WRITING the HISTORY of MODERN CHEMISTRY* Peter J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sequencing As a Way of Work

Edinburgh Research Explorer A new insight into Sanger’s development of sequencing Citation for published version: Garcia-Sancho, M 2010, 'A new insight into Sanger’s development of sequencing: From proteins to DNA, 1943-77', Journal of the History of Biology, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 265-323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10739-009- 9184-1 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1007/s10739-009-9184-1 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of the History of Biology Publisher Rights Statement: © Garcia-Sancho, M. (2010). A new insight into Sanger’s development of sequencing: From proteins to DNA, 1943-77. Journal of the History of Biology, 43(2), 265-323. 10.1007/s10739-009-9184-1 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 THIS IS AN ADVANCED DRAFT OF A PUBLISHED PAPER. REFERENCES AND QUOTATIONS SHOULD ALWAYS BE MADE TO THE PUBLISHED VERION, WHICH CAN BE FOUND AT: García-Sancho M. -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

RICHARD LAWRENCE MILLINGTON SYNGE BA, Phd(Cantab), Hondsc(Aberd), Hondsc(E.Anglia), Hon Dphil(Uppsala), FRS Nobel Laureate 1952

RICHARD LAWRENCE MILLINGTON SYNGE BA, PhD(Cantab), HonDSc(Aberd), HonDSc(E.Anglia), Hon DPhil(Uppsala), FRS Nobel Laureate 1952 R L M Synge was elected FRSE in 1963. He was born in West Kirby, Cheshire, on 28 October 1914, the son of Katherine (née Swan) and Lawrence Millington Synge, a Liverpool Stockbroker. The family was known to be living in Bridgenorth (Salop) in the early sixteenth century. At that time the name was Millington and there is a story that a member of the family from Millington Hall in Rostherne (Cheshire) sang so beautifully before King Henry VIII that he was told to take the name Synge. There have been various spellings of the name and in the nineteenth century the English branch settled on Sing which they retained until 1920 when both R M and L M Sing (Dick's uncle and father respectively) changed their names by deed poll to Synge. In the 19th and 20th centuries the Sing/Synge family played a considerable part in the life of Liverpool and Dick's father was High Sheriff of Cheshire in 1954. Dick was educated at Old Hall, a prep school in Wellington (Salop) and where he became renowned for his ability in Latin and Greek, subjects which he continued to study with such success at Winchester that in December 1931 when, just turned 17, he was awarded an Exhibition in Classics by Trinity College, Cambridge. His intention was to study science and Trinity allowed Dick to switch from classics to the Natural Sciences Tripos. To prepare for the change he returned to Winchester in January 1932 to study science for the next 18 months and was awarded the senior science prize for 1933. -

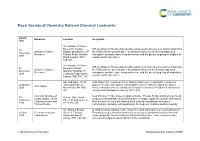

RSC Branding

Royal Society of Chemistry National Chemical Landmarks Award Honouree Location Inscription Date The Institute of Cancer Research, Chester ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Institute of Cancer Beatty Laboratories, 237 the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Research Fulham Road, Chelsea carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Road, London, SW3 ovarian and breast cancer. 6JB, UK The Institute of Cancer ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Research, Royal Institute of Cancer the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Marsden Hospital, 15 Research carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Cotswold Road, Sutton, ovarian and breast cancer. London, SM2 5NG, UK Ape and Apple, 28-30 John Dalton Street was opened in 1846 by Manchester Corporation in honour of 26 October John Dalton Street, famous chemist, John Dalton, who in Manchester in 1803 developed the Atomic John Dalton 2016 Manchester, M2 6HQ, Theory which became the foundation of modern chemistry. President of Manchester UK Literary and Philosophical Society 1816-1844. Chemical structure of Near this site in 1903, James Colquhoun Irvine, Thomas Purdie and their team found 30 College Gate, North simple sugars, James a way to understand the chemical structure of simple sugars like glucose and lactose. September Street, St Andrews, Fife, Colquhoun Irvine and Over the next 18 years this allowed them to lay the foundations of modern 2016 KY16 9AJ, UK Thomas Purdie carbohydrate chemistry, with implications for medicine, nutrition and biochemistry. -

Los Premios Nobel De Química

Los premios Nobel de Química MATERIAL RECOPILADO POR: DULCE MARÍA DE ANDRÉS CABRERIZO Los premios Nobel de Química El campo de la Química que más premios ha recibido es el de la Quí- mica Orgánica. Frederick Sanger es el único laurea- do que ganó el premio en dos oca- siones, en 1958 y 1980. Otros dos también ganaron premios Nobel en otros campos: Marie Curie (física en El Premio Nobel de Química es entregado anual- 1903, química en 1911) y Linus Carl mente por la Academia Sueca a científicos que so- bresalen por sus contribuciones en el campo de la Pauling (química en 1954, paz en Física. 1962). Seis mujeres han ganado el Es uno de los cinco premios Nobel establecidos en premio: Marie Curie, Irène Joliot- el testamento de Alfred Nobel, en 1895, y que son dados a todos aquellos individuos que realizan Curie (1935), Dorothy Crowfoot Ho- contribuciones notables en la Química, la Física, la dgkin (1964), Ada Yonath (2009) y Literatura, la Paz y la Fisiología o Medicina. Emmanuelle Charpentier y Jennifer Según el testamento de Nobel, este reconocimien- to es administrado directamente por la Fundación Doudna (2020) Nobel y concedido por un comité conformado por Ha habido ocho años en los que no cinco miembros que son elegidos por la Real Aca- demia Sueca de las Ciencias. se entregó el premio Nobel de Quí- El primer Premio Nobel de Química fue otorgado mica, en algunas ocasiones por de- en 1901 al holandés Jacobus Henricus van't Hoff. clararse desierto y en otras por la Cada destinatario recibe una medalla, un diploma y situación de guerra mundial y el exi- un premio económico que ha variado a lo largo de los años. -

AUTUMN 2012 8/10/12 13:17 Page 1

sip AUTUMN 2012 8/10/12 13:17 Page 1 SCIENCE IN PARLIAMENT A proton collides with a proton The Higgs boson appears at last sip AUTUMN 2012 The Journal of the Parliamentary and Scientific Committee www.scienceinparliament.org.uk sip AUTUMN 2012 8/10/12 13:17 Page 2 Physics for All Science and engineering students are important for the future of the UK IOP wants to see more people studying physics www.iop.org / 35 $' 3$5/, $ LQGG sip AUTUMN 2012 8/10/12 13:17 Page 3 Last years's winter of discontent was indeed made SCIENCE IN PARLIAMENT glorious summer by several sons and daughters of York. So many medals in the Olympics were won by scions of Yorkshire that the county claimed tenth place in the medals table, something hard to accept on my side of the Pennines! As well as being fantastic athletic performances the Olympics and Paralympics were stunning demonstrations of the efficiency of UK engineering, and sip the imagination of British science. The Journal of the Parliamentary and Scientific Surely we have good reason to be all eagerly awaiting Andrew Miller MP Committee. Chairman, Parliamentary The Committee is an Associate Parliamentary the announcements from Stockholm of this year's Nobel and Scientific Group of members of both Houses of Prizes? Surely the Higgs boson will be recognised? John Committee Parliament and British members of the European Parliament, representatives of Ellis recently eloquently described the "legacy" of the scientific and technical institutions, industrial hadron collider and we would be missing an important organisations and universities. -

Leading Research for Better Health

< Contents > Contents Please click on the > to go directly to the page. > Introducing the MRC >AchievementsIntroducing thetimeline MRC Achievements>1913 to 1940s timeline >1950s to 1980s >1913 to 1940s >1990s to 2006 >1950s to 1980s >1990s to 2006 > Leading research for better health >NobelLeading Prize resear timelinech for better health Nobel>1929 Prizeto 1952 timeline >1953 to 1962 >1929 to 1952 >1972 to 1984 >1953 to 1962 >1997 to 2003 >1972 to 1984 1997 to 2003 >MRC research over the decades MRC> From resear discochvery over to healthcare:the decades translational research > EvidenceFrom discovery for best to pr healthcareactice: clinical — translational trials research > EvidencePublic health for bestresearch practice: clinical trials > PubDNAlic revhealtholution research > ReducingDNA rev olutionsmoking: preventing deaths > ReducingTherapeutic smoking: antibodiespreventing deaths > TherapeuticReducing deaths antibodies from infections in Africa > ReducingPreventing deaths heart fromdisease infections in Africa > PrevMedicalenting imaging: hearttransformingdisease diagnosis > MedicalCutting childimaging: leukaemia transforming deaths diagnosis > Cutting child leukaemia deaths < Click on any link to go< directly Contentsto a page >> < Contents > < Contents > < Contents > < Contents > Leading research for better health The most important part of the MRC’s mission trials, such as those on the use of statins to lower is to encourage and support high-quality research cholesterol and on vaccines in Africa.The MRC with the aim of improving human health.The MRC is the UK’s largest public funder of clinical trials is committed to supporting research across the and it supports some of the most productive entire spectrum of the biomedical and clinical and ambitious epidemiological studies in the world, sciences. We are proud of our international including the UK Biobank. -

화학적 진화 Introduction

우주와 생명 제 10강 화학적 진화 INTRODUCTION Science 117, 528-529, 1953 가능한 태초 지구 조건에서의 아미노산 생성 A Production Of Amino Acids Under Possible Primitive Earth Conditions 밀러 Stanley L. Miller G. H. Jones Chemical Laboratory University of Chicago Chicago, Illinois INTRODUCTION Stanley L. Miller, A Production of Amino Acids under Possible Primitive Earth Conditions, Science, New Series, Vol. 117, Issue 3046, May 15. 1953, p.528 - 529 10-1 밀러의 반응물(Miller’s Reactants) 생명의 기반으로 작용하는 유기화합물들이 지구의 대기가 이산화탄소, 질소, 산소, 물 대신 메탄, 암모니아, 물, 그리고 수소로 이루어졌을 때 만들어졌다는 생각은 오파린에 의해 제안되었고, 최근에 유리와 버날에 의해 강조되었다. The idea that the organic compounds that serve as the basis of life were formed when the earth had an atmosphere of methane, ammonia, water, and hydrogen instead of carbon dioxide, nitrogen, oxygen, and water was suggested by Oparin and has been given emphasis recently by Urey and Bernal. 10-1 밀러의 반응물(Miller’s Reactants) <출처> <출처> <출처> http://www.pensament.com/ https://upload.wikimedia.org/ http://79.170.40.183/grahamste filoxarxa/imatges/Oparin.jpg wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/ venson.me.uk/images/stories/be 2e/Harold_Urey.jpg/200px- rnaljd.jpg Harold_Urey.jpg 오파린 유리 버날 Alexander Oparin Harold Urey John Desmond Bernal 1894-1980 1893-1981 1901-1971 10-1 밀러의 반응물(Miller’s Reactants) 우주의 원자 존재 비 우주의 분자 존재 비 (수소 원자의 개수를 100만이라고 하면) (수소 원자의 개수를 100만이라고 하면) H 1,000,000 He 80,000 H2 CO N2 H2O 10 – 10,000 O 840 C 560 HCN CO2 NH3 ~ 1 N 95 CH4 < 1 밀러가 사용한 네 가지 물질은 우주에 풍부하면서 단일결합 만으로 이루어진 분자들이다. -

Lista Över Nobelpristagare

Fysiologi SNo År Fysik Kemi eller Litteratur Fred Ekonomi medicin Wilhelm Jacobus Emil von Sully Henry Dunant; 1 1901 Conrad Henricus van 't Behring Prudhomme Frédéric Passy Röntgen Hoff Hendrik Hermann Emil Theodor Élie Ducommun; 2 1902 Lorentz; Ronald Ross Fischer Mommsen Albert Gobat Pieter Zeeman Henri Becquerel; Svante Niels Ryberg Bjørnstjerne 3 1903 Randal Cremer Pierre Curie; Arrhenius Finsen Bjørnson Marie Curie Frédéric Ivan William Mistral; Institut de droit 4 1904 Lord Rayleigh Petrovich Ramsay José international Pavlov Echegaray Adolf von Henryk 5 1905 Philipp Lenard Robert Koch Bertha von Suttner Baeyer Sienkiewicz Camillo Golgi; Giosuè 6 1906 J. J. Thomson Henri Moissan Santiago Theodore Roosevelt Carducci Ramón y Cajal Albert A. Alphonse Rudyard Ernesto Moneta; 7 1907 Eduard Buchner Michelson Laveran Kipling Louis Renault Ilya Ilyich Rudolf Gabriel Ernest Klas Pontus Arnoldson; 8 1908 Mechnikov; Christoph Lippmann Rutherford Fredrik Bajer Paul Ehrlich Eucken Ferdinand Auguste Beernaert; Braun; Wilhelm Theodor Selma 9 1909 Paul Henri d'Estournelles Guglielmo Ostwald Kocher Lagerlöf de Constant Marconi Johannes Albrecht 10 1910 Diderik van Otto Wallach Paul Heyse International Peace Bureau Kossel der Waals Tobias Michael Carel Allvar Maurice 11 1911 Wilhelm Wien Marie Curie Asser; Gullstrand Maeterlinck Alfred Fried Victor Grignard; Gerhart 12 1912 Gustaf Dalén Alexis Carrel Elihu Root Paul Sabatier Hauptmann Heike Charles Rabindranath 13 1913 Kamerlingh Alfred Werner Henri La Fontaine Richet Tagore Onnes Theodore Robert -

Sesion Ordinaria De La Comision De Gobierno Del Dia 26 De Junio De 2.003

SESION ORDINARIA DE LA COMISION DE GOBIERNO DEL DIA 26 DE JUNIO DE 2.003 SEÑORES ASISTENTES En el Salón de Sesio- Presidente: nes de la Casa Consistorial D. Pedro Castro Vázquez. del Ilustrísimo Ayuntamien- to de Getafe, siendo las Miembros: diez horas y treinta minu- P.S.O.E.: tos del día veintiséis de D. Fco. David Lucas Parrón. junio del año dos mil tres, Dª.Carmen Duque Revuelta. se reunieron en sesión or- D. Fco. Santos Vázquez Rabaz. dinaria, en segunda convo- D. Fernando Tena Ramiro. catoria, previamente convo- Dª.Mónica Medina Asperilla. cados al efecto, los miem- D. David Castro Valero. bros de la Comisión de Go- D. J. Manuel Vázquez Sacristán. bierno que al margen se expresan, bajo la Presiden- I.U.: cia del Sr. Alcalde Don Dª.Laura Lizaga Contreras. Pedro Castro Vázquez, pre- D. Ignacio Sánchez Coy. sente la Interventora Doña María del Carmen Miralles Interventora: Huete y actuando como Se- Dª.Mª. Carmen Miralles Huete. cretaria Doña Concepción Muñoz Yllera. Secretaria: Dª. Concepción Muñoz Yllera. A efectos de votación se hace constar que la Co- misión de Gobierno está integrada por diez miembros, incluido el Sr. Alcalde. Abierto el acto por la Presidencia se entra a conocer de los asuntos del orden del día para esta sesión. CONTRATACION PROPOSICION DEL CONCEJAL DELEGADO DE SERVICIOS DE LA CIUDAD SOBRE AMPLIACION DEL PLAZO DE EJECUCION DE LAS OBRAS INCLUI- DAS EN EL CONVENIO DE COLABORACION SUSCRITO CON IBERDROLA DISTRIBUCION ELECTRICA S.A.U. PARA EL ENTERRAMIENTO DE CEN- TROS DE TRANSFORMACION DE ALTA TENSION A LLEVAR A CABO DU- RANTE EL AÑO 2.003, AL AMPARO DEL ACUERDO ADOPTADO POR LA COMISION DE GOBIERNO DE 6 DE FEBRERO DE 2.003. -

02Lc Master 128-141

128 LCGC NORTH AMERICA VOLUME 20 NUMBER 2 FEBRUARY 2002 www.chromatographyonline.com Fifty Years of Gas Chromatography — The Pioneers I Knew, Part I MMilestonesilestones inin he First International Congress on longer among us. In the first three decades Chromatography Analytical Chemistry was held in of GC they were most active in the devel- T September 1952 in Oxford, United opment of the technique and its applica- Kingdom. The highlight of this meeting tions. They participated at the meetings, was a lecture on “Gas–Liquid Chromatog- lecturing on their newest results, and one raphy: a Technique for the Analysis of could not find any publication in which Volatile Materials,” by A.J.P. Martin (1). their work would not be quoted. They were Almost simultaneously, the seminal paper the true pioneers of GC. of A.T. James and A.J.P. Martin on the the- Rudolf Kaiser, one of the still-active pio- This column is the first of ory and practice of this technique (the neers, once said that chemists usually don’t a two-part “Milestones in manuscript of which was submitted on quote any paper that is more than seven Chromatography” series 5 June 1951) was published in Biochemical years old; this material belongs in the Journal (2), and within a few weeks it was archives and is no longer part of a “living dealing with the life and announced that Martin and R.L.M. Synge science.” In this two-part “Milestones in activities of key would receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry Chromatography” column, I want to chromatographers who “for the invention of partition chromatog- change this opinion. -

PETREAN NEWS AUTUMN 2013 by Giovanni Zappia

PETREAN NEWS AUTUMN 2013 By Giovanni Zappia Welcome to the autumn 2013 issue of Petrean News. We are delighted to announce that Professor Michael Levitt (matric. 1968) has been jointly awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize for Chemistry. He was elected to a Research Studentship in Molecular Biology in June 1968 and pursued his PhD research at Peterhouse before taking up a Research Fellowship at Gonville and Caius. Professor Chris Calladine (matric. 1953) remembers him well and reports that Sir John Kendrew (matric. 1947) thought highly of his work. This brings the number of Petreans who have been awarded this highest distinction in Chemistry to five: Archer Martin awarded in 1952; Max Perutz and John Kendrew awarded in 1962; Aaron Klug awarded in 1982; and now Michael Levitt – not bad for a small College! Anonymous On a less exalted note, we are also pleased to report that the Whittle Building is making good progress. Over the summer it has emerged from behind the hoardings in Gisborne Court and it is very exciting to see the building we have thought about for so long taking shape. There will be a garden party on 21 September next year to which all donors to the College’s Development Campaign will be invited to celebrate the completion of the Campaign and to see the new building. Giovanni Zappia Quentin Maile RECENT EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES Petrean Dinners 21 and 28 September 2013 This summer we hosted two Petrean Dinners, the first was on 21 September for members who matriculated between the years 1981 to 1985 and the second was held on 28 September for members who matriculated in the years 1976 to 1980.