Open Final Thesis Document.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three “Italian” Graffiti from Semna and Begrawiya North

Eugenio Fantusati THREE “ITALIAN” GRAFFITI FROM SEMNA AND BEGRAWIYA NORTH Egyptian monuments are known to bear texts and composed of soldiers, explorers, merchants and, signatures engraved by Western travelers who in the second wave clerics, was quite consider- thus left traces of their passage on walls, columns able. For a long time the call of the exotic and of and statues beginning after the Napoleonic ex- adventure drew many Italians to Africa. In the pedition. early 19th century, they had no qualms about Sudan, although less frequented, did not leaving a fragmented country, not only governed escape this certainly depreciable practice. Indeed, by foreign powers, but also the theatre of bloody none of the European explorers in Batn el-Hagar wars for independence. Their presence in Africa avoided the temptation to leave graffiti on grew progressively to such an extent that Italian, archaeological sites, as if there was some myster- taught in Khartoum’s missionary schools, became ious force pushing them to this act, undeniable the commercial language of the Sudan. For a long because visible, once they had reached their so time, it was employed both in the official docu- longed-for destination. ments of the local Austrian consulate and in the Even George Alexander Hoskins, antiquarian, Egyptian postal service before being definitely writer and excellent draftsman, who openly supplanted by French after the opening of the condemned the diffusion of the practice to deface Suez Canal (Romanato 1998: 289). monuments, admitted his own “guilt” in this Naturally, the many Italians visiting archae- respect: “I confess on my first visit to the Nile, ological sites in Nubia did not refrain from I wrote my name on one of the colossal statues in leaving graffiti just like the other Europeans. -

The Semna South Project Louis V

oi.uchicago.edu The Semna South Project Louis V. Zabkar For those who have never visited the area of southern Egypt and northern Sudan submerged by the waters of the new Assuan High Dam, and who perhaps find it difficult to visualize what the "lake" created by the new Dam looks like, we include in this report two photographs which show the drastic geographic change which oc curred in a particular sector of the Nile Valley in the region of the Second Cataract. Before the flooding one could see the Twelfth Dynasty fortress; and, next to it, at the right, an extensive predominantly Meroitic and X-Group cemetery; the characteristic landmark of Semna South, the "Kenissa," or "Church," with its domed roof, built later on within the walls of the pharaonic fortress; the massive mud-brick walls of the fortress; and four large dumps left by the excavators—all this can be seen in the photo taken at the end of our excavations in April, 1968. On our visit there in April, 1971, the fortress was completely sub merged, the mud-brick "Kenissa" with its dome having collapsed soon after the waters began pounding against its walls. One can see black spots in the midst of the waters off the center which are the stones on the top of the submerged outer wall of the fortress. The vast cemetery is completely under water. In the distance, to the north, one can clearly see the fortress of Semna West, the glacis of which is also sub- 41 oi.uchicago.edu The area of Semna South included in our concession The Semna South concession submerged by the waters of the "lake 42 oi.uchicago.edu merged, and the brick walls of which may soon collapse through the action of the risen waters. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

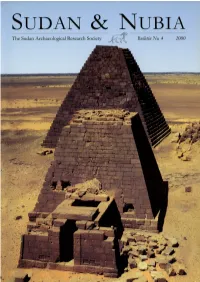

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Relations in the Humanities Between Germany and Egypt

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg HANS ROBERT ROEMER Relations in the humanities between Germany and Egypt On the occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907 – 1982) Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Ägypten, Dauer und Wandel : Symposium anlässlich d. 75jährigen Bestehens d. Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Kairo. Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern, 1985, S.1 - 6 Relations in the Humanities between Germany and Egypt On the Occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907-1982) by HANS ROBERT ROEMER I The nucleus of the Institute whose jubilee we are celebrating today was established in Cairo in 1907 as »The Imperial German Institute for Egyptian Archaeology«. This was the result of a proposal presented by the Berlin Egyptologist Adolf Erman on behalf of the commission for the Egyptian Dictionary, formed by the German Academies of Sciences. This establishment had its antecedents in the 19th century, whose achievements were not only incomparable developments in the natural sciences, but also an unprecedented rise in the Humanities, a field in which German Egyptologists had contributed a substantial share. It is hence no exaggeration to consider the Institute the crowning and the climax of the excavation and research work accomplished earlier in this country. As a background, the German-Egyptian relations in the field of Humanities had already had a flourishing tradition. They had been inaugurated by Karl Richard Lepsius (1810-84) with a unique scientific work, completed in 1859, namely the publication of his huge twelve-volume book »Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Nubien« (»Monuments from Egypt and Nubia«), devoted to the results of a four-year expedition that he had undertaken. -

The Writing of the Birds. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Before and After the Founding of Alexandria1

The Writing of the Birds. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Before and After the Founding of Alexandria1 Stephen Quirke, UCL Institute of Archaeology Abstract As Okasha El Daly has highlighted, qalam al-Tuyur “script of the birds” is one of the Arabic names used by the writers of the Ayyubid period and earlier to describe ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. The name may reflect the regular choice of Nile birds as signs for several consonants in the Ancient Egyptian language, such as the owl for “m”. However, the term also finds an ancestor in a rarer practice of hieroglyph users centuries earlier. From the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods and before, cursive manuscripts have preserved a list of sounds in the ancient Egyptian language, in the sequence used for the alphabet in South Arabian scripts known in Arabia before Arabic. The first “letter” in the hieroglyphic version is the ibis, the bird of Thoth, that is, of knowledge, wisdom and writing. In this paper I consider the research of recent decades into the Arabian connections to this “bird alphabet”. 1. Egyptological sources beyond traditional Egyptology Whether in our first year at school, or in our last year of university teaching, as life-long learners we engage with both empirical details, and frameworks of thought. In the history of ideas, we might borrow the names “philology” for the attentive study of the details, and “philosophy” for traditions of theoretical thinking.2As the classical Arabic tradition demonstrates in the wide scope of its enquiry and of its output, the quest for knowledge must combine both directions of research in order to move forward. -

"Excavating the Old Kingdom. the Giza Necropolis and Other Mastaba

EGYPTIAN ART IN THE AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK This volume has been published in "lIljunction All ri~llIs r,'slTv"d, N"l'art 01 Ihis l'ul>li,';\II"n Tl'.ul,,,,,i,,,,, f... "u the I'r,'u,'h by .I;\nl<" 1'. AlIl'll with the exhibition «Egyptian Art in the Age of may be reproduced llI' ',",lIlsmilt"" by any '"l';\nS, of "'''Iys I>y Nadine (:I",rpion allll,kan-Philippe the Pyramids," organized by The Metropolitan electronic or mechanical, induding phorocopyin~, I,auer; by .Iohu Md )on;\ld of essays by Nicolas Museum of Art, New York; the Reunion des recording, or information retrieval system, with Grima I, Audran I."brousse, .lean I.eclam, and musees nationaux, Paris; and the Royal Ontario out permission from the publishers. Christiane Ziegler; hy .lane Marie Todd and Museum, Toronto, and held at the Gaieries Catharine H. Roehrig of entries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, from April 6 John P. O'Neill, Editor in Chief to July 12, 1999; The Metropolitan Museum of Carol Fuerstein, Editor, with the assistance of Maps adapted by Emsworth Design, Inc., from Art, New York, from September 16,1999, to Ellyn Childs Allison, Margaret Donovan, and Ziegler 1997a, pp. 18, 19 January 9, 2000; and the Royal Ontario Museum, Kathleen Howard Toronto, from February 13 to May 22, 2000. Patrick Seymour, Designer, after an original con Jacket/cover illustration: Detail, cat. no. 67, cept by Bruce Campbell King Menkaure and a Queen Gwen Roginsky and Hsiao-ning Tu, Production Frontispiece: Detail, cat. -

Bulletin De L'institut Français D'archéologie Orientale

MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE BULLETIN DE L’INSTITUT FRANÇAIS D’ARCHÉOLOGIE ORIENTALE en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne BIFAO 114 (2014), p. 455-518 Nico Staring The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara Conditions d’utilisation L’utilisation du contenu de ce site est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Toute autre utilisation du site et de son contenu est soumise à une autorisation préalable de l’éditeur (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). Le copyright est conservé par l’éditeur (Ifao). Conditions of Use You may use content in this website only for your personal, noncommercial use. Any further use of this website and its content is forbidden, unless you have obtained prior permission from the publisher (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). The copyright is retained by the publisher (Ifao). Dernières publications 9782724708288 BIFAO 121 9782724708424 Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l'étranger (BAEFE) 9782724707878 Questionner le sphinx Philippe Collombert (éd.), Laurent Coulon (éd.), Ivan Guermeur (éd.), Christophe Thiers (éd.) 9782724708295 Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 30 Sylvie Marchand (éd.) 9782724708356 Dendara. La Porte d'Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724707953 Dendara. La Porte d’Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724708394 Dendara. La Porte d'Hathor Sylvie Cauville 9782724708011 MIDEO 36 Emmanuel Pisani (éd.), Dennis Halft (éd.) © Institut français d’archéologie orientale - Le Caire Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 1 / 1 The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara nico staring* Introduction In 2005 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acquired a photograph taken by French Egyptologist Théodule Devéria (fig. -

3 the Kingdom of Kush. Urban Defences and Military Installations

In : N. Crummy (ed.), Image, Craft and the Classical World. Essays in honour of Donald Bailey and Catherine Johns (Monogr. Instrumentum 29), Montagnac 2005, p. 39-54. 3 The Kingdom of Kush. Urban defences and military installations by Derek A. Welsby1 When the Romans took control of Egypt in 30 BC they with the rise of Aksum and the possible invasion of the came in direct contact on their southern frontier with the region around Meroe by the army of Aezanes (cf. Behrens Kingdom of Kush, the longest established state of any that 1986; Török 1997a, 483-4). they faced. Kush had been a major power at least since the Perhaps of more long-term concern were the low level mid 8th century BC at a time when Rome itself consisted raids mounted by the desert tribes on the fringes of the of little more than a group of huts on the Palatine. In the Nile Valley2. At least one of these incursions, during the th later 8 century BC the Kings of Kush ruled an empire reign of King Nastasen in the later 4th century BC, stretching from Central Sudan to the borders of Palestine resulted in the looting of a temple at Kawa in the Dongola controlling Egypt as pharaohs of what became known as Reach and earlier Meroe itself, the main political centre, th the 25 Dynasty. Forced to withdraw from Egypt in the seems to have been under threat. face of Assyrian aggression by the mid 7th century BC, they retreated south of the First Cataract of the Nile where they maintained control of the river valley far upstream of Urban defences the confluence of the White and Blue Niles at modern-day Khartoum, into the 4th century AD (Fig. -

Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964)

Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964) Lake Nasser, Lower Nubia: photography by the author Degree project in Egyptology/Examensarbete i Egyptologi Carolin Johansson February 2014 Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University Examinator: Dr. Sami Uljas Supervisors: Prof. Irmgard Hein & Dr. Daniel Löwenborg Author: Carolin Johansson, 2014 Svensk titel: Digital rekonstruktion av det arkeologiska landskapet i koncessionsområdet tillhörande den Samnordiska Expeditionen till Sudanska Nubien (1960–1964) English title: Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964) A Magister thesis in Egyptology, Uppsala University Keywords: Nubia, Geographical Information System (GIS), Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (SJE), digitalisation, digital elevation model. Carolin Johansson, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University, Box 626 SE-75126 Uppsala, Sweden. Abstract The Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (SJE) was one of the substantial contributions of crucial salvage archaeology within the International Nubian Campaign which was pursued in conjunction with the building of the High Dam at Aswan in the early 1960’s. A large quantity of archaeological data was collected by the SJE in a continuous area of northernmost Sudan and published during the subsequent decades. The present study aimed at transferring the geographical aspects of that data into a digital format thus enabling spatial enquires on the archaeological information to be performed in a computerised manner within a geographical information system (GIS). The landscape of the concession area, which is now completely submerged by the water masses of Lake Nasser, was digitally reconstructed in order to approximate the physical environment which the human societies of ancient Nubia inhabited. -

Archaeology on Egypt's Edge

doi: 10.2143/AWE.12.0.2994445 AWE 12 (2013) 117-156 ARCHAEOLOGY ON EGYPT’S EDGE: ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN THE DAKHLEH OASIS, 1819–1977 ANNA LUCILLE BOOZER Abstract This article provides the first substantial survey of early archaeological research in Egypt’s Dakhleh Oasis. In addition to providing a much-needed survey of research, this study embeds Dakhleh’s regional research history within a broader archaeological research framework. Moreover, it explores the impact of contemporaneous historical events in Egypt and Europe upon the development of archaeology in Dakhleh. This contextualised approach allows us to trace influences upon past research trends and their impacts upon current research and approaches, as well as suggest directions for future research. Introduction This article explores the early archaeological research in Egypt’s Dakhleh Oasis within the framework of broad archaeological trends and contemporaneous his- torical events. Egypt’s Western Desert offered a more extreme research environ- ment than the Nile valley and, as a result, experienced a research trajectory different from and significantly later than most of Egyptian archaeology. In more recent years, the archaeology along Egypt’s fringes has provided a significant contribution to our understanding of post-Pharaonic Egypt and it is important to understand how this research developed.1 The present work recounts the his- tory of research in Egypt’s Western Desert in order to embed the regional research history of the Dakhleh Oasis within broader trends in Egyptology, archaeology and world historical events in Egypt and Europe (Figs. 1–2).2 1 In particular, the western oases have dramatically reshaped our sense of the post-Pharaonic occupation of Egypt as well as the ways in which the Roman empire interfaced with local popula- tions. -

The Egyptian Fortress on Uronarti in the Late Middle Kingdom

and omitting any later additions. As such, it would be fair to Evolving Communities: The argue that our notion of the spatial organization of these sites and the lived environment is more or less petrified at Egyptian fortress on Uronarti their moment of foundation. in the Late Middle Kingdom To start to rectify these shortcomings, we have begun a series of small, targeted excavations within the fortress; we Christian Knoblauch and Laurel Bestock are combining this new data with a reanalysis of unpub- lished field notes from the Harvard/BMFA excavations as Uronarti is an island in the Batn el-Hagar approximately 5km well as incorporating important new studies on the finds from the Egyptian Middle Kingdom border with Kush at the from that excavation, for example that on the sealings by Semna Gorge. The main cultural significance of the island Penacho (2015). The current paper demonstrates how this stems from the decision to erect a large trapezoidal mnnw modest approach can yield valuable results and contribute fortress on the highest hill of the island during the reign of to a model for the development of Uronarti and the Semna Senwosret III. Together with the contemporary fortresses at Region during the Late Middle Kingdom and early Second Semna West, Kumma, Semna South and Shalfak, Uronarti Intermediate Period. constituted just one component of an extensive fortified zone at the southern-most point of direct Egyptian control. Block III Like most of these sites (excepting Semna South), Uronarti The area selected for reinvestigation in 2015-2016 was a was excavated early in the history of Sudanese archaeology small 150m2 part of Block III (Figure 1, Plate 1) directly by the Harvard/Boston Museum of Fine Arts mission in the to the local south of the treasury/granary complex (Blocks late 1920’s (Dunham 1967; Reisner 1929; 1955; 1960; Wheeler IV-VI) (Dunham 1967, 7-8; Kemp 1986) and to the north 1931), and was long believed to have been submerged by of the building probably to be identified as the residence of Lake Nubia (Welsby 2004). -

Key Words Ancient Egypt, Enlightenment, Dictator Rule, Colonialism, Patriotism, Individualism, Middle-Ages Arab Nationalism

CONTEMPORARY LITERARY REVIEW INDIA – The journal that brings articulate writings for articulate readers. CLRI ISSN 2250-3366 eISSN 2394-6075 Western-Made Source of Naguib Mahfouz’s Pharaonic Novels by Mohamed Kamel Abdel-Daem Abstract This paper argues that the efforts and discoveries in Egyptology made by European archaeologists and historians are the main references that helped the modern Egyptian people and writers learn about the history of ancient Egypt. Naguib Mahfouz’s three novels about ancient Egypt – written in the late 1930s when Egypt was under the British occupation and the Turkish rule – unconsciously conveyed postcolonial ideas to the colonized people, i.e, surrender to Fate (the colonizer’s and dictator’s reality) (Khufu’s Wisdom), irrelevance of democratic rule, lack of centralized regime leads to conflict between two domineering authorities – religious and military (Rhadopis of Nubia), and political relief from contemporary oppression springing from nostalgic pride for forcing the invaders out (Thebes at War). The three novels foster enlightenment principles of Egyptian patriotism (rather than Middle-Ages Arab) nationalism, and this helped implement the European colonizer’s strategy: ‘diaírei kaì basíleue ’. Key words ancient Egypt, enlightenment, dictator rule, colonialism, patriotism, individualism, Middle-Ages Arab nationalism. Introduction Egypt had been one of the places that witnessed the birth of human civilization. Pharaonic culture had come to existence thousands of years before, and lasted thousands of years longer than, Western civilization. But how did we know about, and how did the modern Egyptians learn about, the history of their ancient forefathers? The answer would certainly be: “from history sourcebooks”; and these books are mainly based on information in ancient parchments, as well as paintings on ancient Egyptian monuments.