Commonlit | the Talking Skull

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Can I Learn from a Skull? Animal Skulls Have Evolved for Millions of Years to Protect Vertebrate’S Brains and Sensory Organs

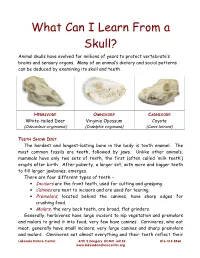

What Can I Learn From a Skull? Animal skulls have evolved for millions of years to protect vertebrate’s brains and sensory organs. Many of an animal’s dietary and social patterns can be deduced by examining its skull and teeth. HERBIVORE OMNIVORE CARNIVORE White-tailed Deer Virginia Opossum Coyote (Odocoileus virginianus) (Didelphis virginiana) (Canis latrans) TEETH SHOW DIET . The hardest and longest-lasting bone in the body is tooth enamel. The most common fossils are teeth, followed by jaws. Unlike other animals, mammals have only two sets of teeth, the first (often called ‘milk teeth’) erupts after birth. After puberty, a larger set, with more and bigger teeth to fill larger jawbones, emerges. There are four different types of teeth – • Incisors are the front teeth, used for cutting and grasping. • Canines are next to incisors and are used for tearing. • Premolars , located behind the canines, have sharp edges for crushing food. • Molars , the very back teeth, are broad, flat grinders. Generally, herbivores have large incisors to nip vegetation and premolars and molars to grind it into food; very few have canines. Carnivores, who eat meat, generally have small incisors, very large canines and sharp premolars and molars. Omnivores eat almost everything and their teeth reflect their Lakeside Nature Center 4701 E Gregory, KCMO 64132 816-513-8960 www.lakesidenaturecenter.org preferences; they have all four types of teeth. In fact, if you’d like to see an excellent example of an omnivore’s teeth, look in the mirror. EYE PLACEMENT IDENTIFIES PREDATORS . Carnivores generally have large eyes, placed so that the eyes look forward and the areas of vision of the two eyes overlap. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

6. the Pharynx the Pharynx, Which Forms the Upper Part of the Digestive Tract, Consists of Three Parts: the Nasopharynx, the Oropharynx and the Laryngopharynx

6. The Pharynx The pharynx, which forms the upper part of the digestive tract, consists of three parts: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx and the laryngopharynx. The principle object of this dissection is to observe the pharyngeal constrictors that form the back wall of the vocal tract. Because the cadaver is lying face down, we will consider these muscles from the back. Figure 6.1 shows their location. stylopharyngeus suuperior phayngeal constrictor mandible medial hyoid bone phayngeal constrictor inferior phayngeal constrictor Figure 6.1. Posterior view of the muscles of the pharynx. Each of the three pharyngeal constrictors has a left and right part that interdigitate (join in fingerlike branches) in the midline, forming a raphe, or union. This raphe forms the back wall of the pharynx. The superior pharyngeal constrictor is largely in the nasopharynx. It has several origins (some texts regard it as more than one muscle) one of which is the medial pterygoid plate. It assists in the constriction of the nasopharynx, but has little role in speech production other than helping form a site against which the velum may be pulled when forming a velic closure. The medial pharyngeal constrictor, which originates on the greater horn of the hyoid bone, also has little function in speech. To some extent it can be considered as an elevator of the hyoid bone, but its most important role for speech is simply as the back wall of the vocal tract. The inferior pharyngeal constrictor also performs this function, but plays a more important role constricting the pharynx in the formation of pharyngeal consonants. -

The Skull O Neurocranium, Form and Function O Dermatocranium, Form

Lesson 15 ◊ Lesson Outline: ♦ The Skull o Neurocranium, Form and Function o Dermatocranium, Form and Function o Splanchnocranium, Form and Function • Evolution and Design of Jaws • Fate of the Splanchnocranium ♦ Trends ◊ Objectives: At the end of this lesson, you should be able to: ♦ Describe the structure and function of the neurocranium ♦ Describe the structure and function of the dermatocranium ♦ Describe the origin of the splanchnocranium and discuss the various structures that have evolved from it. ♦ Describe the structure and function of the various structures that have been derived from the splanchnocranium ♦ Discuss various types of jaw suspension and the significance of the differences in each type ◊ References: ♦ Chapter: 9: 162-198 ◊ Reading for Next Lesson: ♦ Chapter: 9: 162-198 The Skull: From an anatomical perspective, the skull is composed of three parts based on the origins of the various components that make up the final product. These are the: Neurocranium (Chondocranium) Dermatocranium Splanchnocranium Each part is distinguished by its ontogenetic and phylogenetic origins although all three work together to produce the skull. The first two are considered part of the Cranial Skeleton. The latter is considered as a separate Visceral Skeleton in our textbook. Many other morphologists include the visceral skeleton as part of the cranial skeleton. This is a complex group of elements that are derived from the ancestral skeleton of the branchial arches and that ultimately gives rise to the jaws and the skeleton of the gill -

Metastatic Skull Tumours: Diagnosis and Management Mitsuya K, Nakasu Y European Association of Neurooncology Magazine 2014; 4 (2) 71-74

Volume 4 (2014) // Issue 2 // e-ISSN 2224-3453 European Association of NeuroOncology Magazine Neurology · Neurosurgery · Medical Oncology · Radiotherapy · Paediatric Neuro- oncology · Neuropathology · Neuroradiology · Neuroimaging · Nursing · Patient Issues Metastatic Skull Tumours: Diagnosis and Management Mitsuya K, Nakasu Y European Association of NeuroOncology Magazine 2014; 4 (2) 71-74 Homepage www.kup.at/ journals/eano/index.html Online Database Featuring Author, Key Word and Full-Text Search Member of the THE EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF NEUROONCOLOGY Indexed in EMBASE Krause & Pachernegg GmbH . VERLAG für MEDIZIN und WIRTSCHAFT . A-3003 Gablitz, Austria Metastatic Skull Tumours Metastatic Skull Tumours: Diagnosis and Management Koichi Mitsuya, Yoko Nakasu Abstract: Metastases of the skull are classifi ed Magnetic resonance imaging is the primary diag- skull metastasis. Surgery is indicated in selected into 2 anatomical groups, presenting distinct clin- nostic tool. Skull metastasis is a focal lesion with patients with good performance status who need ical features. One is calvarial metastasis, which a low-intensity signal on T1-weighted images. En- immediate decompression, cosmetic recovery, or is usually asymptomatic but may cause dural in- hanced T1-weighted images with fat-suppression histological diagnosis. Eur Assoc NeuroOncol vasion, dural sinus occlusion, or cosmetic prob- show tumour, dural infi ltration, and cranial nerve Mag 2014; 4 (2): 71–4. lems. The other is skull-base metastasis, which involvements. Irradiation is the effective and fi rst- presents with cranial-nerve involvement leading line therapy for most skull metastases. Chemo- to devastating symptoms. A high index of suspi- therapy or hormonal therapy is applied depending cion based on new-onset cranial nerve defi cits on tumour sensitivity. -

MBB: Head & Neck Anatomy

MBB: Head & Neck Anatomy Skull Osteology • This is a comprehensive guide of all the skull features you must know by the practical exam. • Many of these structures will be presented multiple times during upcoming labs. • This PowerPoint Handout is the resource you will use during lab when you have access to skulls. Mind, Brain & Behavior 2021 Osteology of the Skull Slide Title Slide Number Slide Title Slide Number Ethmoid Slide 3 Paranasal Sinuses Slide 19 Vomer, Nasal Bone, and Inferior Turbinate (Concha) Slide4 Paranasal Sinus Imaging Slide 20 Lacrimal and Palatine Bones Slide 5 Paranasal Sinus Imaging (Sagittal Section) Slide 21 Zygomatic Bone Slide 6 Skull Sutures Slide 22 Frontal Bone Slide 7 Foramen RevieW Slide 23 Mandible Slide 8 Skull Subdivisions Slide 24 Maxilla Slide 9 Sphenoid Bone Slide 10 Skull Subdivisions: Viscerocranium Slide 25 Temporal Bone Slide 11 Skull Subdivisions: Neurocranium Slide 26 Temporal Bone (Continued) Slide 12 Cranial Base: Cranial Fossae Slide 27 Temporal Bone (Middle Ear Cavity and Facial Canal) Slide 13 Skull Development: Intramembranous vs Endochondral Slide 28 Occipital Bone Slide 14 Ossification Structures/Spaces Formed by More Than One Bone Slide 15 Intramembranous Ossification: Fontanelles Slide 29 Structures/Apertures Formed by More Than One Bone Slide 16 Intramembranous Ossification: Craniosynostosis Slide 30 Nasal Septum Slide 17 Endochondral Ossification Slide 31 Infratemporal Fossa & Pterygopalatine Fossa Slide 18 Achondroplasia and Skull Growth Slide 32 Ethmoid • Cribriform plate/foramina -

Osteoma of Occipital Bone

© 2003 Indian Journal of Surgery www.indianjsurg.comCase Report Effective treatment is crucial for avoiding recurrent Low-grade chondrosarcoma in an extremity can be incidence and depends on excising all tissues with treated with limited surgery. carcinoma. As the tumour is radio-resistant, complete removal is the only treatment of choice. A wide excision REFERENCES for low-grade chondrosarcoma is generally advised. Following open biopsy, local excision or, if required, 1. Bovee JVMG, van der Heul RO, Taminiau AHM, Hogendoorn PCW, reconstruction is advised.5 Chondrosarcoma of the phalanx: A locally aggressive lesion with minimal metastatic potential. Cancer 1999;86:1724-32. 2. Evans HL, Ayala AG, Romsdahl MM, Prognostic factors in chond- In our case, we think that the removal of the tumoral rosarcoma of bone. Cancer 1977;40:818-31. tissue from the normal tissue margin is the treatment 3. Dahlin DC, Beabout JW, Dedifferentiation of low-grade chondro- sarcomas. Cancer 1971;28:461-6. of choice. Our case is a young case that had Grade 1 4. Damron TA, Rock MG, Unni KK, Subcutaneous involvement after chondrosarcoma in his fourth and fifth finger and fifth a metacarpal chondrosarcoma: Case report and review of litera- metatarsal diaphysis. The difference of our case from ture. Clin Orthop 1995;316:189-94. 5. Ogose A, Unni KK, Swee RG, May GK, Rowland CM, Sim FH. the ones reported in literature is that he was young Chondrosarcoma of small bones of the hands and feet. Cancer (18-year-old) and had a lesion involving two different 1997;80:50-9. compartments synchronously as localization. -

WIB Identify Ancestry from Skull

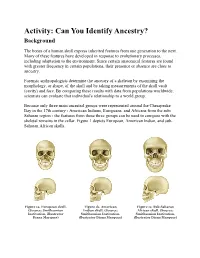

Activity: Can You Identify Ancestry? Background The bones of a human skull express inherited features from one generation to the next. Many of these features have developed in response to evolutionary processes, including adaptation to the environment. Since certain anatomical features are found with greater frequency in certain populations, their presence or absence are clues to ancestry. Forensic anthropologists determine the ancestry of a skeleton by examining the morphology, or shape, of the skull and by taking measurements of the skull vault (cavity) and face. By comparing these results with data from populations worldwide, scientists can evaluate that individual's relationship to a world group. Because only three main ancestral groups were represented around the Chesapeake Bay in the 17th century - American Indians, Europeans, and Africans from the sub- Saharan region - the features from these three groups can be used to compare with the skeletal remains in the cellar. Figure 1 depicts European, American Indian, and sub- Saharan African skulls. Figure 1a. European skull. Figure 1b. American Figure 1c. Sub-Saharan (Source: Smithsonian Indian skull. (Source: African skull. (Source: Institution, illustrator Smithsonian Institution, Smithsonian Institution, Diana Marques) illustrator Diana Marques) illustrator Diana Marques) European Characteristics Figure 2 depicts the characteristics of a European skull. Individuals with European ancestry tend to have straight facial profiles and narrower faces with projecting, sharply angled nasal bones, and these features: Long and narrow face Narrow, high nasal opening Sloping eye orbits Sharp inferior nasal border Larger nasal spine Figure 2. European skull characteristics. (Source: Smithsonian Institution, illustrated by Diana Marques) American Indian Characteristics Figure 3 depicts the characteristics of an American Indian skull. -

Level I to III Craniofacial Approaches Based on Barrow Classification For

Neurosurg Focus 30 (5):E5, 2011 Level I to III craniofacial approaches based on Barrow classification for treatment of skull base meningiomas: surgical technique, microsurgical anatomy, and case illustrations EMEL AVCı, M.D.,1 ERINÇ AKTÜRE, M.D.,1 HAKAN SEÇKIN, M.D., PH.D.,1 KUTLUAY ULUÇ, M.D.,1 ANDREW M. BAUER, M.D.,1 YUSUF IZCI, M.D.,1 JACQUes J. MORCOS, M.D.,2 AND MUSTAFA K. BAşKAYA, M.D.1 1Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Wisconsin; and 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Miami, Florida Object. Although craniofacial approaches to the midline skull base have been defined and surgical results have been published, clear descriptions of these complex approaches in a step-wise manner are lacking. The objective of this study is to demonstrate the surgical technique of craniofacial approaches based on Barrow classification (Levels I–III) and to study the microsurgical anatomy pertinent to these complex craniofacial approaches. Methods. Ten adult cadaveric heads perfused with colored silicone and 24 dry human skulls were used to study the microsurgical anatomy and to demonstrate craniofacial approaches in a step-wise manner. In addition to cadaveric studies, case illustrations of anterior skull base meningiomas were presented to demonstrate the clinical application of the first 3 (Levels I–III) approaches. Results. Cadaveric head dissection was performed in 10 heads using craniofacial approaches. Ethmoid and sphe- noid sinuses, cribriform plate, orbit, planum sphenoidale, clivus, sellar, and parasellar regions were shown at Levels I, II, and III. In 24 human dry skulls (48 sides), a supraorbital notch (85.4%) was observed more frequently than the supraorbital foramen (14.6%). -

Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Lung with Skull Metastasis: a Case Report

y & R ar esp on ir m a l to u r y Mandal et al. J Pulm Respir Med 2015, 5:5 P f M o e l Journal of Pulmonary & Respiratory d a i DOI: 10.4172/2161-105X.1000292 n c r i n u e o J ISSN: 2161-105X Medicine Case Report Open Access Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Lung with Skull Metastasis: A Case Report Sanchayan Mandal*, Devleena, Tamohan Chaudhuri and Subhra Sil Department of Radiotherapy, Saroj Gupta Cancer Centre and Research Institute (Sgccri), Kolkata, India Abstract Background: Squamous cell carcinoma lung presents about 30 percent of all non small cell lung carcinoma. It almost always associated with smoking and usually spreads to brain, bones, liver, adrenal glands and small intestine. But, spreading to skull bones is a rare event. Case Presentation: We here present a case of a 43 year old smoker with squamous cell carcinoma of lung where patient admitted with huge skull lesion invading through both inner and outer table and brain also. Previously, patient underwent lobectomy and three cycles of chemotherapy. This time, patient received palliative radiation to skull at our institute. Conclusion: There is only single case report worldwide similar to this case and proved the unusual presentation of this rare occurrence. It also raises questions about the appropriate management of patients with intracranial metastasis with invasion of skull. Keywords: Squamous cell carcinoma; Skull mets; Carcinoma soft tissue component infiltrating the adjacent fronto parietal cerebral lung; Post lobectomy neuroparenchyma with significant perilesional edema and mass effect. Immunohistochemistry of lung lesion showed membranous positivity Introduction of CK 5/6 (Figure 4) and nuclear positivity of P63 (Figure 5). -

Occipital Bone Osteoma

Sinir Sistemi Cerrahisi Derg 4(3):134-137, 2014 doi:10.5222/sscd.2014.134 Olgu Sunumu Occipital Bone Osteoma Nilgün Şenol1, Fatma Nilgün KapucuoĞlu2, Yavuz Selim AYdıN1 1Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Tip Fakültesi, Beyin ve Sinir Cerrahisi Anabilim Dalı, Isparta 2Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Tip Fakültesi, Patoloji Anabilim Dalı, Isparta Osteomas are benign bone-forming tumours. They are mostly seen in the frontoethmoidal region in the head and neck region, and occipital localization is extremely rare. They are often asymptomat- hic lesions, and can be detected by cosmetic complaint of the patient. In large tumours headache and dizziness can be the symptoms. A 39-year-old female admitted for gradual enlargement of a swelling on the left side of the back of her head, and nonspecific headache. In physical examina- tion a bony hard, immobile, non-tender lesion on left occipital bone was detected. Neurological examination was normal. In brain computed tomography, a bony mass of 3.5 cm in diameter and 1 cm thick was revealed. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a well-circumscribed hypointense lesion with dimensions of 3x3,5x1 cm which caused a slight compression on the parenchyma of the left occipital region. Lesion was totally excised to relieve cosmotic deformity. Histopathological examination revealed it to be an osteoma. Before surgery differential diagnosis, and extension of the lesion should be carefully explored. We reported this case. Because of rarity of occipital loca- lization. Key words: Occipital bone, osteoma, bone tumour J Nervous Sys Surgery 2014; 4(3):134-137 Oksipital Kemik Osteomu Osteomlar iyi huylu kemikten gelişen tümörlerdir. Baş ve boyun bölgesinde sıklıkla frontoetmoidal alanda görülürler ve oksipital yerleşim oldukça enderdir. -

Connections of the Skull Bones. Temporomandibular Joint

Connections of the skull bones. Temporomandibular joint. Masticatory muscles, mimic muscles and their innervation. Veronika Němcová, CSc. Connections of the skull bones • Synchondroses cranii • Syndesmoses - suturae cranii, gomphosis • Synostoses • Articulatio temporomandibularis Cartilaginous connections Synchondrosis sphenopetrosa (foramen lacerum) Synchondrosis petrooccipitalis (fissura petrooccipitalis) Synchondrosis Fonticulus Synchondrosis sphenooccipitalis intraoccipitalis mastoideus anterior Symphysis menti Synchondrosis intraoccipitalis posterior Cartilaginous and fibrous connection on the newborn skull Sutura coronalis Sutura squamosa Sutura lambdoidea Sutura sagittalis Sutures newborn Articulatio temporomandibularis complex– discus head: caput mandibulae fossa: fossa mandibularis, tuberculum articulare Articular surfices are covered by fibrous cartilage Movements : depression elevation protraction retraction lateropulsion Ligaments of the temporomandibular joint – lateral aspect Ligamentum laterale - it prevents posterior displacement of the resting condyle Ligamentum stylomandibulare Ligaments of the temporomandibular joint - medial aspect Lig.pterygospinale Lig.sphenomandibulare Lig.stylomandibulare Lig. pterygomandibulare (raphe buccopharyngea) Ligaments of the temporomandibular joint Lig. pterygospinale Lig. stylomandibulare Lig. sphenomandibulare Articulatio temporomandibularis sagittal section (after Frick) Meatus acusticus Discus articularis externus A P Retroarticular plastic pad (Zenker) Caput mandibulae (veins and