Química (2015) 26, 346---355

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valentine from a Telegraph Clerk to a Telegraph Clerk

Science Museum Group Journal Technologies of Romance: Valentine from a Telegraph Clerk ♂ to a Telegraph Clerk ♀: the material culture and standards of early electrical telegraphy Journal ISSN number: 2054-5770 This article was written by Elizabeth Bruton 10-08-2019 Cite as 10.15180; 191201 Discussion Technologies of Romance: Valentine from a Telegraph Clerk ♂ to a Telegraph Clerk ♀: the material culture and standards of early electrical telegraphy Published in Autumn 2019, Issue 12 Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191201 Keywords electrical telegraphy, poetry, scientific instruments, James Clerk Maxwell Valentine from A Telegraph Clerk ♂ to a Telegraph Clerk ♀, by JC Maxwell, 1860 The tendrils of my soul are twined With thine, though many a mile apart. And thine in close coiled circuits wind Around the needle of my heart. Constant as Daniell, strong as Grove. Ebullient throughout its depths like Smee, My heart puts forth its tide of love, And all its circuits close in thee. O tell me, when along the line From my full heart the message flows, What currents are induced in thine? One click from thee will end my woes. Through many an Ohm the Weber flew, And clicked this answer back to me; I am thy Farad staunch and true, Charged to a Volt with love for thee Component DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191201/001 Introduction In 1860, renowned natural philosopher (now referred to as a ‘scientist’ or, more specifically in the case of Clerk Maxwell, a ‘physicist’) James Clerk Maxwell wrote ‘Valentine from a Telegraph Clerk ♂ [male] to a Telegraph Clerk ♀ [female]’ (Harman, 2001).[1] The short poem was a slightly tongue-in-cheek ode to the romance of the electric telegraph littered with references to manufacturers of batteries used in electrical telegraphy around this time such as John Daniell, Alfred Smee, and William Grove and electrical units (now SI derived units) such as Ohm, Weber, Farad and Volt (Mills, 1995). -

Cavendish the Experimental Life

Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Gerd Graßhoff, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Klaus Thoden, Dirk Wintergrün. The Edition Open Access (EOA) platform was founded to bring together publi- cation initiatives seeking to disseminate the results of scholarly work in a format that combines traditional publications with the digital medium. It currently hosts the open-access publications of the “Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge” (MPRL) and “Edition Open Sources” (EOS). EOA is open to host other open access initiatives similar in conception and spirit, in accordance with the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the sciences and humanities, which was launched by the Max Planck Society in 2003. By combining the advantages of traditional publications and the digital medium, the platform offers a new way of publishing research and of studying historical topics or current issues in relation to primary materials that are otherwise not easily available. The volumes are available both as printed books and as online open access publications. They are directed at scholars and students of various disciplines, and at a broader public interested in how science shapes our world. Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach Studies 7 Studies 7 Communicated by Jed Z. Buchwald Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Bendix Düker, Caroline Frank, Beatrice Hermann, Beatrice Hilke Image Processing: Digitization Group of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover Image: Chemical Laboratory. -

History of Electric Light

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 76. NUMBER 2 HISTORY OF ELECTRIC LIGHT BY HENRY SGHROEDER Harrison, New Jersey PER\ ^"^^3^ /ORB (Publication 2717) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION AUGUST 15, 1923 Zrtie Boxb QSaftitnore (prcee BALTIMORE, MD., U. S. A. CONTENTS PAGE List of Illustrations v Foreword ix Chronology of Electric Light xi Early Records of Electricity and Magnetism i Machines Generating Electricity by Friction 2 The Leyden Jar 3 Electricity Generated by Chemical Means 3 Improvement of Volta's Battery 5 Davy's Discoveries 5 Researches of Oersted, Ampere, Schweigger and Sturgeon 6 Ohm's Law 7 Invention of the Dynamo 7 Daniell's Battery 10 Grove's Battery 11 Grove's Demonstration of Incandescent Lighting 12 Grenet Battery 13 De Moleyns' Incandescent Lamp 13 Early Developments of the Arc Lamp 14 Joule's Law 16 Starr's Incandescent Lamp 17 Other Early Incandescent Lamps 19 Further Arc Lamp Developments 20 Development of the Dynamo, 1840-1860 24 The First Commercial Installation of an Electric Light 25 Further Dynamo Developments 27 Russian Incandescent Lamp Inventors 30 The Jablochkofif " Candle " 31 Commercial Introduction of the Differentially Controlled Arc Lamp ^3 Arc Lighting in the United States 3;^ Other American Arc Light Systems 40 " Sub-Dividing the Electric Light " 42 Edison's Invention of a Practical Incandescent Lamp 43 Edison's Three-Wire System 53 Development of the Alternating Current Constant Potential System 54 Incandescent Lamp Developments, 1884-1894 56 The Edison " Municipal -

Back Matter (PDF)

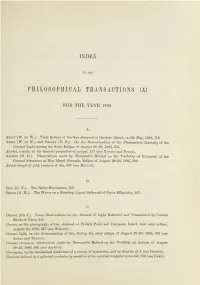

INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS (A) FOR THE YEAR 1894. A. Arc spectrum of electrolytic ,iron on the photographic, 983 (see Lockyer). B. Bakerian L ecture.—On the Relations between the Viscosity (Internal 1 riction) of Liquids and then Chemical Nature, 397 (see T iiorpe and R odger). Bessemer process, the spectroscopic phenomena and thermo-chemistry of the, 1041 IIarimo). C. Capstick (J. W.). On the Ratio of the Specific Heats of the Paraffins, and their Monohalogei.. Derivatives, 1. Carbon dioxide, on the specific heat of, at constant volume, 943 (sec ). Carbon dioxide, the specific heat of, as a function of temperatuie, ddl (mo I j . , , Crystals, an instrument of precision for producing monochromatic light of any desire. ua\e- eng », * its use in the investigation of the optical properties of, did (see it MDCCCXCIV.— A. ^ <'rystals of artificial preparations, an instrument for grinding section-plates and prisms of, 887 (see Tutton). Cubic surface, on a special form of the general equation of a, and on a diagram representing the twenty- seven lines on the surface, 37 (see Taylor). •Cables, on plane, 247 (see Scott). D. D unkeelky (S.). On the Whirling and Vibration of Shafts, 279. Dynamical theory of the electric and luminifei’ous medium, a, 719 (see Larmor). E. Eclipse of the sun, April 16, 1893, preliminary report on the results obtained with the prismatic cameras during the total, 711 (see Lockyer). Electric and luminiferous medium, a dynamical theory of the, 719 (see Larmor). Electrolytic iron, on the photographic arc spectrum of, 983 (see Lockyer). Equation of the general cubic surface, 37 (see Taylor). -

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town Cl740-Cl820

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town cl740-cl820 Neville Flavell PhD The Division of Adult Continuing Education University of Sheffield February 1996 Volume One THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF SHEFFIELD AND THE GROWTH OF THE TOWN cl740-c 1820 Neville Flavell February 1996 SUMMARY In the early eighteenth century Sheffield was a modest industrial town with an established reputation for cutlery and hardware. It was, however, far inland, off the main highway network and twenty miles from the nearest navigation. One might say that with those disadvantages its future looked distinctly unpromising. A century later, Sheffield was a maker of plated goods and silverware of international repute, was en route to world supremacy in steel, and had already become the world's greatest producer of cutlery and edge tools. How did it happen? Internal economies of scale vastly outweighed deficiencies. Skills, innovations and discoveries, entrepreneurs, investment, key local resources (water power, coal, wood and iron), and a rapidly growing labour force swelled largely by immigrants from the region were paramount. Each of these, together with external credit, improved transport and ever-widening markets, played a significant part in the town's metamorphosis. Economic and population growth were accompanied by a series of urban developments which first pushed outward the existing boundaries. Considerable infill of gardens and orchards followed, with further peripheral expansion overspilling into adjacent townships. New industrial, commercial and civic building, most of it within the central area, reinforced this second phase. A period of retrenchment coincided with the French and Napoleonic wars, before a renewed surge of construction restored the impetus. -

Philosophical Transactions (A)

INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS (A) FOR THE YEAR 1889. A. A bney (W. de W.). Total Eclipse of the San observed at Caroline Island, on 6th May, 1883, 119. A bney (W. de W.) and T horpe (T. E.). On the Determination of the Photometric Intensity of the Coronal Light during the Solar Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 363. Alcohol, a study of the thermal properties of propyl, 137 (see R amsay and Y oung). Archer (R. H.). Observations made by Newcomb’s Method on the Visibility of Extension of the Coronal Streamers at Hog Island, Grenada, Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 382. Atomic weight of gold, revision of the, 395 (see Mallet). B. B oys (C. V.). The Radio-Micrometer, 159. B ryan (G. H.). The Waves on a Rotating Liquid Spheroid of Finite Ellipticity, 187. C. Conroy (Sir J.). Some Observations on the Amount of Light Reflected and Transmitted by Certain 'Kinds of Glass, 245. Corona, on the photographs of the, obtained at Prickly Point and Carriacou Island, total solar eclipse, August 29, 1886, 347 (see W esley). Coronal light, on the determination of the, during the solar eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 363 (see Abney and Thorpe). Coronal streamers, observations made by Newcomb’s Method on the Visibility of, Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 382 (see A rcher). Cosmogony, on the mechanical conditions of a swarm of meteorites, and on theories of, 1 (see Darwin). Currents induced in a spherical conductor by variation of an external magnetic potential, 513 (see Lamb). 520 INDEX. -

Complete List of CHRISTMAS LECTURES

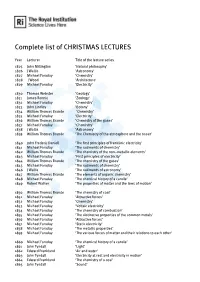

Complete list of CHRISTMAS LECTURES Year Lecturer Title of the lecture series 1825 John Millington ‘Natural philosophy’ 1826 J Wallis ‘Astronomy’ 1827 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1828 J Wood ‘Architecture’ 1829 Michael Faraday ‘Electricity’ 1830 Thomas Webster ‘Geology’ 1831 James Rennie ‘Zoology’ 1832 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1833 John Lindley ‘Botany’ 1834 William Thomas Brande ‘Chemistry’ 1835 Michael Faraday ‘Electricity’ 1836 William Thomas Brande ‘Chemistry of the gases’ 1837 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1838 J Wallis ‘Astronomy’ 1839 William Thomas Brande ‘The Chemistry of the atmosphere and the ocean’ 1840 John Frederic Daniell ‘The first principles of franklinic electricity’ 1841 Michael Faraday ‘The rudiments of chemistry’ 1842 William Thomas Brande ‘The chemistry of the non–metallic elements’ 1843 Michael Faraday ‘First principles of electricity’ 1844 William Thomas Brande ‘The chemistry of the gases’ 1845 Michael Faraday ‘The rudiments of chemistry’ 1846 J Wallis ‘The rudiments of astronomy’ 1847 William Thomas Brande ‘The elements of organic chemistry’ 1848 Michael Faraday ‘The chemical history of a candle’ 1849 Robert Walker ‘The properties of matter and the laws of motion’ 1850 William Thomas Brande ‘The chemistry of coal’ 1851 Michael Faraday ‘Attractive forces’ 1852 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1853 Michael Faraday ‘Voltaic electricity’ 1854 Michael Faraday ‘The chemistry of combustion’ 1855 Michael Faraday ‘The distinctive properties of the common metals’ 1856 Michael Faraday ‘Attractive forces’ 1857 Michael Faraday -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-41966-6 — the Victorian Palace of Science Edward J

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-41966-6 — The Victorian Palace of Science Edward J. Gillin Index More Information Index A Geological Manual,94 Albemarle Street, 68 A Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Albert, Prince, 160, 195 Natural philosophy,4 anti slavery, 158 A rudimentary treatise on clock and at the British Association, 68 watchmaking, 245 Michael Faraday, 184 Aberdeen, University of, 29 Alison, Archibald, 50–52 abolition of slavery, 3, 91, 158 on architecture, 51, 52 Acland, Thomas, 198 on Parliament, 51 acoustics, 30, 31, 56, 58, 59, 84, 140, 143 on utility, 52 Adams, Robert, 116, 117 political views, 51 Admiralty, 224 All Saint’s Church, Babbacombe, 120 Airy, George Biddell, 203, 216, 218, 220, All Souls College, Oxford, 95 232, 233, 238, 244, 252, 253, 256, An Introduction to the Study of Chemical 262, 263, 267, 268, 271 Philosophy,99 accuracy, 214, 224, 225, 237 Anderson, John Wilson, 131, 132 as Astronomer Royal, 221–23 Anglican, 6, 244 at Cambridge, 220 architecture, 109 at Greenwich, 216, 217, 221–23, 224, Broad Church, 6 225, 231 Cornwall, 188 authority over Edward John Dent, 250–51 geology, 107 career, 220 governance, 51 compass deviation, 221 High Church, 47, 106 dispute with Benjamin Vulliamy, 234–38 John Frederic Daniell, 99 Edmund Beckett Denison, 216 science, 5 Edward John Dent, 219, 225–26, 237 theology, 4 galvanic regulation, 217 universities, 125 galvanic time system, 227, 228–32, Anning, Mary, 91 238–44, 252, 253, 258 Ansted, David, 266 Greenwich time, 217 Anston stone, 102, 115, 117, 118, 265, Greenwich -

BENJAMIN SILLIMAN JR.’S 1874 PAPERS: AMERICAN CONTRIBUTIONS to CHEMISTRY 22 Martin D

BULLETIN FOR THE HISTORY OF CHEMISTRY Division of the History of Chemistry of the American Chemical Society VOLUME 36 Number 1 2011 Celebrate the International Year of Chemistry with HIST and ACS BULLETIN FOR THE HISTORY OF CHEMISTRY VOLUME 36, CONTENTS NUMBER 1 CHAIRS’ LETTER 1 EDITOR’S LETTER 2 “NOTITIA CŒRULEI BEROLINENSIS NUPER INVENTI” ON THE 300th ANNIVERSARY OF THE FIRST PUBLICATION ON PRUSSIAN BLUE 3 Alexander Kraft, Gesimat GmbH, Berlin PHYSICAL CHEMISTRY BEFORE OSTWALD: THE TEXTBOOKS OF JOSIAH PARSONS COOKE 10 William B. Jensen, University of Cincinnati BENJAMIN SILLIMAN JR.’S 1874 PAPERS: AMERICAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO CHEMISTRY 22 Martin D. Saltzman, Providence College THE RISE AND FALL OF DOMESTIC CHEMISTRY IN HIGHER EDUCATION IN ENGLAND DURING THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY 35 Marelene Rayner-Canham and Geoff Rayner-Canham Grenfell Campus, Memorial University, Corner Brook, Newfoundland DENISON-HACKH STRUCTURE SYMBOLS: A FORGOTTEN EPISODE IN THE TEACHING OF ORGANIC CHEMISTRY 43 William B. Jensen, University of Cincinnati LETTER: Vedic Hinduism and the Four Elements 51 BOOK REVIEWS Pharmacy and Drug Lore in Antiquity: Greece, Rome, Byzantium 52 Materials and Expertise in Early Modern Europe 54 The Historiography of the Chemical Revolution: Patterns of Interpretatrion in the History of Science 56 Much Ado about (Practically) Nothing: A History of the Noble Gases 57 The Poisoner’s Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine in Jazz Age New York 58 Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 36, Number 1 (2011) 1 CHAIRS’ LETTER Dear Fellow HIST Members, Readers, and Friends of the Bulletin for the History of Chemistry, We, the undersigned Chairs, past and current, of the Division of History of Chemistry of the American Chemical Society, along with our Secretary-Treasurer for the last 16 years, join our entire community in acknowledging our gratitude to Paul R. -

Columbium and Tantalum

Rediscovery of the Elements Columbium and Tantalum Figure 2. Hatchett’s coach-making business was located at 121 Long Acre III (N51° 30.76 W00° 07.52). Charles spent his youth in Belle Vue in Chelsea (owned by his father) and then repurchased the home for his final James L. Marshall, Beta Eta 1971, and years (91-92 Virginia R. Marshall, Beta Eta 2003, Cheyne Walk; N51° 28.92 W00° 10.45). Department of Chemistry, University of Charles Hatchett’s North Texas, Denton, TX 76203-5070, first home after his marriage was at the Lower Mall in Hammersmith at an address today unknown; this [email protected] area was bombed in World War II and is now occupied by Furnival Gardens (N51° 29.42 W00° 13.99); this is where he discovered columbium. Also in Hammersmith may be found today at Hop Poles Inn (17-19 Charles Hatchett (1765–1847), a prosperous King Street, N51° 29.56 W00° 13.55), a favorite haunt of Charles Hatchett. In mid-life his home was London coach-builder and avocational Mount Clare (1808–1819) at Minstead Gardens, Roehampton (N51° 27.11 W00° 15.04). chemist, discovered columbium (niobium) in 1801. The following year, Anders Gufstaf Charles Hatchett 1 (Figure 2) was born at his merit his election to the Royal Society. His work Ekeberg (1767–1813), professor of chemistry at father’s carriage manufactory on Long Acre with bones and shells3b first determined the dif- the University of Uppsala, Sweden, discovered (Figure 3). Charles, being the only son, had ferent compositions of bones and teeth (mostly tantalum. -

Charles Hatchett: the Discoverer of Niobium

Educación Química (2015) 26, 346---355 educación Química www.educacionquimica.info TO GET RID OF ITS DUST Charles Hatchett: The discoverer of niobium Jaime Wisniak Department of Chemical Engineering, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva 84105, Israel Received 19 July 2014; accepted 25 September 2014 Available online 11 August 2015 KEYWORDS Abstract To Charles Hatchett (1765---1847), a self-educated scientist and first class analytical Bitumen; chemist, we owe the discovery of niobium, the analysis of a series of important minerals and Bones; animal substances such as shells, bones, dental enamel, a detailed study of bitumens, the Columbium; separation of an artificial tanning material from mineral and animal sources. Gold coins; All Rights Reserved © 2015 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Química. Lac; This is an open access item distributed under the Creative Commons CC License BY-NC-ND 4.0. Molybdenum; Niobium; Shells; Zoophites PALABRAS CLAVE Charles Hatchett: el descubridor del niobio Bitúmenes; Huesos; Resumen A Charles Hatchett (1765---1847), un científico autodidacta y hábil químico analítico, Columbio; le debemos el descubrimiento del niobio, el análisis de minerales importantes y de substancias animales como conchas, huesos y esmalte dental, un detallado estudio de los bitúmenes, la Monedas de oro; Lac; separación de taninos artificiales de fuentes minerales y animales, etc. Molibdeno; Derechos Reservados © 2015 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Química. Niobio; Este es un artículo de acceso abierto distribuido bajo los términos de la Licencia Creative Conchas; Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Zoofitas Life and career (Barrow, 1849; Coley, 2004; Griffith et al., 2003; Walker, 1862; Weeks, 1938) E-mail address: [email protected] Charles Hatchett was born at Long Acre, London, on 2 Jan- Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional uary 1765, the only child of John (1729---1806) and Elizabeth Autónoma de México. -

Back Matter (PDF)

[ 229 • ] INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS, S e r ie s B, FOR THE YEAR 1897 (YOL. 189). B. Bower (F. 0.). Studies in the Morphology of Spore-producing Members.— III. Marattiaceae, 35. C Cheirostrobus, a new Type of Fossil Cone (Scott), 1. E. Enamel, Tubular, in Marsupials and other Animals (Tomes), 107. F. Fossil Plants from Palaeozoic Rocks (Scott), 1, 83. L. Lycopodiaceae; Spencerites, a new Genus of Cones from Coal-measures (Scott), 83. 230 INDEX. M. Marattiaceae, Fossil and Recent, Comparison of Sori of (Bower), 3 Marsupials, Tubular Enamel a Class Character of (Tomes), 107. N. Naqada Race, Variation and Correlation of Skeleton in (Warren), 135 P. Pteridophyta: Cheirostrobus, a Fossil Cone, &c. (Scott), 1. S. Scott (D. H.). On the Structure and Affinities of Fossil Plants from the Palaeozoic Ro ks.—On Cheirostrobus, a new Type of Fossil Cone from the Lower Carboniferous Strata (Calciferous Sandstone Series), 1. Scott (D. H.). On the Structure and Affinities of Fossil Plants from the Palaeozoic Rocks.—II. On Spencerites, a new Genus of Lycopodiaceous Cones from the Coal-measures, founded on the Lepidodendron Spenceri of Williamson, 83. Skeleton, Human, Variation and Correlation of Parts of (Warren), 135. Sorus of JDancea, Kaulfxissia, M arattia, Angiopteris (Bower), 35. Spencerites insignis (Will.) and S. majusculus, n. sp., Lycopodiaceous Cones from Coal-measures (Scott), 83. Sphenophylleae, Affinities with Cheirostrobus, a Fossil Cone (Scott), 1. Spore-producing Members, Morphology of.—III. Marattiaceae (Bower), 35. Stereum lvirsutum, Biology of; destruction of Wood by (Ward), 123. T. Tomes (Charles S.). On the Development of Marsupial and other Tubular Enamels, with Notes upon the Development of Enamels in general, 107.