The Relationship of Esotericism and Egyptology, 1875-1930

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prayer – Seeing Things from God's Perspective I Like Flying (In a Plane

Prayer – Seeing Things from God’s Perspective I like flying (in a plane, of course). It gives me a new perspective. From thousands of feet up I can see snow-capped mountains, arid deserts dissected by dry watercourses, cultivated fields in neat rows, meandering rivers, busy highways, rugged coastlines, clouds, beautiful sunrises and sunsets, and occasionally other aircraft. I have flown on and off most of my adult life and, with a few exceptions, have enjoyed it. But from time to time I think about where I am. From the relative comfort (never easy because I have long legs) of a spacious wide-body jet, watching a recent movie or interpreting airline food, it is easy to think that we and our fellow-passengers are alone, safe and in a “big space”. It is easy to forget that, from 40,000 feet, the reason the landscape below seems so small is that we are a long way above the surface of the earth. From the vantage point of someone on the ground looking up at the jet passing overhead, we are a long way up, and the aircraft looks very, very small in a huge expanse of nothing. We are vulnerable, to the elements, the reliability of the plane and the potential for mechanical or pilot error. We make an assumption that we will reach our destination, and forget that such a conclusion is only our perspective, which may turn out not to be correct after all. Witness the recent disappearance and protracted search for Malaysia Airlines flight 370. When there is turbulence, our perspective can change quickly; we recall airline accidents attributed to clear air turbulence, severe tropical storms, lightning (I have been in a plane struck by lightning, when the electrical systems appeared to fail, for a few long seconds) or engine problems. -

Copyright - for the Thelemites

COPYRIGHT - FOR THE THELEMITES Downloaded from https://www.forthethelemites.website You may quote from this PDF file in printed and digital publications as long as you state the source. Copyright © Perdurabo ST, 2017 E.V. FOR THE COPYRIGHTTHELEMITES - FOR THE THELEMITES ROSE AND ALEISTER CROWLEY’S STAY IN EGYPT IN 1904 A STUDY OF THE CAIRO WORKING AND WHAT IT LED TO BY PERDURABO ST ã FRATER PERDURABO, to whom this revelation was made with so many signs and wonders, was himself unconvinced. He struggled against it for years. Not until the completion of His own initiation at the end of 1909 did He understand how perfectly He was bound to carry out this work. (Indeed, it was not until his word became conterminous with Himself and His Universe that all alien ideas lost their meaning for him). Again and again He turned away from it, took it up for a few days or hours, then laid it aside. He even attempted to destroy its value, to nullify the result. Again and again the unsleeping might of the Watchers drove Him back to the work; and it was at the very moment when He thought Himself to have escaped that He found Himself fixed for ever with no possibility of again turning aside for the fraction of a second from the path. The history of this must one day be told by a more vivid voice. Properly considered, it is a history of continuous miracle. THE EQUINOX OF THE GODS, 1936 E.V. For the Thelemites CHAPTER 6 Ì[Htp (hetep), altar] • The replica As regards the replica, which Crowley later published as a photographical colour reproduction in both TSK1912 and EG873, who was the artist? As seen above, Crowley writes in Confessions that it was a replica madeCOPYRIGHT by one of the artists attached - FOR to the THE museu m.THELEMITES.874 In fact there was an artist on the permanent staff of the museum as stated in various records. -

Israel Regardie and the Psychologization of Esoteric Discourse

Correspondences 3 (2015) 5–54 ISSN: 2053-7158 (Online) correspondencesjournal.com Israel Regardie and the Psychologization of Esoteric Discourse Christopher A. Plaisance E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This is an article in the history of Western esoteric currents that re-examines and clarifies the relationship between esoteric and psychological discourses within the works of Israel Regardie. One of the most common ways in which these two discourses have been found to be related to one another by scholars of the esoteric is through the process of “psychologization”— with Regardie often being put forth as a paragon of the process. This paper argues that a unitary conception of psychologization fails to adequately describe the specific discursive strategies utilized by Regardie. In order to accurately analyze his ideas, a manifold typology of complementary, terminological, reductive, and idealist modes of psychologization is proposed instead. Through this system of classification, Regardie’s ideas regarding the relationship between psychological and esoteric discourses are understood as a network of independent but non-exclusive processes, rather than as a single trend. It is found that all four modes of psychologization are present, both in relative isolation and in combination with one another, throughout his works. These results demonstrate that while it is accurate to speak of Regardie as having psychologized esoteric discourse, this can only be the case given an understanding of “psychologization” that is differentially nuanced in a way that, at least, accounts for the distinct discursive strategies this paper identifies. Keywords psychologization; method and theory; psychology and esotericism; science and religion; Israel Regardie; Golden Dawn © 2015 Christopher A. -

The Prayer of Surrender

THE PRAYER OF SURRENDER I was scheduled to fly from Philadelphia to Pittsburg this week to do a television show. On a good day it takes me about 80 minutes to drive to the Philadelphia airport from my house. Snow flurries were forecast for Tuesday but they weren’t supposed to last. But they did and got heavier and heavier as the morning wore on. I began to worry. I have a disease my children have dubbed, “Worst Case Scenario Disease.” Perhaps you have it too. My mind began imagining the worst things that might happen while I was driving to the airport in the snow. For example, I might miss my plane or it would be cancelled and I wouldn’t be able to get to the television show. Or, I might get in a terrible accident and never make my plane. Or, the plane would crash because the wings got icy. Crazy, I know, but I’m just being real. But the good news is, I have learned how to get myself out of such emotional quicksand and I want to teach you how too. It’s called the prayer of surrender. We all have many desires – good and legitimate desires, nothing God would disapprove of. But what starts to happen to us when our desires get delayed, frustrated or denied? My desire in that moment was to get to the airport, make my plane and fulfill my responsibilities to be on that television show. Perhaps your desire is to have a stress free Christmas, a nice family dinner, a spouse that loves you, children who obey you, and a paycheck that supports your financial obligations. -

Freud and Egypt: Between Oedipus and the Sphinx

Freud and Egypt: Between Oedipus and the Sphinx Abstracts Simon Goldhill (University of Cambridge) Digging the Dirt: Freud's archaeology and the lure of Egypt Freud's obsession with archaeology is well-known. How should we understand this foundational metaphor for the psychoanalytical process through the contrasting cases of Greece -- ever the origin and base of Western culture for 19th-century thinking -- and Egypt -- repeatedly troped as mysterious, ancient and other? Daniel Orrells (Kings College London) Freud and Leonardo in Egypt The nineteenth-century fascination with ancient Greece provided a language to explore the complexities of modern sexual identity seemingly in all its varied forms. Freud's turn to Oedipus was part of this cultural moment. Homeric epic, Greek lyric poetry, Plato's dialogues and the body beautiful of Greek sculpture all offered different vocabularies for talking about same-sex desire. But when Freud sought to understand Leonardo's homosexuality, he turned away from Greece to an Egyptian mother goddess. This talk explores what was at stake in Freud finding Leonardo in ancient Egypt. Phiroze Vasunia (UCL) Egyptomania before Freud The fascination with ancient Egypt extends from the Bible and the Greeks and Romans into the modern period. What are the main features of this Egyptomania and how do they contribute to Freud’s interest in Egypt? We look at a few significant moments in the history of Egyptomania and discuss their significance for Freud and his thought. Claus Jurman (University of Birmingham) Freud’s Egypt – Freud’s Egyptology: A look at early 20th century Egyptology in Vienna and beyond This presentation will provide an overview of the development of Egyptology in Vienna during the first decades of the 20th century and introduce some its key figures such as Hermann Junker of the University of Vienna and Hans Demel of the Kunsthistorische Museum. -

The King Baudouin Foundation in Figures Working Together for a Better Society

Autumn 2017 The Balkans Empowering young leaders and academics Under the Honorary Chairmanship of HM Queen Mathilde www.kbs-frb.be Brussels X, P309439 Editorial Table of contents 2 Editorial Luc Tayart de Borms 3 10 years old: European Fund > Managing Director for the Balkans 4-5 Balkans focus: training young academics 6-7 Progress on cystic fibrosis: Foreword the Forton Fund 8-9 A new life for undiscovered music Welcome to the autumn edition of “shrinking space of civil society in Europe” with the Leuven Chansonnier the International Newsletter. These are and support those trying to “increase 10-11 Boosting young people’s talents precarious times for democracy with the quality of information in the public 12-13 Access to water : the Elisabeth politicians around the world accusing discourse”. We look forward to sharing and Amélie Fund each other of endangering the regular updates with you about the work 14-15 What drives Belgian academics? foundations of modern society of this Fund. and people openly expressing their 16-17 Valuing the work of a Belgian Egyptologist: the Jean Capart Fund discontent with these democratically The refugee crisis, and Europe’s apparent elected leaders. The King Baudouin inability to deal with it, is one of the stress 18-19 What Europeans think about the EU (A Chatham House study) Foundation believes deeply in supporting points that has led people to doubt the work that attempts to understand the ability of politicians. In the Newsletter 20-21 KBFUS already 20 years old; reasons for this unhappiness and many you can read about some of the work KBF Canada starts articles in this edition of the Newsletter we are supporting in this area, including 22-23 Sport and society: the Nike Community showcase this approach. -

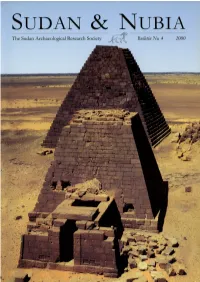

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

The Magician's Kabbalah

The Magician's Kabbalah By FP The Classical esoteric model of the Universe as practised by a working Magician, with unique details of the theories and practices of modern magic for the general reader. This book demonstrates the integration of Kabbalah with the leading edge of scientific thought in the realms of psychology and cosmology, as well as providing an unparalleled guide to the hidden world of the modern occultist. Acknowledgements I acknowledge the lessons of my teachers and colleagues of the Invisible College, particularly Frater Daleth for the Operation of Sol; Soror Jasinth for love and company in the Circle of the Moon ; Soror Brina for reopening Eden; And the participants in the Illuminated Congregation of Melchizedek, past, present and future, who seek to maintain and preserve the Greatest Work of All. Propositum Perfectio Est F.I.A.T. (5=6) Cognitatione sui secumque colloquio firmitatem petere (6=5) Dedications To Sue, whose friendship was given through a long dark night of the soul. To Carolyne. With love CONTENTS Chapter One : The Tree of Sapphires Chapter Two : The Sephiroth and the Four Worlds Chapter Three Ain Soph Aur Chapter Four : Kether Chapter Five : Chockmah Chapter Six Binah Chapter Seven Chesed Chapter Eight Geburah Chapter Nine Tiphareth Chapter Ten Netzach Chapter Eleven Hod Chapter Twelve Yesod Chapter Thirteen Malkuth Chapter Fourteen The Klippoth Chapter Fifteen Gematria Chapter Sixteen The Twenty-Two Paths Chapter Seventeen The Curtain of Souls Chapter Eighteen Exercises Chapter Nineteen The Rituals of the Sapphire Temple Appendix One Names of the Sephiroth Appendix Two The Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram Chapter Notes Bibliography Index Chapter One; The Tree of Sapphires Voices of the Word, Leaves of the Light The Kabbalah (a Hebrew word meaning "handed down", or "oral tradition") is the term used to denote a general set of esoteric or mystical teachings originally held within Judaism, but later promulgated to a wider audience in the 12th century onwards through centres of learning such as Spain. -

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional Sections Contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional sections contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D. Ph.D. Introduction Nichole Yalsovac Prophetic revelation, or Divination, dates back to the earliest known times of human existence. The oldest of all Chinese texts, the I Ching, is a divination system older than recorded history. James Legge says in his translation of I Ching: Book Of Changes (1996), “The desire to seek answers and to predict the future is as old as civilization itself.” Mankind has always had a desire to know what the future holds. Evidence shows that methods of divination, also known as fortune telling, were used by the ancient Egyptians, Chinese, Babylonians and the Sumerians (who resided in what is now Iraq) as early as six‐thousand years ago. Divination was originally a device of royalty and has often been an essential part of religion and medicine. Significant leaders and royalty often employed priests, doctors, soothsayers and astrologers as advisers and consultants on what the future held. Every civilization has held a belief in at least some type of divination. The point of divination in the ancient world was to ascertain the will of the gods. In fact, divination is so called because it is assumed to be a gift of the divine, a gift from the gods. This gift of obtaining knowledge of the unknown uses a wide range of tools and an enormous variety of techniques, as we will see in this course. No matter which method is used, the most imperative aspect is the interpretation and presentation of what is seen. -

The New Age Under Orage

THE NEW AGE UNDER ORAGE CHAPTERS IN ENGLISH CULTURAL HISTORY by WALLACE MARTIN MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS BARNES & NOBLE, INC., NEW YORK Frontispiece A. R. ORAGE © 1967 Wallace Martin All rights reserved MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 316-324 Oxford Road, Manchester 13, England U.S.A. BARNES & NOBLE, INC. 105 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003 Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd, Frome and London This digital edition has been produced by the Modernist Journals Project with the permission of Wallace T. Martin, granted on 28 July 1999. Users may download and reproduce any of these pages, provided that proper credit is given the author and the Project. FOR MY PARENTS CONTENTS PART ONE. ORIGINS Page I. Introduction: The New Age and its Contemporaries 1 II. The Purchase of The New Age 17 III. Orage’s Editorial Methods 32 PART TWO. ‘THE NEW AGE’, 1908-1910: LITERARY REALISM AND THE SOCIAL REVOLUTION IV. The ‘New Drama’ 61 V. The Realistic Novel 81 VI. The Rejection of Realism 108 PART THREE. 1911-1914: NEW DIRECTIONS VII. Contributors and Contents 120 VIII. The Cultural Awakening 128 IX. The Origins of Imagism 145 X. Other Movements 182 PART FOUR. 1915-1918: THE SEARCH FOR VALUES XI. Guild Socialism 193 XII. A Conservative Philosophy 212 XIII. Orage’s Literary Criticism 235 PART FIVE. 1919-1922: SOCIAL CREDIT AND MYSTICISM XIV. The Economic Crisis 266 XV. Orage’s Religious Quest 284 Appendix: Contributors to The New Age 295 Index 297 vii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS A. R. Orage Frontispiece 1 * Tom Titt: Mr G. Bernard Shaw 25 2 * Tom Titt: Mr G. -

Aleister Crowley's Illustrated Goetia

(}rIIEl{ TITLES FROM NEW FALCON PUBLICATIONS ( '0.\'111ic Trigger: Final Secret ofthe Illuminati Afeister Crowfey)s Prometheus Rising By Robert Anton Wilson Undoing Yourself With Energized Meditation The Psychopath's Bible I[[ustratecf Goetia: By Christopher S. Hyatt, Ph.D. Gems From the Equinox The Pathworkings ofAleister Crowley sexuaL Evocation By Aleister Crowley Info-Psychology The Game ofLife By Timothy Leary, Ph.D. By Sparks From the Fire ofTime By Rick & Louisa Clerici Lon Mifo DuQuette and Condensed Chaos: An Introduction to Chaos Magick By Phil Hine Christopfier S. Hyatt} ph.D. The Challenge ofthe New Millennium By Jerral Hicks, Ed.D. The Complete Golden Dawn System ofMagic The Golden Dawn Tapes-Series I, II, and III By Israel Regardie I[[ustratecC By Buddhism and Jungian Psychology By J. Marvin Spiegelman, Ph.D. David P. Wifson The Eyes ofthe Sun: Astrology in Light ofPsychology By Peter Malsin Metaskills: The Spiritual Art ofTherapy By Amy Mindell, Ph.D. Beyond Duality: The Art ofTranscendence By Laurence Galian Virus: The Alien Strain By David Jay Brown The Montauk Files: Unearthing the Phoenix Conspiracy By K.B. Wells Phenomenal Women: That's Us! By Dr. Madeleine Singer Fuzzy Sets By Constantin Negoita, Ph.D. And to get your free catalog of all of our titles, write to: New Falcon Publications (Catalog Dept.) 1739 East Broadway Road, #1 PMB 277 Tempe, Arizona 85282 U.S.A NEW FALCON PUBLICATIONS And visit our website at http://www.newfalcon.com TEMPE, ARIZONA, U.S.A. Copyright © 1992 V.S.E.S.S. All rights reserved. No part of this book, in part or in whole, may be reproduced, transmitted, or utilized, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, record ing, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except for brief quota tions in critical articles, books and reviews. -

Relations in the Humanities Between Germany and Egypt

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg HANS ROBERT ROEMER Relations in the humanities between Germany and Egypt On the occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907 – 1982) Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Ägypten, Dauer und Wandel : Symposium anlässlich d. 75jährigen Bestehens d. Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Kairo. Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern, 1985, S.1 - 6 Relations in the Humanities between Germany and Egypt On the Occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907-1982) by HANS ROBERT ROEMER I The nucleus of the Institute whose jubilee we are celebrating today was established in Cairo in 1907 as »The Imperial German Institute for Egyptian Archaeology«. This was the result of a proposal presented by the Berlin Egyptologist Adolf Erman on behalf of the commission for the Egyptian Dictionary, formed by the German Academies of Sciences. This establishment had its antecedents in the 19th century, whose achievements were not only incomparable developments in the natural sciences, but also an unprecedented rise in the Humanities, a field in which German Egyptologists had contributed a substantial share. It is hence no exaggeration to consider the Institute the crowning and the climax of the excavation and research work accomplished earlier in this country. As a background, the German-Egyptian relations in the field of Humanities had already had a flourishing tradition. They had been inaugurated by Karl Richard Lepsius (1810-84) with a unique scientific work, completed in 1859, namely the publication of his huge twelve-volume book »Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Nubien« (»Monuments from Egypt and Nubia«), devoted to the results of a four-year expedition that he had undertaken.