Aphanius Fasciatus) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deterministic Shifts in Molecular Evolution Correlate with Convergence to Annualism in Killifishes

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.09.455723; this version posted August 10, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Deterministic shifts in molecular evolution correlate with convergence to annualism in killifishes Andrew W. Thompson1,2, Amanda C. Black3, Yu Huang4,5,6 Qiong Shi4,5 Andrew I. Furness7, Ingo, Braasch1,2, Federico G. Hoffmann3, and Guillermo Ortí6 1Department of Integrative Biology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48823, USA. 2Ecology, Evolution & Behavior Program, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA. 3Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Entomology, & Plant Pathology, Mississippi State University, Starkville, MS 39759, USA. 4Shenzhen Key Lab of Marine Genomics, Guangdong Provincial Key Lab of Molecular Breeding in Marine Economic Animals, BGI Marine, Shenzhen 518083, China. 5BGI Education Center, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenzhen 518083, China. 6Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052, USA. 7Department of Biological and Marine Sciences, University of Hull, UK. Corresponding author: Andrew W. Thompson, [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.09.455723; this version posted August 10, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract: The repeated evolution of novel life histories correlating with ecological variables offer opportunities to test scenarios of convergence and determinism in genetic, developmental, and metabolic features. Here we leverage the diversity of aplocheiloid killifishes, a clade of teleost fishes that contains over 750 species on three continents. -

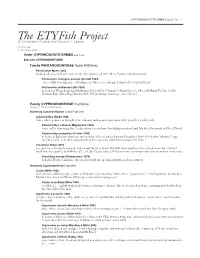

The Etyfish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J

CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3) · 1 The ETYFish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara COMMENTS: v. 3.0 - 13 Nov. 2020 Order CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3 of 4) Suborder CYPRINODONTOIDEI Family PANTANODONTIDAE Spine Killifishes Pantanodon Myers 1955 pan(tos), all; ano-, without; odon, tooth, referring to lack of teeth in P. podoxys (=stuhlmanni) Pantanodon madagascariensis (Arnoult 1963) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Madagascar, where it is endemic [extinct due to habitat loss] Pantanodon stuhlmanni (Ahl 1924) in honor of Franz Ludwig Stuhlmann (1863-1928), German Colonial Service, who, with Emin Pascha, led the German East Africa Expedition (1889-1892), during which type was collected Family CYPRINODONTIDAE Pupfishes 10 genera · 112 species/subspecies Subfamily Cubanichthyinae Island Pupfishes Cubanichthys Hubbs 1926 Cuba, where genus was thought to be endemic until generic placement of C. pengelleyi; ichthys, fish Cubanichthys cubensis (Eigenmann 1903) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Cuba, where it is endemic (including mainland and Isla de la Juventud, or Isle of Pines) Cubanichthys pengelleyi (Fowler 1939) in honor of Jamaican physician and medical officer Charles Edward Pengelley (1888-1966), who “obtained” type specimens and “sent interesting details of his experience with them as aquarium fishes” Yssolebias Huber 2012 yssos, javelin, referring to elongate and narrow dorsal and anal fins with sharp borders; lebias, Greek name for a kind of small fish, first applied to killifishes (“Les Lebias”) by Cuvier (1816) and now a -

From the Western Mosquitofish, Gambusia Affinis (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae): New Distributional Records for Arkansas, Kansas and Oklahoma

42 Salsuginus seculus (Monogenoidea: Dactylogyrida: Ancyrocephalidae) from the Western Mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae): New distributional records for Arkansas, Kansas and Oklahoma Chris T. McAllister Science and Mathematics Division, Eastern Oklahoma State College, Idabel, OK 74745 Donald G. Cloutman P. O. Box 197, Burdett, KS 67523 Henry W. Robison Department of Biology, Southern Arkansas University, Magnolia, AR 71754 Studies on fish monogeneans in Oklahoma and S. fundulus (Mizelle) Murith and Beverley- are relatively uncommon (Seamster 1937, 1938, Burton in Northern Studfish,Fundulus catenatus 1960; Mizelle 1938; Monaco and Mizelle 1955; (McAllister et al. 2015, 2016). In Kansas, a McDaniel 1963; McDaniel and Bailey 1966; single species, S. thalkeni Janovy, Ruhnke, and Wheeler and Beverley-Burton 1989) with little Wheeler (syn. S. fundulus) has been reported or no published work in the past two decades from Northern Plains Killifish,Fundulus kansae or more. Members of the ancyrocephalid (see Janovy et al. 1989). Here, we report genus Salsuginus (Beverley-Burton) Murith new distributional records for a species of and Beverley-Burton have been reported Salsuginus in Arkansas, Kansas and Oklahoma. from various fundulid fishes including those from Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, During June 1983 (Kansas only) and again Nebraska, New York, Tennessee, and Texas, between April 2014 and September 2015, and Newfoundland and Ontario, Canada, 36 Western Mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis and the Bahama Islands; additionally, two were collected by dipnet, seine (3.7 m, 1.6 species have been reported from the Western mm mesh) or backpack electrofisher from Big Mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis (Poeciliidae) Spring at Spring Mill, Independence County, from California, Louisiana, and Texas, and Arkansas (n = 4; 35.828152°N, 91.724273°W), the Bahama Islands (see Hoffman 1999). -

The Mystery of the Banded Killifish Fundulus Diaphanus Population Explosion: Where Did They All Come From?

The Mystery of the Banded KillifishFundulus ( diaphanus) Population Explosion: Where Did They All Come from? Philip W. Willink, Jeremy S. Tiemann, Joshua L. Sherwood, Eric R. Larson, Abe Otten, Brian Zimmerman 3 American Currents Vol. 44, No. 4 THE MYSTERY OF THE BANDED KILLIFISH FUNDULUS DIAPHANUS POPULATION EXPLOSION: WHERE DID THEY ALL COME FROM? Philip W. Willink, Jeremy S. Tiemann, Joshua L. Sherwood, La Grange Park, IL Illinois Natural History Survey Illinois Natural History Survey Eric R. Larson, Abe Otten, Brian Zimmerman University of Illinois at Scott Community The Ohio State University Urbana-Champaign College Stream and River Ecology Lab Banded Killifish Fundulus diaphanus are no strangers to NAN- and have not been seen since, they were only known from a hand- FAers. Over the past several years, there have been multiple arti- ful of inland lakes in the far northeastern corner the state (Fig. 1). cles in American Currents covering their distribution (Hatch 2015; Even there, population numbers were low. Schmidt 2016a, 2018; Olson and Schmidt 2018; Li 2019), stocking So it was with great excitement that in the early 2000s Illinois to restore populations (Bland 2013; Schmidt 2014), and appear- ichthyologists started to find more and more presumed Western ance in a hatchery (Schmidt 2016b). Their range extends from the Banded Killifish in Lake Michigan (Willink et al. 2018). They Canadian Maritime provinces south along the Atlantic coast to were even showing up in downtown Chicago (Willink 2011). It the Carolinas, as well as westward through the Great Lakes region was hoped that this range expansion was evidence of an uncom- to the upper Mississippi watershed. -

Gene Expression After Freshwater Transfer in Gills and Opercular Epithelia of Killifish: Insight Into Divergent Mechanisms of Ion Transport Graham R

The Journal of Experimental Biology 208, 2719-2729 2719 Published by The Company of Biologists 2005 doi:10.1242/jeb.01688 Gene expression after freshwater transfer in gills and opercular epithelia of killifish: insight into divergent mechanisms of ion transport Graham R. Scott1,*, James B. Claiborne2, Susan L. Edwards2,3, Patricia M. Schulte1 and Chris M. Wood4 1Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver BC, Canada V6T 1Z4, 2Department of Biology, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA 30460-8042, USA, 3Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD 4879, Australia and 4Department of Biology, McMaster University, Hamilton ON, Canada L8S 4K1 *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 17 May 2005 Summary We have explored the molecular basis for differences in epithelium, NHE2 was not expressed; furthermore, physiological function between the gills and opercular Na+,K+-ATPase activity was unchanged after transfer to epithelium of the euryhaline killifish Fundulus freshwater, CA2 mRNA levels decreased, and NHE3 levels heteroclitus. These tissues are functionally similar in increased. Consistent with their functional similarities in seawater, but in freshwater the gills actively absorb Na+ seawater, killifish gills and opercular epithelium expressed – + + + + – but not Cl , whereas the opercular epithelium actively Na ,K -ATPase α1a, Na ,K ,2Cl cotransporter 1 absorbs Cl– but not Na+. These differences in freshwater (NKCC1), cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance physiology are likely due to differences in absolute levels regulator (CFTR) Cl– channel and the signalling protein of gene expression (measured using real-time PCR), as 14-3-3a at similar absolute levels. Furthermore, NKCC1 several proteins important for Na+ transport, namely and CFTR were suppressed equally in each tissue after Na+,H+-exchanger 2 (NHE2), carbonic anhydrase 2 (CA2), freshwater transfer, and 14-3-3a mRNA increased in both. -

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019)

IUCN Red List version 2019-3: Table 7 Last Updated: 10 December 2019 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2018 (IUCN Red List version 2018-2) and 2019 (IUCN Red List version 2019-3) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered [CR(PE) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct), CR(PEW) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct in the Wild)], EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2018) List (2019) change version Category -

The African Turquoise Killifish: a Model for Exploring Vertebrate Aging and Diseases in the Fast Lane

Downloaded from symposium.cshlp.org on June 11, 2016 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press The African Turquoise Killifish: A Model for Exploring Vertebrate Aging and Diseases in the Fast Lane 1 1,2 ITAMAR HAREL AND ANNE BRUNET 1Department of Genetics, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305 2Glenn Laboratories for the Biology of Aging at Stanford, Stanford, California 94305 Correspondence: [email protected] Why and how organisms age remains a mystery, and it defines one of the biggest challenges in biology. Aging is also the primary risk factor for many human pathologies, such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases. Thus, manipulating the aging rate and potentially postponing the onset of these devastating diseases could have a tremendous impact on human health. Recent studies, relying primarily on nonvertebrate short-lived model systems, have shown the importance of both genetic and environmental factors in modulating the aging rate. However, relatively little is known about aging in vertebrates or what processes may be unique and specific to these complex organisms. Here we discuss how advances in genomics and genome editing have significantly expanded our ability to probe the aging process in a vertebrate system. We highlight recent findings from a naturally short-lived vertebrate, the African turquoise killifish, which provides an attractive platform for exploring mechanisms underlying vertebrate aging and age-related diseases. MODELING AGING IN THE ing vertebrate aging and age-related diseases (Harel et al. LABORATORY 2015). Aging research has greatly benefited from investigating short-lived nonvertebrate models (Fig. 1A), specifically THE AFRICAN TURQUOISE KILLIFISH yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), worm (Caenorhabdi- tis elegans), and fly (Drosophila melanogaster). -

Draft Risk Assessment Report Nothobranchius Furzeri (Turquoise

APPLICATION TO AMEND THE LIST OF SPECIMENS SUITABLE FOR LIVE IMPORT Draft Risk Assessment Report 1. Taxonomy of the species a. Family name: Aplocheilidae b. Genus name: Nothobranchius c. Species: N. furzeri d. Subspecies: No e. Taxonomic Reference: http://www.uniprot.org/taxonomy/105023 f. Common Names: Turquoise killifish g. Is the species a genetically-modified organism (GMO)? No 2. Status of the species under CITES Species is not listed in the CITES Appendices. 3. Ecology of the species a. Longevity: what is the average lifespan of the species in the wild and in captivity? The average lifespan of the species in captivity is 13 weeks (1). Wild derived N. furzeri from three different habitats showed a maximum lifespan of 25-32 weeks (1). b. What is the maximum length and weight that the species attains? Provide information on the size and weight range for males and females of the species. As per the original formal description of the species, the standard length of N. furzeri from a wild population ranged from 2.5cm to 4.4cm (2). The maximum length the species can attain is 7cm (3). The mean maximal body weight reported for males is 3.8 ± 1.1 g (range: 0.5 – 6.7 g) and 2.2 ± 0.6 g (range: 0.2 - 3.6 g) for females (4). Growth rates of Nothobranchius in the wild have been reported to be similar to those in captivity (5). c. Discuss the identification of the individuals in this species, including if the sexes of the species are readily distinguishable, and if the species is difficult to distinguish from other species. -

Life History Patterns and Biogeography: An

LIFE HISTORY PATTERNS AND Lynne R. Parenti2 BIOGEOGRAPHY: AN INTERPRETATION OF DIADROMY IN FISHES1 ABSTRACT Diadromy, broadly defined here as the regular movement between freshwater and marine habitats at some time during their lives, characterizes numerous fish and invertebrate taxa. Explanations for the evolution of diadromy have focused on ecological requirements of individual taxa, rarely reflecting a comparative, phylogenetic component. When incorporated into phylogenetic studies, center of origin hypotheses have been used to infer dispersal routes. The occurrence and distribution of diadromy throughout fish (aquatic non-tetrapod vertebrate) phylogeny are used here to interpret the evolution of this life history pattern and demonstrate the relationship between life history and ecology in cladistic biogeography. Cladistic biogeography has been mischaracterized as rejecting ecology. On the contrary, cladistic biogeography has been explicit in interpreting ecology or life history patterns within the broader framework of phylogenetic patterns. Today, in inferred ancient life history patterns, such as diadromy, we see remnants of previously broader distribution patterns, such as antitropicality or bipolarity, that spanned both marine and freshwater habitats. Biogeographic regions that span ocean basins and incorporate ocean margins better explain the relationship among diadromy, its evolution, and its distribution than do biogeographic regions centered on continents. Key words: Antitropical distributions, biogeography, diadromy, eels, -

Gill Trematodes (Flukes) in Wild-Caught Killifish (<I>Fundulus

NOTES Gill Trematodes (Flukes) in Wild-Caught Killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus) DAVID R. GOULDING, BS, RLAT,1* TERRY L. BLANKENSHIP-PARIS, DVM, MS, DIPLOMATE, ACLAM,1 GREGORY A. LEWBART, MS, VMD, DIPLOMATE, ACZM,2 PAGE H. MYERS, BS, LATG,1 TRACY K. DEMIANENKO, BS, RLAT,1 JAMES A. CLARK, LATG,1 AND DIANE B. FORSYTHE, DVM, DIPLOMATE, ACLAM1 Three wild caught killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus) on an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol were found dead within 2 days after being received. The fish were housed in two separate aquaria. Aquarium water was evaluated, and pH, salinity, ammonia, nitrate, and nitrite levels were within acceptable parameters. Several remaining fish appeared to be slow-moving and were presented for necropsy. Multiple, scattered, ulcerated skin lesions (diameter, 1 to 5 mm) were noted at necropsy and were cultured. No pathogenic bacteria were isolated. Wet-mount samples of the gills revealed multiple cysts at the gill margins, each containing a motile organism. No other gill parasites were detected. A diagnosis of trematodiasis was made. The cysts were identified as encysted metacercariae of a digenetic trematode. We surmise that the large numbers of gill flukes combined with the stress of recent shipment likely caused the observed morbidity and mortality. Sixty-two wild-caught killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus) obtained from Duke Marine Center (Beaufort, N.C.) were group-housed upon receipt in two 38-gallon aquaria containing conditioned brack- ish water. Thirty-six fish were placed in tank A, and 26 fish were placed in tank B. One day after arrival, two fish were found dead in tank B, and 2 days after arrival, one fish was found dead in tank A. -

Re-Validation and Re-Description of an Endemic and Threatened Species, Aphanius Pluristriatus (Jenkins, 1910) (Teleostei, Cyprinodontidae), from Southern Iran

Zootaxa 3208: 58–67 (2012) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2012 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Re-validation and re-description of an endemic and threatened species, Aphanius pluristriatus (Jenkins, 1910) (Teleostei, Cyprinodontidae), from southern Iran HAMID REZA ESMAEILI1,4, AZAD TEIMORI2,3, ZEINAB GHOLAMI3, NEDA ZAREI1 & BETTINA REICHENBACHER3,4 1Department of Biology, College of Sciences, Shiraz University, Shiraz 71454, Iran. 2Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Shahid-Bahonar University of Kerman 22 Bahman Blvd. Kerman, 76169-14111 Iran 3Department of Earth- and Environmental Sciences, Palaeontology & Geobiology & GeoBio-CenterLMU, Ludwig-Maximilians-Univer- sity, Richard-Wagner-Strasse 10, D-80333 Munich, Germany 4Corresponding authors. E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Aphanius pluristriatus (Jenkins, 1910) (Cyprinodontidae) is a poorly known species from Fasa, located in the Mond River drainage system, east of Shiraz, southern Iran. It has not been investigated since its first description, its validity has been questioned and a synonymy with A. sophiae (Heckel, 1849) has been suggested. In this study, we describe a new collection of Aphanius specimens from the Zarjan spring system, which is probably the same spring system from where Jenkins (1910) collected the type specimens of A. pluristriatus. The morphological characters of our new series of specimens are consistent with those of A. pluristriatus as originally described by Jenkins (1910). We emend the original description of A. pluristriatus and add morphometric and meristic data. A comparison with the related taxa A. sophiae, A. farsicus (for- mer A. persicus) and A. -

An Updated List of Taxonomy, Distribution and Conservation Status (Teleostei: Cyprinodontoidea)

Iran. J. Ichthyol. (March 2018), 5(1): 1–29 Received: January 5, 2018 © 2018 Iranian Society of Ichthyology Accepted: March 1, 2018 P-ISSN: 2383-1561; E-ISSN: 2383-0964 doi: 10.22034/iji.v5i1.267 http://www.ijichthyol.org Review Article Cyprinodontid fishes of the world: an updated list of taxonomy, distribution and conservation status (Teleostei: Cyprinodontoidea) Hamid Reza ESMAEILI1*, Tayebeh ASRAR1, Ali GHOLAMIFARD2 1Ichthyology and Molecular Systematics Research Laboratory, Zoology Section, Department of Biology, College of Sciences, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran. 2Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Lorestan University, 6815144316 Khorramabad, Iran. Email: [email protected] Abstract: This checklist aims to list all the reported cyprinodontid fishes (superfamily Cyprinodontoidea/pupfishes) of the world. It lists 141 species in 8 genera and 4 families. The most diverse family is Cyprinodontidae (54 species, 38%), followed by Orestiidae (45 species, 32%), Aphaniidae (39 species, 28%), and Cubanichthyidae (3 species, 2%). Among 141 listed species, 73 (51.8%) species are Not Evaluated (NE), 15 (10.6%) Least Concern (LC), 9 (6.4%) Vulnerable (VU), 3 (2.1%) Data Deficient (DD), 11 (7.8%) Critically Endangered (CR), 4 (2.8%) Near Threatened (NT), 18 (12.8%) Endangered (EN), 3 (2.1%) Extinct in the Wild (EW) and 5 (3.5%) Extinct of the Red List of IUCN. They inhabit in the fresh, brackish and marine waters of the United States, Middle America, the West Indies, parts of northern South America, North Africa, the Mediterranean Anatolian region, coastal areas of the Persian Gulf and Makran Sea (Oman Sea), the northern Arabian Sea east to Gujarat in India, and some endorheic basins of Iran, Pakistan and the Arabian Peninsula.