The Decipherment of Hieroglyphs and Richard Lepsius*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyberscribe 169-Sept 2009

Cyberscribe 169 1 CyberScribe 169 - September 2009 The CyberScribe did a little math this month and discovered that this issue marks the beginning of his fifteenth year as the writer of this column. He has no idea how many news items have been presented and discussed, but together we have covered a great deal of the Egyptology news during that time. Hopefully you have enjoyed the journey half as much as did the CyberScribe himself. And speaking of longevity, Zahi Hawass confirmed that he is about to retire from his position as head of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. Rumors have been rife for years as to how long he’d remain in this very important post. He has had a much longer tenure than most who held this important position, but at last his task seems to be ending. His times have been marked by controversy, confrontations, grandstanding and posturing…but at the same time he has made very substantial changes in Egyptology, in the monuments and museums of Egypt and in the preservation of Egypt’s heritage. Zahi Hawass has been the consummate showman, drawing immense good will and news attention to Egypt. Here is what he, himself, said about this retirement (read the entire article here, http://tiny.cc/4Q4wq), and understand that the quote below is just part of the interview: “Interviewer: Dr. Hawass, is it true that you plan to retire from the SCA next year? “Zahi Hawass: Yes, by law I have to retire. “Interviewer: What are your plans after leaving office? “Zahi Hawass: I will continue my excavations in the Valley of the Kings, writing books, give lectures everywhere.” This is surprising news, for the retirement of Hawass and the appointment of a successor has been a somewhat taboo subject among Egyptologists. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

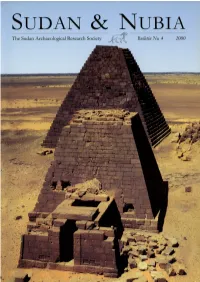

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

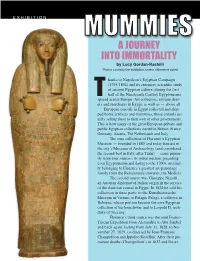

A Journey Into Immortality,” Which Opened on July 17 and Runs Until February 2, 2020

E X H I B I T I O N MUAM JOUMRNEY IES INTO IMMORTALITY by Lucy Gordan-Rastelli Photos courtesy the exhibition, unless ottherwise noted hanks to Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign (1798-1801) and its extensive scientific stud y of ancient Egyptian culture, during the first half of the Nineteenth Century Egyptomania spread across Europe. Art collectors, antique deal - Ters and merchants in Egypt, as well as — above all — European consuls in Egypt collected and ship- ped home artifacts and mummies, those consuls us- ually selling these to their own or other governments. This is how many of the great European private and public Egyptian collections started in Britain, France, Germany, Austria, The Netherlands and Italy . The core collection of Florence’s Egyptian Museum — founded in 1885 and today housed in the city’s Museum of Archaeology (and considered the second-best in Italy, after Turin) — came primar- ily from four sources, its initial nucleus preceding even Egyptomania and dating to the 1700s, original- ly be longing to Florence’s greatest art-patronage family from the Renaissance onwards, the Medicis. The second source was Giuseppe Nizzoli, an Austrian diplomat of Italian origin in the service of the Austrian consul in Egypt. In 1824 he sold his collection in three parts: to the Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna; to Pelagio Palagi, a collector in Bologna, whose portion became the core Egyptian collection of his hometown; and to Leopold II, arch- duke of Tuscany. Florence’s third source was the joint Franco- Tuscan Expedition from Alexandria to Abu Simbel and back again, lasting from July 31, 1828, to No - vember 27, 1829, co-directed by Jean-Fran çois Champollion and Ippolito Rosellini. -

Egyptian Religion a Handbook

A HANDBOOK OF EGYPTIAN RELIGION A HANDBOOK OF EGYPTIAN RELIGION BY ADOLF ERMAN WITH 130 ILLUSTRATIONS Published in tile original German edition as r handbook, by the Ge:r*rm/?'~?~~ltunf of the Berlin Imperial Morcums TRANSLATED BY A. S. GRIFFITH LONDON ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & CO. LTD. '907 Itic~mnoCLAY B 80~8,L~~II'ED BRIIO 6Tllll&I "ILL, E.C., AY" DUN,I*Y, RUFIOLP. ; ,, . ,ill . I., . 1 / / ., l I. - ' PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION THEvolume here translated appeared originally in 1904 as one of the excellent series of handbooks which, in addition to descriptive catalogues, are ~rovidedby the Berlin Museums for the guida,nce of visitors to their great collections. The haud- book of the Egyptian Religion seemed cspecially worthy of a wide circulation. It is a survey by the founder of the modern school of Egyptology in Germany, of perhaps tile most interest- ing of all the departments of this subject. The Egyptian religion appeals to some because of its endless variety of form, and the many phases of superstition and belief that it represents ; to others because of its early recognition of a high moral principle, its elaborate conceptions of a life aftcr death, and its connection with the development of Christianity; to others again no doubt because it explains pretty things dear to the collector of antiquities, and familiar objects in museums. Professor Erman is the first to present the Egyptian religion in historical perspective; and it is surely a merit in his worlc that out of his profound knowledge of the Egyptian texts, he permits them to tell their own tale almost in their own words, either by extracts or by summaries. -

Relations in the Humanities Between Germany and Egypt

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg HANS ROBERT ROEMER Relations in the humanities between Germany and Egypt On the occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907 – 1982) Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Ägypten, Dauer und Wandel : Symposium anlässlich d. 75jährigen Bestehens d. Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Kairo. Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern, 1985, S.1 - 6 Relations in the Humanities between Germany and Egypt On the Occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907-1982) by HANS ROBERT ROEMER I The nucleus of the Institute whose jubilee we are celebrating today was established in Cairo in 1907 as »The Imperial German Institute for Egyptian Archaeology«. This was the result of a proposal presented by the Berlin Egyptologist Adolf Erman on behalf of the commission for the Egyptian Dictionary, formed by the German Academies of Sciences. This establishment had its antecedents in the 19th century, whose achievements were not only incomparable developments in the natural sciences, but also an unprecedented rise in the Humanities, a field in which German Egyptologists had contributed a substantial share. It is hence no exaggeration to consider the Institute the crowning and the climax of the excavation and research work accomplished earlier in this country. As a background, the German-Egyptian relations in the field of Humanities had already had a flourishing tradition. They had been inaugurated by Karl Richard Lepsius (1810-84) with a unique scientific work, completed in 1859, namely the publication of his huge twelve-volume book »Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Nubien« (»Monuments from Egypt and Nubia«), devoted to the results of a four-year expedition that he had undertaken. -

The Writing of the Birds. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Before and After the Founding of Alexandria1

The Writing of the Birds. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Before and After the Founding of Alexandria1 Stephen Quirke, UCL Institute of Archaeology Abstract As Okasha El Daly has highlighted, qalam al-Tuyur “script of the birds” is one of the Arabic names used by the writers of the Ayyubid period and earlier to describe ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. The name may reflect the regular choice of Nile birds as signs for several consonants in the Ancient Egyptian language, such as the owl for “m”. However, the term also finds an ancestor in a rarer practice of hieroglyph users centuries earlier. From the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods and before, cursive manuscripts have preserved a list of sounds in the ancient Egyptian language, in the sequence used for the alphabet in South Arabian scripts known in Arabia before Arabic. The first “letter” in the hieroglyphic version is the ibis, the bird of Thoth, that is, of knowledge, wisdom and writing. In this paper I consider the research of recent decades into the Arabian connections to this “bird alphabet”. 1. Egyptological sources beyond traditional Egyptology Whether in our first year at school, or in our last year of university teaching, as life-long learners we engage with both empirical details, and frameworks of thought. In the history of ideas, we might borrow the names “philology” for the attentive study of the details, and “philosophy” for traditions of theoretical thinking.2As the classical Arabic tradition demonstrates in the wide scope of its enquiry and of its output, the quest for knowledge must combine both directions of research in order to move forward. -

"Excavating the Old Kingdom. the Giza Necropolis and Other Mastaba

EGYPTIAN ART IN THE AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK This volume has been published in "lIljunction All ri~llIs r,'slTv"d, N"l'art 01 Ihis l'ul>li,';\II"n Tl'.ul,,,,,i,,,,, f... "u the I'r,'u,'h by .I;\nl<" 1'. AlIl'll with the exhibition «Egyptian Art in the Age of may be reproduced llI' ',",lIlsmilt"" by any '"l';\nS, of "'''Iys I>y Nadine (:I",rpion allll,kan-Philippe the Pyramids," organized by The Metropolitan electronic or mechanical, induding phorocopyin~, I,auer; by .Iohu Md )on;\ld of essays by Nicolas Museum of Art, New York; the Reunion des recording, or information retrieval system, with Grima I, Audran I."brousse, .lean I.eclam, and musees nationaux, Paris; and the Royal Ontario out permission from the publishers. Christiane Ziegler; hy .lane Marie Todd and Museum, Toronto, and held at the Gaieries Catharine H. Roehrig of entries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, from April 6 John P. O'Neill, Editor in Chief to July 12, 1999; The Metropolitan Museum of Carol Fuerstein, Editor, with the assistance of Maps adapted by Emsworth Design, Inc., from Art, New York, from September 16,1999, to Ellyn Childs Allison, Margaret Donovan, and Ziegler 1997a, pp. 18, 19 January 9, 2000; and the Royal Ontario Museum, Kathleen Howard Toronto, from February 13 to May 22, 2000. Patrick Seymour, Designer, after an original con Jacket/cover illustration: Detail, cat. no. 67, cept by Bruce Campbell King Menkaure and a Queen Gwen Roginsky and Hsiao-ning Tu, Production Frontispiece: Detail, cat. -

The Origin of the Alphabet: an Examination of the Goldwasser Hypothesis

Colless, Brian E. The origin of the alphabet: an examination of the Goldwasser hypothesis Antiguo Oriente: Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Vol. 12, 2014 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la Institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Colless, Brian E. “The origin of the alphabet : an examination of the Goldwasser hypothesis” [en línea], Antiguo Oriente : Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente 12 (2014). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/origin-alphabet-goldwasser-hypothesis.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] . 03 Colless - Alphabet_Antiguo Oriente 09/06/2015 10:22 a.m. Página 71 THE ORIGIN OF THE ALPHABET: AN EXAMINATION OF THE GOLDWASSER HYPOTHESIS BRIAN E. COLLESS [email protected] Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand Summary: The Origin of the Alphabet Since 2006 the discussion of the origin of the Semitic alphabet has been given an impetus through a hypothesis propagated by Orly Goldwasser: the alphabet was allegedly invented in the 19th century BCE by illiterate Semitic workers in the Egyptian turquoise mines of Sinai; they saw the picturesque Egyptian inscriptions on the site and borrowed a number of the hieroglyphs to write their own language, using a supposedly new method which is now known by the technical term acrophony. The main weakness of the theory is that it ignores the West Semitic acrophonic syllabary, which already existed, and contained most of the letters of the alphabet. -

Jean Francois Champollion the Father of Egyptology by John Warren Anyone Who Has Studied Ancient Egypt Will Be Familiar with Jean Francois Champollion

Jean Francois Champollion The Father of Egyptology by John Warren Anyone who has studied ancient Egypt will be familiar with Jean Francois Champollion. He was, after all, credited with deciphering hieroglyphics from the Rosetta Stone and thus giving scholars the key to understanding hieroglyphics. For this effort along, he is frequently referred to as the Father of Egyptology, for he provided the foundation that scholars would need in order to truly understand the ancient Egyptians. Even though he suffered a stroke, dying at the age of forty-one, he himself added to our knowledge of this grand, ancient civilization by translating any number of Egyptian texts prior to his death. Champollion was born on December 23rd, 1790 in the town of Figeac, France to Jacques Champollion and Jeanne Francoise. He was their youngest son, and was educated originally by his elder brother, Jacques Joseph (1778-1867). While still at home, he attempted to teach himself a number of languages, including Hebrew, Arabic, Syriac, Chaldean and Chinese. In 1801, at the age of ten, he was sent off to study at the Lyceum in Grenoble. There, at the young age of sixteen, he red a paper before the Grenoble Academy proposing that the language of the Coptic Christians in contemporary Egypt was actually the same language spoken PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com language to be at least an evolutionary form of the language spoken in the pharaonic period, spiked with the tongues of its foreign invaders such as the Greeks. His studies continued at the College de France between 1807 and 1809, where he specialized in Oriental languages. -

Dipartimento Amministrativo Per Le Attivita' Istituzionali

Call for the selection of no. 1 temporary research associate position: The University of Pisa announces the public selection, assessed by qualifications and interview, for the assignment of n. 1 grant for research activities (hereinafter referred as “research grants”) as provided in the Annex A, with a specific tab for each project listing the reference structure, the research object, the scientific field, a summary of the background and skills of the fellow, information relating to the interview. Research grants will be funded on the POR FSE TOSCANA 2014-2020 resources in the frame of the Regione Toscana project Giovanisì (www.giovanisi.it ), aiming to enhance young people’s autonomy. Successful candidates will have to carry out their research activities mainly (at least 50% of the research activity period) with one of the operators of the regional cultural and creative network that collaborates on the project and is a mandatory component of the partnership. Contract duration: 24 months Gross annual salary: € 28.000,00 Admission requirements: - Hold a master degree at the time of application submission; - Be under the age of 36 by the application submission; Successful candidates currently holding other fellowships or research grants, are asked to renounce before the acceptance of the research grants referred in this notice, without prejudice to the provisions stated in the Law 30/12/2010 n. 240, art. 22, subparagraph III (exception laid down for the scholarships awarded by national or foreign institutions and aiming to complement the research activities with a stay abroad). The selection does not enable nationality limitations and follows the cross-cutting priorities of gender equality and equal opportunities. -

EGYPT in PISA by Lucy Gordan-Rastelli

EGYPT IN PISA by Lucy Gordan-Rastelli Torso segment of a y article “Mummies: A Journey Into Immortality” in the winter 2019-20 life-sized statue of Amenhotep III, found issue of the Journal (Vol. 30, No. 4,) concluded with: “The exhibition at Soleb in Nubia & ends with an excellent video of Guidotti [director of the Egyptian collec - today in the Egyptian collection of the Uni - tion in Florence] and the University of Pisa Egyptologist Dr. Flora Sil - versity of Pisa. vano discussing mummification techniques and how those evolved over M time.” My list of Italian museums with Egyptian collections does not in- 41 Kmt Left, Native of Pisa & father of Italian Egyptology Ippolito Rosellini (1800-1843) in a de - tail of a large painting by Guiseppe Angelelli depicting members of the Franco-Tuscan Ex - pedition to Egypt, 1828-1829. Above, Engraved frontispiece of Rosellini’s I Monumenti dell’Egitto e della Nubia , published in five volumes (1832-1844). clude Pisa, so I contacted Associate Prof. second-most important plaza, mag nificent an “adopted” one. Birga’s actual name Flora Silvano at Pisa’s University, to Piazza dei Cavalieri, or Knights’ Square. was Sofia Massimina Francesca Livia. find out more. A short walk away is Piazza dei Miraco- Her mother was Laura Rosellini, the From doing the research for my li, or Square of Miracles, where the city’s second to the last of Gaetano Rosellini’s article “Egypt on the Arno” (15:2, Sum - cathedral and baptistery and famous six children. Gaetano was the brother of mer 2004), and from Dennis Forbes’s Leaning Tower are located. -

The Cretan Script Family Includes the Carian Alphabet

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln CSE Journal Articles Computer Science and Engineering, Department of 2017 The rC etan Script Family Includes the Carian Alphabet Peter Z. Revesz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/csearticles Revesz, Peter Z., "The rC etan Script Family Includes the Carian Alphabet" (2017). CSE Journal Articles. 196. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/csearticles/196 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Computer Science and Engineering, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in CSE Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. MATEC Web of Conferences 125, 05019 (2017) DOI: 10.1051/ matecconf/201712505019 CSCC 2017 The Cretan Script Family Includes the Carian Alphabet Peter Z. Revesz1,a 1 Department of Computer Science, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, 68588, USA Abstract. The Cretan Script Family is a set of related writing systems that have a putative origin in Crete. Recently, Revesz [11] identified the Cretan Hieroglyphs, Linear A, Linear B, the Cypriot syllabary, and the Greek, Old Hungarian, Phoenician, South Arabic and Tifinagh alphabets as members of this script family and using bioinformatics algorithms gave a hypothetical evolutionary tree for their development and presented a map for their likely spread in the Mediterranean and Black Sea areas. The evolutionary tree and the map indicated some unknown writing system in western Anatolia to be the common origin of the Cypriot syllabary and the Old Hungarian alphabet.