The Cretan Script Family Includes the Carian Alphabet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anatolian Evidence Suggests That the Indo- European Laryngeals * H2 And

Indo-European Linguistics 6 (2018) 69–94 brill.com/ieul Anatolian evidence suggests that the Indo- European laryngeals *h2 and *h3 were uvular stops Alwin Kloekhorst Leiden University [email protected] Abstract In this article it will be argued that the Indo-European laryngeals *h2 and *h3, which recently have been identified as uvular fricatives, were in fact uvular stops in Proto- Indo-Anatolian. Also in the Proto-Anatolian and Proto-Luwic stages these sounds prob- ably were stops, not fricatives. Keywords Indo-European – laryngeals – phonological change – Indo-Anatolian 1 Background It is well-known that the Indo-European laryngeals *h2 and *h3 have in some environments survived in Hittite and Luwian as consonants that are spelled with the graphemes ḫ (in the cuneiform script) and h (in the hieroglyphic script).1 Although in handbooks it was usually stated that the exact phonetic interpretation of these graphemes is unclear,2 in recent years a consensus seems to have formed that they represent uvular fricatives (Kümmel 2007: 1 Although there is no full consensus on the question exactly in which environments *h2 and *h3 were retained as ḫ and h: especially the outcome of *h3 in Anatolian is debated (e.g. Kloekhorst 2006). Nevertheless, for the remainder of this article it is not crucial in which environments *h2 and *h3 yielded ḫ and h, only that they sometimes did. 2 E.g. Melchert 1994: 22; Hoffner & Melchert 2008: 38. © alwin kloekhorst, 2018 | doi:10.1163/22125892-00601003 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC license at the time of publication. -

Managing Order Relations in Mlbibtex∗

Managing order relations in MlBibTEX∗ Jean-Michel Hufflen LIFC (EA CNRS 4157) University of Franche-Comté 16, route de Gray 25030 BESANÇON CEDEX France hufflen (at) lifc dot univ-fcomte dot fr http://lifc.univ-fcomte.fr/~hufflen Abstract Lexicographical order relations used within dictionaries are language-dependent. First, we describe the problems inherent in automatic generation of multilin- gual bibliographies. Second, we explain how these problems are handled within MlBibTEX. To add or update an order relation for a particular natural language, we have to program in Scheme, but we show that MlBibTEX’s environment eases this task as far as possible. Keywords Lexicographical order relations, dictionaries, bibliographies, colla- tion algorithm, Unicode, MlBibTEX, Scheme. Streszczenie Porządek leksykograficzny w słownikach jest zależny od języka. Najpierw omó- wimy problemy powstające przy automatycznym generowaniu bibliografii wielo- języcznych. Następnie wyjaśnimy, jak są one traktowane w MlBibTEX-u. Do- danie lub zaktualizowanie zasad sortowania dla konkretnego języka naturalnego umożliwia program napisany w języku Scheme. Pokażemy, jak bardzo otoczenie MlBibTEX-owe ułatwia to zadanie. Słowa kluczowe Zasady sortowania leksykograficznego, słowniki, bibliografie, algorytmy sortowania leksykograficznego, Unikod, MlBibTEX, Scheme. 0 Introduction these items w.r.t. the alphabetical order of authors’ Looking for a word in a dictionary or for a name names. But the bst language of bibliography styles in a phone book is a common task. We get used [14] only provides a SORT function [13, Table 13.7] to the lexicographic order over a long time. More suitable for the English language, the commands for precisely, we get used to our own lexicographic or- accents and other diacritical signs being ignored by der, because it belongs to our cultural background. -

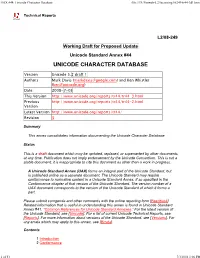

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database File:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-Tr44-3D1.Html

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database file:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-tr44-3d1.html Technical Reports L2/08-249 Working Draft for Proposed Update Unicode Standard Annex #44 UNICODE CHARACTER DATABASE Version Unicode 5.2 draft 1 Authors Mark Davis ([email protected]) and Ken Whistler ([email protected]) Date 2008-7-03 This Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-3.html Previous http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-2.html Version Latest Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/ Revision 3 Summary This annex consolidates information documenting the Unicode Character Database. Status This is a draft document which may be updated, replaced, or superseded by other documents at any time. Publication does not imply endorsement by the Unicode Consortium. This is not a stable document; it is inappropriate to cite this document as other than a work in progress. A Unicode Standard Annex (UAX) forms an integral part of the Unicode Standard, but is published online as a separate document. The Unicode Standard may require conformance to normative content in a Unicode Standard Annex, if so specified in the Conformance chapter of that version of the Unicode Standard. The version number of a UAX document corresponds to the version of the Unicode Standard of which it forms a part. Please submit corrigenda and other comments with the online reporting form [Feedback]. Related information that is useful in understanding this annex is found in Unicode Standard Annex #41, “Common References for Unicode Standard Annexes.” For the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see [Unicode]. For a list of current Unicode Technical Reports, see [Reports]. -

Tungumál, Letur Og Einkenni Hópa

Tungumál, letur og einkenni hópa Er letur ómissandi í baráttu hópa við ríkjandi öfl? Frá Tifinagh og rúnaristum til Pixação Þorleifur Kamban Þrastarson Lokaritgerð til BA-prófs Listaháskóli Íslands Hönnunar- og arkitektúrdeild Desember 2016 Í þessari ritgerð er reynt að rökstyðja þá fullyrðingu að letur sé mikilvægt og geti jafnvel undir vissum kringumstæðum verið eitt mikilvægasta vopnið í baráttu hópa fyrir tilveru sinni, sjálfsmynd og stað í samfélagi. Með því að líta á þrjú ólík dæmi, Tifinagh, rúnaletur og Pixação, hvert frá sínum stað, menningarheimi og tímabili er ætlunin að sýna hvernig saga leturs og týpógrafíu hefur samtvinnast og mótast af samfélagi manna og haldist í hendur við einkenni þjóða og hópa fólks sem samsama sig á einn eða annan hátt. Einkenni hópa myndast oft sem andsvar við ytri öflum sem ógna menningu, auði eða tilverurétti hópsins. Hópar nota mismunandi leturtýpur til þess að tjá sig, tengjast og miðla upplýsingum. Það skiptir ekki eingöngu máli hvað þú skrifar heldur hvernig, með hvaða aðferðum og á hvaða efni. Skilaboðin eru fólgin í letrinu sjálfu en ekki innihaldi letursins. Letur er útlit upplýsingakerfis okkar og hefur notkun ritmáls og leturs aldrei verið meiri í heiminum sem og læsi. Ritmál og letur eru algjörlega samofnir hlutir og ekki hægt að slíta annað frá öðru. Ekki er hægt að koma frá sér ritmáli nema í letri og þessi tvö hugtök flækjast því oft saman. Í ljósi athugana á þessum þremur dæmum í ritgerðinni dreg ég þá ályktun að letur spilar og hefur spilað mikilvægt hlutverk í einkennum þjóða og hópa. Letur getur, ásamt tungumálinu, stuðlað að því að viðhalda, skapa eða eyðileggja menningu og menningarlegar tenginga Tungumál, letur og einkenni hópa Er letur ómissandi í baráttu hópa við ríkjandi öfl? Frá Tifinagh og rúnaristum til Pixação Þorleifur Kamban Þrastarson Lokaritgerð til BA-prófs í Grafískri hönnun Leiðbeinandi: Óli Gneisti Sóleyjarson Grafísk hönnun Hönnunar- og arkitektúrdeild Desember 2016 Ritgerð þessi er 6 eininga lokaritgerð til BA-prófs í Grafískri hönnun. -

Herodotus' Conception of Foreign Languages

Histos () - HERODOTUS’ CONCEPTION OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES * Introduction In one of the most famous passages in his Histories , Herodotus has the Athe- nians give the reasons why they would never betray Greece (..): first and foremost, the images and temples of the gods, burnt and requiring vengeance, and then ‘the Greek thing’, being of the same blood and the same language, having common shrines and sacrifices and the same way of life. With race or blood, and with religious cult, language appears as one of the chief determinants of Greek identity. This impression is confirmed in Herodotus’ accounts of foreign peoples: language is—with religious customs, dress, hairstyles, sexual habits—one of the key items on Herodotus’ checklist of similarities and differences with foreign peoples. That language was an important element of what, to a Greek, it meant to be a Greek, should not perhaps be thought surprising. As is well known, the Greeks called non- Greeks βάρβαροι , a term usually taken to refer pejoratively to the babble of * This paper has been delivered in a number of different versions at St. Andrews, Newcastle, and at the Classical Association AGM. I should like to express my thanks to all those who took part in the subsequent discussions, and especially to Robert Fowler, Alan Griffiths, Robert Parker, Anna Morpurgo Davies and Stephanie West for their ex- tremely valuable comments on written drafts, to Hubert Petersmann for kindly sending me offprints of his publications, to Adrian Gratwick for his expert advice on a point of detail, and to David Colclough and Lucinda Platt for the repeated hospitality which al- lowed me to undertake the bulk of the research. -

ISO Basic Latin Alphabet

ISO basic Latin alphabet The ISO basic Latin alphabet is a Latin-script alphabet and consists of two sets of 26 letters, codified in[1] various national and international standards and used widely in international communication. The two sets contain the following 26 letters each:[1][2] ISO basic Latin alphabet Uppercase Latin A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z alphabet Lowercase Latin a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z alphabet Contents History Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters Names for the two subsets Names for the letters Timeline for encoding standards Timeline for widely used computer codes supporting the alphabet Representation Usage Alphabets containing the same set of letters Column numbering See also References History By the 1960s it became apparent to thecomputer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin script in their (ISO/IEC 646) 7-bit character-encoding standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. The standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 8859 (8-bit character encoding) and ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin script with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.[1] Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters The Unicode block that contains the alphabet is called "C0 Controls and Basic Latin". -

A Translation of the Malia Altar Stone

MATEC Web of Conferences 125, 05018 (2017) DOI: 10.1051/ matecconf/201712505018 CSCC 2017 A Translation of the Malia Altar Stone Peter Z. Revesz1,a 1 Department of Computer Science, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, 68588, USA Abstract. This paper presents a translation of the Malia Altar Stone inscription (CHIC 328), which is one of the longest known Cretan Hieroglyph inscriptions. The translation uses a synoptic transliteration to several scripts that are related to the Malia Altar Stone script. The synoptic transliteration strengthens the derived phonetic values and allows avoiding certain errors that would result from reliance on just a single transliteration. The synoptic transliteration is similar to a multiple alignment of related genomes in bioinformatics in order to derive the genetic sequence of a putative common ancestor of all the aligned genomes. 1 Introduction symbols. These attempts so far were not successful in deciphering the later two scripts. Cretan Hieroglyph is a writing system that existed in Using ideas and methods from bioinformatics, eastern Crete c. 2100 – 1700 BC [13, 14, 25]. The full Revesz [20] analyzed the evolutionary relationships decipherment of Cretan Hieroglyphs requires a consistent within the Cretan script family, which includes the translation of all known Cretan Hieroglyph texts not just following scripts: Cretan Hieroglyph, Linear A, Linear B the translation of some examples. In particular, many [6], Cypriot, Greek, Phoenician, South Arabic, Old authors have suggested translations for the Phaistos Disk, Hungarian [9, 10], which is also called rovásírás in the most famous and longest Cretan Hieroglyph Hungarian and also written sometimes as Rovas in inscription, but in general they were unable to show that English language publications, and Tifinagh. -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

Early-Alphabets-3.Pdf

Early Alphabets Alphabetic characteristics 1 Cretan Pictographs 11 Hieroglyphics 16 The Phoenician Alphabet 24 The Greek Alphabet 31 The Latin Alphabet 39 Summary 53 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS 1 / 53 Alphabetic characteristics 3,000 BCE Basic building blocks of written language GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 2 / 53 Early visual language systems were disparate and decentralized 3,000 BCE Protowriting, Cuneiform, Heiroglyphs and far Eastern writing all functioned differently Rebuses, ideographs, logograms, and syllabaries · GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 3 / 53 HIEROGLYPHICS REPRESENTING THE REBUS PRINCIPAL · BEE & LEAF · SEA & SUN · BELIEF AND SEASON GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 4 / 53 PETROGLYPHIC PICTOGRAMS AND IDEOGRAPHS · CIRCA 200 BCE · UTAH, UNITED STATES GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 5 / 53 LUWIAN LOGOGRAMS · CIRCA 1400 AND 1200 BCE · TURKEY GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 6 / 53 OLD PERSIAN SYLLABARY · 600 BCE GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 7 / 53 Alphabetic structure marked an enormous societal leap 3,000 BCE Power was reserved for those who could read and write · GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 8 / 53 What is an alphabet? Definition An alphabet is a set of visual symbols or characters used to represent the elementary sounds of a spoken language. –PM · GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 9 / 53 What is an alphabet? Definition They can be connected and combined to make visual configurations signifying sounds, syllables, and words uttered by the human mouth. -

The Carian Language HANDBOOK of ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE the NEAR and MIDDLE EAST

The Carian Language HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-SIX The Carian Language by Ignacio J. Adiego with an appendix by Koray Konuk BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Adiego Lajara, Ignacio-Javier. The Carian language / by Ignacio J. Adiego ; with an appendix by Koray Konuk. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 86). Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13 : 978-90-04-15281-6 (hardback) ISBN-10 : 90-04-15281-4 (hardback) 1. Carian language. 2. Carian language—Writing. 3. Inscriptions, Carian—Egypt. 4. Inscriptions, Carian—Turkey—Caria. I. Title. II. P946.A35 2006 491’.998—dc22 2006051655 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 15281 4 ISBN-13 978 90 04 15281 6 © Copyright 2007 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Hotei Publishers, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

The Origins of the Alphabet but Their Numbers Tally Into of Greeks and Later Through Their Manuscripts

1 ORIGINS OF THE ALPHABET gchgchgchgchgchgchgchgcggchgchgchgchgchgchggchch disadvantages to this system: not the development of the alphabet, letters developed as a natural result of only were the symbols complex, for it was through the auspices the use of the fl exible reed pen for writing The origins of the alphabet but their numbers tally into of Greeks and later through their manuscripts. Lowercase letters for the begin within the shadowy realms of the tens of thousands, making cultural admirers, the Romans, most part require fewer strokes for their prehistory. At some time within that learning diffi cult and writing slow. that the alphabet was to fi nally formation, allowing the scribes to fi t more shadowed prehistory, humankind An early culture that take on a distinct resemblance letters in a line of type. The combination began to communicate visually. inspired to innovate a simpler, to the modern Western alphabet. of speed and space conservation was Motivated by the need to communicate more effi cient writing system was important to monks writing lengthy facts about the environment around the Phoenicians. The Phoenicians manuscripts on expensive parchment, them, humans made simple drawings v were a wide-fl ung trading people When the Romans adopted and the use of lowercase letters was widely of everyday objects such as people, of great vitality, with complex the Greek alphabet, along with adopted in animals, weapons and so forth. These business transactions that other aspects of Greek culture, a relatively object drawings are called pictographs. required accurate record keeping. they continued the development short time It was through their need for and usage of the alphabet. -

Old Cyrillic in Unicode*

Old Cyrillic in Unicode* Ivan A Derzhanski Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences [email protected] The current version of the Unicode Standard acknowledges the existence of a pre- modern version of the Cyrillic script, but its support thereof is limited to assigning code points to several obsolete letters. Meanwhile mediæval Cyrillic manuscripts and some early printed books feature a plethora of letter shapes, ligatures, diacritic and punctuation marks that want proper representation. (In addition, contemporary editions of mediæval texts employ a variety of annotation signs.) As generally with scripts that predate printing, an obvious problem is the abundance of functional, chronological, regional and decorative variant shapes, the precise details of whose distribution are often unknown. The present contents of the block will need to be interpreted with Old Cyrillic in mind, and decisions to be made as to which remaining characters should be implemented via Unicode’s mechanism of variation selection, as ligatures in the typeface, or as code points in the Private space or the standard Cyrillic block. I discuss the initial stage of this work. The Unicode Standard (Unicode 4.0.1) makes a controversial statement: The historical form of the Cyrillic alphabet is treated as a font style variation of modern Cyrillic because the historical forms are relatively close to the modern appearance, and because some of them are still in modern use in languages other than Russian (for example, U+0406 “I” CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER I is used in modern Ukrainian and Byelorussian). Some of the letters in this range were used in modern typefaces in Russian and Bulgarian.