Sequencing As a Way of Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vernon M. Ingram the WILLIAM ALLAN MEMORIAL AWARD Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics Toronto December 1, 1967

Vernon M. Ingram THE WILLIAM ALLAN MEMORIAL AWARD Presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics Toronto December 1, 1967 CITATION The contributions for which we honor Vernon Ingram represent a landmark in the history of molecular biology. Using an ingenious technique, he showed in 1956 that the difference between normal and sickle hemoglobin was caused by a single amino acid substitution. This work, followed by his demonstration of a similar mechanism for hemoglobin C and hemo- globin E, established clearly the nature of mutations in structural proteins and laid the groundwork for our concepts of gene action on the molecular level. 287 288 THE WILLIAM ALLAN MEMORIAL AWARD Vernon Ingram's investigations played a key role in the full integration of human genetics into the mainstream of modern genetic research. For the first time in the history of genetics, a phenomenon of fundamental significance for all forms of life was first demonstrated in man. Human genetics had come of age and became respectable to our more basically inclined colleagues. Vernon Ingram, as a scientist, represents a model for our students. Some investigators are analytical, while others are synthesizers and paint a broad sweep. Some are lone workers, others perform better in a team. Most biologists work in one field-within the framework of Ingram's interests, either as biochemists, as hematologists, as geneticists, or as evolutionists. Vernon Ingram has performed with versatility and distinction in all of these roles. As an analytical chemist, he developed the "fingerprinting" method of peptide separation, which he used to test theories of mutations. -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

RICHARD LAWRENCE MILLINGTON SYNGE BA, Phd(Cantab), Hondsc(Aberd), Hondsc(E.Anglia), Hon Dphil(Uppsala), FRS Nobel Laureate 1952

RICHARD LAWRENCE MILLINGTON SYNGE BA, PhD(Cantab), HonDSc(Aberd), HonDSc(E.Anglia), Hon DPhil(Uppsala), FRS Nobel Laureate 1952 R L M Synge was elected FRSE in 1963. He was born in West Kirby, Cheshire, on 28 October 1914, the son of Katherine (née Swan) and Lawrence Millington Synge, a Liverpool Stockbroker. The family was known to be living in Bridgenorth (Salop) in the early sixteenth century. At that time the name was Millington and there is a story that a member of the family from Millington Hall in Rostherne (Cheshire) sang so beautifully before King Henry VIII that he was told to take the name Synge. There have been various spellings of the name and in the nineteenth century the English branch settled on Sing which they retained until 1920 when both R M and L M Sing (Dick's uncle and father respectively) changed their names by deed poll to Synge. In the 19th and 20th centuries the Sing/Synge family played a considerable part in the life of Liverpool and Dick's father was High Sheriff of Cheshire in 1954. Dick was educated at Old Hall, a prep school in Wellington (Salop) and where he became renowned for his ability in Latin and Greek, subjects which he continued to study with such success at Winchester that in December 1931 when, just turned 17, he was awarded an Exhibition in Classics by Trinity College, Cambridge. His intention was to study science and Trinity allowed Dick to switch from classics to the Natural Sciences Tripos. To prepare for the change he returned to Winchester in January 1932 to study science for the next 18 months and was awarded the senior science prize for 1933. -

Perutz Letters

04_PerutzLet_1950_223-272.qxd:Layout 1 1/12/09 12:26 PM Page 261 Copyright 2009 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. Not for distribution. Do not copy without written permission from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. Selected Letters: 1950s 261 To Harold Himsworth, August 24, 1956 I am writing to tell you of exciting developments in the work of our unit. The first news is the discovery by Dr. Vernon Ingram of a definite chemi- cal difference between the globins of sickle cell anaemia and normal haemo- globin. Ingram has devised a new and rapid method of characterising proteins in considerable detail. This consists in first digesting the protein with trypsin and then spreading out the peptides of the digest on a two-dimensional chro- matogram, using electrophoresis in one direction and chromatography in the other. By applying this method to the two haemoglobins Ingram finds that all the 30 odd peptides in the digest are alike except for a single one. This peptide is uncharged in normal haemoglobin and carries a positive charge in haemo- globin S. The size of the peptide is probably of the order of 10 amino-acid residues. Ingram is now going to set about to determine the composition and sequence of the residues in the two peptides. This discovery is particularly interesting, Vernon Ingram in the because the change in structure from normal to early 1950s sickle cell haemoglobin is thought to be due to the action of one single gene, and the action of genes is thought to consist in determining the sequence of residues in a polypeptide chain. -

Anfinsen Experiments

Lecture Notes - 2 7.24/7.88J/5.48J The Protein Folding Problem Handouts: An Anfinsen paper Reading List Anfinsen Experiments The Problem of the title refers to how the amino acid sequence of a polypeptide chain determines the folded three-dimensional organization of the chain: • Does the sequence determine the structure?? • Protein Denaturation • Emergence of the Problem • Ribonuclease A • Refolding of ribonuclease in vitro. A. Protein Denaturation/Inactivation One of the features that identified proteins as distinctive polymers was 1) Unusual phase transition in semi purified proteins When exposed to relatively gentle conditions outside the range of physiological • heat • pH • salt • organic solvents, e.g. alcohols Lets consider the familiar transition I mentioned last week; • Heat denaturation; cooking the white of an egg • Acid denaturation; Milk turning sour Macroscopic changes in bulk solution; scatters visible light, increase in viscosity - white of egg: >>heat; opaque, hard; cool down; no change: Coagulation, Aggregation, precipitation, denaturation: One of the components is egg white lysozyme: activity assay; hydrolysis of bacterial cell walls: Activity remaining vs. temperature on same axes This transition: is Denaturation. These transitions were in general found to be irreversible: activity was not recovered upon cooling: Historically the study of the folding and unfolding of proteins emerged from trying to understand this unusual change of state or phase transitions. B. Emergence of the Protein Folding Problem In the period 1958-1960, the first structure of a protein molecule - myoglobin, the oxygen binding protein of muscle - was solved by John Kendrew in 1958, followed soon after by the related tetrameric red blood cell oxygen binding protein, hemoglobin, solved by Max Perutz, both of the British Medical Research Council Labs in Cambridge, U.K. -

DNA: the Timeline and Evidence of Discovery

1/19/2017 DNA: The Timeline and Evidence of Discovery Interactive Click and Learn (Ann Brokaw Rocky River High School) Introduction For almost a century, many scientists paved the way to the ultimate discovery of DNA and its double helix structure. Without the work of these pioneering scientists, Watson and Crick may never have made their ground-breaking double helix model, published in 1953. The knowledge of how genetic material is stored and copied in this molecule gave rise to a new way of looking at and manipulating biological processes, called molecular biology. The breakthrough changed the face of biology and our lives forever. Watch The Double Helix short film (approximately 15 minutes) – hyperlinked here. 1 1/19/2017 1865 The Garden Pea 1865 The Garden Pea In 1865, Gregor Mendel established the foundation of genetics by unraveling the basic principles of heredity, though his work would not be recognized as “revolutionary” until after his death. By studying the common garden pea plant, Mendel demonstrated the inheritance of “discrete units” and introduced the idea that the inheritance of these units from generation to generation follows particular patterns. These patterns are now referred to as the “Laws of Mendelian Inheritance.” 2 1/19/2017 1869 The Isolation of “Nuclein” 1869 Isolated Nuclein Friedrich Miescher, a Swiss researcher, noticed an unknown precipitate in his work with white blood cells. Upon isolating the material, he noted that it resisted protein-digesting enzymes. Why is it important that the material was not digested by the enzymes? Further work led him to the discovery that the substance contained carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and large amounts of phosphorus with no sulfur. -

Physics Today - February 2003

Physics Today - February 2003 Rosalind Franklin and the Double Helix Although she made essential contributions toward elucidating the structure of DNA, Rosalind Franklin is known to many only as seen through the distorting lens of James Watson's book, The Double Helix. by Lynne Osman Elkin - California State University, Hayward In 1962, James Watson, then at Harvard University, and Cambridge University's Francis Crick stood next to Maurice Wilkins from King's College, London, to receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their "discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material." Watson and Crick could not have proposed their celebrated structure for DNA as early in 1953 as they did without access to experimental results obtained by King's College scientist Rosalind Franklin. Franklin had died of cancer in 1958 at age 37, and so was ineligible to share the honor. Her conspicuous absence from the awards ceremony--the dramatic culmination of the struggle to determine the structure of DNA--probably contributed to the neglect, for several decades, of Franklin's role in the DNA story. She most likely never knew how significantly her data influenced Watson and Crick's proposal. Franklin was born 25 July 1920 to Muriel Waley Franklin and merchant banker Ellis Franklin, both members of educated and socially conscious Jewish families. They were a close immediate family, prone to lively discussion and vigorous debates at which the politically liberal, logical, and determined Rosalind excelled: She would even argue with her assertive, conservative father. Early in life, Rosalind manifested the creativity and drive characteristic of the Franklin women, and some of the Waley women, who were expected to focus their education, talents, and skills on political, educational, and charitable forms of community service. -

Peptide Chemistry up to Its Present State

Appendix In this Appendix biographical sketches are compiled of many scientists who have made notable contributions to the development of peptide chemistry up to its present state. We have tried to consider names mainly connected with important events during the earlier periods of peptide history, but could not include all authors mentioned in the text of this book. This is particularly true for the more recent decades when the number of peptide chemists and biologists increased to such an extent that their enumeration would have gone beyond the scope of this Appendix. 250 Appendix Plate 8. Emil Abderhalden (1877-1950), Photo Plate 9. S. Akabori Leopoldina, Halle J Plate 10. Ernst Bayer Plate 11. Karel Blaha (1926-1988) Appendix 251 Plate 12. Max Brenner Plate 13. Hans Brockmann (1903-1988) Plate 14. Victor Bruckner (1900- 1980) Plate 15. Pehr V. Edman (1916- 1977) 252 Appendix Plate 16. Lyman C. Craig (1906-1974) Plate 17. Vittorio Erspamer Plate 18. Joseph S. Fruton, Biochemist and Historian Appendix 253 Plate 19. Rolf Geiger (1923-1988) Plate 20. Wolfgang Konig Plate 21. Dorothy Hodgkins Plate. 22. Franz Hofmeister (1850-1922), (Fischer, biograph. Lexikon) 254 Appendix Plate 23. The picture shows the late Professor 1.E. Jorpes (r.j and Professor V. Mutt during their favorite pastime in the archipelago on the Baltic near Stockholm Plate 24. Ephraim Katchalski (Katzir) Plate 25. Abraham Patchornik Appendix 255 Plate 26. P.G. Katsoyannis Plate 27. George W. Kenner (1922-1978) Plate 28. Edger Lederer (1908- 1988) Plate 29. Hennann Leuchs (1879-1945) 256 Appendix Plate 30. Choh Hao Li (1913-1987) Plate 31. -

The Early Years-Across the Bench from Bruce (1963-1966)

The Early Years—Across the Bench From Bruce (1963–1966) The Early Years—Across the Bench From Bruce (1963–1966) Garland R. Marshall1,2 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, Center for Computational Biology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63110 2Department of Biomedical Engineering, Center for Computational Biology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63110 Received 14 July 2007; revised 20 September 2007; accepted 5 October 2007 Published online 16 October 2007 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI 10.1002/bip.20870 a Nobel Laureate, Chairman of the Department of Biology at ABSTRACT: Caltech and a member of the National Academy of Science, and was still willing to recommend me for graduate studies This personal reflection on the author’s experience as at Rockefeller. Bruce Merrifield’s first graduate student has been I was convinced at the time that I was chosen to study adapted from a talk given at the Merrifield Memorial neurophysiology, having failed miserably to isolate the acetyl- Symposium at the Rockefeller University on November choline receptor from denervated rabbit muscle as an under- graduate at Caltech. The outstanding neurophysiologists at 13, 2006. # 2007 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Biopolymers Rockefeller including H. Keffer Hartline, Nobel Laureate, (Pept Sci) 90: 190–199, 2008. were more interested, however, in the wiring diagrams of the Keywords: solid phase synthesis; Merrifield; DNA synthe- eye of the horseshoe crab2 than in how a small molecule sis; combinatorial chemistry could trigger the action potential. Thus, my first laboratory experience at Rockefeller was with Prof. Henry Kunkel, a This article was originally published online as an accepted prominent immunologist.3 Prof. -

Professor Michael Neuberger: Biochemist Behind Life-Saving

Professor Michael Neuberger: Biochemist behind life-saving ... http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/professor-mich... THE INDEPENDENT FRIDAY 08 NOVEMBER 2013 NEWS VOICES SPORT TECH LIFE PROPERTY ARTS + ENTS TRAVEL MONEY INDYBEST BLOGS UK World Business People Science Environment Media Technology Education Obituaries Diary 1 of 15 08/11/2013 10:36 Professor Michael Neuberger: Biochemist behind life-saving ... http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/professor-mich... News > Obituaries Professor Michael Neuberger: Biochemist behind life-saving work on the immune system He was seen as an outstanding mentor, with his sharp intellect and ability to get to the core issue Friday 01 November 2013 Shares: 28 PRINT A A A FOOD+DRINK Professor Michael Neuberger was pivotal to the ADS BY GOOGLE great advances in biomedical research, with his You Could Be Owed unravelling of the mysteries of human £2400 If You've Ever Had A Loan antibodies. A Fellow of Trinity College, You Could Be Owed A Cambridge where he was a director of studies in Refund Natural Sciences, he was also deputy director of LloydsTSB.BankRefunds.ne t Cambridge’s Medical Research Council FreeWatt Solar PV Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB). Biomass Lincs Renewable Energy With the demand for a new class of drugs to Matcha the day: Company of 2012. Heard about the fight diseases, such as cancer, as well as immune Commercial & Domestic soft drink set to be Systems disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, the the next big thing? www.freewatt.co.uk bio-tech industries have shown rapid growth. Buddhist monks Top10 Broadband in the Over 25 years, Neuberger made significant certainly have – they've UK been enjoying this Broadband From £2.50. -

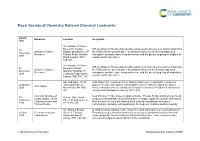

RSC Branding

Royal Society of Chemistry National Chemical Landmarks Award Honouree Location Inscription Date The Institute of Cancer Research, Chester ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Institute of Cancer Beatty Laboratories, 237 the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Research Fulham Road, Chelsea carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Road, London, SW3 ovarian and breast cancer. 6JB, UK The Institute of Cancer ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Research, Royal Institute of Cancer the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Marsden Hospital, 15 Research carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Cotswold Road, Sutton, ovarian and breast cancer. London, SM2 5NG, UK Ape and Apple, 28-30 John Dalton Street was opened in 1846 by Manchester Corporation in honour of 26 October John Dalton Street, famous chemist, John Dalton, who in Manchester in 1803 developed the Atomic John Dalton 2016 Manchester, M2 6HQ, Theory which became the foundation of modern chemistry. President of Manchester UK Literary and Philosophical Society 1816-1844. Chemical structure of Near this site in 1903, James Colquhoun Irvine, Thomas Purdie and their team found 30 College Gate, North simple sugars, James a way to understand the chemical structure of simple sugars like glucose and lactose. September Street, St Andrews, Fife, Colquhoun Irvine and Over the next 18 years this allowed them to lay the foundations of modern 2016 KY16 9AJ, UK Thomas Purdie carbohydrate chemistry, with implications for medicine, nutrition and biochemistry. -

Max Perutz (1914–2002)

PERSONAL NEWS NEWS Max Perutz (1914–2002) Max Perutz died on 6 February 2002. He Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1962 with structure is more relevant now than ever won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in his colleague and his first student John as we turn attention to the smallest 1962 after determining the molecular Kendrew for their work on the structure building blocks of life to make sense of structure of haemoglobin, the red protein of haemoglobin (Perutz) and myoglobin the human genome and mechanisms of in blood that carries oxygen from the (Kendrew). He was one of the greatest disease.’ lungs to the body tissues. Perutz attemp- ambassadors of science, scientific method Perutz described his work thus: ted to understand the riddle of life in the and philosophy. Apart from being a great ‘Between September 1936 and May 1937 structure of proteins and peptides. He scientist, he was a very kindly and Zwicky took 300 or more photographs in founded one of Britain’s most successful tolerant person who loved young people which he scanned between 5000 and research institutes, the Medical Research and was passionately committed towards 10,000 nebular images for new stars. Council Laboratory of Molecular Bio- societal problems, social justice and This led him to the discovery of one logy (LMB) in Cambridge. intellectual honesty. His passion was to supernova, revealing the final dramatic Max Perutz was born in Vienna in communicate science to the public and moment in the death of a star. Zwicky 1914. He came from a family of textile he continuously lectured to scientists could say, like Ferdinand in The Tempest manufacturers and went to the Theresium both young and old, in schools, colleges, when he had to hew wood: School, named after Empress Maria universities and research institutes.