The Mystery of the Banded Killifish Fundulus Diaphanus Population Explosion: Where Did They All Come From?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission Gordon Myers, Executive Director

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission Gordon Myers, Executive Director March 1, 2016 Honorable Jimmy Dixon Honorable Chuck McGrady N.C. House of Representatives N.C. House of Representatives 300 N. Salisbury Street, Room 416B 300 N. Salisbury Street, Room 304 Raleigh, NC 27603-5925 Raleigh, NC 27603-5925 Senator Trudy Wade N.C. Senate 300 N. Salisbury Street, Room 521 Raleigh, NC 27603-5925 Dear Honorables: I am submitting this report to the Environmental Review Committee in fulfillment of the requirements of Section 4.33 of Session Law 2015-286 (H765). As directed, this report includes a review of methods and criteria used by the NC Wildlife Resources Commission on the State protected animal list as defined in G.S. 113-331 and compares them to federal and state agencies in the region. This report also reviews North Carolina policies specific to introduced species along with determining recommendations for improvements to these policies among state and federally listed species as well as nonlisted animals. If you have questions or need additional information, please contact me by phone at (919) 707-0151 or via email at [email protected]. Sincerely, Gordon Myers Executive Director North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission Report on Study Conducted Pursuant to S.L. 2015-286 To the Environmental Review Commission March 1, 2016 Section 4.33 of Session Law 2015-286 (H765) directed the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission (WRC) to “review the methods and criteria by which it adds, removes, or changes the status of animals on the state protected animal list as defined in G.S. -

Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Organochlorine Pesticide Concentrations in Whole Body Mummichog and Banded Killifish from the Anacostia River Watershed: 2018-2019

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Organochlorine Pesticide Concentrations in Whole Body Mummichog and Banded Killifish from the Anacostia River Watershed: 2018-2019 CBFO-C-20-01 Left: Mummichog, female (L), male (R); Right: Banded killifish, left two are males, right two are females. Photos: Fred Pinkney, USFWS U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Chesapeake Bay Field Office June 2020 Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Organochlorine Pesticide Concentrations in Whole Body Mummichog and Banded Killifish from the Anacostia River Watershed: 2018-2019 CBFO-C20-01 Prepared by Alfred E. Pinkney U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Chesapeake Bay Field Office Annapolis, MD and Elgin S. Perry Statistical Consultant Colonial Beach, VA Prepared for Dev Murali Government of the District of Columbia Department of Energy and Environment Washington, DC June 2020 ABSTRACT In 2018 and 2019, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Chesapeake Bay Field Office (CBFO) monitored polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) and organochlorine (OC) pesticide concentrations in whole body samples of forage fish. Fish were collected along the mainstem Anacostia River, Kingman Lake, five major tributaries, and (as a reference) a section of the Potomac River. Mummichog (Fundulus heteroclitus; referred to as MC in this report) and banded killifish (F. diaphanus BK) were chosen because of their high site fidelity and widespread presence in the watersheds. The objectives are to: 1) establish a pre-remedial baseline of these contaminants in fish from the Anacostia mainstem and major tributaries, Kingman Lake, and the Potomac River; 2) compare total PCB, total chlordane, and total DDT among sampling locations; and 3) interpret patterns in PCB homologs. -

Morphological and Genetic Comparative

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 79: 373- 383, 2008 Morphological and genetic comparative analyses of populations of Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis (Cyprinodontiformes:Goodeidae) from Central Mexico, with description of a new species Análisis comparativo morfológico y genético de diferentes poblaciones de Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis (Cyprinodontiformes:Goodeidae) del Centro de México, con la descripción de una especie nueva Domínguez-Domínguez Omar1*, Pérez-Rodríguez Rodolfo1 and Doadrio Ignacio2 1Laboratorio de Biología Acuática, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Fuente de las Rosas 65, Fraccionamiento Fuentes de Morelia, 58088 Morelia, Michoacán, México 2Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, José Gutiérrez Abascal 2, 28006 Madrid, España. *Correspondent: [email protected] Abstract. A genetic and morphometric study of populations of Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis (Bean, 1898) from the Lerma and Ameca basins and Cuitzeo, Zacapu and Chapala Lakes in Central Mexico was conducted. For the genetic analysis, 7 populations were sampled and 2 monophyletic groups were identifi ed with a genetic difference of DHKY= 3.4% (3-3.8%), one being the populations from the lower Lerma basin, Ameca and Chapala Lake, and the other populations from Zacapu and Cuitzeo Lakes. For the morphometric analysis, 4 populations were sampled and 2 morphotypes identifi ed, 1 from La Luz Spring in the lower Lerma basin and the other from Zacapu and Cuitzeo Lakes drainages. Using these 2 sources of evidence, the population from La Luz is regarded as a new species Zoogoneticus purhepechus sp. nov. _The new species differs from its sister species Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis_ in having a shorter preorbital distance (Prol/SL x = 0.056, SD = 0.01), longer dorsal fi n base length (DFL/SL x = 0.18, SD = 0.03) and 13-14 rays in the dorsal fi n. -

Deterministic Shifts in Molecular Evolution Correlate with Convergence to Annualism in Killifishes

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.09.455723; this version posted August 10, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Deterministic shifts in molecular evolution correlate with convergence to annualism in killifishes Andrew W. Thompson1,2, Amanda C. Black3, Yu Huang4,5,6 Qiong Shi4,5 Andrew I. Furness7, Ingo, Braasch1,2, Federico G. Hoffmann3, and Guillermo Ortí6 1Department of Integrative Biology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48823, USA. 2Ecology, Evolution & Behavior Program, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA. 3Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Entomology, & Plant Pathology, Mississippi State University, Starkville, MS 39759, USA. 4Shenzhen Key Lab of Marine Genomics, Guangdong Provincial Key Lab of Molecular Breeding in Marine Economic Animals, BGI Marine, Shenzhen 518083, China. 5BGI Education Center, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenzhen 518083, China. 6Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052, USA. 7Department of Biological and Marine Sciences, University of Hull, UK. Corresponding author: Andrew W. Thompson, [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.09.455723; this version posted August 10, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract: The repeated evolution of novel life histories correlating with ecological variables offer opportunities to test scenarios of convergence and determinism in genetic, developmental, and metabolic features. Here we leverage the diversity of aplocheiloid killifishes, a clade of teleost fishes that contains over 750 species on three continents. -

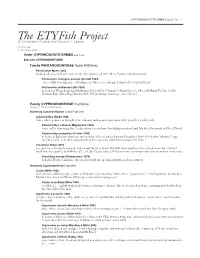

The Etyfish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J

CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3) · 1 The ETYFish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara COMMENTS: v. 3.0 - 13 Nov. 2020 Order CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3 of 4) Suborder CYPRINODONTOIDEI Family PANTANODONTIDAE Spine Killifishes Pantanodon Myers 1955 pan(tos), all; ano-, without; odon, tooth, referring to lack of teeth in P. podoxys (=stuhlmanni) Pantanodon madagascariensis (Arnoult 1963) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Madagascar, where it is endemic [extinct due to habitat loss] Pantanodon stuhlmanni (Ahl 1924) in honor of Franz Ludwig Stuhlmann (1863-1928), German Colonial Service, who, with Emin Pascha, led the German East Africa Expedition (1889-1892), during which type was collected Family CYPRINODONTIDAE Pupfishes 10 genera · 112 species/subspecies Subfamily Cubanichthyinae Island Pupfishes Cubanichthys Hubbs 1926 Cuba, where genus was thought to be endemic until generic placement of C. pengelleyi; ichthys, fish Cubanichthys cubensis (Eigenmann 1903) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Cuba, where it is endemic (including mainland and Isla de la Juventud, or Isle of Pines) Cubanichthys pengelleyi (Fowler 1939) in honor of Jamaican physician and medical officer Charles Edward Pengelley (1888-1966), who “obtained” type specimens and “sent interesting details of his experience with them as aquarium fishes” Yssolebias Huber 2012 yssos, javelin, referring to elongate and narrow dorsal and anal fins with sharp borders; lebias, Greek name for a kind of small fish, first applied to killifishes (“Les Lebias”) by Cuvier (1816) and now a -

BULLETIN of the FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM Biological Sciences

BULLETIN of the FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM Biological Sciences VOLUME 29 1983 NUMBER 1 A SYSTEMATIC STUDY OF TWO SPECIES COMPLEXES OF THE GENUS FUNDULUS (PISCES: CYPRINODONTIDAE) KENNETH RELYEA e UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA GAINESVILLE Numbers of the BULLETIN OF THE FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM, BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES, are published at irregular intervals. Volumes contain about 300 pages and are not necessarily completed in any one calendar year. OLIVER L. AUSTIN, JR., Editor RHODA J. BRYANT, Managing Editor Consultants for this issue: GEORGE H. BURGESS ~TEVEN P. (HRISTMAN CARTER R. GILBERT ROBERT R. MILLER DONN E. ROSEN Communications concerning purchase or exchange of the publications and all manuscripts should be addressed to: Managing Editor, Bulletin; Florida State Museum; University of Florida; Gainesville, FL 32611, U.S.A. Copyright © by the Florida State Museum of the University of Florida This public document was promulgated at an annual cost of $3,300.53, or $3.30 per copy. It makes available to libraries, scholars, and all interested persons the results of researches in the natural sciences, emphasizing the circum-Caribbean region. Publication dates: 22 April 1983 Price: $330 A SYSTEMATIC STUDY OF TWO SPECIES COMPLEXES OF THE GENUS FUNDULUS (PISCES: CYPRINODONTIDAE) KENNETH RELYEAl ABSTRACT: Two Fundulus species complexes, the Fundulus heteroctitus-F. grandis and F. maialis species complexes, have nearly identical Overall geographic ranges (Canada to north- eastern Mexico and New England to northeastern Mexico, respectively; both disjunctly in Yucatan). Fundulus heteroclitus (Canada to northeastern Florida) and F. grandis (northeast- ern Florida to Mexico) are valid species distinguished most readily from one another by the total number of mandibular pores (8'and 10, respectively) and the long anal sheath of female F. -

Information on the NCWRC's Scientific Council of Fishes Rare

A Summary of the 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes in North Carolina Submitted by Bryn H. Tracy North Carolina Division of Water Resources North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources Raleigh, NC On behalf of the NCWRC’s Scientific Council of Fishes November 01, 2014 Bigeye Jumprock, Scartomyzon (Moxostoma) ariommum, State Threatened Photograph by Noel Burkhead and Robert Jenkins, courtesy of the Virginia Division of Game and Inland Fisheries and the Southeastern Fishes Council (http://www.sefishescouncil.org/). Table of Contents Page Introduction......................................................................................................................................... 3 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes In North Carolina ........... 4 Summaries from the 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes in North Carolina .......................................................................................................................... 12 Recent Activities of NCWRC’s Scientific Council of Fishes .................................................. 13 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part I, Ohio Lamprey .............................................. 14 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part II, “Atlantic” Highfin Carpsucker ...................... 17 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part III, Tennessee Darter ...................................... 20 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Gene Expression After Freshwater Transfer in Gills and Opercular Epithelia of Killifish: Insight Into Divergent Mechanisms of Ion Transport Graham R

The Journal of Experimental Biology 208, 2719-2729 2719 Published by The Company of Biologists 2005 doi:10.1242/jeb.01688 Gene expression after freshwater transfer in gills and opercular epithelia of killifish: insight into divergent mechanisms of ion transport Graham R. Scott1,*, James B. Claiborne2, Susan L. Edwards2,3, Patricia M. Schulte1 and Chris M. Wood4 1Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver BC, Canada V6T 1Z4, 2Department of Biology, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA 30460-8042, USA, 3Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD 4879, Australia and 4Department of Biology, McMaster University, Hamilton ON, Canada L8S 4K1 *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 17 May 2005 Summary We have explored the molecular basis for differences in epithelium, NHE2 was not expressed; furthermore, physiological function between the gills and opercular Na+,K+-ATPase activity was unchanged after transfer to epithelium of the euryhaline killifish Fundulus freshwater, CA2 mRNA levels decreased, and NHE3 levels heteroclitus. These tissues are functionally similar in increased. Consistent with their functional similarities in seawater, but in freshwater the gills actively absorb Na+ seawater, killifish gills and opercular epithelium expressed – + + + + – but not Cl , whereas the opercular epithelium actively Na ,K -ATPase α1a, Na ,K ,2Cl cotransporter 1 absorbs Cl– but not Na+. These differences in freshwater (NKCC1), cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance physiology are likely due to differences in absolute levels regulator (CFTR) Cl– channel and the signalling protein of gene expression (measured using real-time PCR), as 14-3-3a at similar absolute levels. Furthermore, NKCC1 several proteins important for Na+ transport, namely and CFTR were suppressed equally in each tissue after Na+,H+-exchanger 2 (NHE2), carbonic anhydrase 2 (CA2), freshwater transfer, and 14-3-3a mRNA increased in both. -

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019)

IUCN Red List version 2019-3: Table 7 Last Updated: 10 December 2019 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2018 (IUCN Red List version 2018-2) and 2019 (IUCN Red List version 2019-3) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered [CR(PE) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct), CR(PEW) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct in the Wild)], EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2018) List (2019) change version Category -

The African Turquoise Killifish: a Model for Exploring Vertebrate Aging and Diseases in the Fast Lane

Downloaded from symposium.cshlp.org on June 11, 2016 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press The African Turquoise Killifish: A Model for Exploring Vertebrate Aging and Diseases in the Fast Lane 1 1,2 ITAMAR HAREL AND ANNE BRUNET 1Department of Genetics, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305 2Glenn Laboratories for the Biology of Aging at Stanford, Stanford, California 94305 Correspondence: [email protected] Why and how organisms age remains a mystery, and it defines one of the biggest challenges in biology. Aging is also the primary risk factor for many human pathologies, such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases. Thus, manipulating the aging rate and potentially postponing the onset of these devastating diseases could have a tremendous impact on human health. Recent studies, relying primarily on nonvertebrate short-lived model systems, have shown the importance of both genetic and environmental factors in modulating the aging rate. However, relatively little is known about aging in vertebrates or what processes may be unique and specific to these complex organisms. Here we discuss how advances in genomics and genome editing have significantly expanded our ability to probe the aging process in a vertebrate system. We highlight recent findings from a naturally short-lived vertebrate, the African turquoise killifish, which provides an attractive platform for exploring mechanisms underlying vertebrate aging and age-related diseases. MODELING AGING IN THE ing vertebrate aging and age-related diseases (Harel et al. LABORATORY 2015). Aging research has greatly benefited from investigating short-lived nonvertebrate models (Fig. 1A), specifically THE AFRICAN TURQUOISE KILLIFISH yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), worm (Caenorhabdi- tis elegans), and fly (Drosophila melanogaster). -

The Neotropical Genus Austrolebias: an Emerging Model of Annual Killifishes Nibia Berois1, Maria J

lopmen ve ta e l B D io & l l o l g e y C Cell & Developmental Biology Berois, et al., Cell Dev Biol 2014, 3:2 ISSN: 2168-9296 DOI: 10.4172/2168-9296.1000136 Review Article Open Access The Neotropical Genus Austrolebias: An Emerging Model of Annual Killifishes Nibia Berois1, Maria J. Arezo1 and Rafael O. de Sá2* 1Departamento de Biologia Celular y Molecular, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de la República, Montevideo, Uruguay 2Department of Biology, University of Richmond, Richmond, Virginia, USA *Corresponding author: Rafael O. de Sá, Department of Biology, University of Richmond, Richmond, Virginia, USA, Tel: 804-2898542; Fax: 804-289-8233; E-mail: [email protected] Rec date: Apr 17, 2014; Acc date: May 24, 2014; Pub date: May 27, 2014 Copyright: © 2014 Rafael O. de Sá, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Annual fishes are found in both Africa and South America occupying ephemeral ponds that dried seasonally. Neotropical annual fishes are members of the family Rivulidae that consist of both annual and non-annual fishes. Annual species are characterized by a prolonged embryonic development and a relatively short adult life. Males and females show striking sexual dimorphisms, complex courtship, and mating behaviors. The prolonged embryonic stage has several traits including embryos that are resistant to desiccation and undergo up to three reversible developmental arrests until hatching. These unique developmental adaptations are closely related to the annual fish life cycle and are the key to the survival of the species.