Snapshots of Yucatec Maya Language Practices: Language Policy and Planning Activities in the Yucatán Peninsula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Historical Journal

UCLA UCLA Historical Journal Title "May They Not Be Fornicators Equal to These Priests": Postconquest Yucatec Maya Sexual Attitudes Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9wm6k90j Journal UCLA Historical Journal, 12(0) ISSN 0276-864X Authors Restall, Matthew Sigal, Pete Publication Date 1992 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California "May They Not Be Fornicators Equal to These Priests": Postconquest Yucatec Maya Sexual Attitudes^ Matthew Restall and Pete Sigal ten cen ah hahal than cin iialic techex hebaxile a uohelex yoklal P^^ torres p^ Dias cabo de escuadra P^ granado sargento yetel p^ maldonado layoh la ma hahal caput sihil ma hahal confisar ma hahal estremacion ma hahal misa cu yalicobi maix tan u yemel hahal Dios ti lay ostia licil u yalicob misae tumenel tutuchci u cepob sansamal kin chenbel u chekic iieyob cu tuculicob he tu yahalcabe manal tuil u kabob licil u baxtic u ueyob he p^ torrese chenbel u pel kakas cisin Rita box cu baxtic y u moch kabi mai moch u cep ualelob ix >oc cantiil u mehenob ti lay box cisin la baixan p^ Diaz cabo de escuadra tu kaba u cumaleil antonia aluarado xbolonchen tan u lolomic u pel u cumale tiitan tulacal cah y p^ granado sargento humab akab tan u pechic u pel manuela pacheco hetun p^ maldonadoe tun>oc u lahchekic u mektanilobe uay cutalel u chucbes u cheke yohel tulacal cah ti cutalel u ah semana uinic y xchup ti pencuyute utial yoch pelil p^ maldonado xpab gomes u kabah chenbel Padresob ian u sipitolal u penob matan u than yoklalob uaca u ment utzil 92 Indigenous Writing in the Spanish Indies mageuale tusebal helelac ium cura u >aic u tzucte hetun lae tutac u kabob yetel pel lay yaxcacbachob tumen u pen cech penob la caxuob yal misa bailo u yoli Dios ca oc inglesob uaye ix ma aci ah penob u padreilobi hetun layob lae tei hunima u topob u yit uinicobe yoli Dios ca haiac kak tu pol cepob amen ten yumil ah hahal than. -

The Political Economy of Linguistic and Social Exchange Among The

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Mayas, Markets, and Multilingualism: The Political Economy of Linguistic and Social Exchange in Cobá, Quintana Roo, Mexico Stephanie Joann Litka Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES MAYAS, MARKETS, AND MULTILINGUALISM: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LINGUISTIC AND SOCIAL EXCHANGE IN COBÁ, QUINTANA ROO, MEXICO By STEPHANIE JOANN LITKA A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Copyright 2012 Stephanie JoAnn Litka All Rights Reserved Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Stephanie JoAnn Litka defended this dissertation on October 28, 2011 . The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Uzendoski Professor Directing Dissertation Robinson Herrera University Representative Joseph Hellweg Committee Member Mary Pohl Committee Member Gretchen Sunderman Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the [thesis/treatise/dissertation] has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For the people of Cobá, Mexico Who opened their homes, jobs, and hearts to me iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My fieldwork in Cobá was generously funded by the National Science Foundation, the Florida State University Center for Creative Research, and the Tinker Field Grant. I extend heartfelt gratitude to each organization for their support. In Mexico, I thank first and foremost the people of Cobá who welcomed me into their community over twelve years ago. I consider this town my second home and cherish the life-long friendships that have developed during this time. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Toward a Comprehensive Model For

Toward a Comprehensive Model for Nahuatl Language Research and Revitalization JUSTYNA OLKO,a JOHN SULLIVANa, b, c University of Warsaw;a Instituto de Docencia e Investigación Etnológica de Zacatecas;b Universidad Autonóma de Zacatecasc 1 Introduction Nahuatl, a Uto-Aztecan language, enjoyed great political and cultural importance in the pre-Hispanic and colonial world over a long stretch of time and has survived to the present day.1 With an estimated 1.376 million speakers currently inhabiting several regions of Mexico,2 it would not seem to be in danger of extinction, but in fact it is. Formerly the language of the Aztec empire and a lingua franca across Mesoamerica, after the Spanish conquest Nahuatl thrived in the new colonial contexts and was widely used for administrative and religious purposes across New Spain, including areas where other native languages prevailed. Although the colonial language policy and prolonged Hispanicization are often blamed today as the main cause of language shift and the gradual displacement of Nahuatl, legal steps reinforced its importance in Spanish Mesoamerica; these include the decision by the king Philip II in 1570 to make Nahuatl the linguistic medium for religious conversion and for the training of ecclesiastics working with the native people in different regions. Members of the nobility belonging to other ethnic groups, as well as numerous non-elite figures of different backgrounds, including Spaniards, and especially friars and priests, used spoken and written Nahuatl to facilitate communication in different aspects of colonial life and religious instruction (Yannanakis 2012:669-670; Nesvig 2012:739-758; Schwaller 2012:678-687). -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Was There Hebrew Language in Ancient America? an Interview with Brian Stubbs

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 9 Number 2 Article 9 7-31-2000 Was There Hebrew Language in Ancient America? An Interview with Brian Stubbs Brian Stubbs Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Stubbs, Brian (2000) "Was There Hebrew Language in Ancient America? An Interview with Brian Stubbs," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 9 : No. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol9/iss2/9 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Was There Hebrew Language in Ancient America? An Interview with Brian Stubbs Author(s) Brian Stubbs and John L. Sorenson Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 9/2 (2000): 54–63, 83. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract In an interview with John L. Sorenson, linguist Brian Stubbs discusses the evidence he has used to establish that at least one language family in Mesoamerica is related to Semitic languages. Stubbs explains how his studies of Near Eastern languages, coupled with his studies of Uto-Aztecan, helped him find related word pairs in the two language families. The evidence for a link between Uto-Aztecan and Semitic languages, or even Egyptian or Arabic, is still tentative, although the evidence includes all the standard requirements of comparative or historical linguistic research: sound correspondences or con- sistent sound shifts, morphological correspondences, and a substantial lexicon consisting of as many as 1,000 words that exemplify those correspondences. -

The Genetic History of the Otomi in the Central Mexican Valley

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Anthropology Senior Theses Department of Anthropology Spring 2013 The Genetic History Of The Otomi In The Central Mexican Valley Haleigh Zillges University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_seniortheses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Zillges, Haleigh, "The Genetic History Of The Otomi In The Central Mexican Valley" (2013). Anthropology Senior Theses. Paper 133. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_seniortheses/133 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Genetic History Of The Otomi In The Central Mexican Valley Abstract The Otomí, or Hñäñhü, is an indigenous ethnic group in the Central Mexican Valley that has been historically marginalized since before Spanish colonization. To investigate the extent by which historical, geographic, linguistic, and cultural influences shaped biological ancestry, I analyzed the genetic variation of 224 Otomí individuals residing in thirteen Otomí villages. Results indicate that the majority of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplotypes belong to the four major founding lineages, A2, B2, C1, and D1, reflecting an overwhelming lack of maternal admixture with Spanish colonizers. Results also indicate that at an intra-population level, neither geography nor linguistics played a prominent role in shaping maternal biological ancestry. However, at an inter-population level, geography was found to be a more influential determinant. Comparisons of Otomí genetic variation allow us to reconstruct the ethnic history of this group, and to place it within a broader-based Mesoamerican history. Disciplines Anthropology This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_seniortheses/133 THE GENETIC HISTORY OF THE OTOMI IN THE CENTRAL MEXICAN VALLEY By Haleigh Zillges In Anthropology Submitted to the Department of Anthropology University of Pennsylvania Thesis Advisor: Dr. -

1 Language Use, Language Change and Innovation In

LANGUAGE USE, LANGUAGE CHANGE AND INNOVATION IN NORTHERN BELIZE CONTACT SPANISH By OSMER EDER BALAM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and support from many people, who have been instrumental since the inception of this seminal project on contact Spanish outcomes in Northern Belize. First and foremost, I am thankful to Dr. Mary Montavon and Prof. Usha Lakshmanan, who were of great inspiration to me at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale. Thank you for always believing in me and motivating me to pursue a PhD. This achievement is in many ways also yours, as your educational ideologies have profoundly influenced me as a researcher and educator. I am indebted to my committee members, whose guidance and feedback were integral to this project. In particular, I am thankful to my adviser Dr. Gillian Lord, whose energy and investment in my education and research were vital for the completion of this dissertation. I am also grateful to Dr. Ana de Prada Pérez, whose assistance in the statistical analyses was invaluable to this project. I am thankful to my other committee members, Dr. Benjamin Hebblethwaite, Dr. Ratree Wayland, and Dr. Brent Henderson, for their valuable and insighful comments and suggestions. I am also grateful to scholars who have directly or indirectly contributed to or inspired my work in Northern Belize. These researchers include: Usha Lakshmanan, Ad Backus, Jacqueline Toribio, Mark Sebba, Pieter Muysken, Penelope Gardner- Chloros, and Naomi Lapidus Shin. -

Maya and Nahuatl in the Teaching of Spanish

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Faculty Publications World Languages and Literatures 3-1-2007 Maya and Nahuatl in the Teaching of Spanish Anne Fountain San Jose State University, [email protected] Catherine Fountain Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/world_lang_pub Part of the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Anne Fountain and Catherine Fountain. "Maya and Nahuatl in the Teaching of Spanish" From Practice to Profession: Dimension 2007 (2007): 63-77. This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the World Languages and Literatures at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 6 Maya and Nahuatl in the Teaching of Spanish: Expanding the Professional Perspective Anne Fountain San Jose State University Catherine Fountain Appalachian State University Abstract Indigenous languages of the Americas are spoken by millions of people 500 years after the initial period of European conquest. The people who speak these languages and the customs they continue to practice form a rich cultural texture in many parts of Spanish America and can be important components of an instructor’s Standards-based teaching. This article discusses the influence of Maya and Nahuatl languages and cultures on the language, literature, and history of Mexico and Central America. Examples of this influence range from lexical and phonological traits of Mexican Spanish to the indigenous cultures and worldviews conveyed in texts as varied as the Mexican soap opera “Barrera de Amor” and the stories by Rosario Castellanos of Mexico and Miguel Angel Asturias of Gua temala. -

Common Questions About Nahuatl Page 1 of 4

Common questions about Nahuatl Page 1 of 4 [versión en español] This page uses Unicode Common questions about Nahuatl z Which is the correct form: Nahua, Nahuatl, Nahuat, or Nahual? z Why does Nahuatl have such long words? z What languages are related to Nahuatl? z Why do you hear so many Spanish words when modern Nahuatl is spoken? z Why do so many place-names and language names in Mexico and Central America come from Nahuatl, even when Nahuatl is not spoken in the area? z Why do so many place-names in Mexico end with - tla, -pa, -ca, -cingo, etc.? (Green underlined words are links to definitions.) Which is the correct form: Nahua, Nahuatl, Nahuat, or Nahual? Each of these terms has its correct usage. The best-known and most widely-spoken variants of Nahuatl have a phoneme /tl/ (phonetically [tl]), which is the modern reflex of proto-Uto-Aztecan */t/ where it was followed by */a/. In those variants the word would be "Nahuatl", and it is natural that that name is also applied to the family as a whole, naming it for its most best-known members. Other Nahuatl languages retained the original */t/ sound (or re-simplified the */tl/ to /t/); others simplified the */tl/ to /l/. Because of this, some analysts have made a three-way classification, speaking of "Nahuatl", "Nahuat", and "Nahual" languages, and sometimes "Nahua" is used to specify the language family as a whole. The fact that "Nahua" is easier to pronounce than "Nahuatl" may also have something to do with its attractiveness as a name. -

The Catholic Church and the Preservation of Mesoamerican Archives: an Assessment

THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE PRESERVATION OF MESOAMERICAN ARCHIVES: AN ASSESSMENT BY MICHAEL ARBAGI ABSTRACT: This article examines the role of the Catholic Church in the destruction and eventual recreation of the manuscripts, oral histories, and other records of the indigenous civilizations of Mesoamerica (the nations of modern Mexico and Central America). It focuses on the time frame immediately after the conquest of Mesoamerica by the Spanish. The article addresses this topic from an archival, rather than histori- cal, point of view. Destruction and Recreation The invasion and conquest of Mexico by a Spanish expedition under the leadership of Hernán Cortés could be described as the most consequential event in the history of Latin America. The events read like a work of fiction: a band of adventurers from European Spain brought the language, religion, and other institutions of their nation to established pre-Columbian societies which had rich traditions of their own. The technologically and militarily superior Spanish, along with their indigenous allies, conquered the then-dominant power in the region, the Aztec Empire. Nonetheless, pre-Columbian cultures and languages survived to influence and enrich their Spanish conquerors, ultimately forming the complex and fascinating modern nations of Mexico and Central America, or “Mesoamerica.” The Spanish invaders and Catholic clergy who accompanied them destroyed many of the old documents and archives of the civilizations which preceded them. They carried out this destruction often for military reasons (to demoralize the indigenous fighters opposing them), or, in other cases, on religious grounds (to battle what they regarded as the false faith of the native peoples). -

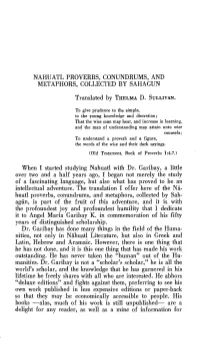

Nahuatl Proverbs, Conundrums, and Metaphors, Collected by Sahagun

NAHUATL PROVERBS, CONUNDRUMS, AND METAPHORS, COLLECTED BY SAHAGUN Translated hy THELMA D. SULLIVAN. To give prudence to the simple, to the young knowledge and discretion; That the wise man may hear, and increase in learning, and the man of understanding may attam unto wise counsels; To understand a proverb and a figure, the words oí the wise and their dark sayings. (Old Testament, Book of Proverbs 1:4-7.) When 1 started studying Nahuatl with Dr. Garihay, a liule over two and a haH years ago, 1 hegan not merely the study of a fascinating language, hut also what has proved to he an inteHectual adventure. The translation 1 offer here of the N á huatl proverhs, conundrums, and metaphors, collected hy Sah agún, is part of the fruit of this adventure, and it is with the profoundest joy and profoundest humility that 1 dedicate it to Angel María Garihay K. in commemoration of his fifty years of distinguished scholarship. Dr. Garihay has done many things in the field of the Huma nities, not only in Náhuatl Lite rature , hut also in Greek and Latin, Hehrew and Aramaic. However, there is one thing that he has not done, and it is this one thing that has made his work outstanding. He has never taken the "human" out of the Hu manities. Dr. Garihay is not a "scholar's scholar," he is aH the world's scholar, and the knowledge that he has garnered in his lifetime he freely shares with all who are interested. He ahhors "deluxe editions" and fights against them, preferring to see his own work puhlished in less expensive editions or paper-hack so that they may he economicaHy accessihle to people.