The Writing of the Birds. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Before and After the Founding of Alexandria1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life in Egypt During the Coptic Period

Paper Abstracts of the First International Coptic Studies Conference Life in Egypt during the Coptic Period From Coptic to Arabic in the Christian Literature of Egypt Adel Y. Sidarus Evora, Portugal After having made the point on multilingualism in Egypt under Graeco- Roman domination (2008/2009), I intend to investigate the situation in the early centuries of Arab Islamic rule (7th–10th centuries). I will look for the shift from Coptic to Arabic in the Christian literature: the last period of literary expression in Coptic, with the decline of Sahidic and the rise of Bohairic, and the beginning of the new Arabic stage. I will try in particular to discover the reasons for the tardiness in the emergence of Copto-Arabic literature in comparison with Graeco-Arabic or Syro-Arabic, not without examining the literary output of the Melkite community of Egypt and of the other minority groups represented by the Jews, but also of Islamic literature in general. Was There a Coptic Community in Greece? Reading in the Text of Evliya Çelebi Ahmed M. M. Amin Fayoum University Evliya Çelebi (1611–1682) is a well-known Turkish traveler who was visiting Greece during 1667–71 and described the Greek cities in his interesting work "Seyahatname". Çelebi mentioned that there was an Egyptian community called "Pharaohs" in the city of Komotini; located in northern Greece, and they spoke their own language; the "Coptic dialect". Çelebi wrote around five pages about this subject and mentioned many incredible stories relating the Prophets Moses, Youssef and Mohamed with Egypt, and other stories about Coptic traditions, ethics and language as well. -

The Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Language Was Created by Sumerian Turks

Advances in Anthropology, 2017, 7, 197-250 http://www.scirp.org/journal/aa ISSN Online: 2163-9361 ISSN Print: 2163-9353 The Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Language Was Created by Sumerian Turks Metin Gündüz Retired Physician, Diplomate ABEM (American Board of Emergency Medicine), Izmir, Turkey How to cite this paper: Gündüz, M. (2017). Abstract The Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Lan- guage Was Created by Sumerian Turks. The “phonetic sound value of each and every hieroglyphic picture’s expressed Advances in Anthropology, 7, 197-250. and intended meaning as a verb or as a noun by the creators of the ancient https://doi.org/10.4236/aa.2017.74013 Egyptian hieroglyphic picture symbols, ‘exactly matches’, the same meaning” Received: August 2, 2017 as well as the “first letter of the corresponding meaning of the Turkish word’s Accepted: October 13, 2017 first syllable” with the currently spoken dialects of the Turkish language. The Published: October 16, 2017 exact intended sound value as well as the meaning of hieroglyphic pictures as Copyright © 2017 by author and nouns or verbs is individually and clearly expressed in the original hierog- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. lyphic pictures. This includes the 30 hieroglyphic pictures of well-known con- This work is licensed under the Creative sonants as well as some vowel sounds-of the language of the ancient Egyp- Commons Attribution International tians. There is no exception to this rule. Statistical and probabilistic certainty License (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ beyond any reasonable doubt proves the Turkish language connection. The Open Access hieroglyphic pictures match with 2 variables (the phonetic value and intended meaning). -

Egyptian Hieroglyphs CEEG 0909 a Workbook for an Introduction to Egyptian Hieroglyphs

An Introduction to Egyptian Hieroglyphs CEEG 0909 A Workbook for An Introduction to Egyptian Hieroglyphs C. Casey Wilbour Hall 301 christian [email protected] April 9, 2018 Contents Syllabus 2 Day 1 11 1-I-1 Rosetta Stone ................................................. 11 1-I-2 Calligraphy Practice 1 { Uniliterals ..................................... 13 1-I-4 Meet Your Classmates ............................................ 16 1-I-5 The Begatitudes ............................................... 17 1-I-6 Vocabulary { Uniliterals & Classifiers ................................... 19 Day 2 25 2-I-1 Timeline of Egyptian Languages ...................................... 25 2-I-2 Calligraphy Practice 2 { Biliterals ..................................... 27 2-I-3 Biliteral Chart ................................................ 32 2-I-4 Vocabulary { Biliterals & Classifiers .................................... 33 2-II-3 Vocabulary { Household Objects ...................................... 37 Day 3 39 3-I-1 Calligraphy Practice 3 { Multiliterals & Common Classifiers ....................... 39 3-I-2 Vocabulary { Multiliterals & Classifiers .................................. 43 3-I-3 Vocabulary { Suffix Pronouns, Parts of the Body ............................. 45 3-I-4 Parts of the Body .............................................. 47 3-II-3 Homework { Suffix Pronouns & Parts of the Body ............................ 48 Day 4 49 4-I-1 Vocabulary { Articles, Independent Pronouns, Family, Deities ...................... 49 4-I-4 Gods and Goddesses ............................................ -

Environmental and Social Impact Assessment

Submitted to : Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company EGAS ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL Prepared by: IMPACT ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORK Executive Summary EcoConServ Environmental Solutions 12 El-Saleh Ayoub St., Zamalek, Cairo, Egypt 11211 NATURAL GAS CONNECTION PROJECT Tel: + 20 2 27359078 – 2736 4818 IN 11 GOVERNORATES IN EGYPT Fax: + 20 2 2736 5397 E-mail: [email protected] (Final March 2014) Executive Summary ESIAF NG Connection 1.1M HHs- 11 governorates- March 2014 List of acronyms and abbreviations AFD Agence Française de Développement (French Agency for Development) AP Affected Persons ARP Abbreviated Resettlement Plan ALARP As Low As Reasonably Practical AST Above-ground Storage Tank BUTAGASCO The Egyptian Company for LPG distribution CAA Competent Administrative Authority CULTNAT Center for Documentation Of Cultural and Natural Heritage CAPMAS Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics CDA Community Development Association CRN Customer Reference Number EDHS Egyptian Demographic and Health Survey EHDR Egyptian Human Development Report 2010 EEAA Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency EGAS Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMU Environmental Management Unit ENIB Egyptian National Investment Bank ES Environmental and Social ESDV Emergency Shut Down Valve ESIAF Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Framework ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework ESMMF Environmental and Social Management and Monitoring Framework ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FGD Focus Group Discussion -

Raising of the Djed-Pillar

RAISING THE DJED PILLAR, THE RAMESSEUM DRAMATIC PAPYRUS Adapted by Stuart Tyson Smith from the translation & commentary of Kurt Sethe (1964, German translation by Jessika Akmenkalns), Henri Frankfort (1948), & Edward Wente (1980). Amenhotep III raises the Djed during his Heb-Sed in the tomb of Kheruef at Thebes. The annual ritual of “Raising the Djed” was the culmination of the larger “Mysteries of Osiris,” which commemorated the resurrection of Osiris after his murder by Seth and the restoration of the throne to Osiris’s son Horus. During the Coronation and Heb-Sed festival, Pharaoh took the place of Horus in the ritual, emphasizing the stability of his rule and his connection with the Osiris myth. Its phallic overtones alluded to the renewal of Pharaoh’s potency as ruler like Osiris in the myth. The Djed appears already in Predynastic art and was probably originally a fetish consisting of a pole with sheaves of grain attached. The Djed is described later on as the “Backbone of Osiris” in the Book of the Dead, but the original harvest and renewal symbolism was retained in the ritual. Although probably originally part of Ptah’s cult, the two gods were associated through a syncretism with Sokar, and the ceremony resonated with Osiris’s role as a god of the agricultural cycle. Cast: Lector Priest, Thoth, Geb, Horus/the King, Children of Horus, Osiris (as the Djed), Seth, Isis, Nephthys, Descendants of the King/Followers of Horus/Great Ones of Lower Egypt (royal princes and princesses), Musicians, Dancers and Singers, Followers of Seth/Great Ones of Upper Egypt, Spirit Seekers and the Keeper of the Two Feathers. -

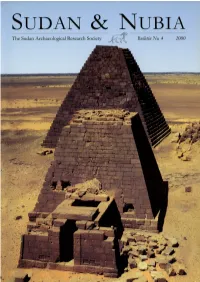

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Writing Systems Reading and Spelling

Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems LING 200: Introduction to the Study of Language Hadas Kotek February 2016 Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Outline 1 Writing systems 2 Reading and spelling Spelling How we read Slides credit: David Pesetsky, Richard Sproat, Janice Fon Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems What is writing? Writing is not language, but merely a way of recording language by visible marks. –Leonard Bloomfield, Language (1933) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and speech Until the 1800s, writing, not spoken language, was what linguists studied. Speech was often ignored. However, writing is secondary to spoken language in at least 3 ways: Children naturally acquire language without being taught, independently of intelligence or education levels. µ Many people struggle to learn to read. All human groups ever encountered possess spoken language. All are equal; no language is more “sophisticated” or “expressive” than others. µ Many languages have no written form. Humans have probably been speaking for as long as there have been anatomically modern Homo Sapiens in the world. µ Writing is a much younger phenomenon. Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems (Possibly) Independent Inventions of Writing Sumeria: ca. 3,200 BC Egypt: ca. 3,200 BC Indus Valley: ca. 2,500 BC China: ca. 1,500 BC Central America: ca. 250 BC (Olmecs, Mayans, Zapotecs) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and pictures Let’s define the distinction between pictures and true writing. -

Mints – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY

No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 USD1.00 = EGP5.96 USD1.00 = JPY77.91 (Exchange rate of January 2012) MiNTS: Misr National Transport Study Technical Report 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 THE MINTS FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................1-1 1.2.1 Study Scope and Objectives .........................................................................................................1-1 -

Relations in the Humanities Between Germany and Egypt

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg HANS ROBERT ROEMER Relations in the humanities between Germany and Egypt On the occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907 – 1982) Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Ägypten, Dauer und Wandel : Symposium anlässlich d. 75jährigen Bestehens d. Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Kairo. Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern, 1985, S.1 - 6 Relations in the Humanities between Germany and Egypt On the Occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907-1982) by HANS ROBERT ROEMER I The nucleus of the Institute whose jubilee we are celebrating today was established in Cairo in 1907 as »The Imperial German Institute for Egyptian Archaeology«. This was the result of a proposal presented by the Berlin Egyptologist Adolf Erman on behalf of the commission for the Egyptian Dictionary, formed by the German Academies of Sciences. This establishment had its antecedents in the 19th century, whose achievements were not only incomparable developments in the natural sciences, but also an unprecedented rise in the Humanities, a field in which German Egyptologists had contributed a substantial share. It is hence no exaggeration to consider the Institute the crowning and the climax of the excavation and research work accomplished earlier in this country. As a background, the German-Egyptian relations in the field of Humanities had already had a flourishing tradition. They had been inaugurated by Karl Richard Lepsius (1810-84) with a unique scientific work, completed in 1859, namely the publication of his huge twelve-volume book »Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Nubien« (»Monuments from Egypt and Nubia«), devoted to the results of a four-year expedition that he had undertaken. -

"Excavating the Old Kingdom. the Giza Necropolis and Other Mastaba

EGYPTIAN ART IN THE AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK This volume has been published in "lIljunction All ri~llIs r,'slTv"d, N"l'art 01 Ihis l'ul>li,';\II"n Tl'.ul,,,,,i,,,,, f... "u the I'r,'u,'h by .I;\nl<" 1'. AlIl'll with the exhibition «Egyptian Art in the Age of may be reproduced llI' ',",lIlsmilt"" by any '"l';\nS, of "'''Iys I>y Nadine (:I",rpion allll,kan-Philippe the Pyramids," organized by The Metropolitan electronic or mechanical, induding phorocopyin~, I,auer; by .Iohu Md )on;\ld of essays by Nicolas Museum of Art, New York; the Reunion des recording, or information retrieval system, with Grima I, Audran I."brousse, .lean I.eclam, and musees nationaux, Paris; and the Royal Ontario out permission from the publishers. Christiane Ziegler; hy .lane Marie Todd and Museum, Toronto, and held at the Gaieries Catharine H. Roehrig of entries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, from April 6 John P. O'Neill, Editor in Chief to July 12, 1999; The Metropolitan Museum of Carol Fuerstein, Editor, with the assistance of Maps adapted by Emsworth Design, Inc., from Art, New York, from September 16,1999, to Ellyn Childs Allison, Margaret Donovan, and Ziegler 1997a, pp. 18, 19 January 9, 2000; and the Royal Ontario Museum, Kathleen Howard Toronto, from February 13 to May 22, 2000. Patrick Seymour, Designer, after an original con Jacket/cover illustration: Detail, cat. no. 67, cept by Bruce Campbell King Menkaure and a Queen Gwen Roginsky and Hsiao-ning Tu, Production Frontispiece: Detail, cat. -

![The Rosetta Stone, British Museum, London Hieroglyphic, [From the Greek=Priestly Carving], Type of Writing Used in Ancient Egypt](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5650/the-rosetta-stone-british-museum-london-hieroglyphic-from-the-greek-priestly-carving-type-of-writing-used-in-ancient-egypt-755650.webp)

The Rosetta Stone, British Museum, London Hieroglyphic, [From the Greek=Priestly Carving], Type of Writing Used in Ancient Egypt

T h e R o s e t t a S t o n e Languages: Egyptian and Greek, Using three scripts -- Hieroglyphic, Demotic Egyptian, and Greek. Found 1799 by the French in Egypt Originally from 196 B.C. The Rosetta Stone, British Museum, London Hieroglyphic, [from the Greek=priestly carving], type of writing used in ancient Egypt. Similar pictographic styles of Crete, Asia Minor, and Central America and Mexico are also called hieroglyphics. Interpretation of Egyptian hieroglyphics, begun by Thomas Young and J. F. Champollion and others, is virtually complete. The meanings of hieroglyphics often seem arbitrary and are seldom obvious. Egyptian hieroglyphics were already perfected in the first dynasty (3110-2884 B.C.), but they began to go out of use in the Middle Kingdom and after 500 B.C. were virtually unused. There were basically 604 symbols that might be put to three types of uses (although few were used for all three purposes). 1) They could be used as ideograms, as when a sign resembling a snake meant "snake." [See chart above.] 2) They could be used as a phonogram (or a phonetic letter similar to our alphabet), as when the pictogram of an owl represented the sign or letter “m,” because the word for owl had “m” as its principal consonant sound. [It would be like us using a picture of a snake for the letter “s.”] 3) They could be used as a determinative, an unpronounced symbol placed after an ambiguous sign to indicate its classification (e.g., an eye to indicate that the preceding word has to do with looking or seeing). -

Proto-Elamite

L2/20192 20200921 Preliminary proposal to encode ProtoElamite in Unicode Anshuman Pandey [email protected] pandey.github.io/unicode September 21, 2020 Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Overview of the Sign Repertoire 3 2.1 Sign names . 4 2.2 Numeric signs . 4 2.3 Numeric signs with extended representations . 5 2.4 Complex capacity signs . 6 2.5 Complex graphemes . 7 2.6 Signs in compounds without independent attestation . 10 2.7 Alternate or variant forms . 11 2.8 Scribal designs . 11 3 Proposed Encoding Model 12 4 Proposed Characters 13 4.1 Numeric signs . 13 4.2 General ideographic signs . 17 5 Characters Not Suitable for Encoding 110 6 References 110 7 Acknowledgments 111 1 Preliminary proposal to encode ProtoElamite in Unicode Anshuman Pandey 1 Introduction The term ‘ProtoElamite’ refers to a writing system that was used at the beginning of the 3rd millenium BCE in the region to the east and southeast of Mesopotamia, known as Elam, which corresponds to the eastern portion of presentday Iran. The name was assigned by the French epigraphist JeanVincent Scheil in the early 20th century, who believed it to be the predecessor of a ‘proper’ Elamite script, which would have been used for recording the Elamite language, simply on account of the location of the tablets at Susa, which was the capital city of Elam. While no ‘proper’ descendent of the script has been identified, scholars continue to use the name ‘ProtoElamite’ as a matter of convention (Dahl 2012: 2). ProtoElamite is believed to have been developed from an accounting system used in Mesopotamia, in a manner similar to the development of ‘ProtoCuneiform’.