“The Curious Mixture of Signs” That Is Hieroglyphics*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

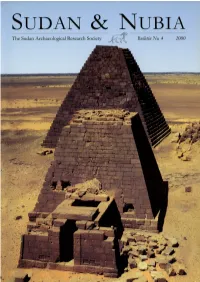

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Relations in the Humanities Between Germany and Egypt

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg HANS ROBERT ROEMER Relations in the humanities between Germany and Egypt On the occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907 – 1982) Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Ägypten, Dauer und Wandel : Symposium anlässlich d. 75jährigen Bestehens d. Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Kairo. Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern, 1985, S.1 - 6 Relations in the Humanities between Germany and Egypt On the Occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907-1982) by HANS ROBERT ROEMER I The nucleus of the Institute whose jubilee we are celebrating today was established in Cairo in 1907 as »The Imperial German Institute for Egyptian Archaeology«. This was the result of a proposal presented by the Berlin Egyptologist Adolf Erman on behalf of the commission for the Egyptian Dictionary, formed by the German Academies of Sciences. This establishment had its antecedents in the 19th century, whose achievements were not only incomparable developments in the natural sciences, but also an unprecedented rise in the Humanities, a field in which German Egyptologists had contributed a substantial share. It is hence no exaggeration to consider the Institute the crowning and the climax of the excavation and research work accomplished earlier in this country. As a background, the German-Egyptian relations in the field of Humanities had already had a flourishing tradition. They had been inaugurated by Karl Richard Lepsius (1810-84) with a unique scientific work, completed in 1859, namely the publication of his huge twelve-volume book »Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Nubien« (»Monuments from Egypt and Nubia«), devoted to the results of a four-year expedition that he had undertaken. -

The Writing of the Birds. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Before and After the Founding of Alexandria1

The Writing of the Birds. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Before and After the Founding of Alexandria1 Stephen Quirke, UCL Institute of Archaeology Abstract As Okasha El Daly has highlighted, qalam al-Tuyur “script of the birds” is one of the Arabic names used by the writers of the Ayyubid period and earlier to describe ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. The name may reflect the regular choice of Nile birds as signs for several consonants in the Ancient Egyptian language, such as the owl for “m”. However, the term also finds an ancestor in a rarer practice of hieroglyph users centuries earlier. From the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods and before, cursive manuscripts have preserved a list of sounds in the ancient Egyptian language, in the sequence used for the alphabet in South Arabian scripts known in Arabia before Arabic. The first “letter” in the hieroglyphic version is the ibis, the bird of Thoth, that is, of knowledge, wisdom and writing. In this paper I consider the research of recent decades into the Arabian connections to this “bird alphabet”. 1. Egyptological sources beyond traditional Egyptology Whether in our first year at school, or in our last year of university teaching, as life-long learners we engage with both empirical details, and frameworks of thought. In the history of ideas, we might borrow the names “philology” for the attentive study of the details, and “philosophy” for traditions of theoretical thinking.2As the classical Arabic tradition demonstrates in the wide scope of its enquiry and of its output, the quest for knowledge must combine both directions of research in order to move forward. -

"Excavating the Old Kingdom. the Giza Necropolis and Other Mastaba

EGYPTIAN ART IN THE AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK This volume has been published in "lIljunction All ri~llIs r,'slTv"d, N"l'art 01 Ihis l'ul>li,';\II"n Tl'.ul,,,,,i,,,,, f... "u the I'r,'u,'h by .I;\nl<" 1'. AlIl'll with the exhibition «Egyptian Art in the Age of may be reproduced llI' ',",lIlsmilt"" by any '"l';\nS, of "'''Iys I>y Nadine (:I",rpion allll,kan-Philippe the Pyramids," organized by The Metropolitan electronic or mechanical, induding phorocopyin~, I,auer; by .Iohu Md )on;\ld of essays by Nicolas Museum of Art, New York; the Reunion des recording, or information retrieval system, with Grima I, Audran I."brousse, .lean I.eclam, and musees nationaux, Paris; and the Royal Ontario out permission from the publishers. Christiane Ziegler; hy .lane Marie Todd and Museum, Toronto, and held at the Gaieries Catharine H. Roehrig of entries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, from April 6 John P. O'Neill, Editor in Chief to July 12, 1999; The Metropolitan Museum of Carol Fuerstein, Editor, with the assistance of Maps adapted by Emsworth Design, Inc., from Art, New York, from September 16,1999, to Ellyn Childs Allison, Margaret Donovan, and Ziegler 1997a, pp. 18, 19 January 9, 2000; and the Royal Ontario Museum, Kathleen Howard Toronto, from February 13 to May 22, 2000. Patrick Seymour, Designer, after an original con Jacket/cover illustration: Detail, cat. no. 67, cept by Bruce Campbell King Menkaure and a Queen Gwen Roginsky and Hsiao-ning Tu, Production Frontispiece: Detail, cat. -

Bulletin De L'institut Français D'archéologie Orientale

MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE BULLETIN DE L’INSTITUT FRANÇAIS D’ARCHÉOLOGIE ORIENTALE en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne BIFAO 114 (2014), p. 455-518 Nico Staring The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara Conditions d’utilisation L’utilisation du contenu de ce site est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Toute autre utilisation du site et de son contenu est soumise à une autorisation préalable de l’éditeur (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). Le copyright est conservé par l’éditeur (Ifao). Conditions of Use You may use content in this website only for your personal, noncommercial use. Any further use of this website and its content is forbidden, unless you have obtained prior permission from the publisher (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). The copyright is retained by the publisher (Ifao). Dernières publications 9782724708288 BIFAO 121 9782724708424 Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l'étranger (BAEFE) 9782724707878 Questionner le sphinx Philippe Collombert (éd.), Laurent Coulon (éd.), Ivan Guermeur (éd.), Christophe Thiers (éd.) 9782724708295 Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 30 Sylvie Marchand (éd.) 9782724708356 Dendara. La Porte d'Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724707953 Dendara. La Porte d’Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724708394 Dendara. La Porte d'Hathor Sylvie Cauville 9782724708011 MIDEO 36 Emmanuel Pisani (éd.), Dennis Halft (éd.) © Institut français d’archéologie orientale - Le Caire Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 1 / 1 The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara nico staring* Introduction In 2005 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acquired a photograph taken by French Egyptologist Théodule Devéria (fig. -

Archaeology on Egypt's Edge

doi: 10.2143/AWE.12.0.2994445 AWE 12 (2013) 117-156 ARCHAEOLOGY ON EGYPT’S EDGE: ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN THE DAKHLEH OASIS, 1819–1977 ANNA LUCILLE BOOZER Abstract This article provides the first substantial survey of early archaeological research in Egypt’s Dakhleh Oasis. In addition to providing a much-needed survey of research, this study embeds Dakhleh’s regional research history within a broader archaeological research framework. Moreover, it explores the impact of contemporaneous historical events in Egypt and Europe upon the development of archaeology in Dakhleh. This contextualised approach allows us to trace influences upon past research trends and their impacts upon current research and approaches, as well as suggest directions for future research. Introduction This article explores the early archaeological research in Egypt’s Dakhleh Oasis within the framework of broad archaeological trends and contemporaneous his- torical events. Egypt’s Western Desert offered a more extreme research environ- ment than the Nile valley and, as a result, experienced a research trajectory different from and significantly later than most of Egyptian archaeology. In more recent years, the archaeology along Egypt’s fringes has provided a significant contribution to our understanding of post-Pharaonic Egypt and it is important to understand how this research developed.1 The present work recounts the his- tory of research in Egypt’s Western Desert in order to embed the regional research history of the Dakhleh Oasis within broader trends in Egyptology, archaeology and world historical events in Egypt and Europe (Figs. 1–2).2 1 In particular, the western oases have dramatically reshaped our sense of the post-Pharaonic occupation of Egypt as well as the ways in which the Roman empire interfaced with local popula- tions. -

Key Words Ancient Egypt, Enlightenment, Dictator Rule, Colonialism, Patriotism, Individualism, Middle-Ages Arab Nationalism

CONTEMPORARY LITERARY REVIEW INDIA – The journal that brings articulate writings for articulate readers. CLRI ISSN 2250-3366 eISSN 2394-6075 Western-Made Source of Naguib Mahfouz’s Pharaonic Novels by Mohamed Kamel Abdel-Daem Abstract This paper argues that the efforts and discoveries in Egyptology made by European archaeologists and historians are the main references that helped the modern Egyptian people and writers learn about the history of ancient Egypt. Naguib Mahfouz’s three novels about ancient Egypt – written in the late 1930s when Egypt was under the British occupation and the Turkish rule – unconsciously conveyed postcolonial ideas to the colonized people, i.e, surrender to Fate (the colonizer’s and dictator’s reality) (Khufu’s Wisdom), irrelevance of democratic rule, lack of centralized regime leads to conflict between two domineering authorities – religious and military (Rhadopis of Nubia), and political relief from contemporary oppression springing from nostalgic pride for forcing the invaders out (Thebes at War). The three novels foster enlightenment principles of Egyptian patriotism (rather than Middle-Ages Arab) nationalism, and this helped implement the European colonizer’s strategy: ‘diaírei kaì basíleue ’. Key words ancient Egypt, enlightenment, dictator rule, colonialism, patriotism, individualism, Middle-Ages Arab nationalism. Introduction Egypt had been one of the places that witnessed the birth of human civilization. Pharaonic culture had come to existence thousands of years before, and lasted thousands of years longer than, Western civilization. But how did we know about, and how did the modern Egyptians learn about, the history of their ancient forefathers? The answer would certainly be: “from history sourcebooks”; and these books are mainly based on information in ancient parchments, as well as paintings on ancient Egyptian monuments. -

Egypt in the Old Kingdom the British Museum the Pyramids and Tombs

Egypt in the Old Kingdom The British Museum The pyramids and tombs of Egypt's Old Kingdom (Third to Sixth Dynasties, about 2686- 2181 BC), with their magnificent reliefs, paintings, statues and stelae, have often been seen as the epitome of the whole of ancient Egypt. Indeed, if the Early Dynastic period was the formative period in which the bases of Egyptian civilization were firmly established, the Old Kingdom was when it came of age. From the Fourth Dynasty, the administration of the country was highly organised, controlled by civil servants from the royal residence at Memphis, where the king was supreme. The efficiency of the administration is no better exemplified than in the building of the pyramids: it is estimated that the Great Pyramid when complete contained about 2,300,000 blocks of stone of an average weight of 2½ tons, all of which had to be transported from quarry to site. This tour features objects from the period in the British Museum's collection, including remains of the fabric of the early royal pyramids, architectural elements and sculpture from the tombs of the officials that ran the country and a papyrus from one of the most important adminstrative archives of the period. Source URL: http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/online_tours/egypt/egypt_in_the_old_kingdom/egypt_in_the_old_kingdom.aspx Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth201 Saylor.org Reposted with permission for educational use by the British Museum. Page 1 of 14 Faience tile from the Step Pyramid of Djoser While brick remained the basic building material of structures for living in, whether palaces or the houses of the ordinary people, stone was gradually introduced for temples and the tombs of royalty and the élite. -

{PDF} Ancient People and Places Series Egyptians 2Nd Edition Pdf

ANCIENT PEOPLE AND PLACES SERIES EGYPTIANS 2ND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cyril Aldred | 9780500280362 | | | | | Ancient People and Places Series Egyptians 2nd edition PDF Book Under Antoninus Pius oppressive taxation led to a revolt in , of the native Egyptians , which was suppressed only after several years of fighting. She lost it later when the Roman emperor, Aurelian , severed amicable relations between the two countries and retook Egypt in Built for Khufu or Cheops, in Greek , who ruled from to B. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. The 22nd dynasty began around B. The defenders surrender. Egypt nevertheless continued to be an important economic center for the Empire supplying much of its agriculture and manufacturing needs as well as continuing to be an important center of scholarship. Tulunid dynasty. Others credit his elite corps of bodyguards. Ramesses Ten Commandments is another matter. Some graffiti. Middle Kingdom. North America. In a competing cosmology, pharaohs are the living incarnation of Horus, the son of Isis. Whatever the into Egypt and its cities. First Edition; First Printing. Latin, never well established in Egypt, would play a declining role with Greek continuing to be the dominant language of government and scholarship. It represents the concept of eternal life, a state of being that was close to the hearts of the pharaohs, as represented by their tombs and monuments. As well as his conquest of Syria, Thutmose III built a huge number of monuments and put a great deal focus on adding to the temple at Karnak. A huge number of mummified cats were found here, some having been brought great distances to be buried ceremonially. -

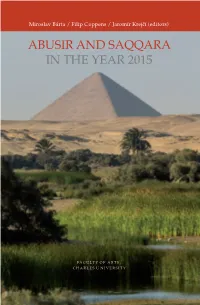

Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2015 Sa Qq a R a Nd Abusir Ye a R 2015 in the a Čí Árt Oppens V B Ír Kre J (Editors) (Editors) Ro M Filip C Filip a J Mirosl A

Miroslav Bárta / Filip Coppens / Jaromír Krejčí (editors) A ABUSIR AND SAQQARA R A IN THE YEAR 2015 QQ SA R 2015 A ND A ABUSIR YE IN THE A ČÍ J ÁRT B OPPENS V C ÍR KRE A (EDITORS) (EDITORS) M RO FILIP FILIP A J MIROSL ISBN 978-80-7308-758-6 FA CULTY OF ARTS, C H A RLES U NIVERSITY AS_vstupy_i_xxiv_ABUSIR 12.1.18 13:34 Stránka i ABUSIR AND SAQQARA IN THE YEAR 2015 AS_vstupy_i_xxiv_ABUSIR 12.1.18 13:34 Stránka ii ii Table Contens The publication was compiled within the framework of the Charles University Progress project Q11 – “Complexity and resilience. Ancient Egyptian civilisation in multidisciplinary and multicultural perspective”. AS_vstupy_i_xxiv_ABUSIR 12.1.18 13:34 Stránka iii Table Contens iii ABUSIR AND SAQQARA IN THE YEAR 2015 Miroslav Bárta – Filip Coppens – Jaromír Krejčí (editors) Faculty of Arts, Charles University Prague 2017 AS_vstupy_i_xxiv_ABUSIR 12.1.18 13:34 Stránka iv iv Table Contens Reviewers Ladislav Bareš, Nigel Strudwick Contributors Katarína Arias Kytnarová, Miroslav Bárta, Edith Bernhauer, Vivienne Gae Callender, Filip Coppens, Jan-Michael Dahms, Vassil Dobrev, Veronika Dulíková, Andres Diego Espinel, Laurel Flentye, Zahi Hawass, Jiří Janák, Peter Jánosi, Lucie Jirásková, Mohamed Ismail Khaled, Evgeniya Kokina, Jaromír Krejčí, Elisabeth Kruck, Hella Küllmer, Audran Labrousse, Renata Landgráfová, Rémi Legros, Radek Mařík, Émilie Martinet, Mohamed Megahed, Diana Míčková, Hassan Nasr el-Dine, Hana Navratilová, Massimiliano Nuzzolo, Martin Odler, Adel Okasha Khafagy, Christian Orsenigo, Robert Parker, Stephane Pasquali, Dominic Perry, Marie Peterková Hlouchová, Patrizia Piacentini, Gabriele Pieke, Maarten J. Raven, Joanne Rowland, Květa Smoláriková, Saleh Soleiman, Anthony J. -

Downloaded 4.0 License

Numen 68 (2021) 157–179 brill.com/nu Negating Seth: Destruction as Vitality Janne Arp-Neumann Institute for Egyptology and Coptic Studies, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany [email protected] Abstract In the past, different points in time have been set as demarcating the beginning of the end of Ancient Egyptian religion. One of these is the start of the so-called “pro- scription” of the god Seth, whose names and images are found damaged in many of their occurrences. In previous studies, this observation was explained as the result of intentional destruction performed during the first millennium bce, and as such as indicative of the decay of Ancient Egyptian religion at this time. However, Seth was from his earliest attestations conceived as a deity ready to perform acts of violence and disruption; under specific circumstances he needed to be banished, but his character was also valued in circumstances requiring violence. This article discusses the prob- lems, fallacies, and arguments of interpreting the intentions behind the destruction of monuments in general and the treatment of Seth in particular. It will be argued that “negating” the image of the “negative” god was not done with malicious intent, but to highlight this god’s role, which was important for the context of the image. It will be proposed that this phenomenon proves that Egyptian religion was still vibrantly alive at that time, not fading away and dying. Keywords Ancient Egyptian religion – Seth (god) – collapse – demise of religion – destruction of names and images – negative god © Janne Arp-Neumann, 2021 | doi:10.1163/15685276-12341619 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-NDDownloaded 4.0 license. -

Open Final Thesis Document.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS AND ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN STUDIES THE INTERNATIONAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EGYPT AND NUBIA EVIDENCED BY THE SEMNA BOUNDARY STELA AND BORDER FORTRESSES KAITLIN MARIE LOVEJOY SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Anthropology and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies with honors in Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Reviewed and approved* by the following: Susan Redford Assistant Teaching Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Thesis Supervisor Erin Hanses Lecturer of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT International relationships are an integral part of understanding human interaction at the global level. These connections occur primarily through politics, economics, territorial expansion, and warfare, parallel to the way that ancient societies often came into contact with one another. Specifically, the international relationship between the ancient civilizations of Egypt and Nubia can be understood under these terms. This project will examine how Egypt interacted with Nubia in reference to the Semna boundary stela of Senwosret III and the border fortresses established along the southern Egyptian-Nubian border. The analyzation of the foreign policy enacted by Senwosret III, how it affected both the Egyptians and the Nubians, and the strategic placement of the fortresses contribute to an overall theme of international affairs in the ancient world. The Semna boundary stela provides the greatest insight into the mind of the Egyptians and, thus, is translated from Middle Egyptian into transliterations and then into English within the body of this text. With extensive research into ancient Egyptian history, politics, and defensive procedures, the significance of Egypt’s relationship with Nubia shapes the pattern of communication between Egypt and most of its foreign neighbors.