World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar-Government-Projects.Pdf

Planned Total Implementing Date Date Last Project Project Planned Funding Financing Tender Developer Sector Sr. Project ID Description Expected Benefits End Project Government Ministry Townships Sectors MSDP Alignment Project URL Created Modified Title Status Start Date Sources Information Date Name Categories Date Cost Agency The project will involve redevelopment of a 25.7-hectare site The project will provide a safe, efficient and around the Yangon Central Railway Station into a new central comfortable transport hub while preserving the transport hub surrounded by housing and commercial heritage value of the Yangon Central Railway Station amenities. The transport hub will blend heritage and modern and other nearby landmarks. It will be Myanmar’s first development by preserving the historic old railway station main ever transit-oriented development (TOD) – bringing building, dating back in 1954, and linking it to a new station residential, business and leisure facilities within a constructed above the rail tracks. The mixed-use development walking distance of a major transport interchange. will consist of six different zones to include a high-end Although YCR railway line have been upgraded, the commercial district, office towers, condominiums, business image and performance of existing railway stations are hotels and serviced apartments, as well as a green park and a still poor and low passenger services. For that railway museum. reason, YCR stations are needed to be designed as Yangon Circular Railway Line was established in 1954 and it has attractive, comfortable and harmonized with city been supporting forYangon City public transportation since last development. On the other hand, we also aligned the 60 years ago. -

IPNI Library As References

International Plant Nutrition Institute Regional Office • Southeast Asia Date: September 15, 2017 Page: 1 of 109 New Entries to IPNI Library as References [1] J. Hawksworth, H. Audino, R. Clarry, Secondary J. Hawksworth, H. Audino, R. Clarry. 2017. The Long View: How will the global economic order change by 2050? Page 1 - 72. Reference ID: 23486 Note: H 8.1.1.5 #23486e Abstract: After a year of major political shocks with the Brexit vote and the election of President Trump, it might seem brave to opine on economic prospects for 2017, let alone 2050. However, I still think it is important to take a longer term view of global economic prospects that looks beyond the short-term ups and downs of the economic and political cycle, which are indeed very difficult to forecast. Instead our approach in this report, based on a rigorous modelling approach, focuses on the fundamental drivers of growth: demographics and productivity, which in turn is driven by technological progress and diffused through international trade and investment. Such forces saw America progress through the 19th and early 20th centuries to become the largest economy in the world despite a civil war, various other conflicts with foreign powers, three presidential assassinations, and numerous economic and financial crises. These forces also helped global economic growth to bounce back strongly from two world wars and a Great Depression to reach record levels in the post-war decades. Looking ahead, we think they will see emerging economies come to dominate the 21st century. By 2050 we project China will be the largest economy in the world by a significant margin, while India could have edged past the US into second place and Indonesia have risen to fourth place. -

The Myanmar-Thailand Corridor 6 the Myanmar-Malaysia Corridor 16 the Myanmar-Korea Corridor 22 Migration Corridors Without Labor Attachés 25

Online Appendixes Public Disclosure Authorized Labor Mobility As a Jobs Strategy for Myanmar STRENGTHENING ACTIVE LABOR MARKET POLICIES TO ENHANCE THE BENEFITS OF MOBILITY Public Disclosure Authorized Mauro Testaverde Harry Moroz Public Disclosure Authorized Puja Dutta Public Disclosure Authorized Contents Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar 1 Appendix 2 Forms used to collect information at Labor Exchange Offices 3 Appendix 3 Registering jobseekers and vacancies at Labor Exchange Offices 5 Appendix 4 The migration process in Myanmar 6 The Myanmar-Thailand corridor 6 The Myanmar-Malaysia corridor 16 The Myanmar-Korea corridor 22 Migration corridors without labor attachés 25 Appendix 5 Obtaining an Overseas Worker Identification Card (OWIC) 29 Appendix 6 Obtaining a passport 30 Cover Photo: Somrerk Witthayanant/ Shutterstock Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar State/Region Name State/Region Name Yangon No (1) LEO Tanintharyi Dawei Township Office Yangon No (2/3) LEO Tanintharyi Myeik Township Office Yangon No (3) LEO Tanintharyi Kawthoung Township Office Yangon No (4) LEO Magway Magwe Township Office Yangon No (5) LEO Magway Minbu District Office Yangon No (6/11/12) LEO Magway Pakokku District Office Yangon No (7) LEO Magway Chauk Township Office Yangon No (8/9) LEO Magway Yenangyaung Township Office Yangon No (10) LEO Magway Aunglan Township Office Yangon Mingalardon Township Office Sagaing Sagaing District Office Yangon Shwe Pyi Thar Township Sagaing Monywa District Office Yangon Hlaing Thar Yar Township Sagaing Shwe -

The Properties and Utilization of Soilin the Greening Project for the Ninecritical Districts of the Arid Zone of Central Myanmar ( Part II )

Leaflet No. 3/1997 Government of theUnion of Myanmar Ministry of Forestry Forest Department The Properties and Utilization of Soilin the Greening Project for the NineCritical Districts of the Arid Zone of Central Myanmar ( Part II ) U Sann Lwin (2), Deputy Director, U Htin Kyaw, Research Assistant and Daw Cho Cho Win, Research Assistant, Forest Research Institute August, 1997 i Acknowledgements Technical discussion sections were held with U Soe Myint, Director of the regreening of the nine districts in the central dryzone of Myanmar, his extensive knowledge of the dryzone together with his general support proved most useful. At the field level, Assistant Directors (District Forest Officers) and Staff Officers (Township Forest Officers), made available all essential support and facilities. Their contributions and support are most appreciated and made it possible to complete this paper. Thanks are due to the laboratory technicians, Forest Soil Laboratory, Forest Research Institute, for their service to finish this paper in time. ii tyllyddkkiff;a'o ( 9 ) c&ddkkiffpddkkuffciff;ajrrsm;\*kkPffowååddESSiffhh toHHkk;csrSSKuddkk pll;prff;avhhvmjciff; ('kkwdd,yddkkiff; ) OD;pef;vGif? B.Sc.(For.) (Ygn.), M.S. ( CESF, SUNY ) 'kwd,nTefMum;a&;rSL; OD;xifausmf? B.Sc. ( I.C. ) ( Ygn. ) okawoevufaxmuf ESifh a':csdKcsdK0if;? B.Sc.(Chem.) ( Mdy.) okawoevufaxmuf opfawmokawoe? a&qif;/ pmwrff;tusOff;csKyff tylydkif; a'o(9)c&dkif pdkufcif;ajrrsm;\ "gwkESifh&ly *kPof wååddrsm;tm; pl;l prff;avhhvmrSSK ( 'kkwdd,yddkkiff; ) jzpffygonff/ pddkkuffciff;ajrrsm;\ *kPfowådESifh qufEG,fvsuf&Sddaom taMumif;jcif;&m rsm;tm; uGif;qif; avhvmrSKtay: tajccHí wifjyxm;ygonf/ yxrydkif;ESifh 'kwd,ydkif; aygif;pnf;í tylydkif; a'o pdkufcif;rsm; wnfaxmif&mwGif tudk;tum;jyK toHk;csEdkifrnf jzpfygonf/ a&Tbdkc&dkifudkyg wdk;csJ. -

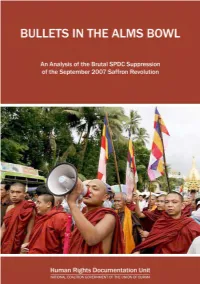

Bullets in the Alms Bowl

BULLETS IN THE ALMS BOWL An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution March 2008 This report is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives for their part in the September 2007 pro-democracy protests in the struggle for justice and democracy in Burma. May that memory not fade May your death not be in vain May our voices never be silenced Bullets in the Alms Bowl An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution Written, edited and published by the Human Rights Documentation Unit March 2008 © Copyright March 2008 by the Human Rights Documentation Unit The Human Rights Documentation Unit (HRDU) is indebted to all those who had the courage to not only participate in the September protests, but also to share their stories with us and in doing so made this report possible. The HRDU would like to thank those individuals and organizations who provided us with information and helped to confirm many of the reports that we received. Though we cannot mention many of you by name, we are grateful for your support. The HRDU would also like to thank the Irish Government who funded the publication of this report through its Department of Foreign Affairs. Front Cover: A procession of Buddhist monks marching through downtown Rangoon on 27 September 2007. Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstrations, the SPDC cracked down on protestors with disproportionate lethal force [© EPA]. Rear Cover (clockwise from top): An assembly of Buddhist monks stage a peaceful protest before a police barricade near Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on 26 September 2007 [© Reuters]; Security personnel stepped up security at key locations around Rangoon on 28 September 2007 in preparation for further protests [© Reuters]; A Buddhist monk holding a placard which carried the message on the minds of all protestors, Sangha and civilian alike. -

Republic of the Union of Myanmar Preparatory Survey on Distribution

Electricity Supply Enterprise Ministry of Electric Power Republic of the Union of Myanmar Republic of the Union of Myanmar Preparatory Survey on Distribution System Improvement Project in Main Cities Final Report July 2015 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Chubu Electric Power Co., Inc. 1R Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. JR 15-033 Table of contents Chapter 1 Background ........................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Survey schedule .......................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.3 JICA survey team and counterpart .............................................................................................. 1-5 Chapter 2 Present Status ........................................................................................................ 2-1 2.1 Present status of the power distribution sector ........................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Movement of Corporatization and franchising ........................................................................... 2-6 2.3 Electricity Tariff .......................................................................................................................... 2-7 2.3.1 Number of Consumers ....................................................................................................... -

Data Collection Survey on the Project for Development of Water Saving Agricultural Technology in the Central Dry Zone in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar

Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation The Republic of the Union of Myanmar DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON THE PROJECT FOR DEVELOPMENT OF WATER SAVING AGRICULTURAL TECHNOLOGY IN THE CENTRAL DRY ZONE IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR FINAL REPORT AUGUST 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) SANYU CONSULTANTS INC. India China 51 Townships in the Central Dry Zone and Main Facilities of the Project Project Area Myanmar Yangon Thai Sagaing Region Myingyan DAR Center Mandalay Region Nyaung Oo DAR Center Magway DAR Center Magway Region Nay Pyi Taw Legend Border Border of Region Border of Township Project Area Division/ State Capital District Capital River Road Railway Photos of the Central Dry Zone Rainfed upland(before rainy season) Seeding at the beginning of rainy season Predominant sandy soil (before rainy season) Indian-made 4 wheel tractor Plowing by Power tiller Intercropping with groundnut and pigeon pea Intercropping with groundnut and maize Tube-well observed in Central Dry Zone Hydroponic irrigation (Magway Campus, Practice of the hydroponic irrigation in a Yezin Agricultural University ) village (Yenangyon) Practice of micro irrigation in a village Practice of micro irrigation in a (Yenangyon) village(Yenangyon) Dragon fruits (Mandalay) Bean Exchange market (Mandalay) Oil-extracting factory (Myingyan) Bean –processing factory (Myingyan) CONTENTS Location Map of the Study Area Photos of the Central Dry Zone CHAPTER 1 BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES ············································ 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................... -

Needs Assessment of Income Generation Training for Youths Among Leprosy Families in a Leprosy Village in Myanmar

Jpn. J. Leprosy 76, 197-206(2007) Needs assessment of income generation training for youths among leprosy families in a leprosy village in Myanmar Yutaka ISHIDA*1, San SHWE2, Le Le WIN2), Kyaw MYINT3 I )Bureau of InternationalCooperation, InternationalMedical Center of Japan, Japan 2)Department of Medical Research (Lower Myanmar),Ministry of Health, Union of Myanmar 3)Department of Health, Ministry of Health, Union of Myanmar [Received: 20 Nov. 2006/Accepted: 5 April. 2007] Key words : income generation training, leprosy, Myanmar, needs assessment, stigma After Myanmar eliminated leprosy in 2003, the prevention of disability (POD), as well as prevention of worsening disabilities (POWD) and rehabilitation became a new agenda, which is one of three national strategies of leprosy control beyond 2005. Since the training needs for income generation for youths liv- ing in leprosy villages were not well known, a small-scale survey was conducted in May 2005. This study found that the youths in Mayanchaung village, Yangon Division, were eager to receive training on income generation. After training they wanted to practice and improve their skills with the resources available, be- cause they perceived that a short training course would not enable them to get a proper job. Although they were fully aware of income generation skills, they found it difficult to adequately consider issues such as resources for practicing skills after training, social marketing, and seeking job opportunities. They also felt that mediators could be helpful between villagers and external customers/retailers. On the other hand, the elders, most of whom had disabilities, wanted the youths to stay in the village to take care of them. -

46390-003: Power Distribution Improvement Project

Environmental Safeguard Monitoring Report #4th Semi-Annual Report June 2018 Project No. 46390-003 MYA: Power Distribution Improvement Project Prepared by Electricity Supply Enterprise (ESE) through the Ministry of Electricity and Energy (MOEE) of the Union of the Myanmar Republic and the Asian Development Bank. This Environmental Safeguard monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or área. 1 | P a g e The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Electricity and Energy Electricity Supply Enterprise (ESE) Power Distribution Improvement Project Loan No: 3084-MYA (SF) Semi-annually Safeguard Monitoring Report January - June 2018 1 | P a g e Contents Scope ......................................................................................................... 3 Introduction and Project Characteristics...................................... 3 1.1 Background............................................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Objectives of the Project.................................................................................................................. -

1 Asia Farmer-To-Farmer

Asia Farmer-to-Farmer The Asia Farmer-to-Farmer (F2F) Program goal is to generate rapid, sustainable, and broad-based food security and economic growth in the agricultural sector. A secondary goal is to increase the American public’s understanding of international development issues and programs and international understanding of the U.S. and U.S. development programs. Winrock International was awarded the five-year Asia F2F Program on September 2013. Specifically in Burma, F2F activities are aligned with USAID/Burma’s Food Security and Agricultural Transition Framework to improve productivity and profitability of agriculture; increase private sector engagement in the agriculture sector; and introduce innovative technologies for rural economic development. In the first three years of the program (October 2013 – September 2016), Burma F2F completed 56 volunteer trips to support rural development and increased incomes for smallholder farmers. Volunteers trained and assisted 4,530 farmers and other agriculture sector stakeholders (34% women) to improve productivity, increase food safety, and strengthen farmer-serving organizations in Mandalay, Sagaing, Bago, Ayeyarwaddy, Magway, and Yangon regions, as well as in Chin and Southern Shan states. Introduction of simple, low-cost technologies in the livestock, aquaculture, and horticulture sectors has helped smallholder farmers reduce costs, improve productivity, and increase sales. Burma F2F Assignments in Poultry & Livestock Poultry Improved Poultry Feed Formulation Leonard Obaldo, 9/24/2014-9/27/2014, Mandalay and Madaya Host organization: Mandalay Livestock Development Company Limited Dr. Obaldo provided training on poultry digestion, nutritional requirements, and nutritional value of locally available feed ingredients. He also led hands-on demonstrations on how to calculate poultry feed formulations manually and using an Excel sheet. -

Shop Name State / Division Township Address

Shop Name State / Division Township Address MPT Pathein Ayarwaddy AYW - Pathein Division Manager office,MPT, Maharbandula street, Ayarwaddy Division, Pathein Township . MPT Hinthada Ayarwaddy AYW - Hinthada Hinthada Auto Exchange, Bogyoke Street , Hinthada Township . MPT Zalun Ayarwaddy AYW - Zalun Zalun Auto Exchange, Ahdar street,Zalun Township . MPT Bokalay Ayarwaddy AYW - Bokalay Bokalay Auto exchange, Bokalay Street, No(4) quarter, Bokalay Township . MPT Pyarpon Ayarwaddy AYW - Pyarpon Pyarpon Auto Exchange, No(5) Street, (12) quarter , Pyarpon Township . MPT Myaungmya Ayarwaddy AYW - Myaungmya Auto Exchange ,Tout Yaung Nay Street ,Myaungmya Township . MPT Nyaung Tone Ayarwaddy AYW - Nyaung Tone Cable Office ,No.6 Quarter ,Nyaung Tone Township . MPT Myan Aung Ayarwaddy AYW - MyanAung Auto Exchange , Sartitetaegone Street ,Myan Aung Township . MPT Maubin Ayarwaddy AYW - Maubin Mobile + Micro Building ,No.1 Quarter ,Maubin Township . MPT Kyonepyaw Ayarwaddy AYW - Kyonpyaw Kyone Pyaw Auto Exchange, Bogyoke St, Aung San ward, Kyonepyaw Tsp MPT Bago Bago BGO - Bago Yangon-Mandalay Street, near NaryiSin , Division Manager Office , Bago Township . MPT Pyay Bago BGO - Pyay Yangon-Pyay street, Sin Su Carrier office compound , Pyay Township . MPT Min Hla Bago BGO - Min Hla No(7) Quarter, Boyontan Street, Minhla auto exchange , Minhla Township . MPT Latpandan Bago BGO - Latpandan No(2) Street, Min Quarter, Latpandan Auto Exchange , Latpandan Township . MPT Paukhong Bago BGO - Paukhong Pyay-Taungoo Street, number (5) quarter, Paukhoung Township . MPT Taungoo Bago BGO - Taungoo Main road, Auto Exchange Compound, Taungoo Township , MPT Tharrawaddy Bago BGO - Tharrawaddy Micro Compound ,Tharrawaddy Township . MPT Hakha Chin CHN - Hakha MPT State Manager Office, Zay(1) Quarter, Matupi Street,Hakha Township . Myitkyina MPT mobile,In front of Thit Taw Office, Corner of Sama street and Zaw Gyone Street, Ayar MPT Myitkyina Kachin KCN - Myitkyina Quarter,Myitkyina Township . -

46390-003: Power Distribution Improvement Project

Environmental and Social Monitoring Report #5th Semi-Annual Report 31 December 2018 Project No. 46390-003, Loan No. 3084 MYA: Power Distribution Improvement Project Prepared by Electricity Supply Enterprise (ESE) through the Ministry of Electricity and Energy (MOEE) of the Union of the Myanmar Republic and the Asian Development Bank. This Environmental and Social Monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. 0 | P a g e Ministry of Electricity and Energy Electricity Supply Enterprise (ESE) Power Distribution Improvement Project Loan No: 3084-MYA (SF) Semi-annually Social Monitoring Report July - December 2018 1 | P a g e Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................... 2 Scope ............................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction and Project Characteristics ................................................................................. 3 1.1 Background ...........................................................................................................