Supply Chain Management of Sesame Under Informal Contract Scheme in Aunglan Township, Magway Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar Receives 30,000 Remdesivir Drugs Used in COVID-19 Treatment from NSIC

DON’T BE TOO FEARFUL BUT TAKE CARE OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL MoC facilitates import of COVID-19 MoHS Union Minister discusses COVID-19-related devices to be delivered without delay on matters with Yangon Region Administration public holidays Council members, regions/states health officials PAGE-3 PAGE-4 Vol. VIII, No. 93, 13th Waxing of Waso 1383 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Wednesday, 21 July 2021 Five-Point Road Map of the State Administration Council 1. The Union Election Commission will be reconstituted and its mandated tasks, including the scrutiny of voter lists, shall be implemented in accordance with the law. 2. Effective measures will be taken with added momentum to prevent and manage the COVID-19 pandemic. 3. Actions will be taken to ensure the speedy recovery of businesses from the impact of COVID-19. 4. Emphasis will be placed on achieving enduring peace for the entire nation in line with the agreements set out in the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement. 5. Upon accomplishing the provisions of the state of emergency, free and fair multiparty democratic elections will be held in line with the 2008 Constitution, and further work will be undertaken to hand over State duties to the winning party in accordance with democratic standards. Myanmar receives 30,000 Remdesivir drugs used in COVID-19 treatment from NSIC A TATMADAW aircraft landed at Nay Pyi Taw Airport, carry- ing 30,000 Remdesivir drugs donated by the National Stra- tegic Investment Corporation Co. Ltd (NSIC) to the State Administration Council from Hyderabad, India, yesterday evening. -

Myanmar-Government-Projects.Pdf

Planned Total Implementing Date Date Last Project Project Planned Funding Financing Tender Developer Sector Sr. Project ID Description Expected Benefits End Project Government Ministry Townships Sectors MSDP Alignment Project URL Created Modified Title Status Start Date Sources Information Date Name Categories Date Cost Agency The project will involve redevelopment of a 25.7-hectare site The project will provide a safe, efficient and around the Yangon Central Railway Station into a new central comfortable transport hub while preserving the transport hub surrounded by housing and commercial heritage value of the Yangon Central Railway Station amenities. The transport hub will blend heritage and modern and other nearby landmarks. It will be Myanmar’s first development by preserving the historic old railway station main ever transit-oriented development (TOD) – bringing building, dating back in 1954, and linking it to a new station residential, business and leisure facilities within a constructed above the rail tracks. The mixed-use development walking distance of a major transport interchange. will consist of six different zones to include a high-end Although YCR railway line have been upgraded, the commercial district, office towers, condominiums, business image and performance of existing railway stations are hotels and serviced apartments, as well as a green park and a still poor and low passenger services. For that railway museum. reason, YCR stations are needed to be designed as Yangon Circular Railway Line was established in 1954 and it has attractive, comfortable and harmonized with city been supporting forYangon City public transportation since last development. On the other hand, we also aligned the 60 years ago. -

IPNI Library As References

International Plant Nutrition Institute Regional Office • Southeast Asia Date: September 15, 2017 Page: 1 of 109 New Entries to IPNI Library as References [1] J. Hawksworth, H. Audino, R. Clarry, Secondary J. Hawksworth, H. Audino, R. Clarry. 2017. The Long View: How will the global economic order change by 2050? Page 1 - 72. Reference ID: 23486 Note: H 8.1.1.5 #23486e Abstract: After a year of major political shocks with the Brexit vote and the election of President Trump, it might seem brave to opine on economic prospects for 2017, let alone 2050. However, I still think it is important to take a longer term view of global economic prospects that looks beyond the short-term ups and downs of the economic and political cycle, which are indeed very difficult to forecast. Instead our approach in this report, based on a rigorous modelling approach, focuses on the fundamental drivers of growth: demographics and productivity, which in turn is driven by technological progress and diffused through international trade and investment. Such forces saw America progress through the 19th and early 20th centuries to become the largest economy in the world despite a civil war, various other conflicts with foreign powers, three presidential assassinations, and numerous economic and financial crises. These forces also helped global economic growth to bounce back strongly from two world wars and a Great Depression to reach record levels in the post-war decades. Looking ahead, we think they will see emerging economies come to dominate the 21st century. By 2050 we project China will be the largest economy in the world by a significant margin, while India could have edged past the US into second place and Indonesia have risen to fourth place. -

The Myanmar-Thailand Corridor 6 the Myanmar-Malaysia Corridor 16 the Myanmar-Korea Corridor 22 Migration Corridors Without Labor Attachés 25

Online Appendixes Public Disclosure Authorized Labor Mobility As a Jobs Strategy for Myanmar STRENGTHENING ACTIVE LABOR MARKET POLICIES TO ENHANCE THE BENEFITS OF MOBILITY Public Disclosure Authorized Mauro Testaverde Harry Moroz Public Disclosure Authorized Puja Dutta Public Disclosure Authorized Contents Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar 1 Appendix 2 Forms used to collect information at Labor Exchange Offices 3 Appendix 3 Registering jobseekers and vacancies at Labor Exchange Offices 5 Appendix 4 The migration process in Myanmar 6 The Myanmar-Thailand corridor 6 The Myanmar-Malaysia corridor 16 The Myanmar-Korea corridor 22 Migration corridors without labor attachés 25 Appendix 5 Obtaining an Overseas Worker Identification Card (OWIC) 29 Appendix 6 Obtaining a passport 30 Cover Photo: Somrerk Witthayanant/ Shutterstock Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar State/Region Name State/Region Name Yangon No (1) LEO Tanintharyi Dawei Township Office Yangon No (2/3) LEO Tanintharyi Myeik Township Office Yangon No (3) LEO Tanintharyi Kawthoung Township Office Yangon No (4) LEO Magway Magwe Township Office Yangon No (5) LEO Magway Minbu District Office Yangon No (6/11/12) LEO Magway Pakokku District Office Yangon No (7) LEO Magway Chauk Township Office Yangon No (8/9) LEO Magway Yenangyaung Township Office Yangon No (10) LEO Magway Aunglan Township Office Yangon Mingalardon Township Office Sagaing Sagaing District Office Yangon Shwe Pyi Thar Township Sagaing Monywa District Office Yangon Hlaing Thar Yar Township Sagaing Shwe -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

The Properties and Utilization of Soilin the Greening Project for the Ninecritical Districts of the Arid Zone of Central Myanmar ( Part II )

Leaflet No. 3/1997 Government of theUnion of Myanmar Ministry of Forestry Forest Department The Properties and Utilization of Soilin the Greening Project for the NineCritical Districts of the Arid Zone of Central Myanmar ( Part II ) U Sann Lwin (2), Deputy Director, U Htin Kyaw, Research Assistant and Daw Cho Cho Win, Research Assistant, Forest Research Institute August, 1997 i Acknowledgements Technical discussion sections were held with U Soe Myint, Director of the regreening of the nine districts in the central dryzone of Myanmar, his extensive knowledge of the dryzone together with his general support proved most useful. At the field level, Assistant Directors (District Forest Officers) and Staff Officers (Township Forest Officers), made available all essential support and facilities. Their contributions and support are most appreciated and made it possible to complete this paper. Thanks are due to the laboratory technicians, Forest Soil Laboratory, Forest Research Institute, for their service to finish this paper in time. ii tyllyddkkiff;a'o ( 9 ) c&ddkkiffpddkkuffciff;ajrrsm;\*kkPffowååddESSiffhh toHHkk;csrSSKuddkk pll;prff;avhhvmjciff; ('kkwdd,yddkkiff; ) OD;pef;vGif? B.Sc.(For.) (Ygn.), M.S. ( CESF, SUNY ) 'kwd,nTefMum;a&;rSL; OD;xifausmf? B.Sc. ( I.C. ) ( Ygn. ) okawoevufaxmuf ESifh a':csdKcsdK0if;? B.Sc.(Chem.) ( Mdy.) okawoevufaxmuf opfawmokawoe? a&qif;/ pmwrff;tusOff;csKyff tylydkif; a'o(9)c&dkif pdkufcif;ajrrsm;\ "gwkESifh&ly *kPof wååddrsm;tm; pl;l prff;avhhvmrSSK ( 'kkwdd,yddkkiff; ) jzpffygonff/ pddkkuffciff;ajrrsm;\ *kPfowådESifh qufEG,fvsuf&Sddaom taMumif;jcif;&m rsm;tm; uGif;qif; avhvmrSKtay: tajccHí wifjyxm;ygonf/ yxrydkif;ESifh 'kwd,ydkif; aygif;pnf;í tylydkif; a'o pdkufcif;rsm; wnfaxmif&mwGif tudk;tum;jyK toHk;csEdkifrnf jzpfygonf/ a&Tbdkc&dkifudkyg wdk;csJ. -

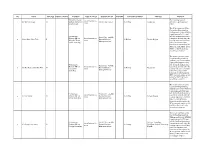

Warrant Lists English

No Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Minister of Social For encouraging civil Issued warrant to 1 Dr. Win Myat Aye M Welfare, Relief and Penal Code S:505-a In Hiding Naypyitaw servants to participate in arrest Resettlement CDM The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 2 (Daw) Phyu Phyu Thin F Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region Mingalar Taung arrest coup in response to military Management law Nyunt Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 3 (U) Yee Mon (aka) U Tin Thit M Natural Disaster In Hiding Naypyitaw Potevathiri arrest coup in response to military Management law Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and self-declared parliamentary Pyihtaungsu Penal Code - 505(B), Issued warrant to committee formed after the 4 (U) Tun Myint M Hluttaw MP for Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region arrest coup in response to military Bahan Township Management law rule. -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2006 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 6, 2007

Burma Page 1 of 22 Burma Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2006 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 6, 2007 Since 1962 Burma, with an estimated population of 54 million, has been ruled by a succession of highly authoritarian military regimes dominated by the majority Burman ethnic group. The State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), led by Senior General Than Shwe, was the country's de facto government, with subordinate peace and development councils ruling by decree at the division, state, city, township, ward, and village levels. Military officers wielded the ultimate authority at each level of government. In 1990 prodemocracy parties won more than 80 percent of the seats in a general parliamentary election, but the regime continued to ignore the results. The military government totally controlled the country's armed forces, excluding a few active insurgent groups. The government's human rights record worsened during the year. The regime continued to abridge the right of citizens to change their government. The government detained five leaders of the 88 Generation Students prodemocracy activists. The government refused to allow the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to visit prisoners privately. The army increased attacks on ethnic minority villagers in Bago Division and Karen State designed to drive them from their traditional land. In addition, the government continued to commit other serious abuses, including extrajudicial killings, custodial deaths, disappearances, rape, and torture. The government abused prisoners and detainees, held persons in harsh and life threatening conditions, routinely used incommunicado detention, and imprisoned citizens arbitrarily for political motives. -

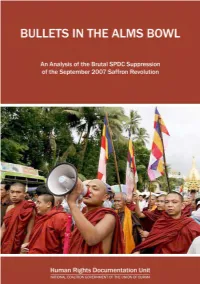

Bullets in the Alms Bowl

BULLETS IN THE ALMS BOWL An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution March 2008 This report is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives for their part in the September 2007 pro-democracy protests in the struggle for justice and democracy in Burma. May that memory not fade May your death not be in vain May our voices never be silenced Bullets in the Alms Bowl An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution Written, edited and published by the Human Rights Documentation Unit March 2008 © Copyright March 2008 by the Human Rights Documentation Unit The Human Rights Documentation Unit (HRDU) is indebted to all those who had the courage to not only participate in the September protests, but also to share their stories with us and in doing so made this report possible. The HRDU would like to thank those individuals and organizations who provided us with information and helped to confirm many of the reports that we received. Though we cannot mention many of you by name, we are grateful for your support. The HRDU would also like to thank the Irish Government who funded the publication of this report through its Department of Foreign Affairs. Front Cover: A procession of Buddhist monks marching through downtown Rangoon on 27 September 2007. Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstrations, the SPDC cracked down on protestors with disproportionate lethal force [© EPA]. Rear Cover (clockwise from top): An assembly of Buddhist monks stage a peaceful protest before a police barricade near Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on 26 September 2007 [© Reuters]; Security personnel stepped up security at key locations around Rangoon on 28 September 2007 in preparation for further protests [© Reuters]; A Buddhist monk holding a placard which carried the message on the minds of all protestors, Sangha and civilian alike. -

Village Tracts of Thayet Township Magway Region

Myanmar Information Management Unit Village Tracts of Thayet Township Magway Region 94°54’E 95°0’E 95°6’E 95°12’E Nyaung Ywar Nge Ta t Moe Nat Kone Gon Ma Ni Shwe Pan Kaing Htee Yoe Baw Kyar Kan Inn Lel 19°30’N 19°30’N Tha Yet Myint Pauk Taw Ah Lat Lel Sin Thay Pun Gyi Myauk Kyut Yae Bwet Kya U Oke Shit Kone San Lel Kun Ohn Taw Myin Thar Mya Sa Kaing Ohn Mun Taw Ban Pyin Nyaung Zit Nga Hlaing Chon 19°24’N 19°24’N Pay Ka Tin Hman Din Gyi THAYET Let Pan Seik Pi Tauk Pin Yae Myet Yae Hpyu Kyauk Oe San Aint Koe Pin Inn Ma Nge Ta La Par Urban Thayet Yae Paw Ban Kone Pyin Htaung Kyun Min Te 19°18’N 19°18’N Htone Taung Twin Lel Pyin Aing Peik Tha Lein Pauk U Kar Sin Kaw To n Pon Nar Sagaing Pya Yae Gyoe Gyar Chin 19°12’N 19°12’N Shan Mandalay Ywar Ma Par Put Magway Bay of Bengal Rakhine Bago Kilometers 0241 Ayeyarwady 94°54’E 95°0’E 95°6’E 95°12’E Map ID: MIMU575v01 Legend Data Sources : GLIDE Number: TC-2010-000211-MMR Cyclone BASE MAP - MIMU State Capital Road Village Tract Boundaries Creation Date: 3 December 2010. A3 Boundaries - WFP/MIMU/UNICEF Township Boundary Cyclone Path Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 Main Town Place names - Ministry of Home Affair District Boundary Other Town (GAD) translated by MIMU State Boundary Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] Website : http://www.themimu.info Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

The Transformation of Weaving in Myanmar from the Tradition to the Modernity and Its Impact

The Transformation of Weaving in Myanmar from the Tradition to the Modernity and Its Impact Yan Naing Lin1 Abstract Myanmar traditional handicrafts such as silversmith, goldsmith and weaving suffered eclipse under the penetration of the western culture, especially, the weaving experienced the great challenge by the domination of the western textiles under the Luissez Faire policy practiced by the British. Together with the exhortation of Myanmar nationalist leaders of YMBA in order to uplift the traditional weaving, Saunders Weaving School came to be emerged under the endeavor of Mr. Saunders. He intended to produce more clothes by means of modernized looms in order to uplift the social life of the weavers and therefore he attempted to transform the conventional weaving craft and to spread it to the whole country. As a result of this effort, many weaving schools came to be developed alongside many private weaving factories throughout the country. Also the Saunders Weaving Institute helped to the development of Lun-yar-kyaw Acheik by combination of traditional methods and modernized instruments. This paper is intended to explore how the weaving in Myanmar continued to develop, survive and how the traditional method was transformed into the modernity. Introduction The weaving craft which had been existed since the Pyu period in Myanmar came to be developed successively throughout the ages and then it was prosperous together with the combination of the weaving craft of Manipur. Together with the development of Lun-yar kyaw Acheik , Amarapura Township became a centre of weaving industry from the Amarapura period to the Yatanabon Period. During the British colonial period, Myanmar weaving industry faced the great challenge by the foreign textiles which were imported under the policy of free trade. -

Republic of the Union of Myanmar Preparatory Survey on Distribution

Electricity Supply Enterprise Ministry of Electric Power Republic of the Union of Myanmar Republic of the Union of Myanmar Preparatory Survey on Distribution System Improvement Project in Main Cities Final Report July 2015 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Chubu Electric Power Co., Inc. 1R Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. JR 15-033 Table of contents Chapter 1 Background ........................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Survey schedule .......................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.3 JICA survey team and counterpart .............................................................................................. 1-5 Chapter 2 Present Status ........................................................................................................ 2-1 2.1 Present status of the power distribution sector ........................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Movement of Corporatization and franchising ........................................................................... 2-6 2.3 Electricity Tariff .......................................................................................................................... 2-7 2.3.1 Number of Consumers .......................................................................................................