Laboratory 1 Worksheet: the Skull Objective: Learn About The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015)

IUCN Red List version 2015.4: Table 7 Last Updated: 19 November 2015 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2014 (IUCN Red List version 2014.3) and 2015 (IUCN Red List version 2015-4) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered, EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2014) List (2015) change version Category Category MAMMALS Aonyx capensis African Clawless Otter LC NT N 2015-2 Ailurus fulgens Red Panda VU EN N 2015-4 -

JVP 26(3) September 2006—ABSTRACTS

Neoceti Symposium, Saturday 8:45 acid-prepared osteolepiforms Medoevia and Gogonasus has offered strong support for BODY SIZE AND CRYPTIC TROPHIC SEPARATION OF GENERALIZED Jarvik’s interpretation, but Eusthenopteron itself has not been reexamined in detail. PIERCE-FEEDING CETACEANS: THE ROLE OF FEEDING DIVERSITY DUR- Uncertainty has persisted about the relationship between the large endoskeletal “fenestra ING THE RISE OF THE NEOCETI endochoanalis” and the apparently much smaller choana, and about the occlusion of upper ADAM, Peter, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; JETT, Kristin, Univ. of and lower jaw fangs relative to the choana. California, Davis, Davis, CA; OLSON, Joshua, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los A CT scan investigation of a large skull of Eusthenopteron, carried out in collaboration Angeles, CA with University of Texas and Parc de Miguasha, offers an opportunity to image and digital- Marine mammals with homodont dentition and relatively little specialization of the feeding ly “dissect” a complete three-dimensional snout region. We find that a choana is indeed apparatus are often categorized as generalist eaters of squid and fish. However, analyses of present, somewhat narrower but otherwise similar to that described by Jarvik. It does not many modern ecosystems reveal the importance of body size in determining trophic parti- receive the anterior coronoid fang, which bites mesial to the edge of the dermopalatine and tioning and diversity among predators. We established relationships between body sizes of is received by a pit in that bone. The fenestra endochoanalis is partly floored by the vomer extant cetaceans and their prey in order to infer prey size and potential trophic separation of and the dermopalatine, restricting the choana to the lateral part of the fenestra. -

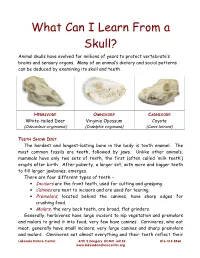

What Can I Learn from a Skull? Animal Skulls Have Evolved for Millions of Years to Protect Vertebrate’S Brains and Sensory Organs

What Can I Learn From a Skull? Animal skulls have evolved for millions of years to protect vertebrate’s brains and sensory organs. Many of an animal’s dietary and social patterns can be deduced by examining its skull and teeth. HERBIVORE OMNIVORE CARNIVORE White-tailed Deer Virginia Opossum Coyote (Odocoileus virginianus) (Didelphis virginiana) (Canis latrans) TEETH SHOW DIET . The hardest and longest-lasting bone in the body is tooth enamel. The most common fossils are teeth, followed by jaws. Unlike other animals, mammals have only two sets of teeth, the first (often called ‘milk teeth’) erupts after birth. After puberty, a larger set, with more and bigger teeth to fill larger jawbones, emerges. There are four different types of teeth – • Incisors are the front teeth, used for cutting and grasping. • Canines are next to incisors and are used for tearing. • Premolars , located behind the canines, have sharp edges for crushing food. • Molars , the very back teeth, are broad, flat grinders. Generally, herbivores have large incisors to nip vegetation and premolars and molars to grind it into food; very few have canines. Carnivores, who eat meat, generally have small incisors, very large canines and sharp premolars and molars. Omnivores eat almost everything and their teeth reflect their Lakeside Nature Center 4701 E Gregory, KCMO 64132 816-513-8960 www.lakesidenaturecenter.org preferences; they have all four types of teeth. In fact, if you’d like to see an excellent example of an omnivore’s teeth, look in the mirror. EYE PLACEMENT IDENTIFIES PREDATORS . Carnivores generally have large eyes, placed so that the eyes look forward and the areas of vision of the two eyes overlap. -

Dental and Temporomandibular Joint Pathology of the Kit Fox (Vulpes Macrotis)

Author's Personal Copy J. Comp. Path. 2019, Vol. 167, 60e72 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect www.elsevier.com/locate/jcpa DISEASE IN WILDLIFE OR EXOTIC SPECIES Dental and Temporomandibular Joint Pathology of the Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis) N. Yanagisawa*, R. E. Wilson*, P. H. Kass† and F. J. M. Verstraete* *Department of Surgical and Radiological Sciences and † Department of Population Health and Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, California, USA Summary Skull specimens from 836 kit foxes (Vulpes macrotis) were examined macroscopically according to predefined criteria; 559 specimens were included in this study. The study group consisted of 248 (44.4%) females, 267 (47.8%) males and 44 (7.9%) specimens of unknown sex; 128 (22.9%) skulls were from young adults and 431 (77.1%) were from adults. Of the 23,478 possible teeth, 21,883 teeth (93.2%) were present for examina- tion, 45 (1.9%) were absent congenitally, 405 (1.7%) were acquired losses and 1,145 (4.9%) were missing ar- tefactually. No persistent deciduous teeth were observed. Eight (0.04%) supernumerary teeth were found in seven (1.3%) specimens and 13 (0.06%) teeth from 12 (2.1%) specimens were malformed. Root number vari- ation was present in 20.3% (403/1,984) of the present maxillary and mandibular first premolar teeth. Eleven (2.0%) foxes had lesions consistent with enamel hypoplasia and 77 (13.8%) had fenestrations in the maxillary alveolar bone. Periodontitis and attrition/abrasion affected the majority of foxes (71.6% and 90.5%, respec- tively). -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

LIS T OF ILL US TRA TIONS. IX Pa«e. Apices of ovipositors : o, Polysphincta texaiui Cresson ; &, Eymenoepi- meois iciltii (Cresson); Mandible; c, H. tmltii (Cresson) 389 Apex of ovipositor of Theronia fulvesceiis Cresson 389 Apices of ovipositors: a, Itoplectis canqMisitor Say; b, Apechthis pictir cornis (Cresson) 389 Apex of abdomen of female of Coleocentrus occidentalis 390 Areolet of Lahena grallatoi- (Say) 390 Areolets: a, Tromatohia rufovariata (Cresson) ; b, Itoplectis conquisitor (Say) ; c, Epiurus alboricta (Cresson) 390 Sessile first tergite of Perithous pleuralis (Cresson) 390 Petioatel first tergite of Xorides yukonensis (Rohwer) 390 Mandible of Poemenva americana (Cresson) 391 Female of Labena confusa Rohwer 412 Female of Rhyssella nitida (Cresson) 424 Propodeum of Zonde* picea*u« (Rohwer) 434 Front view of head of Xoi'ides albopictus (Cresson) 437 Propodeum and basal abdominal segments of Xorides albopictus (Cresson) 437 Apical abdomen segments of Xorides albopictus (Cresson) 437 Female of Xorides rileyi (Ashmead) 440 Front view of head of Deuteroxorides caryae (Harrington) 446 Propodeum and basal abdominal segments of Deuteroxorides caryae (Harrington) 446 Apical abdominal segments of Z)c«feroa:ori<Ze« caryae (Harrington) 446 Female of Deuteroxorides caryae (Harrington) 447 Female of Odontomerus canadensis Provancher 459 Female of Phytodietus annulatus (Provancher) 467 Femaie of Phydotietus annulatus (Provancher) 467 Diagram showing relation of dike to vein, Hecla Mine. A, Dike; B, Crushed material with quartz and ore; C, Galena; D, Quartzite wall rock ; width of section 15 feet 481 Showing relation to dikes (A) to vein (B) on No. 1 level of Marsh Mine_ 484 Showing relation of dike (A) to vein (B) on 2,000-foot level of Standard- Mammoth Mine 492 Showing relation of dike (A) to vein (B) on 1,200-foot level of Standard- Mammoth Mine 492 Coleocentrus occidentalis. -

PE2812 Breaking Arm Bones a Second Time

Breaking Arm Bones a Second Time Children who have broken arm bones are at higher risk for breaking the same arm bones again if they do not go through the right treatment, for the right amount of time. How likely is it that There is up to a 5% chance (1 out of every 20 cases) of breaking forearm my child’s arm bones a second time, in the same place. There is a higher risk to break these bones again if the first fracture is in the middle of the forearm bones (as bones will break seen in the pictures below). There is a lower risk if the fracture is closer to again? the hand. Most repeat fractures tend to happen within six months after the first injury heals. First fracture Same fracture after healing for about 6 weeks 1 of 2 To Learn More Free Interpreter Services • Orthopedics and Sports Medicine • In the hospital, ask your nurse. 206-987-2109 • From outside the hospital, call the • Ask your child’s healthcare provider toll-free Family Interpreting Line, 1-866-583-1527. Tell the interpreter • seattlechildrens.org the name or extension you need. Breaking Arm Bones a Second Time How can I help my Wearing a cast for at least six weeks lowers the risk of breaking the same child lower the risk arm bones again. After wearing a cast, we recommend your child wear a brace for 4 weeks in order to protect the injured area and start improving of having a wrist movement. While your child wears a brace, we recommend they do repeated bone not participate in contact sports (e.g., soccer, football or dodge ball). -

The Cat Mandible (II): Manipulation of the Jaw, with a New Prosthesis Proposal, to Avoid Iatrogenic Complications

animals Review The Cat Mandible (II): Manipulation of the Jaw, with a New Prosthesis Proposal, to Avoid Iatrogenic Complications Matilde Lombardero 1,*,† , Mario López-Lombardero 2,†, Diana Alonso-Peñarando 3,4 and María del Mar Yllera 1 1 Unit of Veterinary Anatomy and Embryology, Department of Anatomy, Animal Production and Clinical Veterinary Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Campus of Lugo—University of Santiago de Compostela, 27002 Lugo, Spain; [email protected] 2 Engineering Polytechnic School of Gijón, University of Oviedo, 33203 Gijón, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Animal Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Campus of Lugo—University of Santiago de Compostela, 27002 Lugo, Spain; [email protected] 4 Veterinary Clinic Villaluenga, calle Centro n◦ 2, Villaluenga de la Sagra, 45520 Toledo, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-982-822-333 † Both authors contributed equally to this manuscript. Simple Summary: The small size of the feline mandible makes its manipulation difficult when fixing dislocations of the temporomandibular joint or mandibular fractures. In both cases, non-invasive techniques should be considered first. When not possible, fracture repair with internal fixation using bone plates would be the best option. Simple jaw fractures should be repaired first, and caudal to rostral. In addition, a ventral approach makes the bone fragments exposure and its manipulation easier. However, the cat mandible has little space to safely place the bone plate screws without damaging the tooth roots and/or the mandibular blood and nervous supply. As a consequence, we propose a conceptual model of a mandibular prosthesis that would provide biomechanical Citation: Lombardero, M.; stabilization, avoiding any unintended (iatrogenic) damage to those structures. -

An Educator's Resource to Texas Mammal Skulls and Skins

E4H-014 11/17 An Educator’s Resource to Texas Mammal Skulls and Skins for use in 4-H Wildlife Programs and FFA Wildlife Career Development Events By, Denise Harmel-Garza Program Coordinator I, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service, 4-H Photographer and coauthor, Audrey Sepulveda M.Ed. Agricultural Leadership, Education and Communications, Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 2017 “A special thanks to the Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collections at Texas A&M University for providing access to their specimens.” Texas A&M AgriLife Extension provides equal opportunities in its programs and employment to all persons, regardless of race, color, sex, religion, national origin, disability, age, genetic information, veteran status, sexual orientation, or gender identity. The Texas A&M University System, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the County Commissioners Courts of Texas Cooperating. Introduction Texas youth that participate in wildlife programs may be asked to identify a skull, skin, scat, tracks, etc. of an animal. Usually, educators must find this information and assemble pictures of skulls and skins from various sources. They also must ensure that what they find is relevant and accurate. Buying skulls and skins to represent all Texas mammals is costly. Most educators cannot afford them, and if they can, maintaining these collections over time is problematic. This study resource will reduce the time teachers across the state need to spend searching for information and allow them more time for presenting the material to their students. This identification guide gives teachers and students easy access to information that is accurate and valuable for learning to identify Texas mammals. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Perinate and Eggs of a Giant Caenagnathid Dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Central China

ARTICLE Received 29 Jul 2016 | Accepted 15 Feb 2017 | Published 9 May 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms14952 OPEN Perinate and eggs of a giant caenagnathid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of central China Hanyong Pu1, Darla K. Zelenitsky2, Junchang Lu¨3, Philip J. Currie4, Kenneth Carpenter5,LiXu1, Eva B. Koppelhus4, Songhai Jia1, Le Xiao1, Huali Chuang1, Tianran Li1, Martin Kundra´t6 & Caizhi Shen3 The abundance of dinosaur eggs in Upper Cretaceous strata of Henan Province, China led to the collection and export of countless such fossils. One of these specimens, recently repatriated to China, is a partial clutch of large dinosaur eggs (Macroelongatoolithus) with a closely associated small theropod skeleton. Here we identify the specimen as an embryo and eggs of a new, large caenagnathid oviraptorosaur, Beibeilong sinensis. This specimen is the first known association between skeletal remains and eggs of caenagnathids. Caenagnathids and oviraptorids share similarities in their eggs and clutches, although the eggs of Beibeilong are significantly larger than those of oviraptorids and indicate an adult body size comparable to a gigantic caenagnathid. An abundance of Macroelongatoolithus eggs reported from Asia and North America contrasts with the dearth of giant caenagnathid skeletal remains. Regardless, the large caenagnathid-Macroelongatoolithus association revealed here suggests these dinosaurs were relatively common during the early Late Cretaceous. 1 Henan Geological Museum, Zhengzhou 450016, China. 2 Department of Geoscience, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 1N4. 3 Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100037, China. 4 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E9. 5 Prehistoric Museum, Utah State University, 155 East Main Street, Price, Utah 84501, USA. -

A New Caenagnathid Dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Wangshi

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A new caenagnathid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Wangshi Group of Shandong, China, with Received: 12 October 2017 Accepted: 7 March 2018 comments on size variation among Published: xx xx xxxx oviraptorosaurs Yilun Yu1, Kebai Wang2, Shuqing Chen2, Corwin Sullivan3,4, Shuo Wang 5,6, Peiye Wang2 & Xing Xu7 The bone-beds of the Upper Cretaceous Wangshi Group in Zhucheng, Shandong, China are rich in fossil remains of the gigantic hadrosaurid Shantungosaurus. Here we report a new oviraptorosaur, Anomalipes zhaoi gen. et sp. nov., based on a recently collected specimen comprising a partial left hindlimb from the Kugou Locality in Zhucheng. This specimen’s systematic position was assessed by three numerical cladistic analyses based on recently published theropod phylogenetic datasets, with the inclusion of several new characters. Anomalipes zhaoi difers from other known caenagnathids in having a unique combination of features: femoral head anteroposteriorly narrow and with signifcant posterior orientation; accessory trochanter low and confuent with lesser trochanter; lateral ridge present on femoral lateral surface; weak fourth trochanter present; metatarsal III with triangular proximal articular surface, prominent anterior fange near proximal end, highly asymmetrical hemicondyles, and longitudinal groove on distal articular surface; and ungual of pedal digit II with lateral collateral groove deeper and more dorsally located than medial groove. The holotype of Anomalipes zhaoi is smaller than is typical for Caenagnathidae but larger than is typical for the other major oviraptorosaurian subclade, Oviraptoridae. Size comparisons among oviraptorisaurians show that the Caenagnathidae vary much more widely in size than the Oviraptoridae. Oviraptorosauria is a clade of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs characterized by a short, high skull, long neck and short tail. -

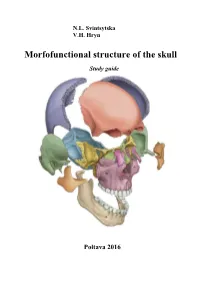

Morfofunctional Structure of the Skull

N.L. Svintsytska V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine Public Institution «Central Methodological Office for Higher Medical Education of MPH of Ukraine» Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukranian Medical Stomatological Academy» N.L. Svintsytska, V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 2 LBC 28.706 UDC 611.714/716 S 24 «Recommended by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine as textbook for English- speaking students of higher educational institutions of the MPH of Ukraine» (minutes of the meeting of the Commission for the organization of training and methodical literature for the persons enrolled in higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of postgraduate education MPH of Ukraine, from 02.06.2016 №2). Letter of the MPH of Ukraine of 11.07.2016 № 08.01-30/17321 Composed by: N.L. Svintsytska, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor V.H. Hryn, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor This textbook is intended for undergraduate, postgraduate students and continuing education of health care professionals in a variety of clinical disciplines (medicine, pediatrics, dentistry) as it includes the basic concepts of human anatomy of the skull in adults and newborns. Rewiewed by: O.M. Slobodian, Head of the Department of Anatomy, Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Bukovinian State Medical University», Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M.V.