20120620144528 1897.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Revised February 24, 2017 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. -

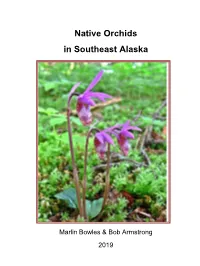

Native Orchids in Southeast Alaska

Native Orchids in Southeast Alaska Marlin Bowles & Bob Armstrong 2019 Preface Southeast Alaska's rainforests, peatlands and alpine habitats support a wide variety of plant life. The composition of this vegetation is strongly influenced by patterns of plant distribution and geographical factors. For example, the ranges of some Asian plant species extend into Southeast Alaska by way of the Aleutian Islands; other species extend northward into this region along the Pacific coast or southward from central Alaska. Included in Southeast Alaska's vegetation are at least 27 native orchid species and varieties whose collective ranges extend from Mexico north to beyond the Arctic Circle, and from North America to northern Europe and Asia. These orchids survive in a delicate ecological balance, requiring specific insect pollinators for seed production, and mycorrhizal fungi that provide nutrients essential for seedling growth and survival of adult plants. These complex relationships can lead to vulnerability to human impacts. Orchids also tend to transplant poorly and typically perish without their fungal partners. They are best left to survive as important components of biodiversity as well as resources for our enjoyment. Our goal is to provide a useful description of Southeast Alaska's native orchids for readers who share enthusiasm for the natural environment and desire to learn more about our native orchids. This book addresses each of the native orchids found in the area of Southeast Alaska extending from Yakutat and the Yukon border south to Ketchikan and the British Columbia border. For each species, we include a brief description of its distribution, habitat, size, mode of reproduction, and pollination biology. -

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

NOPES Newsletter 5 20

Newsletter of the Native Orchid Preservation and Education Society nativeorchidpreservationeducationsociety.com May 2020 Letter from the President Hello everyone, We were finally able to have an orchid hike. Ten of us met at Shawnee Backpacking Trail. Maintaining social distancing and wearing our masks, we were able to find Cypripedium acaule, the Pink Lady's-Slipper, Galearis spectabilis, the Showy Orchis blooming and Cypripedium parviflorum var. pubescens the Large Yellow Lady's-Slipper in bud. We will be organizing other hikes in the future and Jeanne is working on Zoom meetings for us. Check website for updates. Hope to see everyone soon! Galearis spectabilis, Teresa Huesman Showy Orchis, Shawnee State Forest In Bloom in May and June in Ohio and Kentucky Corallorhiza wisteriana Galearis spectabilis Cypripedium acaule Cypripedium kentuckiense Aplectrum hyemale Putty Cleistes bifaria Wister's Coral-Root Showy Orchid Pink Lady’s-Slipper Southern Lady’s Slipper Root Spreading Pogonia Cypripedium candidum Platanthera leucophaea Isotria verticillata Large Cypripedium parviflorum Pogonia ophioglossoides Neottia cordata Heart- Small White Lady’s- Eastern Prairie Fringed Whorled Pogonia var. pubescens Large Rose Pogonia Leaved Twayblade Slipper Orchid Yellow Lady’s-Slipper Liparis loeselii Platanthera lacera Liparis liliifolia Cypripedium reginae Spiranthes lucida Shining Calopogon tuberosus Loesel's Twayblade Ragged Fringed Orchid Large Twayblade Showy Lady’s-Slipper Ladies'-Tresses Grass Pink 1 Shawnee State Park Field Trip – May 2, 2020 - Jan Yates The more I’ve hiked Shawnee State Forest, the more it seems like we orchid enthusiasts have a code that would baffle many people. Mention to a colleague that you’re hiking Shawnee and they’ll ask ‘3 and 6?’ or ‘1 and 2?’ For other friends who are regular hikers/outdoors people/gardeners, I find myself explaining that these are the forest roads so rich in native orchids that you can virtually step out of the car and find them on the roadside. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Informação Base De Biodiversidade Da Ilha Do Corvo E Do Ilhéu De Vila Franca Do Campo

LIFE+ Safe Islands for Seabirds Relatório Acção A1 - Informação Base de Biodiversidade da Ilha do Corvo e do Ilhéu de Vila Franca do Campo LIFE07 NAT/P/000649 Corvo, Dezembro 2009 O P r o j e c O O projecto LIFE+ Safe Islands for Seabirds é uma parceria da SPEA com a Secretaria Regional do Ambiente e do Mar (SRAM), a Câmara Municipal do Corvo e a Royal Society for Protection of Birds, contando ainda com o apoio das seguintes entidades enquanto observadoras na sua Comissão Executiva: Direcção Regional dos Recursos Florestais (DRRF) e Câmara Municipal de Vila Franca do Campo. Trabalhar para o estudo e conservação das aves e seus habitats, promovendo um desenvolvimento que garanta a viabilidade do património natural para usufruto das gerações futuras. A SPEA – Sociedade Portuguesa para o Estudo das Aves é uma organização não governamental de ambiente que trabalha para a conservação das aves e dos seus habitats em Portugal. Como associação sem fins lucrativos, depende do apoio dos sócios e de diversas entidades para concretizar as suas acções. Faz parte de uma rede mundial de organizações de ambiente, a BirdLife International, que actua em mais de 100 países e tem como objectivo a preservação da diversidade biológica através da conservação das aves, dos seus habitats e da promoção do uso sustentável dos recursos naturais. LIFE+ Safe Islands for Seabirds. Relatório Inicial Sociedade Portuguesa para o Estudo das Aves, 2009 Direcção Nacional: Ricardo Azul Tomé, Maria Ana Peixe, Pedro Guerreiro, Ana Leal Martins, João Jara, Paulo Travassos, Pedro Coelho, Miguel Capelo, Paulo Simões Coelho, Teresa Catry Direcção Executiva: Luís Costa Coordenação do projecto: Pedro Luís Geraldes Equipa técnica: Ana Catarina Henriques, Carlos Silva, Joana Domingues, Nuno Oliveira, Sandra Hervías, Nuno Domingos, Susana Costa e Vanessa Oliveira. -

Jahresberichte Des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins In

Die Orchideen der Randgebiete des europäischen Florenbereiches Titelbild: Neottianthe cucullata (Foto: E. Klein) Die Orchideen der Randgebiete des europäischen Florenbereiches Redaktion: Karlheinz Senghas und Hans Sundermann Jahresberichte des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins Wuppertal Heft 29 - 1976 BRÜCKE-VERLAG KURT SCHMERSOW - HlLDESHElM Dieses Heft stellt den erweiterten Bericht über die „5.Wuppertaler Orchideen-Tagung" und damit die Fortsetzung von Heft 19 der Jahresberichte „Probleme der Orchideen- gattung Ophrys" (1964), von Heft 21/22 „Probleme der Orchideengattung Dactylorhiza" (1968), von Heft 23 „Probleme der Orchideengattung Epipactis" (1970) und von Heft 25 „Probleme der Orchideengattung Orchis, mit Nachträgen zu Ophrys, Dactylorhiza, Epipactis und Hybriden" (1972) dar. Das Heft erscheint gleichzeitig als Sonderheft der Zeitschrift „DIE ORCHIDEE", Herausgeber Deutsche Orchideen-Gesellschaft e. V. Ausgegeben arn 1. Dezember 1977. Naturwissenschaftlicher Verein Wuppertal und FUHLROTT-Museum Wuppertal Redaktions-Komitee: D. BRANDES (Mikroskopie), W. KOLBE (Zoologie unter Aus- schluß der Ornithologie), H. LEHMANN (Ornithologie), H. KNUBEL (Geographie), H. A. OFFE, M. LÜCKE (Geologie, Paläontologie und Mineralogie), H. SUNDERMANN (Botanik unter Ausschluß der Mykologie), H. WOLLWEBER (Mykologie) Schriftentausch und -vertrieb: FUHLROTT-Museum . Auer Schulstraße 20 .5600 Wuppertal 1 Satz und Druck: Hagemann-Druck, Hildesheim Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort (K. SENGHAS) .......................... Programm der 5 . Wuppertaler Orchideen-Tagung -

Phylogenetics of Tribe Orchideae (Orchidaceae: Orchidoideae)

Annals of Botany 110: 71–90, 2012 doi:10.1093/aob/mcs083, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org Phylogenetics of tribe Orchideae (Orchidaceae: Orchidoideae) based on combined DNA matrices: inferences regarding timing of diversification and evolution of pollination syndromes Luis A. Inda1,*, Manuel Pimentel2 and Mark W. Chase3 1Escuela Polite´cnica Superior de Huesca, Universidad de Zaragoza, carretera de Cuarte sn. 22071 Huesca, Spain, 2Facultade de Ciencias, Universidade da Corun˜a, Campus da Zapateira sn. 15071 A Corun˜a, Spain and 3Jodrell Laboratory, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3DS, UK * For correspondence. E-mail [email protected] Received: 3 November 2011 Returned for revision: 9 December 2011 Accepted: 1 March 2012 Published electronically: 25 April 2012 † Background and aims Tribe Orchideae (Orchidaceae: Orchidoideae) comprises around 62 mostly terrestrial genera, which are well represented in the Northern Temperate Zone and less frequently in tropical areas of both the Old and New Worlds. Phylogenetic relationships within this tribe have been studied previously using only nuclear ribosomal DNA (nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer, nrITS). However, different parts of the phylogenetic tree in these analyses were weakly supported, and integrating information from different plant genomes is clearly necessary in orchids, where reticulate evolution events are putatively common. The aims of this study were to: (1) obtain a well-supported and dated phylogenetic hypothesis for tribe Orchideae, (ii) assess appropriateness of recent nomenclatural changes in this tribe in the last decade, (3) detect possible examples of reticulate evolution and (4) analyse in a temporal context evolutionary trends for subtribe Orchidinae with special emphasis on pollination systems. -

Plantas Vasculares Endémicas Do Arquipélago Dos Açores

Plantas vasculares endémicas do Arquipélago dos Açores 1 In: Guia da Excursão Geobotânica: A paisagem vegetal da Ilha Terceira (Açores). Eds. Eduardo Dias, José Prieto, Carlos Aguiar, pp: 71-78. Universidade dos Açores, 2006. I. Plantas vasculares endémicas do Arquipélago dos Açores C. Aguiar, J.A. Fernández Prieto & E. Dias 1.1. Introdução Rivas-Martínez et al. (2002) propuseram a seguinte tipologia biogeográfica para o Arquipélago dos Açores: Reino Holártico, Região Eurossiberiana, Subregião Atlântico-Centroeuropeia, Província Atlântica Europeia, Subprovíncia Açoriana. Os mesmo autores conheceram sete sectores nesta subprovíncia, coincidentes com as seguintes ilhas ou grupos de ilhas: Santa Maria e Formigas, São Miguel, Terceira, Pico, Faial, São Jorge e Graciosa e Flores e Corvo. De acordo com a distribuição actual dos endemismos vasculares e as comunidade de plantas vasculares açorianos, que a seu tempo explicitaremos numa publicação dedicada, propomos a elevação da Subprovíncia Açoriana à categoria de Província – Província Açoriana – e a sua partição em três sectores: Sector Açoriano Oriental, Açoriano Central e Açoriano Ocidental. Neste Catálogo foi organizado com objectivo de clarificar a taxonomia, nomenclatura, corologia e comportamento fitossociológico dos endemismos vasculares açorianos. Uma lista deste género é o ponto de partia para a construção de uma tipologia biogeográfica informada, num ambiente insular. A distribuição à escala da ilha apresentada neste catálogo é baseada nos trabalhos de Hansen & Sunding (1993) e Schäfer (2003), com adições e correcções. Admitimos um total de 75 endemismos vasculares nos Açores, dos quais 47 % são hemicriptófitos. 1.2. Catálogo dos endemismos vasculares açorianos Agrostis azorica (Hochst.) Tutin & E. F. Warb. var. azorica , J. Bot. -

A Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of the Utrish Area (Russian Black Sea Coast) (Supplement to Alexey P

ALEXEY P. SEREGIN & ELENA G. SUSLOVA A checklist of the vascular plant flora of the Utrish area (Russian Black Sea Coast) (Supplement to Alexey P. Seregin & Elena G. Suslova. Contribution to the vascular plant flora of the Utrish area, a relic sub-Mediterranean ecosystems of the Russian Black Sea Coast). There are 848 numbered species in the checklist (in Corylus avellana and Ulmus minor two varieties are recognised). 173 species added and 50 were excluded in comparison with previously published data (Syomina & Suslova 2000; Seregin & Suslova 2002). Nomenclature of 69 species was corrected. Families and species are arranged alphabetically within each divisio (Pteridophyta, Equisetophyta, Pinophyta, Magnoliophyta). 5 species not collected since 1960 and probably extinct are listed without consequential numbers. Recent herbarium collections including personal collections by Seregin and Suslova are deposited in MWG. First list (Syomina & Suslova, 2000) was compiled on the basis of Grossheim’s guide (1949) with nomenclatural verification of names according Czerepanov (1995). Nomenclature in addition (Seregin & Suslova, 2002) was checked after Zernov (2000). His later guide (Zernov, 2002) is a nomenclatural basis of the present checklist, though there are some deviations. We are citing 4 sources in brief nomenclatural references to link our papers (Syomina & Suslova 2000; Seregin & Suslova 2002) and standard guides (Grossheim 1949; Zernov 2002). 43 species listed in the Russian Red Data Book are marked with RUS, and 6 species protected on regional level (listed in the Red Data Book of Krasnodarsky Kray) are marked with REG. These marks are used before the name accepted in the Red Data Books. PTERIDOPHYTA Aspleniaceae 1. -

Circumscribing Genera in the European Orchid Flora: a Subjective

Ber. Arbeitskrs. Heim. Orchid. Beiheft 8; 2012: 94 - 126 Circumscribing genera in the European orchid lora: a subjective critique of recent contributions Richard M. BATEMAN Keywords: Anacamptis, Androrchis, classiication, evolutionary tree, genus circumscription, monophyly, orchid, Orchidinae, Orchis, phylogeny, taxonomy. Zusammenfassung/Summary: BATEMAN , R. M. (2012): Circumscribing genera in the European orchid lora: a subjective critique of recent contributions. – Ber. Arbeitskrs. Heim. Orch. Beiheft 8; 2012: 94 - 126. Die Abgrenzung von Gattungen oder anderen höheren Taxa erfolgt nach modernen Ansätzen weitestgehend auf der Rekonstruktion der Stammesgeschichte (Stamm- baum-Theorie), mit Hilfe von großen Daten-Matrizen. Wenngleich aufgrund des Fortschritts in der DNS-Sequenzierungstechnik immer mehr Merkmale in der DNS identiiziert werden, ist es mindestens genauso wichtig, die Anzahl der analysierten Planzen zu erhöhen, um genaue Zuordnungen zu erschließen. Die größere Vielfalt mathematischer Methoden zur Erstellung von Stammbäumen führt nicht gleichzeitig zu verbesserten Methoden zur Beurteilung der Stabilität der Zweige innerhalb der Stammbäume. Ein weiterer kontraproduktiver Trend ist die wachsende Tendenz, diverse Datengruppen mit einzelnen Matrizen zu verquicken, die besser einzeln analysiert würden, um festzustellen, ob sie ähnliche Schlussfolgerungen bezüglich der Verwandtschaftsverhältnisse liefern. Ein Stammbaum zur Abgrenzung höherer Taxa muss nicht so robust sein, wie ein Stammbaum, aus dem man Details des Evo- lutionsmusters -

Phytogeographical Analysis and Ecological Factors of the Distribution of Orchidaceae Taxa in the Western Carpathians (Local Study)

plants Article Phytogeographical Analysis and Ecological Factors of the Distribution of Orchidaceae Taxa in the Western Carpathians (Local study) Lukáš Wittlinger and Lucia Petrikoviˇcová * Department of Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, 94974 Nitra, Slovakia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +421-907-3441-04 Abstract: In the years 2018–2020, we carried out large-scale mapping in the Western Carpathians with a focus on determining the biodiversity of taxa of the family Orchidaceae using field biogeographical research. We evaluated the research using phytogeographic analysis with an emphasis on selected ecological environmental factors (substrate: ecological land unit value, soil reaction (pH), terrain: slope (◦), flow and hydrogeological productivity (m2.s−1) and average annual amounts of global radiation (kWh.m–2). A total of 19 species were found in the area, of which the majority were Cephalenthera longifolia, Cephalenthera damasonium and Anacamptis morio. Rare findings included Epipactis muelleri, Epipactis leptochila and Limodorum abortivum. We determined the ecological demands of the abiotic environment of individual species by means of a functional analysis of communities. The research confirmed that most of the orchids that were studied occurred in acidified, calcified and basophil locations. From the location of the distribution of individual populations, it is clear that they are generally arranged compactly and occasionally scattered, which results in ecological and environmental diversity. During the research, we identified 129 localities with the occurrence of Citation: Wittlinger, L.; Petrikoviˇcová, L. Phytogeographical Analysis and 19 species and subspecies of orchids. We identify the main factors that threaten them and propose Ecological Factors of the Distribution specific measures to protect vulnerable populations.