Customs and Traditions, Cures and Charms, Fairies and Phantoms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Susan Shelton Mural Imagery Key Top Section

“Nurturing the Dream” By Susan Shelton Mural Imagery Key Top Section: The quotes reflect the overall theme of the mural: the importance of finding a balance between the work we do as students, workers, activists, and caregivers, and the time needed for reflection, nourishment of the spirit and restoration of strength. The large rectangular tiles on pillars A, B, C, D are inspired by Wangari Maathai’s “I Will be a Hummingbird” story. This folk tale poignantly illustrates the importance of doing one’s best, no matter how insignificant our efforts may feel at times, in the face of a seemingly insurmountable task. Pillars: The mural pillars showcase the conceptual and artistic participation of the students and staff of the Student Community Center, and other members of the university community, who were invited to contribute their suggestions for the imagery featured, and who also participated in painting the individual tiles. The tiles represent the various identities, paths, goals, causes and struggles of the students: academic, social, personal and political. Pillar A: 1. World View: North and South America 2. Wi-Fi Symbol/Connectivity 3. Power Symbol in the Digital Age 4. Hands Holding Seedling: Cultivating Hope/Justice/Stewardship 5. Filipino Sun 6. Irish Symbol: Love, Loyalty and Friendship 7. Love, Pride and Celebration of African Heritage 8. Lotus: Ancient Asian Polyvalent Symbol 9. Raised Fist with Olive Branch: Nonviolent Protest/Activism 10. Study of Astronomy/Astrophysics 11. Study of Enology/Viticulture 12. Study of Music/Music Bringing People Together 13. McNair Scholarship Program 14. Salaam: Peace/Peace Be With You (written in Amharic) 15. -

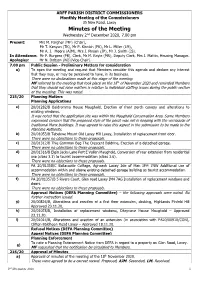

02.12.20 Draft Minutes

ARFF PARISH DISTRICT COMMISSIONERS Monthly Meeting of the Commissioners 35 New Road, Laxey Minutes of the Meeting Wednesday 2nd December 2020, 7.00 pm Present: Mrs M. Fargher (MF) (Chair), Mr T. Kenyon (TK), Mr P. Kinnish (PK), Mr L. Miller (LM), Mr A. J. Moore (AJM), Mrs J. Pinson (JP), Mr J. Smith (JS). In Attendance: Mr P. Burgess (PB), Clerk, Mr M. Royle (MR), Deputy Clerk, Mrs J. Mattin, Housing Manager. Apologies: Mr N. Dobson (ND)(Vice-Chair). 7.00 pm Public Session - Preliminary Matters for consideration a) To open the meeting and request that Members consider this agenda and declare any interest that they may, or may be perceived to have, in its business. There were no declarations made at this stage of the meeting. MF referred to the meeting that took place on the 18th of November 2020 and reminded Members that they should not raise matters is relation to individual staffing issues during the public section of the meeting. This was noted. 215/20 Planning Matters Planning Applications a) 20/01282/B Baldromma House Maughold, Erection of front porch canopy and alterations to existing windows. It was noted that the application site was within the Maughold Conservation Area. Some Members expressed concern that the proposed style of the porch was not in keeping with the vernacular of traditional Manx buildings. It was agreed to raise this aspect in the submission to be made to the Planning Authority. b) 20/01053/B Tebekwe Mount Old Laxey Hill Laxey, Installation of replacement front door. There were no objections to these proposals. -

The Language of Flowers Is Almost As Ancient and Universal a One As That of Speech

T H E LANGUAGE OF FLOWERS; OR, FLORA SYMBOLIC A. INCLUDING FLORAL POETRY, ORIGINAL AND SELECTED. BY JOHN INGRAM. “ Then took he up his garland, And did shew what every flower did signify.” Philaster. Beaumont and Fletcher. WITH ORIGINAL ILLUSTRATIONS, PRINTED IN COLOURS BY TERRY. LONDON AND NEW YORK: FREDERICK WARNE AND CO. 1887. vA^tT Q-R 7 SO XSH mi TO Eliza Coo k THIS VOLUME IS AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED BY HER FRIEND THE AUTHOR. o Preface. j^IIE LANGUAGE OF FLOWERS has probably called forth as many treatises in explanation of its few and simple rules as has any other mode of communicating ideas; but I flatter myself that this book will be found to be the most complete work on the subject ever published—at least, in this country. I have thoroughly sifted, condensed, and augmented the productions of my many predecessors, and have endeavoured to render the present volume in every re¬ spect worthy the attention of the countless votaries which this “ science of sweet things ” attracts ; and, although I dare not boast that I have exhausted the subject, I may certainly affirm that followers will find little left to glean in the paths that I have traversed. As I have made use of the numerous anecdotes, legends, and poetical allusions herein contained, so Preface. VI have I acknowledged the sources whence they came. It there¬ fore only remains for me to take leave of my readers, with the hope that they will pardon my having detained them so long over a work of this description , but “Unheeded flew the hours, For softly falls the foot of Time That only treads on flowers.” J. -

Manx National Heritage Sites Information

Historic Buildings Architect/Surveyor Thornbank, Douglas: Architects rendering for restoration of Baillie-Scott House owned by MNH (Horncastle:Thomas) Information for Applicants Manx National Heritage Historic Buildings Architect/Surveyor Our Organisation Manx National Heritage (MNH) is the trading name given to the Manx Museum and National Trust. The Trust was constituted in 1886 with the purpose of creating a national museum of Manx heritage and culture and has grown steadily in scope and reach and it is now the Islands statutory heritage agency. MNH exists to take a lead in protecting, conserving, making accessible and celebrating the Island’s natural and cultural heritage for current and future generations whilst contributing to the Island’s prosperity and quality of life MNH is a small organisation sponsored but operating at arm’s length from the Isle of Man Government. Our small properties management team is responsible for thirteen principle sites of historic and landscape significance, an array of field monuments and around 3000 acres of land. MNH welcomes around 400,000 visits to its properties every year and is also home to the National Museum, the National Archives and the National Art Gallery. Our Vision, principles and values MNH’s vision is “Securing the Future of Our Past”. Underpinning this vision are key principles and values which guide everyone who works for the organisation as they conduct their core business and their decision-making. Being led by and responsive to our visitors and users Working in collaboration -

Provincial Symbols and Honours Chap

1989 PROVINCIAL SYMBOLS AND HONOURS CHAP. 10 PROVINCIAL SYMBOLS AND HONOURS ACT CHAPTER 10 Assented to April 21,1989. Contents PARTI PROVINCIAL SYMBOLS Section Section 1. Coatof Anna of the Province 6. Bird emblem 2. Representation of government 7. British Columbia Tartan authority 8. Use of tartan 3. Floral emblem 9. Regulations 4. Mineral emblem 10. Offence 5. Tree emblem 11. Misuse of Provincial symbol PART 2 PROVINCIAL HONOURS 12. Interpretation 17 Appointments 13. Order of British Columbia 18. Privileges of members 14. Advisory council 19. British Columbia Medal of Good Citizenship 15. Recommendation and rules 20. Regulations 16. Nominations 21. Repeal HER MAJESTY, by and with the advice and consent of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of British Columbia, enacts as follows: PART 1 PROVINCIAL SYMBOLS Coat of Arms of the Province 1.(1) The Coat of Arms of the Province is the Shield of Arms with Motto granted by Royal Warrant of King Edward VII on March 31, 1906, as augmented and granted by Royal Warrant of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, in Vancouver on October 15,1987. '2) No person, other than the Lieutenant Governor, a member of the Executive Council, a member of the Legislative Assembly or a judge of the Supreme Court, a County Court or the Provincial Court, shall, without the permission of the Provincial Secretary, assume, display or use the Coat of Arms of the Province or a design so closely resembling it as to be likely to deceive. Representation of government authority 2. (1) No person or organization shall assume, display or use a name, title or device that indicates or that is reasonably susceptible of the interpretation that the person or organization has authority from the government to do so or is exercising a function of the 33 CHAP. -

Holiday 2016 Mahanoy Area Middle School Christmas Merry

Paw Print Holiday 2016 Mahanoy Area Middle School Christmas Merry by Mara Wall Paw Print can also be viewed at mabears.net. Click on “district” Paw Print Holiday 2016 Mahanoy Area Middle School Favorite Christmas Traditions By: Desiree Hernandez, Hannah Mahmod, Hailey Heffilfinger, Mariah Hernandez We interviewed fifth, sixth and elementary teachers . was little and her dog named Shamrock when she was We interviewed Mr. Zack from the 5th grade. We inter- in second grade! That is how Ms. Linchorst feels about viewed Miss Linchorst who is filling in for Mrs. Gola- Christmas! noski. From elementary, Ms. Schlegle. We interviewed Finally, we interviewed elementary music teacher, them about their favorite holi- Miss Schlegel. Her favorite days and why they are their fa- holiday is Christmas. Miss vorite holidays. Schlegel`s favorite holiday is First up is Mr. Zack. His favor- Christmas because she gets to ite holiday is Christmas! This is spend time with her extended because he gets to spend time family. Every family has a with his family and gives pres- tradition for Christmas or ents to his amazing son. One Christmas Eve. Miss Schle- of his favorite traditions from gel’s tradition on Christmas when he was little was opening Eve is that the whole family one gift on Christmas Eve. All opens a present. We asked her of their gifts would be a pair of what was the best present she matching pajamas. They would ever got but she didn’t have wear them that night! That is one. So we asked her about what Mr Zack feels about his the weirdest gift she ever re- favorite holiday. -

Chrysanthemum Morifolium Ramat) Cv

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2020) 9(9): 3283-3288 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 9 Number 9 (2020) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2020.909.407 Effect of Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium Level on Morphological Characteristics of Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat) cv. Bidhan Madhuri S. K. Senapati*, T. K. Das and G. Pandey Department of Floriculture & Landscaping, College of Agriculture, Orissa University of Agriculture and Technology, Bhubaneswar-751003, Odisha, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT An investigation entitled Effect of nutrient management in chrysanthemum K e yw or ds (Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat cv. BidhanMadhuri) was carried out at BTCC, OUAT, Bhubaneswar during winter 2017-18. The experiment was laid out in randomized Chrysanthemum, block design (RBD) with comprising of eleven number of treatment combinations having Spray, Vegetative different combinations of N, P and K fertilizers (Kg/ha) which was replicated thrice in attributes, Height RBD. Among all the treatment, T having a fertilizer combinations of N=120, P=125, 10 K=140 Kg/ha i.e. the optimum dose of fertilizer higher than that of the RDF (N=100 Article Info ,P=125, K=100 Kg/ha) found to be effective in producing luxuriant and effective vegetative attributes i.e. maximum plant height (66.253cm), East-West spread (34.333cm), Accepted: 24 August 2020 North-South spread (32.526cm) while in case of number of spray per plant , treatment T9 Available Online: having a fertilizer combinations of N=120, P=125, K=120 Kg/ha was found more 10 September 2020 promising. -

List of National Animals from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

List of national animals From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This is a list of national animals. National animals Country Name of animal Scientific name Pictures Ref. Afghanistan Snow leopard Panthera uncia [1] Angola Red-crested turaco (national bird) Tauraco erythrolophus [2] Anguilla Zenaida dove Zenaida aurita [3] Fallow deer (national animal) Dama dama [4] Antigua and Barbuda Frigate (national bird) Fregata magnificens [4] Hawksbill turtle (national sea creature) Eretmochelys imbricata [4] Algeria Fennec fox Vulpes zerda [5] Argentina Rufous hornero Furnarius rufus [6] Red kangaroo (national animal) Macropus rufus [7] Australia Emu (national bird) Dromaius novaehollandiae [8] Azerbaijan Karabakh horse Equus ferus caballus [9] Royal Bengal tiger (national animal) Panthera tigris tigris [10] [10] Bangladesh Magpie robin (national bird) Copsychus saularis Ilish (national fish) Tenualosa ilisha [10] Belarus European bison Bison bonasus [11] Belize Baird's tapir Tapirus bairdii [11][12] Belgium Lion (heraldic Leo Belgicus) Panthera leo [13] Druk Mythical [14] Bhutan Takin Budorcas taxicolor [15] Cambodia Kouprey Bos sauveli [16] North American beaver (national animal) Castor canadensis [17][18] Canada Canadian horse (national horse) Equus ferus caballus [18] Democratic Republic of Okapi Okapia johnstoni [11] the Congo Colombia Andean condor Vultur gryphus [19] Yigüirro (national bird) Turdus grayi [20] Costa Rica White-Tailed Deer (national animal) Odocoileus virginianus [21] West Indian manatee (national aquatic animal) Trichechus manatus -

June/July 2016 American Institute of Floral Designers

Bi-Monthly Newsletter of the June/July 2016 American Institute of Floral Designers Hot Town, Summer in the City 2016 Symposium "Inspiration" is only weeks away! e can't possibly summarize all that is about to happen in just a few weeks when floral designers from all around the world will take over the OC! So here are a few highlights to get you excited: WHands on classes are back by popular demand! After a successful launch of the hands on workshops at last year's Symposium, we brought them back and they are better than ever! Carol Caggiano AIFD, PFCI, CFD will present "Balance in Design...the Key to Success," Beth O’Reilly AIFD, CFD is instructing "Trend Forward: Tips and Tricks for Trendy Brides," "Inspiring Wonders" will be presented by Deb Schwarze AIFD, CFD, and "A Key to Wow!” will feature Frank Feysa AIFD, PFCI, CFD. These workshops are added a la carte to your registration. Onsite registration will be available but these workshops are already selling out so don't wait, register for them now. Eleven main stage design programs means 11 chances to learn and see the latest trends and techniques you need to take your designs to a whole new level! Two day Partners' Expo = more time to meet and mingle with the industry's leading companies. The annual Partners’ Expo is being expanded from the traditional half-day of exciting opportunities to see the new products and services offered by our partners to two half-day sessions. More time to shop and get your hands and eyes on the newest products you use. -

Public Minutes Present:, Mr J James (Chairman), Mr G Pearce-White (Vice Chairman), , Mrs S Jones, Mr P Kinnish, in Attendance: Mr P

LAXEY VILLAGE COMMISSIONERS Monthly Meeting Wednesday 7th March 2012, 6.45pm Public Minutes Present:, Mr J James (Chairman), Mr G Pearce-White (Vice Chairman), , Mrs S Jones, Mr P Kinnish, In Attendance: Mr P. Burgess (Clerk)., Mr Steve Taggart, Apologies: Mr S Haddock, Mr P Hill Deputy Clerk. 127/11 Guest Speaker – Mr Steve Taggart – Department of Infrastructure Waste Management. To speak to the Commissioners and answer questions on recycling. JJ welcomed ST to the meeting. A discussion took place with reference to the proposal to place a recycling node at the end of Mines Road for a period of 6 months. SJ advised there had been a number of objections to this proposal. ST pointed out that the unit was a piece of street furniture and not the 1100 litre wheelie bins as located at the 3 recycling centres in the village. A discussion took place reference alternative locations for the trial including Ard Reayrt. The Commissioners resolved to investigate if Minorca Crescent was suitable for the Recycling Node. An informative discussion took place with ST PB briefing the Commissioners on the Curb side recycling scheme currently running in Douglas and Braddan, and circulated a graphs showing IoM Household Waste Composition following a waste audit in 2006, and waste survey carried out in 2008 and 2010. Discussions took place reference the volumes of waste produced by Laxey Households, the Clerk advised the current average was 728kg per annum, with similar figures for Lonan and Maughold . The Clerk also advised that information obtained from Onchan Commissioners indicated an average of 1128kg per household per annum, 400kg more that Laxey, and this was with curb side recycling in Onchan, ST suggested the figures for Douglas and Braddan may be higher. -

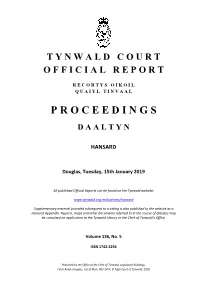

P R O C E E D I N G S

T Y N W A L D C O U R T O F F I C I A L R E P O R T R E C O R T Y S O I K O I L Q U A I Y L T I N V A A L P R O C E E D I N G S D A A L T Y N HANSARD Douglas, Tuesday, 15th January 2019 All published Official Reports can be found on the Tynwald website: www.tynwald.org.im/business/hansard Supplementary material provided subsequent to a sitting is also published to the website as a Hansard Appendix. Reports, maps and other documents referred to in the course of debates may be consulted on application to the Tynwald Library or the Clerk of Tynwald’s Office. Volume 136, No. 5 ISSN 1742-2256 Published by the Office of the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas, Isle of Man, IM1 3PW. © High Court of Tynwald, 2019 TYNWALD COURT, TUESDAY, 15th JANUARY 2019 Present: The President of Tynwald (Hon. S C Rodan) In the Council: The Attorney General (Mr J L M Quinn QC), Miss T M August-Hanson, Mr D C Cretney, Mr T M Crookall, Mr R W Henderson, Mrs M M Maska, Mrs K A Lord-Brennan, Mrs J P Poole-Wilson and Mrs K Sharpe with Mrs J Corkish, Third Clerk of Tynwald. In the Keys: The Speaker (Hon. J P Watterson) (Rushen); The Chief Minister (Hon. R H Quayle) (Middle); Mr J R Moorhouse and Hon. -

Living Bicentennial Floral Designs

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange SDSU Extension Fact Sheets SDSU Extension 1975 Living Bicentennial Floral Designs Cooperative Extension South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/extension_fact Recommended Citation South Dakota State University, Cooperative Extension, "Living Bicentennial Floral Designs" (1975). SDSU Extension Fact Sheets. 422. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/extension_fact/422 This Fact Sheet is brought to you for free and open access by the SDSU Extension at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in SDSU Extension Fact Sheets by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Historic, archived document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. SDSU ® Extension For current policies and practices, contact SDSU Extension \i\Tebsite: extension.sdstate.edu Phone: 605-688-4 792 Email: [email protected] SDSU Extension is an equal opportunity provider and employer in accordance with the nondiscrimination policies of South Dakota State University, the South Dakota Board of Regents and the United States Department of Agriculture. L iving B □ @®m:i~®m:im:i □ @~ -4- F Ioral D esigns South Dakota 1976 MT. RUSHMORE-SHRINE OF DEMOCRACY JUSA BICENTENNIAL FOCAL POINT Cooperative Extension Service South Dakota State University U.S. Department of Agriculture are to be grown. When growing annuals in ground beds, the soil should be prepared to a depth of 6-8 inches.