Excavating Paper Squeezes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estudos De Egiptologia Vi

ESTUDOS DE EGIPTOLOGIA VI 2ª edição SESHAT - Laboratório de Egiptologia do Museu Nacional Rio de Janeiro – Brasil 2019 SEMNA – Estudos de Egiptologia VI 2ª edição Antonio Brancaglion Junior Cintia Gama-Rolland Gisela Chapot Organizadores Seshat – Laboratório de Egiptologia do Museu Nacional/Editora Klínē Rio de Janeiro/Brasil 2019 Este trabalho está licenciado com uma Licença Creative Commons - Atribuição-Não Comercial- Compartilha Igual 4.0 Internacional. Capa: Antonio Brancaglion Jr. Diagramação e revisão: Gisela Chapot Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Ficha Catalográfica B816s BRANCAGLION Jr., Antonio. Semna – Estudos de Egiptologia VI/ Antonio Brancaglion Jr., Cintia Gama-Rolland, Gisela Chapot., (orgs.). 2ª ed. – Rio de Janeiro: Editora Klínē,2019. 179 f. Bibliografia. ISBN 978-85-66714-12-8 1. Egito antigo 2. Arqueologia 3. História 4. Coleção I. Título CDD 932 CDU 94(32) I. Título. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Museu Nacional Programa de Pós-graduação em Arqueologia CDD 932 Seshat – Laboratório de Egiptologia CDU 94(32) Quinta da Boa Vista, s/n, São Cristóvão Rio de Janeiro, RJ – CEP 20940-040 Editora Klínē 2 Sumário APRESENTAÇÃO ..................................................................................................................... 4 OLHARES SOBRE O EGITO ANTIGO: O CASO DA DANÇA DO VENTRE E SUA PROFISSIONALIZAÇÃO ........................................................................................................... 5 LUTAS DE CLASSIFICAÇÕES NO EGITO ROMANO (30 AEC - 284 EC): UMA CONTRIBUIÇÃO A PARTIR DA -

2012: Providence, Rhode Island

The 63rd Annual Meeting of the American Research Center in Egypt April 27-29, 2012 Renaissance Providence Hotel Providence, RI Photo Credits Front cover: Egyptian, Late Period, Saite, Dynasty 26 (ca. 664-525 BCE) Ritual rattle Glassy faience; h. 7 1/8 in Helen M. Danforth Acquisition Fund 1995.050 Museum of Art Rhode Island School of Design, Providence Photography by Erik Gould, courtesy of the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Photo spread pages 6-7: Conservation of Euergates Gate Photo: Owen Murray Photo page 13: The late Luigi De Cesaris conserving paintings at the Red Monastery in 2011. Luigi dedicated himself with enormous energy to the suc- cess of ARCE’s work in cultural heritage preservation. He died in Sohag on December 19, 2011. With his death, Egypt has lost a highly skilled conservator and ARCE a committed colleague as well as a devoted friend. Photo: Elizabeth Bolman Abstracts title page 14: Detail of relief on Euergates Gate at Karnak Photo: Owen Murray Some of the images used in this year’s Annual Meeting Program Booklet are taken from ARCE conservation projects in Egypt which are funded by grants from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The Chronique d’Égypte has been published annually every year since 1925 by the Association Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth. It was originally a newsletter but rapidly became an international scientific journal. In addition to articles on various aspects of Egyptology, papyrology and coptology (philology, history, archaeology and history of art), it also contains critical reviews of recently published books. -

The Work of the Theban Mapping Project by Kent Weeks Saturday, January 30, 2021

Virtual Lecture Transcript: Does the Past Have a Future? The Work of the Theban Mapping Project By Kent Weeks Saturday, January 30, 2021 David A. Anderson: Well, hello, everyone, and welcome to the third of our January public lecture series. I'm Dr. David Anderson, the vice president of the board of governors of ARCE, and I want to welcome you to a very special lecture today with Dr. Kent Weeks titled, Does the Past Have a Future: The Work of the Theban Mapping Project. This lecture is celebrating the work of the Theban Mapping Project as well as the launch of the new Theban Mapping Project website, www.thebanmappingproject.com. Before we introduce Dr. Weeks, for those of you who are new to ARCE, we are a private nonprofit organization whose mission is to support the research on all aspects of Egyptian history and culture, foster a broader knowledge about Egypt among the general public and to support American- Egyptian cultural ties. As a nonprofit, we rely on ARCE members to support our work, so I want to first give a special welcome to our ARCE members who are joining us today. If you are not already a member and are interested in becoming one, I invite you to visit our website arce.org and join online to learn more about the organization and the important work that all of our members are doing. We provide a suite of benefits to our members including private members-only lecture series. Our next members-only lecture is on February 6th at 1 p.m. -

AND8002/D Eclinps™, Eclinps Lite™, Eclinps Plus™, Eclinps MAX™, and Gigacomm™ Marking and Ordering Information Guide

查询AND8003-D供应商 捷多邦,专业PCB打样工厂,24小时加急出货 AND8002/D ECLinPS,ECLinPSLite, ECLinPSPlus, ECLinPSMAX,and GigaCommMarkingand OrderingInformationGuide http://onsemi.com APPLICATION NOTE Prepared by: Paul Shockman ON Semiconductor HFPD Applications Engineer Introduction This application note describes the device markings and This application note also includes the following ordering information for the following ON Semiconductor appendices: families (refer to the respective family data book for family • Appendix 1: ECLinPS Device Order Number and information): Marking tables. • ECLinPS • Appendix 2: ECLinPS Lite Device Order Number and • ECLinPS Lite Marking tables. • ECLinPS Plus • Appendix 3: ECLinPS Plus Device Order Number and • ECLinPS MAX Marking tables. • GigaComm • Appendix 4: ECLinPS MAX Device Order Number Note that data sheet information takes precedence over and Marking Tables. this application note if there are any differences. • Appendix 5: GigaComm Device Order Number and Marking tables. Application Note Information This application note is divided into the following sections: • Section 1: Data Sheet Marking Diagrams − The diagrams provide identification, traceability, date, and packaging information. • Section 2: Data Sheet Ordering Information Tables − The tables list the device order numbers for every available device configuration. Semiconductor Components Industries, LLC, 2005 1 Publication Order Number: April, 2005 − Rev. 6 AND8002/D AND8002/D SECTION 1: Data Sheet Marking Diagrams Device Marking Examples • Code 1. Circuit Identification Code The marking format is dependent upon the device • Code 2. Temperature Compensation Code package, and larger device packages allow the inclusion of • Code 3. Family Identification Code more information on the face of the device. On the larger • packages where marking space permits, the Pb Free Code 4. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

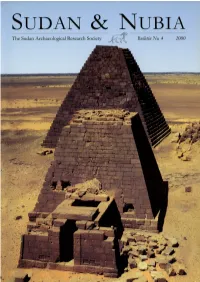

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Nilotic Livestock Transport in Ancient Egypt

NILOTIC LIVESTOCK TRANSPORT IN ANCIENT EGYPT A Thesis by MEGAN CHRISTINE HAGSETH Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Chair of Committee, Shelley Wachsmann Committee Members, Deborah Carlson Kevin Glowacki Head of Department, Cynthia Werner December 2015 Major Subject: Anthropology Copyright 2015 Megan Christine Hagseth ABSTRACT Cattle in ancient Egypt were a measure of wealth and prestige, and as such figured prominently in tomb art, inscriptions, and even literature. Elite titles and roles such as “Overseer of Cattle” were granted to high ranking officials or nobility during the New Kingdom, and large numbers of cattle were collected as tribute throughout the Pharaonic period. The movement of these animals along the Nile, whether for secular or sacred reasons, required the development of specialized vessels. The cattle ferries of ancient Egypt provide a unique opportunity to understand facets of the Egyptian maritime community. A comparison of cattle barges with other Egyptian ship types from these same periods leads to a better understand how these vessels fit into the larger maritime paradigm, and also serves to test the plausibility of aspects such as vessel size and design, composition of crew, and lading strategies. Examples of cargo vessels similar to the cattle barge have been found and excavated, such as ships from Thonis-Heracleion, Ayn Sukhna, Alexandria, and Mersa/Wadi Gawasis. This type of cross analysis allows for the tentative reconstruction of a vessel type which has not been identified previously in the archaeological record. -

In the XVIII Dynasty of Egypt – New Kingdom C. 1400 BC

Four Surveyors of the Gods: In the XVIII Dynasty of Egypt – New Kingdom c. 1400 B.C. John F. BROCK, Australia Key words: Ancient Egypt, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, Cadastre Scribes, Amenhotep-si-se, Djeserkereseneb, Khaemhat, Menna, Theban tombs. SUMMARY I have often heard it said, and even seen it written, that no one actually knows who the surveyors of ancient Egypt were ! This could not be more distant from the facts ! In reality, even though the harpedonaptae (“rope stretchers”) who were the surveyor’s assistants were not individually known, the master surveyors were not only well known but each even had his own tomb adorned with wall paintings and hieroglyphics of a biographical nature attesting to their achievements and status during their lives in the service of the King. Ironically, the four well testified Royal Surveyors, or Scribes of the Fields, as they were officially titled, are all from the Eighteenth Dynasty of the New Kingdom (around 1400 B.C.). This is the period of the ancient culture most renowned for producing such notable characters as the Thutmoses (four main ones), Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Hatshepsut, and Horemheb, the great general. It is not surprising that to this very active, and somewhat turbulent era, we can attribute the four Royal Scribe Surveyors, Amenhotep-si-se, Djeserkareseneb, Khaemhat and Menna, through whose funerary monumentation we can take a colourful and exciting trip back nearly 3500 years to experience Royal surveying – Egyptian style ! In the following paper you will meet these four surveyors, see and hear about their lives and families from their biographical tomb paintings and inscriptions, as well as finding out some more information regarding the most colourful and legendary times in which they lived, where they were interred and under whose Pharaohnic rule they worked and were buried. -

The IRBYS of LINCOLNSHIRE LINCOLNSHIRE IRBY Arl'iis the IRBYS of LINCOLNSHIRE and the IREBYS of CUMBERLAND

The IRBYS of LINCOLNSHIRE LINCOLNSHIRE IRBY ARl'IIS THE IRBYS OF LINCOLNSHIRE AND THE IREBYS OF CUMBERLAND BY PAUL AUBERT IRBY (R. 20) PART I The IRBYS of LINCOLNSHIRE Printed for Private Circulation REID BROS. LTD., 187 WARDOUR STREET, LONDON, w. I PUBLISHED MCMXXXVIII PRlNTltD BY K.IMBL't & BRADFORD, LONDON, W. 1. DEDICATED TO Members of the IRBY family in this country and overseas. FOREWORD Tms account of the IRBYS of Lincolnshire and IREBYS of Cumberland, which I have been engaged on for some years, does not pretend to be of any general interest, and is only compiled so that members of the family may have some sort of introduction to their forbears. My grateful thanks are due to the Head of the family, the sixth Baron Boston (S. 1) for the kindly interest he has taken in this production, to my brother Lewis Michael Aubert (R. 2 1 ), of Messrs. Sotheby & Co., who has pro vided me with a good deal of information about members of the family to be found in various books that have come under his survey, and to Cecil Eustace (T. 2) for a good deal of Cumberland research. I am also indebted to Miss M. K. Dale for research in the Public Record Office, more particularly in the . Cumberland portion of the book, and to "Tasmary" (T. 16), for her kind assistance in typing out most of the manuscript for me when on a visit to this country in 1936. There may be, and probably are, branches of the family in this country and possibly in Ireland, of which I have no record, as it will be seen from the Pedigree Chart 1 that in the earlier parts of the Pedigree there are a good many members of the family about whom I have been able to discover very little information, and they may of course have descendants still flourishing in some district. -

Relations in the Humanities Between Germany and Egypt

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg HANS ROBERT ROEMER Relations in the humanities between Germany and Egypt On the occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907 – 1982) Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Ägypten, Dauer und Wandel : Symposium anlässlich d. 75jährigen Bestehens d. Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Kairo. Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern, 1985, S.1 - 6 Relations in the Humanities between Germany and Egypt On the Occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907-1982) by HANS ROBERT ROEMER I The nucleus of the Institute whose jubilee we are celebrating today was established in Cairo in 1907 as »The Imperial German Institute for Egyptian Archaeology«. This was the result of a proposal presented by the Berlin Egyptologist Adolf Erman on behalf of the commission for the Egyptian Dictionary, formed by the German Academies of Sciences. This establishment had its antecedents in the 19th century, whose achievements were not only incomparable developments in the natural sciences, but also an unprecedented rise in the Humanities, a field in which German Egyptologists had contributed a substantial share. It is hence no exaggeration to consider the Institute the crowning and the climax of the excavation and research work accomplished earlier in this country. As a background, the German-Egyptian relations in the field of Humanities had already had a flourishing tradition. They had been inaugurated by Karl Richard Lepsius (1810-84) with a unique scientific work, completed in 1859, namely the publication of his huge twelve-volume book »Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Nubien« (»Monuments from Egypt and Nubia«), devoted to the results of a four-year expedition that he had undertaken. -

We're Archæologists, Not Grave Robbers!

We’re Archæologists, Not Gra ve Robbers! A Terra Incognita Ad venture, Egypt, 1908 by Ann Dupuis and Scott Larson Copyright ©2002 by Grey Ghost Press, Inc. Ancient tombs, precious artifacts, a race against time and rival archaeologists – you’ve done this before. But this time the tomb’s defenses may be your death.... But the prize, oh the prize! About Terra Incognita: Terra Incognita is a Victorian/Pulp roleplaying game from Grey Ghost Press, Inc. It follows the exploits of the National Archæological, Geographic, and Submarine Society, an organization of explorers and adventurers. The NAGS society’s public face is that of a stodgy society of would-be and have-been adventurers based in London, England. Behind the scenes, NAGS operatives from nearly every continent and culture travel to the four corners of the world, uncovering ancient mysteries and secrets. The Society studies and examines the ancient artifacts and knowledge so uncovered. If they deem the world is not yet ready for the secrets that had so long lain hidden, they cover them back up again. For more information about Terra Incognita, including pre-generated player characters that may be used with this adventure, please visit http://www.nagssociety.com. What’s Fudge? Fudge is a role-playing game for any genre, setting, or campaign. It’s designed to be modified for each Game Master’s needs and preferences. Terra Incognita uses a customized version of Fudge. You can get the full Fudge rules free on-line, at http://www.fudgerpg.com. Or buy the Fudge Expanded Edition from your Favorite Local Game Store! Backstory for "We’re Archaeologists!" Twenty years ago, in 1888, a group of Nags discovered, excavated, and explored an ancient Egyptian tomb in the Western branch of the Valley of the Kings. -

The Writing of the Birds. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Before and After the Founding of Alexandria1

The Writing of the Birds. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Before and After the Founding of Alexandria1 Stephen Quirke, UCL Institute of Archaeology Abstract As Okasha El Daly has highlighted, qalam al-Tuyur “script of the birds” is one of the Arabic names used by the writers of the Ayyubid period and earlier to describe ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. The name may reflect the regular choice of Nile birds as signs for several consonants in the Ancient Egyptian language, such as the owl for “m”. However, the term also finds an ancestor in a rarer practice of hieroglyph users centuries earlier. From the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods and before, cursive manuscripts have preserved a list of sounds in the ancient Egyptian language, in the sequence used for the alphabet in South Arabian scripts known in Arabia before Arabic. The first “letter” in the hieroglyphic version is the ibis, the bird of Thoth, that is, of knowledge, wisdom and writing. In this paper I consider the research of recent decades into the Arabian connections to this “bird alphabet”. 1. Egyptological sources beyond traditional Egyptology Whether in our first year at school, or in our last year of university teaching, as life-long learners we engage with both empirical details, and frameworks of thought. In the history of ideas, we might borrow the names “philology” for the attentive study of the details, and “philosophy” for traditions of theoretical thinking.2As the classical Arabic tradition demonstrates in the wide scope of its enquiry and of its output, the quest for knowledge must combine both directions of research in order to move forward. -

Water Quality Assessment Report for United Keno Hill Mines

WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR UNITED KENO HILL MINES Report Prepared for: Elsa Reclamation and Development Company Whitehorse, Yukon Report Prepared by: Minnow Environmental Inc. 2 Lamb Street Georgetown, Ontario L7G 3M9 July 2008 WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR UNITED KENO HILL MINES Report Prepared for: Elsa Reclamation and Development Company Whitehorse, Yukon Report Prepared by: Minnow Environmental Inc. Cynthia Russel, B.Sc. Project Manager Patti Orr, M.Sc. Technical Reviewer July 2008 ERDC Water Quality Assessment EXECUTIVE SUMMARY United Keno Hill Mines Limited and UKH Minerals Ltd. were the previous owners of the properties located on and around Galena Hill, Keno Hill, and Sourdough Hill collectively known as the United Keno Hill Mining Property (UKHM). The UKHM is located in north- central Yukon Territory and is comprised of approximately 827 mineral claims covering the three mountains (“hills” named above) over an area of approximately 15,000 ha (about 29 km long and 8 km wide). Associated with the site are abandoned adits, buildings/structures, and waste material which represent a source of contaminants to the downstream watersheds. In June 2005, Alexco Resource Corp was selected as the preferred purchaser of the UKHM assets. Alexco’s subsidiary Elsa Reclamation and Development Company (ERDC) is required to develop a Reclamation Plan for the Existing State of the Mine. As part of the closure planning process, long-term water quality performance will need to be assessed relative to relevant water uses and closure plan options. It is expected that historical sources associated with the UKHM may not allow for generic water quality guidelines to be achieved at all downstream locations and that alternative targets may need to be developed, depending on water use goals.