Relations in the Humanities Between Germany and Egypt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyberscribe 169-Sept 2009

Cyberscribe 169 1 CyberScribe 169 - September 2009 The CyberScribe did a little math this month and discovered that this issue marks the beginning of his fifteenth year as the writer of this column. He has no idea how many news items have been presented and discussed, but together we have covered a great deal of the Egyptology news during that time. Hopefully you have enjoyed the journey half as much as did the CyberScribe himself. And speaking of longevity, Zahi Hawass confirmed that he is about to retire from his position as head of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. Rumors have been rife for years as to how long he’d remain in this very important post. He has had a much longer tenure than most who held this important position, but at last his task seems to be ending. His times have been marked by controversy, confrontations, grandstanding and posturing…but at the same time he has made very substantial changes in Egyptology, in the monuments and museums of Egypt and in the preservation of Egypt’s heritage. Zahi Hawass has been the consummate showman, drawing immense good will and news attention to Egypt. Here is what he, himself, said about this retirement (read the entire article here, http://tiny.cc/4Q4wq), and understand that the quote below is just part of the interview: “Interviewer: Dr. Hawass, is it true that you plan to retire from the SCA next year? “Zahi Hawass: Yes, by law I have to retire. “Interviewer: What are your plans after leaving office? “Zahi Hawass: I will continue my excavations in the Valley of the Kings, writing books, give lectures everywhere.” This is surprising news, for the retirement of Hawass and the appointment of a successor has been a somewhat taboo subject among Egyptologists. -

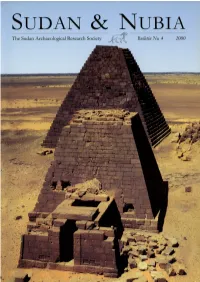

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Egyptian Religion a Handbook

A HANDBOOK OF EGYPTIAN RELIGION A HANDBOOK OF EGYPTIAN RELIGION BY ADOLF ERMAN WITH 130 ILLUSTRATIONS Published in tile original German edition as r handbook, by the Ge:r*rm/?'~?~~ltunf of the Berlin Imperial Morcums TRANSLATED BY A. S. GRIFFITH LONDON ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & CO. LTD. '907 Itic~mnoCLAY B 80~8,L~~II'ED BRIIO 6Tllll&I "ILL, E.C., AY" DUN,I*Y, RUFIOLP. ; ,, . ,ill . I., . 1 / / ., l I. - ' PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION THEvolume here translated appeared originally in 1904 as one of the excellent series of handbooks which, in addition to descriptive catalogues, are ~rovidedby the Berlin Museums for the guida,nce of visitors to their great collections. The haud- book of the Egyptian Religion seemed cspecially worthy of a wide circulation. It is a survey by the founder of the modern school of Egyptology in Germany, of perhaps tile most interest- ing of all the departments of this subject. The Egyptian religion appeals to some because of its endless variety of form, and the many phases of superstition and belief that it represents ; to others because of its early recognition of a high moral principle, its elaborate conceptions of a life aftcr death, and its connection with the development of Christianity; to others again no doubt because it explains pretty things dear to the collector of antiquities, and familiar objects in museums. Professor Erman is the first to present the Egyptian religion in historical perspective; and it is surely a merit in his worlc that out of his profound knowledge of the Egyptian texts, he permits them to tell their own tale almost in their own words, either by extracts or by summaries. -

The Writing of the Birds. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Before and After the Founding of Alexandria1

The Writing of the Birds. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Before and After the Founding of Alexandria1 Stephen Quirke, UCL Institute of Archaeology Abstract As Okasha El Daly has highlighted, qalam al-Tuyur “script of the birds” is one of the Arabic names used by the writers of the Ayyubid period and earlier to describe ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. The name may reflect the regular choice of Nile birds as signs for several consonants in the Ancient Egyptian language, such as the owl for “m”. However, the term also finds an ancestor in a rarer practice of hieroglyph users centuries earlier. From the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods and before, cursive manuscripts have preserved a list of sounds in the ancient Egyptian language, in the sequence used for the alphabet in South Arabian scripts known in Arabia before Arabic. The first “letter” in the hieroglyphic version is the ibis, the bird of Thoth, that is, of knowledge, wisdom and writing. In this paper I consider the research of recent decades into the Arabian connections to this “bird alphabet”. 1. Egyptological sources beyond traditional Egyptology Whether in our first year at school, or in our last year of university teaching, as life-long learners we engage with both empirical details, and frameworks of thought. In the history of ideas, we might borrow the names “philology” for the attentive study of the details, and “philosophy” for traditions of theoretical thinking.2As the classical Arabic tradition demonstrates in the wide scope of its enquiry and of its output, the quest for knowledge must combine both directions of research in order to move forward. -

"Excavating the Old Kingdom. the Giza Necropolis and Other Mastaba

EGYPTIAN ART IN THE AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK This volume has been published in "lIljunction All ri~llIs r,'slTv"d, N"l'art 01 Ihis l'ul>li,';\II"n Tl'.ul,,,,,i,,,,, f... "u the I'r,'u,'h by .I;\nl<" 1'. AlIl'll with the exhibition «Egyptian Art in the Age of may be reproduced llI' ',",lIlsmilt"" by any '"l';\nS, of "'''Iys I>y Nadine (:I",rpion allll,kan-Philippe the Pyramids," organized by The Metropolitan electronic or mechanical, induding phorocopyin~, I,auer; by .Iohu Md )on;\ld of essays by Nicolas Museum of Art, New York; the Reunion des recording, or information retrieval system, with Grima I, Audran I."brousse, .lean I.eclam, and musees nationaux, Paris; and the Royal Ontario out permission from the publishers. Christiane Ziegler; hy .lane Marie Todd and Museum, Toronto, and held at the Gaieries Catharine H. Roehrig of entries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, from April 6 John P. O'Neill, Editor in Chief to July 12, 1999; The Metropolitan Museum of Carol Fuerstein, Editor, with the assistance of Maps adapted by Emsworth Design, Inc., from Art, New York, from September 16,1999, to Ellyn Childs Allison, Margaret Donovan, and Ziegler 1997a, pp. 18, 19 January 9, 2000; and the Royal Ontario Museum, Kathleen Howard Toronto, from February 13 to May 22, 2000. Patrick Seymour, Designer, after an original con Jacket/cover illustration: Detail, cat. no. 67, cept by Bruce Campbell King Menkaure and a Queen Gwen Roginsky and Hsiao-ning Tu, Production Frontispiece: Detail, cat. -

Glossing the Past: the Fifth Dynasty Sun Temples, Abu Ghurab and the Satellite Imagery

PES XIX_2017_studied_90-136_PES 14.12.17 9:47 Stránka 110 1 1 0 PES XIX/2017 GLOSSING THE PAST: THE FIFTH DYNASTY SUN TEMPLES Fig. 1 Historical cartography of the Abusir plateau in comparison (from left to right): Lepsius’ map (1849: pl. 32), De Morgan’s map (1897: pl. 11) and the Franco-Egyptian map (EMHR 1978, sheet 21). The circles enclose the two missing Pyramids Lepsius XVI and Lepsius XXVIII Glossing the past: the Fifth Dynasty sun temples, Abu Ghurab and the satellite imagery Massimiliano Nuzzolo – Patrizia Zanfagna On the northernmost foothill of the Abusir plateau, which is usually known as Abu Ghurab, a few hundred meters from the royal necropolis, the Fifth Dynasty pharaohs built some of the most intriguing monuments of ancient Egyptian architecture, the so-called sun temples. So far, however, only two of the six temples known from the textual sources of the time have been identified and systematically excavated, i.e. that of Userkaf and Nyuserre. Four sanctuaries still remain to be discovered. The present paper has thus the aim to shed some light on their possible locations by means of the combined analysis of archaeological evidence, historical cartography and new remote sensing imagery. Over the past two decades, remote sensing techniques have well as the identification of a complex system of commu- been increasingly used in Egyptology for the study and re- nication, dating back to the Old Kingdom, between the construction of the archeological landscape of ancient Red Sea coast and the copper mines of the Wadi Maghara Egypt and the analysis of its topographical and spatial pe- (Mumford – Parcak 2003: 83–116; Parcak 2004a: culiarities. -

Bulletin De L'institut Français D'archéologie Orientale

MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE BULLETIN DE L’INSTITUT FRANÇAIS D’ARCHÉOLOGIE ORIENTALE en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne BIFAO 114 (2014), p. 455-518 Nico Staring The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara Conditions d’utilisation L’utilisation du contenu de ce site est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Toute autre utilisation du site et de son contenu est soumise à une autorisation préalable de l’éditeur (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). Le copyright est conservé par l’éditeur (Ifao). Conditions of Use You may use content in this website only for your personal, noncommercial use. Any further use of this website and its content is forbidden, unless you have obtained prior permission from the publisher (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). The copyright is retained by the publisher (Ifao). Dernières publications 9782724708288 BIFAO 121 9782724708424 Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l'étranger (BAEFE) 9782724707878 Questionner le sphinx Philippe Collombert (éd.), Laurent Coulon (éd.), Ivan Guermeur (éd.), Christophe Thiers (éd.) 9782724708295 Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 30 Sylvie Marchand (éd.) 9782724708356 Dendara. La Porte d'Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724707953 Dendara. La Porte d’Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724708394 Dendara. La Porte d'Hathor Sylvie Cauville 9782724708011 MIDEO 36 Emmanuel Pisani (éd.), Dennis Halft (éd.) © Institut français d’archéologie orientale - Le Caire Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 1 / 1 The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara nico staring* Introduction In 2005 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acquired a photograph taken by French Egyptologist Théodule Devéria (fig. -

Archaeology on Egypt's Edge

doi: 10.2143/AWE.12.0.2994445 AWE 12 (2013) 117-156 ARCHAEOLOGY ON EGYPT’S EDGE: ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN THE DAKHLEH OASIS, 1819–1977 ANNA LUCILLE BOOZER Abstract This article provides the first substantial survey of early archaeological research in Egypt’s Dakhleh Oasis. In addition to providing a much-needed survey of research, this study embeds Dakhleh’s regional research history within a broader archaeological research framework. Moreover, it explores the impact of contemporaneous historical events in Egypt and Europe upon the development of archaeology in Dakhleh. This contextualised approach allows us to trace influences upon past research trends and their impacts upon current research and approaches, as well as suggest directions for future research. Introduction This article explores the early archaeological research in Egypt’s Dakhleh Oasis within the framework of broad archaeological trends and contemporaneous his- torical events. Egypt’s Western Desert offered a more extreme research environ- ment than the Nile valley and, as a result, experienced a research trajectory different from and significantly later than most of Egyptian archaeology. In more recent years, the archaeology along Egypt’s fringes has provided a significant contribution to our understanding of post-Pharaonic Egypt and it is important to understand how this research developed.1 The present work recounts the his- tory of research in Egypt’s Western Desert in order to embed the regional research history of the Dakhleh Oasis within broader trends in Egyptology, archaeology and world historical events in Egypt and Europe (Figs. 1–2).2 1 In particular, the western oases have dramatically reshaped our sense of the post-Pharaonic occupation of Egypt as well as the ways in which the Roman empire interfaced with local popula- tions. -

Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut

iii OCCASIONAL PROCEEDINGS OF THE THEBAN WORKSHOP Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut edited by José M. Galán, Betsy M. Bryan, and Peter F. Dorman Papers from the Theban Workshop 2010 2014 studies in ancient ORientaL civiLizatiOn • numbeR 69 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE of THE UNIVERSITY of CHICAgo chicagO • IllinOis v Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................. vii Program of the Theban Workshop, 2010 Preface, José M. Galán, SCIC, Madrid ........................................................................... viii PAPERS FROM THE THEBAN WORKSHOP, 2010 1. Innovation at the Dawn of the New Kingdom. Peter F. Dorman, American University of Beirut...................................................... 1 2. The Paradigms of Innovation and Their Application to the Early New Kingdom of Egypt. Eberhard Dziobek, Heidelberg and Leverkusen....................................................... 7 3. Worldview and Royal Discourse in the Time of Hatshepsut. Susanne Bickel, University of Basel ............................................................... 21 4. Hatshepsut at Karnak: A Woman under God’s Commands. Luc Gabolde, CNRS (UMR 5140) .................................................................. 33 5. How and Why Did Hatshepsut Invent the Image of Her Royal Power? Dimitri Laboury, University of Liège .............................................................. 49 6. Hatshepsut and cultic Revelries in the new Kingdom. Betsy M. Bryan, The Johns Hopkins -

Key Words Ancient Egypt, Enlightenment, Dictator Rule, Colonialism, Patriotism, Individualism, Middle-Ages Arab Nationalism

CONTEMPORARY LITERARY REVIEW INDIA – The journal that brings articulate writings for articulate readers. CLRI ISSN 2250-3366 eISSN 2394-6075 Western-Made Source of Naguib Mahfouz’s Pharaonic Novels by Mohamed Kamel Abdel-Daem Abstract This paper argues that the efforts and discoveries in Egyptology made by European archaeologists and historians are the main references that helped the modern Egyptian people and writers learn about the history of ancient Egypt. Naguib Mahfouz’s three novels about ancient Egypt – written in the late 1930s when Egypt was under the British occupation and the Turkish rule – unconsciously conveyed postcolonial ideas to the colonized people, i.e, surrender to Fate (the colonizer’s and dictator’s reality) (Khufu’s Wisdom), irrelevance of democratic rule, lack of centralized regime leads to conflict between two domineering authorities – religious and military (Rhadopis of Nubia), and political relief from contemporary oppression springing from nostalgic pride for forcing the invaders out (Thebes at War). The three novels foster enlightenment principles of Egyptian patriotism (rather than Middle-Ages Arab) nationalism, and this helped implement the European colonizer’s strategy: ‘diaírei kaì basíleue ’. Key words ancient Egypt, enlightenment, dictator rule, colonialism, patriotism, individualism, Middle-Ages Arab nationalism. Introduction Egypt had been one of the places that witnessed the birth of human civilization. Pharaonic culture had come to existence thousands of years before, and lasted thousands of years longer than, Western civilization. But how did we know about, and how did the modern Egyptians learn about, the history of their ancient forefathers? The answer would certainly be: “from history sourcebooks”; and these books are mainly based on information in ancient parchments, as well as paintings on ancient Egyptian monuments. -

DIALOGUES with the DEAD Comp

Comp. by: PG0844 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0001734582 Date:13/10/12 Time:13:59:20 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001734582.3D1 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 13/10/2012, SPi DIALOGUES WITH THE DEAD Comp. by: PG0844 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0001734582 Date:13/10/12 Time:13:59:20 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001734582.3D2 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 13/10/2012, SPi Comp. by: PG0844 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0001734582 Date:13/10/12 Time:13:59:20 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001734582.3D3 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 13/10/2012, SPi Dialogues with the Dead Egyptology in British Culture and Religion 1822–1922 DAVID GANGE 1 Comp. by: PG0844 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0001734582 Date:13/10/12 Time:13:59:20 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001734582.3D4 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 13/10/2012, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University press in the UK and in certain other countries # David Gange 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2013 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

Egypt in the Old Kingdom the British Museum the Pyramids and Tombs

Egypt in the Old Kingdom The British Museum The pyramids and tombs of Egypt's Old Kingdom (Third to Sixth Dynasties, about 2686- 2181 BC), with their magnificent reliefs, paintings, statues and stelae, have often been seen as the epitome of the whole of ancient Egypt. Indeed, if the Early Dynastic period was the formative period in which the bases of Egyptian civilization were firmly established, the Old Kingdom was when it came of age. From the Fourth Dynasty, the administration of the country was highly organised, controlled by civil servants from the royal residence at Memphis, where the king was supreme. The efficiency of the administration is no better exemplified than in the building of the pyramids: it is estimated that the Great Pyramid when complete contained about 2,300,000 blocks of stone of an average weight of 2½ tons, all of which had to be transported from quarry to site. This tour features objects from the period in the British Museum's collection, including remains of the fabric of the early royal pyramids, architectural elements and sculpture from the tombs of the officials that ran the country and a papyrus from one of the most important adminstrative archives of the period. Source URL: http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/online_tours/egypt/egypt_in_the_old_kingdom/egypt_in_the_old_kingdom.aspx Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth201 Saylor.org Reposted with permission for educational use by the British Museum. Page 1 of 14 Faience tile from the Step Pyramid of Djoser While brick remained the basic building material of structures for living in, whether palaces or the houses of the ordinary people, stone was gradually introduced for temples and the tombs of royalty and the élite.