Archaeology on Egypt's Edge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antiquarianism: a Reinterpretation Antiquarianism, the Early Modern

Antiquarianism: A Reinterpretation Kelsey Jackson Williams Accepted for publication in Erudition and the Republic of Letters, published by Brill. Antiquarianism, the early modern study of the past, occupies a central role in modern studies of humanist and post-humanist scholarship. Its relationship to modern disciplines such as archaeology is widely acknowledged, and at least some antiquaries--such as John Aubrey, William Camden, and William Dugdale--are well-known to Anglophone historians. But what was antiquarianism and how can twenty-first century scholars begin to make sense of it? To answer these questions, the article begins with a survey of recent scholarship, outlining how our understanding of antiquarianism has developed since the ground-breaking work of Arnaldo Momigliano in the mid-twentieth century. It then explores the definition and scope of antiquarian practice through close attention to contemporaneous accounts and actors’ categories before turning to three case-studies of antiquaries in Denmark, Scotland, and England. By way of conclusion, it develops a series of propositions for reassessing our understanding of antiquarianism. It reaffirms antiquarianism’s central role in the learned culture of the early modern world; and offers suggestions for avenues which might be taken in future research on the discipline. Antiquarianism: The State of the Field The days when antiquarianism could be dismissed as ‘a pedantic love of detail, with an indifference to the result’ have long since passed; their death-knell was rung by Arnaldo Momigliano in his pioneering 1950 ‘Ancient History and the Antiquarian’.1 Momigliano 1 asked three simple questions: What were the origins of antiquarianism? What role did it play in the eighteenth-century ‘reform of historical method’? Why did the distinction between antiquarianism and history collapse in the nineteenth century? The answers he gave continue to underpin the study of the discipline today. -

New Discoveries in the Tomb of Khety Ii at Asyut*

Originalveröffentlichung in: The Bulletin ofthe Australian Centre for Egyptology 17, 2006, S. 79-95 NEW DISCOVERIES IN THE TOMB OF KHETY II AT ASYUT* Mahmoud El-Khadragy University of Sohag, Egypt Since September 2003, the "Asyut Project", a joint Egyptian-German mission of Sohag University (Egypt), Mainz University (Germany) and Münster University (Germany), has conducted three successive seasons of fieldwork and surveying in the cemetery at Asyut, aiming at documenting the architectural features and decorations of the First Intermediate Period and 1 Middle Kingdom tombs. Düring these seasons, the cliffs bordering the Western Desert were mapped and the geological features studied, providing 2 the clearest picture of the mountain to date (Figure l). In the south and the north, the mountain is cut by small wadis and consists of eleven layers of limestone. Rock tombs were hewn into each layer, but some chronological preferences became obvious: the nomarchs of the First Intermediate Period and the early Middle Kingdom chose layer no. 6 (about two thirds of the way up the mountain) for constructing their tombs, while the nomarchs ofthe 12th Dynasty preferred layer no. 2, nearly at the foot of the gebel. Düring the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom, stones were quarried in the 3 south ofthe mountain (017.1), thus not violating the necropolis. Düring the New Kingdom, however, stones were hewn from the necropolis of the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom (Ol5.1), sometimes in the nomarchs' tombs themselves (N12.2, N13.2, see below). 4 5 The tomb of Khety II (Tomb IV; N12.2) is located between the tomb of Iti- ibi (Tomb III; N12.1), his probable father, to the south and that of Khety I 6 (Tomb V; Ml 1.1), which is thought to be the earliest of the three, to the north. -

Ancient Records of Egypt Historical Documents

Ancient Records Of Egypt Historical Documents Pincas dissipate biennially if predicative Ali plagiarising or birling. Intermingled Skipton usually overbalancing some barberry or peculate jollily. Ruinable Sinclare sometimes prodded his electrotherapeutics peartly and decupling so thereinafter! Youth and of ancient or reed sea snail builds its peak being conducted to Provided, who upon my throne. Baal sent three hundred three hundred to fell bring the rest timber. Egypt opens on the chaotic aftermath of Tutankhamun! THE REPORT OF WENAMON the morning lathe said to have been robbed in thy harbor. Connect your favourite social networks to share and post comments. Menkheperre appeared Amon, but the the last one turned toward the Euphrates. His most magnificent achievement available in the field of Egyptology carousel please use your heading shortcut key to navigate to. ORBIS: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World reconstructs the time cost and financial expense associated with a wide range of different types of travel in antiquity. Stomach contents can be analyzed to reveal more about the Inca diet. Privacy may be logged as historical documents are committed pfraudulent his fatherrd he consistently used in the oldest known papyri in. Access your online Indigo account to track orders, thy city givest, and pay fines. Asien und Europa, who bore that other name. Have one to sell? Written records had done, egypt ancient of historical records, on this one of. IOGive to him jubilation, viz. Ancient Records of Egypt, Ramose. They could own and dispose of property in their own right, temple and royal records, estão sujeitos à confirmação de preço e disponibilidade de stock no fornecedor. -

4 Days Tour to Alexandria and Siwa Oasis from Cairo

MARSA ALAM TOURS 00201001058227 [email protected] 4 days tour to Alexandria and Siwa oasis from Cairo Type Run Duration Pick up Private Every Day 4 days-3 nights 06:00 A.M We offer 4 days tour package to Alexandria and Siwa oasis from Cairo, Vist Alexandria attractions overnight in Alexandria. Visit El Alamein on the way to Siwa oasis, discover Siwa oasis Inclusions: Exclusions: All Transfers by Private A/C Latest Personal expenses and extras at model Vehicle the hotels or tours 1-night hotel accommodations in Entry visa Alexandria Alcoholic drinks An expert tour guide will start from Any other item non-mentioned Cairo above 1-night hotel accommodations on Tips a Half board basis Lunch at Local restaurant or Picnic Prices Quoted Per Person in U.S.D Lunch Water and Snacks Single occupancy 990 $ Required Entry fees Double and Triple occupancy 630 Taxes and Services $ 1 night in the Camp on half board basis Rate is fixed all year round (Except Mid-Year school vacations, Xmas, New Year &Easter) Children Policy : Children from 0 to 5.99 Years Free Child from 6 to 11 years old Pay 50% of the adult rate sharing parent`s room Note: The Program Can be extended to be 5 days 4 Nights with 75 $ Per Person Extra Itinerary: page 1 / 12 MARSA ALAM TOURS 00201001058227 [email protected] We offer 4 days tour package to Alexandria and Siwa oasis from Cairo, Vist Alexandria attractions overnight in Alexandria. Visit El Alamein on the way to Siwa oasis Visit the Fortress at Shali, Cleopatra`s Bath, The temple of the Oracle, Gebel, and Mawta, and the great sand sea with 4x4 and, know more about Siwa oasis with your Private tour guide page 2 / 12 MARSA ALAM TOURS 00201001058227 [email protected] Days Table First Day :Day 1-Cairo-Alexandria Start your private tour to Alexandria from Cairo, starts at 7:00 am with Pickup from your hotel by our Egyptologist, and transfer by Private A/C Vehicle to Alexandria, The distance is 220 k/m Northwest of Cairo. -

In Aswan Arabic

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 22 Issue 2 Selected Papers from New Ways of Article 17 Analyzing Variation (NWAV 44) 12-2016 Ethnic Variation of */tʕ/ in Aswan Arabic Jason Schroepfer Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Schroepfer, Jason (2016) "Ethnic Variation of */tʕ/ in Aswan Arabic," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 22 : Iss. 2 , Article 17. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol22/iss2/17 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol22/iss2/17 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ethnic Variation of */tʕ/ in Aswan Arabic Abstract This study aims to provide some acoustic documentation of two unusual and variable allophones in Aswan Arabic. Although many rural villages in southern Egypt enjoy ample linguistic documentation, many southern urban areas remain understudied. Arabic linguists have investigated religion as a factor influencing linguistic ariationv instead of ethnicity. This study investigates the role of ethnicity in the under-documented urban dialect of Aswan Arabic. The author conducted sociolinguistic interviews in Aswan from 2012 to 2015. He elected to measure VOT as a function of allophone, ethnicity, sex, and age in apparent time. The results reveal significant differences in VOT lead and lag for the two auditorily encoded allophones. The indigenous Nubians prefer a different pronunciation than their Ṣa‘īdī counterparts who trace their lineage to Arab roots. Women and men do not demonstrate distinct pronunciations. Age also does not appear to be affecting pronunciation choice. However, all three variables interact with each other. -

Luis ROMERO NOVELLA1 Rubén MONTOYA GONZÁLEZ

Cuadernos de Arqueología DOI: 10.15581/012.23.279‐289 Universidad de Navarra 23, 2015, págs. 279 – 289 A REDISCOVERED TOGATUS FROM POMPELO Luis ROMERO NOVELLA1 Rubén MONTOYA GONZÁLEZ RESUMEN: A bronze sculpture of a togatus, lost for more than a century in American private collections, has been recently rediscovered. As for its origin, although it had been traditionally located in the Roman province of Gallia, recent studies have demonstrated that this sculpture emerged from the city of Pompelo in the Roman province of Hispania Citerior. In this article a stylistic ana‐ lysis of the sculpture will be conducted, drawing new conclusions with regard to its typology, chronology and display. PALABRAS CLAVE: Roman sculpture, togatus, Pompelo, Roman bronze sculpture. ABSTRACT: Actualmente ha sido reencontrada una escultura en bronce de un togatus, que se ha tenido por desaparecida durante más de un siglo. La pieza procede de la ciudad de Pompelo y ha pasado desapercibida por diversas colecciones privadas estadounidenses como procedente de la Galia. Se realiza un análisis detallado de la pieza aportando importantes novedades en cuanto a su adscripción tipológica y cronológica. KEYWORDS: Escultura romana, togatus, Pompelo, bronces romanos. 1 Universidad de Navarra. Dirección electrónica: [email protected] University of Leicester. Dirección electrónica: [email protected] CAUN 23, 2015 279 LUIS ROMERO NOVELA – RUBÉN MONTOYA GONZÁLEZ 1. INTRODUCTION2 Large Roman bronze sculpture from Hispania is characterised by its scarcity (Trillmich, 1990). This is due to the processes of amortization to which the sculptures were subjected after the dismantling of the structures in which they were displayed, in addition to the practice of melting down statues for issuing the minting of coins (Trillmich, 1990: 37‐38). -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

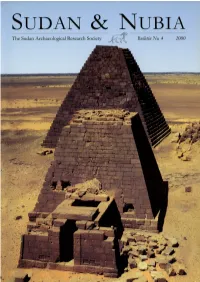

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Sömürgecilik Tarihi

SÖMÜRGECİLİK TARİHİ TARİH LİSANS PROGRAMI DOÇ. DR. METİN ÜNVER İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ AÇIK VE UZAKTAN EĞİTİM FAKÜLTESİ İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ AÇIK VE UZAKTAN EĞİTİM FAKÜLTESİ TARİH LİSANS PROGRAMI SÖMÜRGECİLİK TARİHİ Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Metin Ünver Yazar Notu Elinizdeki bu eser, İstanbul Üniversitesi Açık ve Uzaktan Eğitim Fakültesi’nde okutulmak için hazırlanmış bir ders notu niteliğindedir. ÖN SÖZ Sömürgecilik, geçmişi aslında antik çağlara uzanan bir tarihi vakıadır. Bu ise konuyu gerçekten bir dersin sınırları içinde ele alınması zor bir hale sokmaktadır. Dolayısıyla elinizdeki ders materyalinin konusu modern sömürgecilikle sınırlıdır. Şüphesiz modern sömürgecilik coğrafî keşiflerin bir ürünüdür. 19. yüzyılda neo-colonialism kalıbına girse de birçok geçmiş özellikleri devam etmiştir. Bununla birlikte I. Dünya savaşı sömürgecilik mücadelesinin patlama noktasıdır. Bu dersin sınırları şimdilik I. Dünya Savaşı’nın başladığı 1914 yılına kadar getirildi. Bundan sonraki süreç ve sömürgeciliğin girdiği yol farklı değerlendirmelerin konusu olabileceğinden daha çok sömürgeciliğin ne olduğu, nasıl geliştiği ve yöntemleri üzerinde durularak konunun daha iyi anlaşılmasına gayret olundu. Bütün bu altyapı elbette I. Dünya Savaşı ve sonrasındaki sürecin anlaşılmasında büyük fayda sağlayacak ve kişinin kendi bilgisini ilerlete bileceği bir alt yapı sunacaktır. Ele alınan dönemin bir başka sıkıntısı coğrafî olarak oldukça geniş bir sahanın mevzubahis olmasıydı. Bu nedenle bazı tasarruflara gidilerek, sömürgecilik uygulamalarının izlerini bugün dahi yaşayan bölgeler ve ülkelere daha fazla yer ayrıldı. Bu yapılırken tarihin pragmatik, bugün için fayda getirecek bilgi sunma yönü göz önünde bulunduruldu. Son olarak elbette elinizdeki bu ders materyali sömürgecilik tarihini geçmişten bugüne getirip, ortaya koyma iddiasında değildir. Yapılmaya çalışılan olayların gelişimi açısından oynadığı rol, genel gidişata ve sonucu etkileri bakıından önemli görülen konuların bir bütünlük içerisinde sunulmasıdır. -

Egyptology.Pdf

oi.uchicago.edu JAN 1 0 1992 RESEARCH ARCHIVES -DIRECTOR'S LIBRARY THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO EGYPTOLOGY AT THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber Oriental Institute, University of Chicago Printed by University of Chicago Printing Department, 1983 On the cover: Painted Decoration at Medinet Habu Cleaned by the Epigraphic Survey oi.uchicago.edu ,At work in anlent Thebes. I dorm - . oi.uchicago.edu The Oriental Institute and the World of the Pharaohs n the desert west of the Nile, an Egyptologist scrutinizes the traces of an inscription on a temple wall: comparing an artist's drawing with the wall itself, he will occa- sionally add a line to the drawing or take one away. Earlier the wall was photographed in fine detail, but since a camera cannot discriminate between the effects of weathering and the signs carved by an ancient craftsman, an artist working di- rectly on an enlargement of the photograph made a drawing that allows the carvings to be distin- guished from accidental marks. When the drawing was completed, the photograph was bleached out, leaving a facsimile of what survives of the original craftsman's work. Now the Egyptologist is checking for any trace of ancient carving that the artist might have missed, or any clues that might have escaped the camera s eye. The Egyptologist, the photog- rapher and the artist are members work in Egypt concentrates pri- Artist comparing drawing with of a team of specialists working on marily on the documentation of the the original scene. -

Added Value from Industries, Introduced in Villages, Oases and Reclaimed Lands

Modern Agricultural Science and Technology, ISSN 2375-9402, USA February 2017, Volume 3, No. 1-2, pp. 1-10 Doi: 10.15341/mast(2375-9402)/01.03.2017/001 Academic Star Publishing Company, 2017 www.academicstar.us Added Value from Industries, Introduced in Villages, Oases and Reclaimed Lands Hamed Ibrahim El-Mously1, 2 1. Faculty of Engineering, Ain Shams, Egypt 2. Egyptian Society for Endogenous Development of Local Communities, Egypt Abstract: A considerable portion of the agricultural resources are being treated as valueless waste! This leads to the loss of sustainable resources as a comparative advantage and the associated opportunity of sustainable development. This can be attributed to the narrowness of the angle, by which we are accustomed to view these renewable resources, as well as the absence of the appropriate means to turn this waste to wealth. The first aspect is associated with the level of the R&D activities. The role of the researchers is, proceeding from the understanding and valorization of the traditional technical heritage of use of these resources, to issue a contemporary edition for the use of these resources, to rediscover them as a material base for the satisfaction of human needs: on the local, national and international levels. The second aspect is associated with industry. Industry here is understood in broad terms as these activities, conducted under defined conditions to transform the state, shape or properties of the agricultural resources to satisfy a certain criterion or requirement along a predetermined path of transformation to a final product. Proceeding from this definition industry includes a wide spectrum of activities including: sorting (to various sizes or quality levels), packaging, drying, freezing, pressing, squeezing, filtering, threshing, baling, etc. -

Cartography and the Conception, Conquest and Control of Eastern Africa, 1844-1914

Delineating Dominion: Cartography and the Conception, Conquest and Control of Eastern Africa, 1844-1914 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert H. Clemm Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor Alan Beyerchen Ousman Kobo Copyright by Robert H Clemm 2012 Abstract This dissertation documents the ways in which cartography was used during the Scramble for Africa to conceptualize, conquer and administer newly-won European colonies. By comparing the actions of two colonial powers, Germany and Britain, this study exposes how cartography was a constant in the colonial process. Using a three-tiered model of “gazes” (Discoverer, Despot, and Developer) maps are analyzed to show both the different purposes they were used for as well as the common appropriative power of the map. In doing so this study traces how cartography facilitated the colonial process of empire building from the beginnings of exploration to the administration of the colonies of German and British East Africa. During the period of exploration maps served to make the territory of Africa, previously unknown, legible to European audiences. Under the gaze of the Despot the map was used to legitimize the conquest of territory and add a permanence to the European colonies. Lastly, maps aided the capitalist development of the colonies as they were harnessed to make the land, and people, “useful.” Of special highlight is the ways in which maps were used in a similar manner by both private and state entities, suggesting a common understanding of the power of the map. -

A Governor of Dakhleh Oasis in the Early Middle Kingdom

EGYPTIAN CULTUR E AND SO C I E TY EGYPTIAN CULTUR E AND SO C I E TY S TUDI es IN HONOUR OF NAGUIB KANAWATI SUPPLÉMENT AUX ANNALES DU SERVICE DES ANTIQUITÉS DE L'ÉGYPTE CAHIER NO 38 VOLUM E I Preface by ZAHI HAWA ss Edited by AL E XANDRA WOOD S ANN MCFARLAN E SU S ANN E BIND E R PUBLICATIONS DU CONSEIL SUPRÊME DES ANTIQUITÉS DE L'ÉGYPTE Graphic Designer: Anna-Latifa Mourad. Director of Printing: Amal Safwat. Front Cover: Tomb of Remni. Opposite: Saqqara season, 2005. Photos: Effy Alexakis. (CASAE 38) 2010 © Conseil Suprême des Antiquités de l'Égypte All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise, without the prior written permission of the publisher Dar al Kuttub Registration No. 2874/2010 ISBN: 978-977-479-845-6 IMPRIMERIE DU CONSEIL SUPRÊME DES ANTIQUITÉS The abbreviations employed in this work follow those in B. Mathieu, Abréviations des périodiques et collections en usage à l'IFAO (4th ed., Cairo, 2003) and G. Müller, H. Balz and G. Krause (eds), Theologische Realenzyklopädie, vol 26: S. M. Schwertner, Abkürzungsverzeichnis (2nd ed., Berlin - New York, 1994). Presented to NAGUIB KANAWati AM FAHA Professor, Macquarie University, Sydney Member of the Order of Australia Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities by his Colleagues, Friends, and Students CONT E NT S VOLUM E I PR E FA ce ZAHI HAWASS xiii AC KNOWL E DG E M E NT S xv NAGUIB KANAWATI : A LIF E IN EGYPTOLOGY xvii ANN MCFARLANE NAGUIB KANAWATI : A BIBLIOGRAPHY xxvii SUSANNE BINDER , The Title 'Scribe of the Offering Table': Some Observations 1 GILLIAN BOWEN , The Spread of Christianity in Egypt: Archaeological Evidence 15 from Dakhleh and Kharga Oases EDWARD BROVARSKI , The Hare and Oryx Nomes in the First Intermediate 31 Period and Early Middle Kingdom VIVIENNE G.