A Translation of the Malia Altar Stone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database File:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-Tr44-3D1.Html

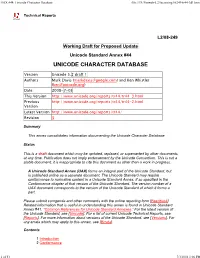

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database file:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-tr44-3d1.html Technical Reports L2/08-249 Working Draft for Proposed Update Unicode Standard Annex #44 UNICODE CHARACTER DATABASE Version Unicode 5.2 draft 1 Authors Mark Davis ([email protected]) and Ken Whistler ([email protected]) Date 2008-7-03 This Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-3.html Previous http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-2.html Version Latest Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/ Revision 3 Summary This annex consolidates information documenting the Unicode Character Database. Status This is a draft document which may be updated, replaced, or superseded by other documents at any time. Publication does not imply endorsement by the Unicode Consortium. This is not a stable document; it is inappropriate to cite this document as other than a work in progress. A Unicode Standard Annex (UAX) forms an integral part of the Unicode Standard, but is published online as a separate document. The Unicode Standard may require conformance to normative content in a Unicode Standard Annex, if so specified in the Conformance chapter of that version of the Unicode Standard. The version number of a UAX document corresponds to the version of the Unicode Standard of which it forms a part. Please submit corrigenda and other comments with the online reporting form [Feedback]. Related information that is useful in understanding this annex is found in Unicode Standard Annex #41, “Common References for Unicode Standard Annexes.” For the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see [Unicode]. For a list of current Unicode Technical Reports, see [Reports]. -

Tungumál, Letur Og Einkenni Hópa

Tungumál, letur og einkenni hópa Er letur ómissandi í baráttu hópa við ríkjandi öfl? Frá Tifinagh og rúnaristum til Pixação Þorleifur Kamban Þrastarson Lokaritgerð til BA-prófs Listaháskóli Íslands Hönnunar- og arkitektúrdeild Desember 2016 Í þessari ritgerð er reynt að rökstyðja þá fullyrðingu að letur sé mikilvægt og geti jafnvel undir vissum kringumstæðum verið eitt mikilvægasta vopnið í baráttu hópa fyrir tilveru sinni, sjálfsmynd og stað í samfélagi. Með því að líta á þrjú ólík dæmi, Tifinagh, rúnaletur og Pixação, hvert frá sínum stað, menningarheimi og tímabili er ætlunin að sýna hvernig saga leturs og týpógrafíu hefur samtvinnast og mótast af samfélagi manna og haldist í hendur við einkenni þjóða og hópa fólks sem samsama sig á einn eða annan hátt. Einkenni hópa myndast oft sem andsvar við ytri öflum sem ógna menningu, auði eða tilverurétti hópsins. Hópar nota mismunandi leturtýpur til þess að tjá sig, tengjast og miðla upplýsingum. Það skiptir ekki eingöngu máli hvað þú skrifar heldur hvernig, með hvaða aðferðum og á hvaða efni. Skilaboðin eru fólgin í letrinu sjálfu en ekki innihaldi letursins. Letur er útlit upplýsingakerfis okkar og hefur notkun ritmáls og leturs aldrei verið meiri í heiminum sem og læsi. Ritmál og letur eru algjörlega samofnir hlutir og ekki hægt að slíta annað frá öðru. Ekki er hægt að koma frá sér ritmáli nema í letri og þessi tvö hugtök flækjast því oft saman. Í ljósi athugana á þessum þremur dæmum í ritgerðinni dreg ég þá ályktun að letur spilar og hefur spilað mikilvægt hlutverk í einkennum þjóða og hópa. Letur getur, ásamt tungumálinu, stuðlað að því að viðhalda, skapa eða eyðileggja menningu og menningarlegar tenginga Tungumál, letur og einkenni hópa Er letur ómissandi í baráttu hópa við ríkjandi öfl? Frá Tifinagh og rúnaristum til Pixação Þorleifur Kamban Þrastarson Lokaritgerð til BA-prófs í Grafískri hönnun Leiðbeinandi: Óli Gneisti Sóleyjarson Grafísk hönnun Hönnunar- og arkitektúrdeild Desember 2016 Ritgerð þessi er 6 eininga lokaritgerð til BA-prófs í Grafískri hönnun. -

Cuneiform and Hieroglyphs 11

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

The Carian Language HANDBOOK of ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE the NEAR and MIDDLE EAST

The Carian Language HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-SIX The Carian Language by Ignacio J. Adiego with an appendix by Koray Konuk BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Adiego Lajara, Ignacio-Javier. The Carian language / by Ignacio J. Adiego ; with an appendix by Koray Konuk. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 86). Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13 : 978-90-04-15281-6 (hardback) ISBN-10 : 90-04-15281-4 (hardback) 1. Carian language. 2. Carian language—Writing. 3. Inscriptions, Carian—Egypt. 4. Inscriptions, Carian—Turkey—Caria. I. Title. II. P946.A35 2006 491’.998—dc22 2006051655 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 15281 4 ISBN-13 978 90 04 15281 6 © Copyright 2007 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Hotei Publishers, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Writing Systems Reading and Spelling

Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems LING 200: Introduction to the Study of Language Hadas Kotek February 2016 Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Outline 1 Writing systems 2 Reading and spelling Spelling How we read Slides credit: David Pesetsky, Richard Sproat, Janice Fon Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems What is writing? Writing is not language, but merely a way of recording language by visible marks. –Leonard Bloomfield, Language (1933) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and speech Until the 1800s, writing, not spoken language, was what linguists studied. Speech was often ignored. However, writing is secondary to spoken language in at least 3 ways: Children naturally acquire language without being taught, independently of intelligence or education levels. µ Many people struggle to learn to read. All human groups ever encountered possess spoken language. All are equal; no language is more “sophisticated” or “expressive” than others. µ Many languages have no written form. Humans have probably been speaking for as long as there have been anatomically modern Homo Sapiens in the world. µ Writing is a much younger phenomenon. Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems (Possibly) Independent Inventions of Writing Sumeria: ca. 3,200 BC Egypt: ca. 3,200 BC Indus Valley: ca. 2,500 BC China: ca. 1,500 BC Central America: ca. 250 BC (Olmecs, Mayans, Zapotecs) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and pictures Let’s define the distinction between pictures and true writing. -

This Document Serves As a Summary of the UC Berkeley Script Encoding Initiative's Recent Activities. Proposals Recently Submit

L2/11‐049 TO: Unicode Technical Committee FROM: Deborah Anderson, Project Leader, Script Encoding Initiative, UC Berkeley DATE: 3 February 2011 RE: Liaison Report from UC Berkeley (Script Encoding Initiative) This document serves as a summary of the UC Berkeley Script Encoding Initiative’s recent activities. Proposals recently submitted to the UTC that have involved SEI assistance include: Afaka (Everson) [preliminary] Elbasan (Everson and Elsie) Khojki (Pandey) Khudawadi (Pandey) Linear A (Everson and Younger) [revised] Nabataean (Everson) Woleai (Everson) [preliminary] Webdings/Wingdings Ongoing work continues on the following: Anatolian Hieroglyphs (Everson) Balti (Pandey) Dhives Akuru (Pandey) Gangga Malayu (Pandey) Gondi (Pandey) Hungarian Kpelle (Everson and Riley) Landa (Pandey) Loma (Everson) Mahajani (Pandey) Maithili (Pandey) Manichaean (Everson and Durkin‐Meisterernst) Mende (Everson) Modi (Pandey) Nepali script (Pandey) Old Albanian alphabets Pahawh Hmong (Everson) Pau Cin Hau Alphabet and Pau Cin Hau Logographs (Pandey) Rañjana (Everson) Siyaq (and related symbols) (Pandey) Soyombo (Pandey) Tani Lipi (Pandey) Tolong Siki (Pandey) Warang Citi (Everson) Xawtaa Dorboljin (Mongolian Horizontal Square script) (Pandey) Zou (Pandey) Proposals for unencoded Greek papyrological signs, as well as for various Byzantine Greek and Sumero‐Akkadian characters are being discussed. A proposal for the Palaeohispanic script is also underway. Deborah Anderson is encouraging additional participation from Egyptologists for future work on Ptolemaic signs. She has received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and support from Google to cover work through 2011. . -

Documenting Endangered Alphabets

Documenting endangered alphabets Industry Focus Tim Brookes Three years ago, acting on a notion so whimsi- cal I assumed it was a kind of presenile monoma- nia, I began carving endangered alphabets. The Tdisclaimers start right away. I’m not a linguist, an anthropologist, a cultural historian or even a woodworker. I’m a writer — but I had recently started carving signs for friends and family, and I stumbled on Omniglot.com, an online encyclo- pedia of the world’s writing systems, and several things had struck me forcibly. For a start, even though the world has more than 6,000 Figure 1: Tifinagh. languages (some of which will be extinct even by the time this article goes to press), it has fewer than 100 scripts, and perhaps a passing them on as a series of items for consideration and dis- third of those are endangered. cussion. For example, what does a written language — any writ- Working with a set of gouges and a paintbrush, I started to ten language — look like? The Endangered Alphabets highlight document as many of these scripts as I could find, creating three this question in a number of interesting ways. As the forces of exhibitions and several dozen individual pieces that depicted globalism erode scripts such as these, the number of people who words, phrases, sentences or poems in Syriac, Bugis, Baybayin, can write them dwindles, and the range of examples of each Samaritan, Makassarese, Balinese, Javanese, Batak, Sui, Nom, script is reduced. My carvings may well be the only examples Cherokee, Inuktitut, Glagolitic, Vai, Bassa Vah, Tai Dam, Pahauh of, say, Samaritan script or Tifinagh that my visitors ever see. -

Linguistic Study About the Origins of the Aegean Scripts

Anistoriton Journal, vol. 15 (2016-2017) Essays 1 Cretan Hieroglyphics The Ornamental and Ritual Version of the Cretan Protolinear Script The Cretan Hieroglyphic script is conventionally classified as one of the five Aegean scripts, along with Linear-A, Linear-B and the two Cypriot Syllabaries, namely the Cypro-Minoan and the Cypriot Greek Syllabary, the latter ones being regarded as such because of their pictographic and phonetic similarities to the former ones. Cretan Hieroglyphics are encountered in the Aegean Sea area during the 2nd millennium BC. Their relationship to Linear-A is still in dispute, while the conveyed language (or languages) is still considered unknown. The authors argue herein that the Cretan Hieroglyphic script is simply a decorative version of Linear-A (or, more precisely, of the lost Cretan Protolinear script that is the ancestor of all the Aegean scripts) which was used mainly by the seal-makers or for ritual usage. The conveyed language must be a conservative form of Sumerian, as Cretan Hieroglyphic is strictly associated with the original and mainstream Minoan culture and religion – in contrast to Linear-A which was used for several other languages – while the phonetic values of signs have the same Sumerian origin as in Cretan Protolinear. Introduction The three syllabaries that were used in the Aegean area during the 2nd millennium BC were the Cretan Hieroglyphics, Linear-A and Linear-B. The latter conveys Mycenaean Greek, which is the oldest known written form of Greek, encountered after the 15th century BC. Linear-A is still regarded as a direct descendant of the Cretan Hieroglyphics, conveying the unknown language or languages of the Minoans (Davis 2010). -

Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2017.08.38

Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2017.08.38 http://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2017/2017-08-38 BMCR 2017.08.38 on the BMCR blog Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2017.08.38 Paola Cotticelli-Kurras, Alfredo Rizza (ed.), Variation within and among Writing Systems: Concepts and Methods in the Analysis of Ancient Written Documents. LautSchriftSprache / ScriptandSound. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 2017. Pp. 384. ISBN 9783954901456. €98.00. Reviewed by Anna P. Judson, Gonville & Caius College, University of Cambridge ([email protected]) Table of Contents [Authors and titles are listed at the end of the review.] This book is the first of a new series, ‘LautSchriftSprache / ScriptandSound’, focusing on the field of graphemics (the study of writing systems), in particular historical graphemics. As the traditional view of writing as (merely) a way of representing speech has given way to a more nuanced understanding of writing as a different, rather than secondary, means of communication,1 graphemics has become an increasingly popular field; it is also necessarily an interdisciplinary field, since it incorporates the study not only of written texts’ linguistic features, but also broader aspects such as their visual features, material supports, and contexts of production and reading. A series dedicated to the study of graphemics across multiple academic disciplines is therefore a very welcome development. This first volume presents twenty-one papers from the third ‘LautSchriftSprache’ conference, held in Verona in 2013. In their introduction, the editors stress that the aim is to present studies of writing systems with as wide a scope as possible in terms of location, chronology, writing support, cultural context, and function. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

Universal Iconography in Writing Systems Evidence and Explanation in the Easter Island

Universal Iconography in Writing Systems Evidence and Explanation in the Easter Island and Indus Valley Scripts Richard E. McDorman © 2009 Summary Iconography has played a central role in the development of writing systems. That all independently derived ancient scripts began as arrangements of pictograms before evolving into their elaborated forms evinces the fundamental importance of iconography in the evolution of writing. Symbols of the earliest logographic writing systems are characterized by a number of iconographic principles. Elucidation of these iconographic principles provides a theoretical framework for the analysis of structural similarities in unrelated, independently evolved writing systems. Two such writing systems are the ancient Indus Valley and Easter Island scripts. Although separated by vast tracts of time and space, the two writing systems share between forty and fifty complex characters, a problem first identified by Hevesy in 1932. Previous attempts to explain the similarities between the Indus Valley script and the rongorongo of Easter Island, which have relied on notions of cultural contact or historical derivation, have proved unfruitful. In reconsidering the problem, a novel approach based on comparative iconographic principles can explain the resemblances between the two scripts as the product of the universal iconography displayed by all writing systems in their pictographic and logographic stages of development. The principle of iconography in writing systems It has been noted that graphically similar symbols have been employed to represent semantically cognate ideas in a number of early, unrelated writing systems. 1 One explanation for this phenomenon is that there exist universal iconographic principles that bear upon the minds of those creating these scripts, thereby influencing the graphical form of the glyphs 2 that comprise the newly created writing systems.