Sequential Disaster Forensics: an Application to Floods in the City of Grima

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

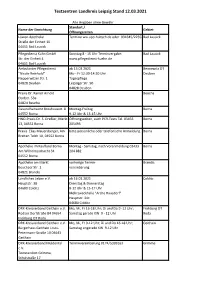

Testzentren Landkreis Leipzig Stand 12.03.2021

Testzentren Landkreis Leipzig Stand 12.03.2021 Alle Angaben ohne Gewähr Standort / Name der Einrichtung Gebiet Öffnungszeiten Löwen Apotheke Termine ww.apo-hultsch.de oder 034345/22352Bad Lausick Straße der Einheit 10 04651 Bad Lausick Pflegedienst Kühn GmbH Sonntag 8 - 15 Uhr Terminvergabe: Bad Lausick Str. der Einheit 4 www.pflegedienst-kuehn.de 04651 Bad Lausick Ambulanter Pflegedienst ab 15.03.2021 Bennewitz OT "Nicole Reinhold" Mo - Fr 12:30-14:30 Uhr Deuben Nepperwitzer Str. 1 Tagespflege 04828 Deuben Leipziger Str. 90 04828 Deuben Praxis Dr. Rainer Arnold Beucha Dorfstr. 53a 04824 Beucha Gesundheitsamt Brauhausstr. 8 Montag-Freitag Borna 04552 Borna 9-12 Uhr & 13-15 Uhr HNO-Praxis Dr. S. Dreßler, Markt Öffnungszeiten, auch PCR-Tests Tel. 03433 Borna 13, 04552 Borna 205495 Praxis Elias Mauersberger, Am bitte persönliche oder telefonische Anmeldung. Borna Breiten Teich 10, 04552 Borna Apotheke im Kaufland Borna Montag - Samstag, nach Voranmeldung 03433 Borna Am Wilhelmsschacht 34 204 882 04552 Borna Apotheke am Markt vorherige Termin- Brandis Beuchaer Str. 1 vereinbarung 04821 Brandis Ländliches Leben e.V. ab 16.03.2021 Colditz Hauptstr. 38 Dienstag & Donnerstag 04680 Colditz 8-12 Uhr & 15-17 Uhr Mehrzweckhalle "Arche Hausdorf" Hauptstr. 34c 04680 Colditz DRK-Kreisverband Geithain e.V. Mo, Mi, Fr 16-18 Uhr; Di und Do 9 -12 Uhr; Frohburg OT Rodaer Dorfstraße 84 04654 Samstag gerade KW 9 - 12 Uhr Roda Frohburg OT Roda DRK-Kreisverband Geithain e.V. Mo, Mi, Fr 9-12 Uhr; Di und Do 16-18 Uhr; Geithain Bürgerhaus Geithain Louis- Samstag ungerade KW 9-12 Uhr Petermann-Straße 10 04643 Geithain DRK-Kreisverband Muldental Terminvereinbarung 0174/5399163 Grimma e.V. -

Testzentren Landkreis Leipzig Stand 07.05.2021

Testzentren Landkreis Leipzig Stand 07.05.2021 Zu den genannten Einrichtungen bieten auch Ärzte die Tests an Name der Einrichtung Standort / Gebiet Versorgungsform Öffnungszeiten TmH Transport mit Telefonische Terminvereinbarung mobil Sonstiges Herz,Hauptstr. 66 unter 034345 55751 Kerstin 04668 Otterwisch Engelmann DRK Kreisverband Terminvergabe: mobil Sonstiges Muldental e.V. www.drkmuldental.de/schnelltest Standorte Walther-Rathenau-Str. oder 0174 5499100 oder 0174 Nerchau, 1, 04808 Wurzen 5399163 Dürrweitzschen, Mutzschen, Großbardau, Großbothen lola-Aquarium Netto-Markt 9-17 Uhr mobil Sonstiges Ostenstr. 9 Montag: Carsdorfer Str. 8 Pegau Netto-Märkte in 08527 Plauen Dienstag: Schusterstr. 6 Groitzsch Pegau, Mittwoch / Freitag: Groitzsch und Pawlowstr. 2a Borna Borna Donnerstag: Deutzener Str. 7 Borna Löwen Apotheke Termine ww.apo-hultsch.de oder Bad Lausick Apotheke Straße der Einheit 10 034345/22352 04651 Bad Lausick Pflegedienst Kühn Mo - Fr von 13 - 14:30 Uhr, So von Bad Lausick amb. PD GmbH, Str. der Einheit 8 - 15 Uhr Terminvergabe: 4, 04651 Bad Lausick www.pflegedienst-kuehn.de DRK-Kreisverband Kur- und Freizeitbad Riff Bad Lausick Geithain e.V. Am Riff 3, 04651 Bad Lausick Kreisgeschäftsstelle Dresdener Str. 33 b Mo / Mi / Do 9 – 11 Uhr 04643 Geithain Di / Fr 16 – 18 Uhr Häusliche Kranken- Mittwoch 9 - 15 Uhr Bad Lausick Sonstiges und Altenpflege Dorothea Petzold GmbH, Fabianstr. 6 04651 Bad Lausick DRK-Kreisverband Kur- und Freizeitbad Riff Bad Lausick Hilforga- Geithain e.V. Am Riff 3, 04651 Bad Lausick nisation Kreisgeschäftsstelle Mo / Mi / Do 9 – 11 Uhr Dresdener Str. 33 b Di / Fr 16 – 18 Uhr 04643 Geithain DRK WPS im DRK Pflegedienst Bennewitz Bennewitz Sonstiges Muldental GmbH, Leipziger Str. -

693-U Umleitungsfahrplan: Grimma

PERSONENVERKEHRSGESELLSCHAFT MULDENTAL Firmensitz Deuben Betriebsteil Deuben Betriebsteil Grimma Leipziger Str. 79 Leipziger Str. 79 Bahnhofstr. 5, Haus 25 04828 Deuben 04828 Deuben 04668 Grimma www.pvm-mtl.de Telefon: (0 34 25) 89 89 89 693-U Umleitungsfahrplan: Grimma - Trebsen - Pausitz - Bennewitz - Wurzen P gültig ab 22.09.2014 Verkehrstage Montag - Freitag (nicht Feiertag) Fahrtnummer 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 Tarifzone Verkehrshinweise 3 / / / / aus Ri Leipzig Zug ................................................................................ 5:42 6:42 7:41 8:41..... 10:41 12:41 13:41 ... 14:41 15:41 16:42 17:41 18:41 519/144 Grimma, Bf Bst 5 ..................................ab ................................................... 5:56 6:56 7:56 8:56..... 10:56 12:56 13:56 14:18 14:56 15:56 16:56 17:56 18:56 519/144 Grimma, Nicolaiplatz Bst 5 ........................................................................... 6:01 7:01 8:01 9:01..... 11:01 13:01 14:01 14:23 15:01 16:01 17:01 18:01 19:01 519/144 Hohnstädt, Wurzener Str .............................................................................. 6:06 7:06 8:06 9:06..... 11:06 13:06 14:06 14:28 15:06 16:06 17:06 18:06 19:06 144 Trebsen, Grimmaische Str ............................................................................. 6:21 7:21 8:21 9:21..... 11:21 13:21 14:21 14:43 15:21 16:21 17:21 18:21 19:21 144 Trebsen, Am Markt .................................................................................... 6:23 7:23 8:23 9:23..... 11:23 13:23 14:23 14:45 15:23 16:23 17:23 18:23 19:23 144 Abzw nach Walzig ..................................................................................... 6:25 7:25 8:25 9:25.... -

The State Reservoir Administration of Saxony Property from Floods

Masthead Publisher: Landestalsperrenverwaltung des Freistaates Sachsen Bahnhofstraße 14, 01796 Pirna, Germany Internet: www.talsperren-sachsen.de Tel.: +49 (0) 3501 796 – 0, Fax: +49 (0) 3501 796-116 E-mail: [email protected] Editors: Press and Public Relations Copy Deadline: February 2007 Photographs: Landestalsperrenverwaltung des Freistaates Sachsen, Kirsten J. Lassig, www.photocase.com Circulation: 1,000 copies Design: Heimrich & Hannot GmbH Printing: Druckfabrik Dresden GmbH Paper: 100 % chlorine free bleached THE STATE RESERVOIR (No access for electronically signed as well as for encrypted electronic documents) ADMINIstrATION OF SAXONY Note This informational brochure is published by the Saxon State Government in the scope of its public relations work. It may not be used by parties or campaign Function – Organization – Projects aids for the purpose of election advertising. This is valid for all elections. CONTENts 4 10 12 14 18 24 FOREWORD ORGANIZATION OF THE THE NERVE CENTER ON-SITE EXPERTISE: Zwickauer Mulde/ FLOOD PROTECTION AND STATE RESERVOIR OF THE STATE RESERVOIR THE REGIONAL WORKS Obere Weiße Elster DRINKING WATER SUPPLy – 5 ADMINISTRATION OF SAXONY ADMINISTRATION OF SAXONY: TWO EXAMPLES STEWARDSHIP HEADQUARTERS IN PIRNA 14 20 OF SAXony’S WATERS Oberes Elbtal Spree/Neiße 24 Function of the State Reservoir Comprehensive flood protection Administration of Saxony 16 22 for the city of Torgau Freiberger Mulde/ Elbaue/Mulde/ Zschopau Untere Weiße Elster 26 Complex overhaul of the Klingenberg dam 2 CONTENTS 3 FOREWORD The first water reservoirs in Saxony were built as Saxony was founded in 1992 as the first public early as 500 years ago. The mining industry was enterprise in Saxony. -

Land Use Effects and Climate Impacts on Evapotranspiration and Catchment Water Balance

Institut für Hydrologie und Meteorologie, Professur für Meteorologie climate impact Q ∆ ∆ E ● p basin impact ∆Qobs − ∆Qclim P ● ● ● P ● ● ● ●● ●● ● ●● ● −0.16 ●●● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●●●●●●● ●●●●● ● ●●● ●● ● ●● ●● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●●●● U −0.08 ● ● ●● ●● ●●● ● ● ●● ● ●● ● ● ●● ●● ● ● ●● ∆ ● ● ● ● ● ● ●●● ● ● ●●● ●● ● ● ●●●●●● ● ●●●● ●● ●●●● ●●● ● ●●●● ● ● 0 ● ●● ● ●●●●● ● ● ● ● ●●● ● ● ●●●●●● ● ●● ● ● ● ●● ● ● ●● ● ●● ● ● ●● ●● ● ●● ●● ●●● ●●● ● ● ● ●● ●● ● ● ●● 0.08 ● ● ●●● ●●● ●●● ● ●● ● ●●●● ● ● ● ● ●●● ●●●● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●●●●●●●● ●● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 0.16 ● ● ●● ●● ● ●●● ● ●● ● ●● ● ● ● ● ●● ● ● climate impact ● ● ● ● ● ●● ● ● ● ● ●● ● ● Q ● ● ● ●● ● ● ● ● ● − ∆ ● ● ● ● ● ●● − ∆ ● ● ● E ● ● p basin impact ● P −0.2 −0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 −0.2 −0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 ∆W Maik Renner● Land use effects and climate impacts on evapotranspiration and catchment water balance Tharandter Klimaprotokolle - Band 18: Renner (2013) Herausgeber Institut für Hydrologie und Meteorologie Professur für Meteorologie Tharandter Klimaprotokolle http://tu-dresden.de/meteorologie Band 18 THARANDTER KLIMAPROTOKOLLE Band 18 Maik Renner Land use effects and climate impacts on evapotranspiration and catchment water balance Tharandt, Januar 2013 ISSN 1436-5235 Tharandter Klimaprotokolle ISBN 978-3-86780-368-7 Eigenverlag der Technischen Universität Dresden, Dresden Vervielfältigung: reprogress GmbH, Dresden Druck/Umschlag: reprogress GmbH, Dresden Layout/Umschlag: Valeri Goldberg Herausgeber: Christian Bernhofer und Valeri Goldberg Redaktion: Valeri Goldberg Institut für -

Beitrag Zur Kenntnis Der Steinfliegen Sachsens (Plecoptera)

© Entomologische Nachrichten und Berichte; downloadEntomologische unter www.biologiezentrum.at Nachrichten und Berichte, 41,1997/4 213 W. Joost, Gotha & R. K üttner , Schweikershain Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Steinfliegen Sachsens (Plecoptera) Zusammenfasssung Es wird ein kurzer Abriß zur Erforschungsgeschichte der Plecoptera in Sachsen gege ben, wobei besonders die Verdienste des Lehrers M ichael R ostock (1821-1893) gewürdigt werden. Für 49 Pleco- ptera-Arten liegen aus fast allen Landesteilen neue faunistische Daten vor. Von den 3435 determinierten Steinflie gen entfielen allein 997 Exemplare auf Leuctra nigra, die 28 % vom Gesamtfang repräsentieren. Für 17 in Sachsen seltene Arten werden Angaben zum Vorkommen und zur Ökologie mitgeteilt. Summary Contribution to the stoneflies (Plecoptera) of Saxony - A brief historical account of Plecoptera research in Saxony is presented, with emphasis on the merits of the teacher M ichael Rostock (1821-1893). New faunistical data for 49 Plecoptera species are published from almost all parts of the country. A total of 3435 stoneflies were identified, of which 997 specimens belong to Leuctra nigra, corresponding to 28% of the total catch. Data on occurence and ecology are presented for 17 species which are rare in Saxony. „Diese Thiere haben nur den Zweck, von anderen Thieren, namentlich Fischen, gefressen zu werden ... Das dies ihr einziger Zweck ist, soll damit nicht gesagt sein. Sie sollen, um einiges zu erwähnen, ein Glied sein in der grossen Kette der Schöpfung; sie sollen die Landschaft beleben, sie sollen dem Naturforscher Stoff geben zu seinen Studien etc “ M ichael Rostock (1879) 1 Einleitung Vielen Dank auch Herrn D ietrich B raasch , Potsdam, Die vorliegende Arbeit stellt Nachweise von sächsi für einige Fundortangaben zu seinen früheren Auf schen Steinfliegen von 1953-1995 zusammen. -

Io IW3) Historische Hochwasser Aus Dem Erzgebirge

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT DRESDEN Fakultät Bauingenieurwesen Institut für Wasserbau und Technische Hydromechanik Dresdner Wasserbauliche Mitteilungen, Heft 28 Bibliothek Wasser vn:i \.;iWvv:;-;t SäÖllotfaek T^fT:tS INSTITUT f-" f v-^: f^Mi 42S/ äiä/163B50 UND w.s^i?wiRii?:;;^T 06151 / 163758 TECHNiSiitE i^Ei.s.^T :,;. :..SiAr>T PETERSENSTH. 13, 84287 DARMSTAOT Reinhard Pohl Tal. 0 6? 61 /16 2143 • Fax • 18 32 43 iO IW3) Historische Hochwasser aus dem Erzgebirge Von der Gottleuba bis zur Mulde Bibliothek Wasser und Umwelt -CD4 .P.a.CrP Stadt) Dresden, im Mai 2004 Reinhard Pohl Historische Hochwasser aus dem Erzgebirge von der Gottleuba bis zur Mulde Inhaltsverzeichnis , Inhaltsverzeichnis / Einführung // Quellen zum llochwassergeschehen 13 Hochwässer, die mehrere Einzugsgebiete lies östlichen und mittleren Erzgebirges betrafen oder nicht genau lokalisiert werden konnten 19 Flüsse lies Osterzgebirges , 21 im direkten Einzugsgebiet der Elbe 21 Gottleuba , 21 13.12.1480 25 1533 25 15.11.1552 25 21.7.1560 25 1569 25 13.8.1573 25 2.8.1703 25 11.7.1750 26 25.6.1824 26 13.8.1837 26 30.-31.7. 1897 26 8.-9.7. 1927 27 13.5.1948 36 10.7.1954 36 22.-23.7.1957 36 5.-6.7.1958 37 Zehista 37 30.-31.7.1897 37 1927 37 22.-23.7.1957 37 Seidewitz 38 1533 38 28.5.1617 38 2.8.1703 38 1804 38 1858 38 31.7.1860 38 1865 38 1887 39 1891 39 30.-31.7.1897 39 8.-9.7.1927 39 7.7.1939 41 22.-23.7.1957 41 5.-6.7.1958 41 Bahrebach 42 Historische Hochwasser aus dem Erzgebirge 1957, 1958 42 Bahra 42 1670 42 117 1750 42 1804 42 1867 : 42 1880 42 13 5 1948 43 22-23 7 1957 43 43 1957 1958 43 44 15 11 1552 46 1609 47 1618 : 47 25 5 1679 47 1694 47 1701 47 2.8.1703 47 1709 . -

Vorderseite Karlsroute 2020 2.Qxd 05.06.2020 12:09 Uhr Seite 1

Vorderseite Karlsroute_2020_2.qxd05.06.202012:09UhrSeite1 2. Auflage/2.vydn/2ndedition07/2019Ð50.000Stck/kusó/pieces vydavatele./Reprinting andcopyingofanykindareprohibited.Hintstothepublisher.; geber./Reprodukce arozäiÞovnzakzno.DaläpÞipomnkyzaslejtenaadresu Nachdruck undVervielfltigungenjeglicherArtsindverboten.HinweiseandenHeraus- MEDIA, Sosa;Druck/vùtisk/print: Fotky pÞednazadnstrana/Photosfrontandback:123RFJacekChabraszewski,STUDIO2 Eibenstock undcore-consultGmbH&Co.KGDresden;FotosVorder-Rckseite/ Dresden ;englischebersetzung/anglickùpÞeklad/Englishtranslation:AdelheideWerk, pÞeklad/Czech translation:RolandGrahsberger,Perninkund setting: SACHSENKARTOGRAPHIEGmbH,Dresden;tschechischebersetzung/eskù lage/kartografie/basic maps:SACHSENKARTOGRAPHIEGmbH,Dresden;Satz/sazba/type- Accompanying projectsecretariat:core-consultGmbH&Co.KG,Dresden;Kartengrund- continuation oftheKarlsrouteÒ;BegleitendesProjektsekretariat/Projektovùsekretarit/ Dalä rozvojapokraovnKarlovystezkyÒ/ãKarlsrouteII-Furtherdevelopmentand ãKarlsroute II-WeiterentwicklungundFortfhrungderKarlsroute"/ãKarlovaStezka verband ãMuldentalradwegÒRathausplatz1,08309EibenstockimRahmendesProjektes Erarbeitet undherausgebenvon/zpracovalavydal/compiledandpublishedby:Zweck- Impressum/Impresum/Publication details: a dalsstÕecyklostezekvzpadnmKruänohoÞ Main routeandsecondaryroutesaswellthe Povrchtrasy/Roadsurface Krlovstv Streckenbelag rest ofthebicyclenetworkinWestErzgebirge Chemnitz -AueEibenstockNejdekKarlovyVary sowie brigesRadroutennetzWesterzgebirge „Panoramic tour“ Feeder Pr „Krus -

Aktuelle Fragen Des Hochwasserschutzes 1

Pegel Dresden / Elbe Vergleich der Hochwasserganglinien vom Sommer 2002 und Frühjahr 2006 Höchststand W = 940 cm am 17.08.02 2002 2006 900 Alarmstufe 1 Alarmstufe 2 800 Alarmstufe 4 700 Höchststand W = Alarmstufe 3 [cm] 600 749 cm am 04.04.06 Alarmstufe 2 500 400 Wasserstand Wasserstand Wasserstand Alarmstufe 1 300 200 100 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Zeit [d] Aktuelle Fragen des Hochwasserschutzes 1. Trierer Wasserwirtschaftsrechtlicher Gesprächskreis 22. August 2006 Sächsisches Staatsministerium für Umwelt und Landwirtschaft Autor: Herr Dallhammer Hochwasser 2002 bis 2006 im Jahrhundertvergleich Jahr Datum W Q 2002 17.08.02 940 4580 2003 06.01.03 669 2010 2004 08.02.04 406 888 2005 20.03.05 597 1600 2006 * 04.04.06 749 2590 Zeitreihe der jährlichen Hochwasserscheitelabflüsse an der Elbe 2002-2006 ( * ungeprüfte Rohdaten) Abb. 4.9: Zeitreihe der jährlichen Hochwasserscheitelabflüsse an der Elbe in Dresden (1890-2002) 7. Dezember 2007 Sächsisches Staatsministerium für Umwelt und Landwirtschaft Folie 2 Autor: Herr Dallhammer Delitzsch Torgau-Oschatz Hoyerswerda e S M ahl c u D h Niederschlesischer ld w e a Oberlausitzkreis r itz z r Dölln Riesa-Großenhain w e tLeipzig a s s l Muldentalkreis a s e E n Kamenz e h e ß i e a r e r e ß J G i r p o N e Vereinigte Mulde, Pleiße, Weiße Elster S ß e r W h Leipziger Land ac R e F b ö z re er d t ibe tz er i e s rge K Bautzen Görlitz r u M h itz e uld c en a ß e s Meißen Döbeln Elbe s L i i e e b e W l d ie l P r u u T a M p Dresden B r o o E e h b z lb u c G t e ri i s r a r t -

Vergleich Der Größten Hochwasser Im Muldegebiet

Vergleich der größten Hoch- wasser im Muldegebiet Schriftenreihe, Heft 18/2016 Schriftenreihe des LfULG, Heft XX/2016 | 1 Die größten Hochwasser im Einzugsgebiet der Mulde im meteorologisch- hydrologischen Vergleich Andreas Schumann, Björn Fischer, Uwe Büttner, Evelin Bohn, Petra Walther und Erhard Wolf Schriftenreihe des LfULG, Heft 18/2016 | 2 Inhalt 1 Einleitung ............................................................................................................................................................ 14 2 Beschreibung des Flussgebietes der Mulde .................................................................................................... 15 2.1 Lage und Abgrenzung .......................................................................................................................................... 15 2.2 Landschafts- und Naturräume .............................................................................................................................. 16 2.3 Geologie und Pedologie ....................................................................................................................................... 18 2.4 Flächennutzung .................................................................................................................................................... 23 2.5 Klimatische Verhältnisse ....................................................................................................................................... 24 2.6 Hydrologische Verhältnisse ................................................................................................................................. -

Jewels from Volcanoes a Journey Through 500 Million Years of Earth History

JEWELS FROM VOLCANOES A journey through 500 Million Years of Earth History Zuständig für die Durchführung der ELER-Förderung im Freistaat Sachsen ist das Staatsministerium für Energie, Klimaschutz, Umwelt und Land- wirtschaft, Referat Förderstrategie, ELER-Verwaltungsbehörde. Clicking this symbol on the top right corner of the double pages takes you back to the Index. Contents Welcome 3 The narrow gauge railway network of Mügeln and kaolin transport 30 Geopark Porphyrland 4 Glossen – living testimony of historic Travelling back in time – finding out why are loading and transport technology 31 we so rich in raw materials 6 Geoportal Mügeln Railway Station Supervolcanoes – Foundation of and China Clay Experience 32 the Geopark Porphyry Land 8 Clays for Ceramics in Wealth from rocks 10 the Künstlerhaus Schaddelmühle 33 Hills and towers 11 The Faïence and Stoneware Manufactory Hubertusburg 34 Geotopes – exciting places to understand geology 12 Ice Age discovery world in the Geopark Porphyry Land 36 Industrial culture – exploring industrial Drinking water production in the geopark 38 use of stones 13 Bad Lausick – traditional spa town since 1820 39 Unique and precious: “Rochlitz porphyry tuff“ 14 Castles and palaces in the Geopark Porphyry Land 40 The porphyry quarries on Rochlitz Hill and their owners 16 Geopark and Pleasure: hunting and fishing 43 Granite porphyry for the biggest monument in Europe 18 Geopark and Pleasure: fruit-growing 44 Basalt-Actien-Gesellschaft 21 Activities in the geopark 46 Trade Association Mineral Building Materials -

The Birth of an Empire of Two Churches : Church Property

The Birth of an Empire of Two Churches: Church Property, Theologians, and the League of Schmalkalden CHRISTOPHER OCKER ID THE CREATION OF PROTESTANT CHURCHES IN GERMANY during Luther’s generation follow someone’s intentions? Heiko Oberman, appealing to a medieval DLuther, portrays the reformer as herald of a dawning apocalypse, a monk at war with the devil, who expected God to judge the world and rescue Christians with no help from human institutions, abilities, and processes.1 This Luther could not have intended the creation of a new church. Dorothea Wendebourg and Hans-Jürgen Goertz stress the diversity of early evangelical movements. Goertz argues that anticlericalism helped the early Reformation’s gamut of spiritual, political, economic, and social trends to coalesce into moderate and radical groups, whereas Wendebourg suggests that the movements were only united in the judgment of the Counter Reformation.2 Many scholars concede this diversity. “There were very many different Reformations,” Diarmaid McCulloch has recently observed, aimed “at recreating authentic Catholic Christianity.”3 But some intention to form a new church existed, even if the intention was indirect. Scholars have identified the princely reaction to the revolting peasants of 1524–1525 as the first impetus toward political and institutional Protestantism.4 There was a 1Heiko A. Oberman, Die Wirkung der Reformation: Probleme und Perspektiven, Institut für Europäische Geschichte Mainz Vorträge 80 (Wiesbaden, 1987), 46; idem, Luther: Man between God and the Devil (New York, 1992), passim; idem, “Martin Luther zwischen Mittelalter und Neuzeit,” in Die Reformation: Von Wittenberg nach Genf (Göttingen, 1987), 189–207; Scott Hendrix, “‘More Than a Prophet’: Martin Luther in the Work of Heiko Oberman,” in The Work of Heiko A.