Language Ideologies in Morocco Sybil Bullock Connecticut College, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arabization and Linguistic Domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa Mohand Tilmatine

Arabization and linguistic domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa Mohand Tilmatine To cite this version: Mohand Tilmatine. Arabization and linguistic domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa. Language Empires in Comparative Perspective, DE GRUYTER, pp.1-16, 2015, Koloniale und Postkoloniale Linguistik / Colonial and Postcolonial Linguistics, 978-3-11-040836-2. hal-02182976 HAL Id: hal-02182976 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02182976 Submitted on 14 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arabization and linguistic domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa Mohand Tilmatine To cite this version: Mohand Tilmatine. Arabization and linguistic domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa. Language Empires in Comparative Perspective, DE GRUYTER, pp.1-16, 2015, Koloniale und Postkoloniale Linguistik / Colonial and Postcolonial Linguistics 978-3-11-040836-2. hal-02182976 HAL Id: hal-02182976 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02182976 Submitted on 14 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. -

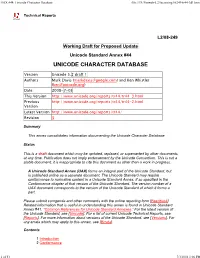

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database File:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-Tr44-3D1.Html

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database file:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-tr44-3d1.html Technical Reports L2/08-249 Working Draft for Proposed Update Unicode Standard Annex #44 UNICODE CHARACTER DATABASE Version Unicode 5.2 draft 1 Authors Mark Davis ([email protected]) and Ken Whistler ([email protected]) Date 2008-7-03 This Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-3.html Previous http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-2.html Version Latest Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/ Revision 3 Summary This annex consolidates information documenting the Unicode Character Database. Status This is a draft document which may be updated, replaced, or superseded by other documents at any time. Publication does not imply endorsement by the Unicode Consortium. This is not a stable document; it is inappropriate to cite this document as other than a work in progress. A Unicode Standard Annex (UAX) forms an integral part of the Unicode Standard, but is published online as a separate document. The Unicode Standard may require conformance to normative content in a Unicode Standard Annex, if so specified in the Conformance chapter of that version of the Unicode Standard. The version number of a UAX document corresponds to the version of the Unicode Standard of which it forms a part. Please submit corrigenda and other comments with the online reporting form [Feedback]. Related information that is useful in understanding this annex is found in Unicode Standard Annex #41, “Common References for Unicode Standard Annexes.” For the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see [Unicode]. For a list of current Unicode Technical Reports, see [Reports]. -

Tungumál, Letur Og Einkenni Hópa

Tungumál, letur og einkenni hópa Er letur ómissandi í baráttu hópa við ríkjandi öfl? Frá Tifinagh og rúnaristum til Pixação Þorleifur Kamban Þrastarson Lokaritgerð til BA-prófs Listaháskóli Íslands Hönnunar- og arkitektúrdeild Desember 2016 Í þessari ritgerð er reynt að rökstyðja þá fullyrðingu að letur sé mikilvægt og geti jafnvel undir vissum kringumstæðum verið eitt mikilvægasta vopnið í baráttu hópa fyrir tilveru sinni, sjálfsmynd og stað í samfélagi. Með því að líta á þrjú ólík dæmi, Tifinagh, rúnaletur og Pixação, hvert frá sínum stað, menningarheimi og tímabili er ætlunin að sýna hvernig saga leturs og týpógrafíu hefur samtvinnast og mótast af samfélagi manna og haldist í hendur við einkenni þjóða og hópa fólks sem samsama sig á einn eða annan hátt. Einkenni hópa myndast oft sem andsvar við ytri öflum sem ógna menningu, auði eða tilverurétti hópsins. Hópar nota mismunandi leturtýpur til þess að tjá sig, tengjast og miðla upplýsingum. Það skiptir ekki eingöngu máli hvað þú skrifar heldur hvernig, með hvaða aðferðum og á hvaða efni. Skilaboðin eru fólgin í letrinu sjálfu en ekki innihaldi letursins. Letur er útlit upplýsingakerfis okkar og hefur notkun ritmáls og leturs aldrei verið meiri í heiminum sem og læsi. Ritmál og letur eru algjörlega samofnir hlutir og ekki hægt að slíta annað frá öðru. Ekki er hægt að koma frá sér ritmáli nema í letri og þessi tvö hugtök flækjast því oft saman. Í ljósi athugana á þessum þremur dæmum í ritgerðinni dreg ég þá ályktun að letur spilar og hefur spilað mikilvægt hlutverk í einkennum þjóða og hópa. Letur getur, ásamt tungumálinu, stuðlað að því að viðhalda, skapa eða eyðileggja menningu og menningarlegar tenginga Tungumál, letur og einkenni hópa Er letur ómissandi í baráttu hópa við ríkjandi öfl? Frá Tifinagh og rúnaristum til Pixação Þorleifur Kamban Þrastarson Lokaritgerð til BA-prófs í Grafískri hönnun Leiðbeinandi: Óli Gneisti Sóleyjarson Grafísk hönnun Hönnunar- og arkitektúrdeild Desember 2016 Ritgerð þessi er 6 eininga lokaritgerð til BA-prófs í Grafískri hönnun. -

A Translation of the Malia Altar Stone

MATEC Web of Conferences 125, 05018 (2017) DOI: 10.1051/ matecconf/201712505018 CSCC 2017 A Translation of the Malia Altar Stone Peter Z. Revesz1,a 1 Department of Computer Science, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, 68588, USA Abstract. This paper presents a translation of the Malia Altar Stone inscription (CHIC 328), which is one of the longest known Cretan Hieroglyph inscriptions. The translation uses a synoptic transliteration to several scripts that are related to the Malia Altar Stone script. The synoptic transliteration strengthens the derived phonetic values and allows avoiding certain errors that would result from reliance on just a single transliteration. The synoptic transliteration is similar to a multiple alignment of related genomes in bioinformatics in order to derive the genetic sequence of a putative common ancestor of all the aligned genomes. 1 Introduction symbols. These attempts so far were not successful in deciphering the later two scripts. Cretan Hieroglyph is a writing system that existed in Using ideas and methods from bioinformatics, eastern Crete c. 2100 – 1700 BC [13, 14, 25]. The full Revesz [20] analyzed the evolutionary relationships decipherment of Cretan Hieroglyphs requires a consistent within the Cretan script family, which includes the translation of all known Cretan Hieroglyph texts not just following scripts: Cretan Hieroglyph, Linear A, Linear B the translation of some examples. In particular, many [6], Cypriot, Greek, Phoenician, South Arabic, Old authors have suggested translations for the Phaistos Disk, Hungarian [9, 10], which is also called rovásírás in the most famous and longest Cretan Hieroglyph Hungarian and also written sometimes as Rovas in inscription, but in general they were unable to show that English language publications, and Tifinagh. -

On the Case System of Kabyle*

On the Case System of Kabyle* Lydia Felice Georgetown University SUMMARY This paper examines the state alternation in Kabyle, arguing that state is the morphological realization of Case. The free state is accusative case, and the construct state is nominative case. Taking morphological patterns and syntactic distribution into account, Kabyle is found to be a Type 2 marked nominative language. Both states, or cases, are morphologically marked. The free state is the default case. This analysis accounts for the bulk of the distribution of free state and construct state nouns, and situates Kabyle as belonging to a typologically rare alignment system that is concentrated in Afroasiatic and African languages. RÉSUMÉ Cet article examine l’alternance d’état en kabyle, en faisant valoir que l’état est la réalisation morphologique de cas. L’état libre est un cas accusatif, et l’état d’annexion est un cas nominatif. Compte tenu des patrons morphologiques et de la distribution syntaxique, le kabyle s’avère être une langue à nominatif marqué de Type 2 où les deux états, ou bien les cas, sont marqués morphologiquement et que l’état libre est le cas par défaut. Cette analyse représente la majeure partie de la distribution des noms d’état libre et d’état d’annexion et situe le kabyle comme appartenant à un système d’alignement typologiquement rare et concentré dans les langues afro-asiatiques et africaines. * Thank you to Karima Ouazar for her patience and generosity in teaching me about her language. Thank you to Jessica Coon and Ruth Kramer for guidance throughout this project, as well as Lisa Travis, Hector Campos, and audiences at NACAL 46 and WOCAL 9 for valuable feedback. -

Documenting Endangered Alphabets

Documenting endangered alphabets Industry Focus Tim Brookes Three years ago, acting on a notion so whimsi- cal I assumed it was a kind of presenile monoma- nia, I began carving endangered alphabets. The Tdisclaimers start right away. I’m not a linguist, an anthropologist, a cultural historian or even a woodworker. I’m a writer — but I had recently started carving signs for friends and family, and I stumbled on Omniglot.com, an online encyclo- pedia of the world’s writing systems, and several things had struck me forcibly. For a start, even though the world has more than 6,000 Figure 1: Tifinagh. languages (some of which will be extinct even by the time this article goes to press), it has fewer than 100 scripts, and perhaps a passing them on as a series of items for consideration and dis- third of those are endangered. cussion. For example, what does a written language — any writ- Working with a set of gouges and a paintbrush, I started to ten language — look like? The Endangered Alphabets highlight document as many of these scripts as I could find, creating three this question in a number of interesting ways. As the forces of exhibitions and several dozen individual pieces that depicted globalism erode scripts such as these, the number of people who words, phrases, sentences or poems in Syriac, Bugis, Baybayin, can write them dwindles, and the range of examples of each Samaritan, Makassarese, Balinese, Javanese, Batak, Sui, Nom, script is reduced. My carvings may well be the only examples Cherokee, Inuktitut, Glagolitic, Vai, Bassa Vah, Tai Dam, Pahauh of, say, Samaritan script or Tifinagh that my visitors ever see. -

Léxico Español Actual Vi

DIPARTIMENTO DI STUDI LINGUISTICI E CULTURALI COMPARATI LÉXICO ESPAÑOL ACTUAL VI edición de Luis Luque Toro Rocío Luque Léxico Español Actual VI Edición de Luis Luque Toro y Rocío Luque © 2019 Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia ISBN 978-99-7543-477-9 Con la contribución de: Libreria Editrice Cafoscarina Dorsoduro 3259, 30123 Venezia www.cafoscarina.it Prima edizione dicembre 2019 Índice Introducción 7 EDUARDO DE AGREDA COSO Estudio aspectual y léxico de las formas verbales pretéritas en la obra Hay que deshacer la casa de Sebastián Junyent para el estudiante de ELE 9 MANUEL ALVAR EZQUERRA La Biblioteca Virtual de la Filología Española (BVFE): de su nacimiento a su consolidación. Situación en octubre de 2015 33 M.ª AUXILIADORA CASTILLO CARBALLO La nominalidad fraseológica y su proyección lexicográfica 63 CARMEN CAZORLA VIVAS Marcación dialectal en la lexicografía del español de la primera mitad del siglo XIX: lexicografía monolingüe frente a lexicografía bilingüe español-francés 85 JUAN MANUEL GARCÍA PLATERO Palabras nuevas y sanción lexicográfica 115 LUIS LUQUE TORO Las locuciones adverbiales introducidas por la terna preposicional a, de, en 133 FRANCISCO A. MARCOS MARÍN El léxico latino en bereber en el marco del estudio de los romances africanos y el continuo lingüístico andalusí 143 PEDRO J. PLAZA GONZÁLEZ Entre la espada y la miel: tratamiento del léxico poético en la traducción de los Canti sospesi tra la terra e il cielo 155 MARGARITA PORROCHE BALLESTEROS La enseñanza de los marcadores discursivos en la clase de ELE. Los marcadores conversacionales 185 MARÍA PILAR SANCHIS CERDÁN La derivación apreciativa y la expresividad de los sufijos aumentativos: estado de la cuestión 213 GABRIEL VALLE Anglicismo y defensa de la lengua en los tiempos de las redes sociales 239 Introducción Con este volumen sexto de LEA, que recoge las publicaciones del sexto y séptimo congreso, han pasado quince años de la publicación del primero. -

A Study of Stambeli in Digital Media

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 A Study of Stambeli in Digital Media Nneka Mogbo Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, African Studies Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, Religion Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons A Study of Stambeli in Digital Media Nneka Mogbo Mounir Khélifa, Academic Director Dr. Raja Labadi, Advisor Wofford College Intercultural Studies Major Sidi Bou Saïd, Tunisia Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Tunisia and Italy: Politics and Religious Integration in the Mediterranean, SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 Abstract This research paper explores stambeli, a traditional spiritual music in Tunisia, by understanding its musical and spiritual components then identifying ways it is presented in digital media. Stambeli is shaped by pre-Islamic West African animist beliefs, spiritual healing and trances. The genre arrived in Tunisia when sub-Saharan Africans arrived in the north through slavery, migration or trade from present-day countries like Mauritania, Mali and Chad. Today, it is a geographic and cultural intersection of sub-Saharan, North and West African influences. Mogbo 2 Acknowledgements This paper would not be possible without the support of my advisor, Dr. Raja Labadi and the Spring 2019 SIT Tunisia academic staff: Mounir Khélifa, Alia Lamããne Ben Cheikh and Amina Brik. I am grateful to my host family for their hospitality and support throughout my academic semester and research period in Tunisia. I am especially grateful for my host sister, Rym Bouderbala, who helped me navigate translations. -

A Message from Afar: Fact Sheet 3 (PDF)

3 What’s the Message? Here’s your signal The detection of a signal from another world would be a most remarkable moment in human history. However, if we detect such a signal, is it just a beacon from their technology, without any content, or does it contain information or even a message? Does it resemble sound, or is it like interstellar e-mail? Can we ever understand such a message? This appears to be a tremendous challenge, given that we still have many scripts from our own antiquity that remain undeciphered, despite many serious attempts, over hundreds of years. – And we know far more about humanity than about extra-terrestrial intelligence… We are facing all the complexities involved in understanding and glimpsing the intellect of the author, while the world’s expectations demand immediacy of information. So, where do we begin? Structure and language Information stands out from randomness, it is based on structures. The problem goal we face, after we detect a signal, is to first separate out those information-carrying signals from other phenomena, without being able to engage in a dialogue, and then to learn something about the structure of their content in the passing. This means that we need a suitable filter. We need a way of separating out the interesting stuff; we need a language detector. While identifying the location of origin of a candidate signal can rule out human making, its content could involve a vast array of possible structures, some of which may be beyond our knowledge or imagination; however, for identifying intelligence that shares any pattern with our way of processing and transmitting information, the collective knowledge and examples here on Earth are a good starting point. -

Berber Etymologies in Maltese1

Berber E tymologies in Maltese 1 Lameen Souag LACITO (CNRS – Paris Sorbonne – INALCO) France ﻣﻠﺧص : ﻻ ﯾزال ﻣدى ﺗﺄﺛﯾر اﻷﻣﺎزﯾﻐﯾﺔ ﻓﻲ اﻟﻣﺎﻟطﯾﺔ ﻏﺎﻣﺿﺎ، واﻟﻛﺛﯾر ﻣن اﻻﻗﺗراﺣﺎت اﻟﻣﻧﺷورة ﻓﻲ ھذا اﻟﻣﺟﺎل ﻟﯾﺳت ﻣؤﻛدة . ھذه اﻟﻣﻘﺎﻟﺔ ﺗﻘﯾم ﻛل ﻛﻠﻣﺔ ﻣﺎﻟطﯾﺔ اﻗ ُﺗرح ﻟﮭﺎ أﺻل أﻣﺎزﯾﻐﻲ ﻣن ﻗﺑل، ﻓﺗﺳﺗﺑﻌد ﺧﻣﺳﯾن ﻛﻠﻣﺔ وﺗﻘﺑل ﻋﺷرﯾن . ﻛﻣﺎ أﻧﮭﺎ ﺗﻘﺗرح ﻟﻠﻣرة اﻷوﻟﻰ أﺻوﻻ أﻣﺎزﯾﻐﯾﺔ ﻟﺳﺗﺔ ﻛﻠﻣﺎت ﻣﺎﻟطﯾﺔ ﻏﯾر ھذه اﻟﺳﺑﻌﯾن، وھﻲ " أﻛﻠﺔ ﻟزﺟﺔ " ، " ﺻﻐﯾر " ، " طﯾر اﻟوﻗواق " ، " ﻧﺑﺎت اﻟدﯾس " ، " أﻧﺛﻰ اﻟﺣﺑ ﺎر " ، واﻟﺗﺻﻐﯾر ﺑﻌﻼﻣﺔ اﻟﺗﺄﻧﯾث . ﺑﻧﺎء ﻋﻠﻰ ھذه اﻟﻧﺗﺎﺋﺞ، ﺗﻔﺣص اﻟﻣﻘﺎﻟﺔ اﻟﺗوزﯾﻊ اﻟدﻻﻟﻲ ﻟدى اﻟﻣﻔردات اﻟدﺧﯾﻠﺔ ﻣن اﻷﻣﺎزﯾﻐﯾﺔ ﻟﺗﻠﻘﻲ ﻧظرة ﻋﻠﻰ ﻧوﻋﯾﺔ اﻻﺣﺗﻛﺎك ﺑﯾن اﻟﻌرﺑﯾﺔ واﻷﻣﺎزﯾﻐﯾﺔ ﻓﻲ إﻓرﯾﻘﯾﺔ ﻗﺑل وﺻول ﺑﻧﻲ ھﻼل إﻟﻰ اﻟﻣﻧطﻘﺔ Abstract : The extent of Berber lexical influence on Maltese remains unclear, and many of the published etymological proposals are problematic. This article evaluates the reliability of existing proposed Maltese etymologies involving Berber, excluding 50 but accepting 20, and proposes new Berbe r etymologies for another six Maltese words ( bażina “overcooked, sticky food”, ċkejken “small”, daqquqa “cuckoo”, dis “dis - grass, sparto”, tmilla “female cuttlefish used as bait”), as well as a diminutive formation strategy using - a . Based on the results, it examines the distribution of the loans found, in the hope of casting light on the context of Arabic - Berber contact in Ifrīqiyah before the arrival of the Banū Hilāl. Keywords: Maltese, Berber, Amazigh, etymology, loanword s 1 The author thanks Marijn van Putten, Karim Bensoukas, and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper, and Abdessalem Saied for providing Nabuel data. © The International Journal of Arabic Linguistics (IJAL) Vol. -

The Festive Sacred and the Fetish of Trance Performing the Sacred at the Essaouira Gnawa Festival Le Sacré Festif Et La Transe Fétiche

Gradhiva Revue d'anthropologie et d'histoire des arts 7 | 2008 Le possédé spectaculaire The Festive Sacred and the Fetish of Trance Performing the Sacred at the Essaouira Gnawa Festival Le sacré festif et la transe fétiche. La performance du sacré au festival gnaoua et musiques du monde d’Essaouira Deborah Kapchan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/gradhiva/1014 DOI: 10.4000/gradhiva.1014 ISSN: 1760-849X Publisher Musée du quai Branly Jacques Chirac Printed version Date of publication: 15 May 2008 Number of pages: 52-67 ISBN: 978-2-915133-86-8 ISSN: 0764-8928 Electronic reference Deborah Kapchan, « The Festive Sacred and the Fetish of Trance », Gradhiva [Online], 7 | 2008, Online since 15 May 2011, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/gradhiva/1014 ; DOI : 10.4000/gradhiva.1014 © musée du quai Branly Fig. 1 Spectacle gnawa au « festival gnaoua et musiques du monde d’Essaouira », 24 juin 2006. © Pierre-Emmanuel Rastoin (P. E. R.). Dossier The Festive Sacred and the Fetish of Trance Performing the Sacred at the Essaouira Gnawa Festival of World Music Deborah Kapchan t is late June 1999 and I am in Essaouira, Morocco, it still unfolds b-haqq-u u treq-u, in its truth and its path. for the Essaouira Gnawa Festival of World Music. In 2004 I find myself in Essaouira again. There is ano- I The weather is balmy, but the wind of this coastal ther conference — this time on religion and slavery — city blows so hard that the festival-goers clasp their organized by another scholar, historian Mohammed scarves tightly around them. -

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

1 Khal: An Exploration of the Language around Blackness in Morocco Rachel Leigh Johnson Independent Study Project SIT Morocco: Fall 2007 Advisor: Yamina El-Kirat 2 Table of Contents Introduction Purpose and Thesis 1 Methodology 2 Complications, Ethics and Future Research 3 Chapter 1: Azzi 7 Chapter 2: Abd 12 Chapter 3: Khal 18 Conclusion 27 3 Introduction The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (Sapir, 1921; Whorf, 1956) is perhaps the most well known and the most provocative conjecture about the relationship between language and thought. According to the theory, speakers … are locked into the world view given to them by their language: ` The "real world" is to a large extent unconsciously built on the language habits of the group' (Sapir, 1951 [1929])…[and] colour language can affect colour cognition. (Davies et al 1) Purpose and Thesis Morocco has been described as a melting pot. While various ethnicities, religious beliefs, and languages merge and intermingle within the country, the language in the majority of Moroccan homes is Darijaa. The language itself is a mixture of the Amazigh language and classical and popular Arabic with some European elements. Additionally, Darijaa is the language through which the majority of Moroccans have come to understand the world and the people around them. It is also through this language that I will explore conceptions of blackness and black identity in Morocco. Through evaluating the words for “black” in Darijaa, I hope to reveal the ways in which language may affect social constructions of a black identity in Morocco. My interest in this project stems from my experiences walking the streets of Morocco.