Kaikoura on New Zealand’s east coast four days after it was cut off by a magnitude 7.8 quake that devastated the North Canterbury region of the South Island. The inland road to Kaikoura was opened on Thursday morning, but only for trucks and four- wheel drive vehicles as it remained unstable and badly damaged. A convoy of 27 army vehicles loaded with relief supplies was immediately sent to the town. Gale-force winds and heavy downpours in quake-stricken areas continued to slow the pace of relief efforts, although the majority of the 1,200 tourists stranded in Kaikoura had been evacuated by sea and air. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/17/new-zealand-earthquake-first-relief-trucks-sent-to-kaikoura-as-road-opens 1/3 10/19/2018 New Zealand earthquake: first relief trucks sent to Kaikoura as road opens | World news | The Guardian Nearly 500 evacuees came into Christchurch early on Wednesday morning on the HMNZS Canterbury and were put up in empty student dormitories, where they were offered cooked breakfasts and hot showers after arriving at 5am. Police in Marlborough were using a military Iroquois helicopter to begin checking on isolated high-country farms from the Clarence river to the upper Awatere valley, delivering emergency food and medical supplies to farmers who had gone without assistance since the quake early on Monday. -

Letter Template

ATTACHMENT 5 Geological Assessment (Tonkin & Taylor) Job No: 1007709 10 January 2019 McConnell Property PO Box 614 Auckland 1140 Attention: Matt Anderson Dear Matt Orakei ONF Assessment 1- 3 Purewa Rd, Meadowbank Introduction McConnell Property is proposing to undertake the development of a multi-story apartment building at 1 - 3 Purewa Road, Meadowbank. The property is located within an area covered by the Outstanding Natural Feature (ONF) overlay of the Auckland Unitary Plan. The overlay relates to the Orakei Basin volcano located to the west of the property. The ONF overlay requires consent for the earthworks and the proposed built form associated with the development of the site. McConnell Property has commissioned Tonkin & Taylor Ltd (T+T) to provide a geological assessment of the property with respect to both the ONF overlay and the geological characteristics of the property. The purpose of the assessment is to place the property in context of the significant geological features identified by the ONF overlay, and to assess the geological effects of the proposed development. Proposed Development The proposal (as shown in the architectural drawings appended to the application) is to remove the existing houses and much of the vegetation from the site, and to develop the site with a new four- storey residential apartment building with a single-level basement for parking. The development will involve excavation of the site, which will require cuts of up to approximately 6m below existing ground level (bgl). The cut depths vary across the site, resulting in the average cut depth being less than 6m bgl. Site Description The site is located at the end of the eastern arm of the ridgeline that encloses the Orakei Basin (Figure 1). -

Your Cruise Natural Treasures of New-Zealand

Natural treasures of New-Zealand From 1/7/2022 From Dunedin Ship: LE LAPEROUSE to 1/18/2022 to Auckland On this cruise, PONANT invites you to discover New Zealand, a unique destination with a multitude of natural treasures. Set sail aboard Le Lapérouse for a 12-day cruise from Dunedin to Auckland. Departing from Dunedin, also called the Edinburgh of New Zealand, Le Lapérouse will cruise to the heart of Fiordland National Park, which is an integral part of Te Wahipounamu, UNESCOa World Heritage area with landscapes shaped by successive glaciations. You will discoverDusky Sound, Doubtful Sound and the well-known Milford Sound − three fiords bordered by majestic cliffs. The Banks Peninsula will reveal wonderful landscapes of lush hills and rugged coasts during your call in thebay of Akaroa, an ancient, flooded volcano crater. In Picton, you will discover the Marlborough region, famous for its vineyards and its submerged valleys. You will also sail to Wellington, the capital of New Zealand. This ancient site of the Maori people, as demonstrated by the Te Papa Tongarewa Museum, perfectly combines local traditions and bustling nightlife. From Tauranga, you can discover the many treasuresRotorua of : volcanoes, hot springs, geysers, rivers and gorges, and lakes that range in colour from deep blue to orange-tinged. Then your ship will cruise towards Auckland, your port of disembarkation. Surrounded by the blue waters of the Pacific, the twin islands of New Zealand are the promise of an incredible mosaic of contrasting panoramas. The information in this document is valid as of 9/24/2021 Natural treasures of New-Zealand YOUR STOPOVERS : DUNEDIN Embarkation 1/7/2022 from 4:00 PM to 5:00 PM Departure 1/7/2022 at 6:00 PM Dunedin is New Zealand's oldest city and is often referred to as the Edinburgh of New Zealand. -

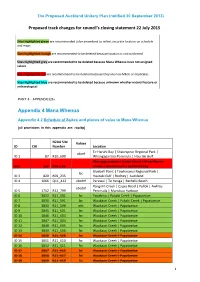

Appendix 4 Mana Whenua

The Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan (notified 30 September 2013) Proposed track changes for council’s closing statement 22 July 2015 Sites highlighted green are recommended to be amendend to reflect accurate location on schedule and maps Sites highlighted orange are recommended to be deleted because location is not confirmed Sites highlighted grey are recommended to be deleted because Mana Whenua have not assigned values Sites highlighted red are recommended to be deleted because they are non-Māori or duplicates Sites highlighted blue are recommended to be deleted because unknown whether natural feature or archaeological PART 5 • APPENDICES» Appendix 4 Mana Whenua Appendix 4.2 Schedule of Ssites and places of value to Mana Whenua [all provisions in this appendix are: rcp/dp] NZAA Site Values ID CHI Number Location Te Haruhi Bay | Shakespear Regional Park | abcef ID 1 87 R10_699 Whangaparaoa Peninsula | Hauraki Gulf. Whangaparapara | Aotea Island | Great Barrier ID 2 502 S09_116 Island. | Hauraki Gulf | Auckland City Bluebell Point | Tawharanui Regional Park | bc ID 3 829 R09_235 Hauraki Gulf | Rodney | Auckland ID 4 1066 Q11_412 abcdef Parawai | Te Henga | Bethells Beach Rangiriri Creek | Capes Road | Pollok | Awhitu abcdef ID 5 1752 R12_799 Peninsula | Manukau Harbour ID 6 3832 R11_581 bc Papahinu | Pukaki Creek | Papatoetoe ID 7 3835 R11_591 bc Waokauri Creek | Pukaki Creek | Papatoetoe ID 8 3843 R11_599 abc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe ID 9 3845 R11_601 bc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe ID 10 3846 R11_603 bc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe -

Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule

Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule [rcp/dp] Introduction The factors in B4.2.2(4) have been used to determine the features included in Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule, and will be used to assess proposed future additions to the schedule. ID Name Location Site type Description Unitary Plan criteria 2 Algies Beach Algies Bay E This site is one of the a, b, g melange best examples of an exposure of the contact between Northland Allocthon and Miocene Waitemata Group rocks. 3 Ambury Road Mangere F A complex 140m long a, b, c, lava cave Bridge lava cave with two d, g, i branches and many well- preserved flow features. Part of the cave contains unusual lava stalagmites with corresponding stalactites above. 4 Anawhata Waitākere A This locality includes a a, c, e, gorge and combination of g, i, l beach unmodified landforms, produced by the dynamic geomorphic processes of the Waitakere coast. Anawhata Beach is an exposed sandy beach, accumulated between dramatic rocky headlands. Inland from the beach, the Anawhata Stream has incised a deep gorge into the surrounding conglomerate rock. 5 Anawhata Waitākere E A well-exposed, and a, b, g, l intrusion unusual mushroom-shaped andesite intrusion in sea cliffs in a small embayment around rocks at the north side of Anawhata Beach. 6 Arataki Titirangi E The best and most easily a, c, l volcanic accessible exposure in breccia and the eastern Waitākere sandstone Ranges illustrating the interfingering nature of Auckland Unitary Plan Operative in part 1 Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule the coarse volcanic breccias from the Waitākere Volcano with the volcanic-poor Waitematā Basin sandstone and siltstones. -

And Taewa Māori (Solanum Tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Traditional Knowledge Systems and Crops: Case Studies on the Introduction of Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and Taewa Māori (Solanum tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of AgriScience in Horticultural Science at Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand Rodrigo Estrada de la Cerda 2015 Kūmara and Taewa Māori, Ōhakea, New Zealand i Abstract Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and taewa Māori, or Māori potato (Solanum tuberosum), are arguably the most important Māori traditional crops. Over many centuries, Māori have developed a very intimate relationship to kūmara, and later with taewa, in order to ensure the survival of their people. There are extensive examples of traditional knowledge aligned to kūmara and taewa that strengthen the relationship to the people and acknowledge that relationship as central to the human and crop dispersal from different locations, eventually to Aotearoa / New Zealand. This project looked at the diverse knowledge systems that exist relative to the relationship of Māori to these two food crops; kūmara and taewa. A mixed methodology was applied and information gained from diverse sources including scientific publications, literature in Spanish and English, and Andean, Pacific and Māori traditional knowledge. The evidence on the introduction of kūmara to Aotearoa/New Zealand by Māori is indisputable. Mātauranga Māori confirms the association of kūmara as important cargo for the tribes involved, even detailing the purpose for some of the voyages. -

Hidden Eruptions

HIDDEN ERUPTIONS The Search for AUCKLAND’S VOLCANIC PAST FACT SHEET 02 Fun volcanic facts from the DEtermining VOlcanic Risk in Auckland (DEVORA) Project The Auckland region has a long history of being affected by volcanic eruptions. The region has experienced at least 53 eruptions from the Auckland Volcanic Field (AVF) in the past 200,000 years, and it has been covered by ash from central North Island volcanoes at least 300 times during that period. To determine exactly how often the Auckland region has been affected by eruptions, scientists study ash layers that have been preserved in lake beds. They now think that ash has How can we tell where fallen on Auckland at least once every 600 years! ash layers come from? Scientists have drilled 7 lakes and dried-up lakes looking for ash: Colour /Te Kopua Kai a Hiku, Panmure Basin A white layer = Ash from a larger, more , Pukaki Lagoon, What is volcanic ash? Lake Pupuke /Whakamuhu, distant volcano (e.g. Taupo). Ōrākei Basin, Glover Park When volcanoes erupt, they eject small fragments /Te Hopua a Rangi, and Gloucester Park A black layer = Ash from a smaller, local of broken rock and lava into the air. This material /Te Kopua o Matakerepō. Auckland volcano (e.g. Mt. Wellington). is called tephra. Tephra less than 2mm in size is Onepoto Basin called ash. Ash is so small and light that it is easily picked up and carried by the wind. Ash can travel Location in the core hundreds of kilometres before settling out of the Some large-scale volcanic eruptions are ash cloud and falling to the ground. -

Nzbotsoc No 41 Sept 1995

NEW ZEALAND BOTANICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NUMBER 41 SEPTEMBER 1995 NEW ZEALAND BOTANICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NUMBER 41 SEPTEMBER 1995 CONTENTS News New Zealand Botanical Society News From the Committee . 3 Call for nominations 3 Regional Botanical Society News Manawatu Botanical Society 3 Nelson Botanical Society 5 Waikato Botanical Society 6 Wellington Botanical Society 7 Notes and Reports Plant Records Urtica linearifolia (Hook. f.) Cockayne - a new northern limit 7 Pittosporum obcordatum in the Catlins Forest Park . .8 Research Reports A story about grass skirts 9 Some observations on cold damage to native plants on Hinewai Reserve, Banks Peninsula 11 Comment Plant succession and the problem of orchid conservation . ... 15 Biography/Bibliography Ellen Blackwell, the mystery lady of New Zealand botany, and "Plants of New Zealand" . 15 Biographical Notes (19): William Alexander Thomson (1876-1950) .. 18 Sex and Elingamita: A Cautionary Tale 20 Publications Journals received 22 Threatened plant poster 22 Desiderata Nothofagus collection at Royal Botanic Garden, Wakehurst Place 23 Nikau seed and seedlings wanted 23 Book Review Index Kewensis on CD-ROM 23 Cover illustration Elingamita johnsonii a small tree up to 4 m tall belonging to the Myrsinaceae is confined to two islands of the Three Kings group (see article page 20). The cover illustration is one of 25 illustrations by Sabrina Malcolm featured on the just published Manaaki Whenua Press Threatened Plants poster (see page 22). New Zealand Botanical Society President: Dr Eric Godley Secretary/Treasurer: Anthony Wright Committee: Sarah Beadel, Colin Webb, Carol West, Beverley Clarkson, Bruce Clarkson Address: C/- Auckland Institute & Museum Private Bag 92018 AUCKLAND Subscriptions The 1995 ordinary and institutional subs are $14 (reduced to $10 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). -

Auckland Plan Targets: Monitoring Report 2015 with DATA for the SOUTHERN INITIATIVE AREA

Auckland plan targets: monitoring report 2015 WITH DATA FOR THE SOUTHERN INITIATIVE AREA Auckland Plan Targets: Monitoring Report 2015 With Data for the Southern Initiative Area March 2016 Technical Report 2016/007 Auckland Council Technical Report 2016/007 ISSN 2230-4525 (Print) ISSN 2230-4533 (Online) ISBN 978-0-9941350-0-1 (Print) ISBN 978-0-9941350-1-8 (PDF) This report has been peer reviewed by the Peer Review Panel. Submitted for review on 26 February 2016 Review completed on 18 March 2016 Reviewed by one reviewer. Approved for Auckland Council publication by: Name: Dr Lucy Baragwanath Position: Manager, Research and Evaluation Unit Date: 18 March 2016 Recommended citation Wilson, R., Reid, A and Bishop, C (2016). Auckland Plan targets: monitoring report 2015 with data for the Southern Initiative area. Auckland Council technical report, TR2016/007 Note This technical report updates and replaces Auckland Council technical report TR2015/030 Auckland Plan Targets: monitoring report 2015 which does not contain data for the Southern Initiative area. © 2016 Auckland Council This publication is provided strictly subject to Auckland Council's copyright and other intellectual property rights (if any) in the publication. Users of the publication may only access, reproduce and use the publication, in a secure digital medium or hard copy, for responsible genuine non-commercial purposes relating to personal, public service or educational purposes, provided that the publication is only ever accurately reproduced and proper attribution of its source, publication date and authorship is attached to any use or reproduction. This publication must not be used in any way for any commercial purpose without the prior written consent of Auckland Council. -

Attachment Manurewa Open Space Netw

Manurewa Open Space Network Plan August 2018 1 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Purpose of the network plan ................................................................................................................................ 7 1.2 Strategic context .................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.3 Manurewa Local Board area ............................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Current State ..................................................................................................................................................... 12 Treasure ............................................................................................................................................................. 12 Enjoy ................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Connect .............................................................................................................................................................. 22