Dam Complex of Upper Atbara Project Socio-Economic Assessment Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sudan, Performed by the Much Loved Singer Mohamed Wardi

Confluence: 1. the junction of two rivers, especially rivers of approximately equal width; 2. an act or process of merging. Oxford English Dictionary For you oh noble grief For you oh sweet dream For you oh homeland For you oh Nile For you oh night Oh good and beautiful one Oh my charming country (…) Oh Nubian face, Oh Arabic word, Oh Black African tattoo Oh My Charming Country (Ya Baladi Ya Habbob), a poem by Sidahmed Alhardallou written in 1972, which has become one of the most popular songs of Sudan, performed by the much loved singer Mohamed Wardi. It speaks of Sudan as one land, praising the country’s diversity. EQUAL RIGHTS TRUST IN PARTNERSHIP WITH SUDANESE ORGANISATION FOR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT In Search of Confluence Addressing Discrimination and Inequality in Sudan The Equal Rights Trust Country Report Series: 4 London, October 2014 The Equal Rights Trust is an independent international organisation whose pur- pose is to combat discrimination and promote equality as a fundamental human right and a basic principle of social justice. © October 2014 Equal Rights Trust © Photos: Anwar Awad Ali Elsamani © Cover October 2014 Dafina Gueorguieva Layout: Istvan Fenyvesi PrintedDesign: in Dafinathe UK Gueorguieva by Stroma Ltd ISBN: 978-0-9573458-0-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by other means without the prior written permission of the publisher, or a licence for restricted copying from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd., UK, or the Copyright Clearance Centre, USA. -

2017. Blin and Arab Historians in the Twelfth Century

BLIN AND ARAB HISTORIANS IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY. Presented on the Blin Conference Stuttgart, Germany in July 21-23, 2017. Idris Abubeker (PhD) Abstract The ancient history of the Blin still needs to be investigated. Within this premise, this paper discusses three Arabic texts written in the twelfth century in relation to the history of the Blin. Two of them were written by El-Idrissi the historian while the third one was a manuscript written by a poet called Ibn al-Qalaqis. I would argue that one of the texts of El- Idrissi and the manuscript of Ibn al-Qalaqis are discussed for the first time. Giving prominence for treatment of the two texts, may contribute to our knowledge of the study of Blin. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The first inhabitant of the east Africa region is the Nilotic group. They dominated this region for thousands of years, until the advent of the Cushitic group that led them either to mix with them or to migrate out of that area or to settle in specific areas1. It is believed that the Cushitic group entered to this region from the Arabian Peninsula via Bab al-Mandab or from the Caucasus through Egypt between the fifth and third millennium BC. They relied on animals that could live in harsh desert life like camels and others. They developed architecture and music, as evidenced by the construction of pyramids in Egypt and the Church of Lalibela in Ethiopia and the ancient port of Adulis in Eritrea and others2. The demographics of these groups were spread throughout the region from southern Egypt to northern Kenya. -

The Beja Language Today in Sudan: the State of the Art in Linguistics Martine Vanhove

The Beja Language Today in Sudan: The State of the Art in Linguistics Martine Vanhove To cite this version: Martine Vanhove. The Beja Language Today in Sudan: The State of the Art in Linguistics. Proceed- ings of the 7th International Sudan Studies Conference April 6th - 8th 2006. Bergen, Norway, 2006, Bergen, Norway. pp.CD Rom. halshs-00010091 HAL Id: halshs-00010091 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00010091 Submitted on 10 Apr 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 2006. Proceedings of the 7th International Sudan Studies Conference April 6th – 8th 2006. Bergen, Norway. CD Rom, Bergen: University of Bergen. THE BEJA LANGUAGE TODAY IN SUDAN: THE STATE OF THE ART IN LINGUISTICS MARTINE VANHOVE (LLACAN, UMR 8135 - CNRS, INALCO) 1 INTRODUCTION The Beja language is spoken in the eastern part of the Sudan by some 1,100,000 Muslim people, according to the 1998 census. It belongs to the Cushitic family of the Afro-Asiatic genetic stock. It is the sole member of its northern branch, and is so different from other Cushitic languages in many respects and especially as regards to the lexicon, that the American linguist, Robert Hetzron (1980), thought it best to set it apart from Cushitic as an independent branch of Afro-Asiatic. -

Tekna Berbers in Morocco

www.globalprayerdigest.org GlobalDecember 2019 • Frontier Ventures •Prayer 38:12 Digest The Birth Place of Christ, But Few Will Celebrate His Birth 4—North Africa: Where the Berber and Arab Worlds Blend 7—The Fall of a Dictator Spells a Rise of Violence 22—Urdus: A People Group that is Not a People Group 23—You Can Take the Bedouin Out of the Desert, but … December 2019 Editorial EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Feature of the Month Keith Carey For comments on content call 626-398-2241 or email [email protected] ASSISTANT EDITOR Dear Praying Friends, Paula Fern Pray For Merry Christmas! WRITERS Patricia Depew Karen Hightower This month we will pray for the large, highly unreached Wesley Kawato A Disciple-Making Movement Among Ben Klett Frontier People Groups (FPGs) in the Middle East. They David Kugel will be celebrating Christmas in Bethlehem, and a few other Christopher Lane Every Frontier People Group in the Ted Proffitt places where Arabs live, but most will treat December 25 Cory Raynham like any other day. It seems ironic that in the land of Christ’s Lydia Reynolds Middle East Jean Smith birth, his birth is only celebrated by a few. Allan Starling Chun Mei Wilson Almost all the others are Sunni Muslim, but that is only a John Ytreus part of the story. Kurds and Berbers are trying to maintain PRAYING THE SCRIPTURES their identity among the dominant Arabs, while Bedouin Keith Carey tribes live their lives much like Abraham did thousands of CUSTOMER SERVICE years ago. Who will take Christ to these people? Few if any Lois Carey Lauri Rosema have tried it to this day. -

Beja Terms Used: Silif: Customary Law That Regulates All Beja Groups Diwab: Linage

Beja terms used: Silif: customary law that regulates all Beja groups Diwab: linage 1. Description 1.1 Name(s) of society, language, and language family: Name of society: Beja, Bedawi (2) Language: Bedawiyet (1) Language Family: Cushitic (1) 1.2 ISO code (3 letter code from ethnologue.com): bej (1) 1.3 Location (latitude/longitude): Red Sea, Kassaia States, Southeast River Nile, Egypt, Eritrea (1) 1.4 Brief history: “The Beja are traditionally nomadic shepherds who migrate annually with their herds. In the north, small groups of nomads herd flocks of sheep, goats, camels, and cattle” (2). They live scattered across the desert regions of Sudan, Egypt and Eritrea (2). The Beja are native Africans who have lived in their current homelands for more than 4,000 years, and (in Sudan) are divided into four tribes: the Hadendowa, the Amarar, the Abadba, and the Beni Amer (2). The Beja are traditionally nomadic, so they live in portable tents that are curved in shape and are made from woven palm fronds (2). 1.5 Influence of missionaries/schools/governments/powerful neighbors: The Beja have never been conquered by a foreign power (2). 1.6 Ecology (natural environment): Ecosystem type: Savanna (6) Geological type: Riverine and Plains (6) 1.7 Population size, mean village size, home range size, density: Beja live in clans, and are named after their ancestors. Clans vary from one to twelve families has it’s own pastures and water sites that others may use, but with permission. The Beja always show kindness to other clans, but are not necessarily friendly to foreigners (2). -

The Islamization of the Beja Until the 19 Century Abstract

Beiträge zur 1. Kölner Afrikawissenschaftlichen Nachwuchstagung (KANT I) Herausgegeben von Marc Seifert, Markus Egert, Fabian Heerbaart, Kathrin Kolossa, Mareike Limanski, Meikal Mumin, Peter André Rodekuhr, Susanne Rous, Sylvia Stankowski und Marilena Thanassoula The Islamization of the Beja until the 19th century Jan Záhořík, Department of Anthropology, University of West Bohemia, Pilsen Abstract The Beja tribes belong to the oldest known nations not only in the Sudan but also in the whole Africa. Their history goes back to the antiquity and nowadays they inhabit the eastern parts of the Islamic Republic of Sudan, the northern triangle of Eritrea, the Ababda tribe lives in the southern parts of Egypt around Assuan, and small enclaves of the Beja can be found in the northern tip of Ethiopia. In this paper I will try to show the process of Islamization of these Cushitic people and to reinterpret as well as to present less known or insufficiently accented facts. There are several uncertainties that require attention. First of all, the date of the beginning of Islamization differs according to several scholars and authors. Second, it is difficult to find some adequate conclusions of the early Islamization of the Beja while we know almost nothing about the extent of this process in the 9th and 10th centuries. Even though we have some direct sources from Arab scholars such as Ibn Battuta, al-Mas’udi, Ibn Jubair and some others, the information about Islam among the Beja differ, so we have no clear idea of the early Islamization of the Beja tribes. In my opinion, we cannot consider the conversion to Islam a quick, but rather a gradual process caused by the intrusion of the Arab tribes since the 9th century and by the increasing importance of the Beja camel guiders and caravan route leaders. -

Sudan Country Report

SUDAN COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Sudan April 2004 CONTENTS 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.7 2. GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.3 3. ECONOMY 3.1 - 3.2 4. HISTORY 1989 - April 2004: The al-Bashir Regime 4.1 - 4.3 Events of 2002 - 2004 4.4 - 4.19 5. STATE STRUCTURES The Constitution 5.1 - 5.2 The Political System 5.3 - 5.5 Political Parties 5.6 - 5.7 The Judiciary 5.8 - 5.17 Military Service and the Popular Defence Force 5.18 - 5.26 Conscription 5.27 - 5.32 Exemptions, Pardons and Postponements 5.33 - 5.36 Internal Security 5.37 - 5.38 Legal Rights/Detention 5.39 - 5.43 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.44 - 5.47 Medical Services 5.48 - 5.55 HIV/AIDS 5.56 - 5.60 Mental Health Care 5.61 - 5.62 The Education System 5.63 - 5.64 Sudanese Nationality Laws 5.65 - 5.68 6. HUMAN RIGHTS 6.A. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES Overview 6.1 - 6.12 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.13 - 6.17 Newspapers 6.18 - 6.21 Television, Radio and the Internet 6.22 - 6.24 Freedom of Religion 6.25 - 6.37 Forced Religious Conversion 6.38 - 6.39 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.40 - 6.46 Meetings and Demonstrations 6.47 - 6.49 Employment Rights 6.50 - 6.52 Trade Unions 6.53 - 6.58 Wages and Conditions 6.59 - 6.62 People Trafficking 6.63 - 6.66 Slavery 6.67 - 6.71 Freedom of Movement 6.72 - 6.75 Passports 6.76 - 6.77 Exit Visas 6.78 - 6.81 Airport Security 6.82 - 6.83 Returning Sudanese Nationals 6.84 - 6.87 Arbitrary Interference with Privacy 6.88 - 6.91 6.B. -

Development Deferred: Eastern Sudan After the ESPA

36 Development Deferred: Eastern Sudan after the ESPA By the Small Arms Survey Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in May 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-10-1 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 36 Contents List of maps, tables, and figures ................................................................................................................................................ 4 List of abbreviations .................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Sudan: Preserving Peace in the East

Sudan: Preserving Peace in the East Africa Report N°209 | 26 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... ii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Road to the Eastern Sudan Peace Agreement ........................................................... 2 A. Sudan’s Forgotten East: People and Politics ............................................................. 2 B. The Beja Congress ...................................................................................................... 3 C. The Eastern Front’s Emergence ................................................................................ 4 1. The National Democratic Alliance’s collapse ....................................................... 4 2. Forging the Eastern Front (EF) ............................................................................ 5 D. Signing the ESPA ....................................................................................................... 6 1. NCP calculations ................................................................................................. -

07-01-12 Beja.Indd

Institute for Security Studies Situation Report Date Issued: 12 January 2007 Author: Mariam Bibi Jooma1 Distribution: General Contact: [email protected] Looking East: The politics of peacemaking in the Beja region of Sudan At the end of 2006, and even as the conflict in Sudan’s western region of Darfur intensified once more, another area of instability came under the spotlight – much-neglected eastern Sudan. While the term “marginalised” has often been applied to southern Sudan and latterly Darfur, reflecting their alienation from the centre of national affairs, development and services, it is especially relevant in the case of the Beja region of eastern Sudan. This brings into question not only the effectiveness and viability of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement reached between Khartoum and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement in the South as a means to address broader Sudanese issues, but the very mechanisms of Sudanese diplomacy and the ability to challenge rather than reinforce the principal ‘entrepreneurs of violence’. On 16 October 2006, the Government of Sudan signed yet another peace agreement, the third in the space of two years. In effect this meant that three regions of the Sudan – south, west and east – under separate conditions, have entered into power sharing, wealth sharing and security arrangements with the governing National Congress Party (NCP) based in Khartoum. Although, superficially, this might be seen to herald the transformation of the Sudanese political landscape on an incremental basis, in fact it has narrowed the political arena by reinforcing the primacy of the ruling party as the key partner in each of the peace agreements, allowing the NCP to bypass the nationwide development of accountable oppositional politics. -

Conflict of National Identity in Sudan

CONFLICT OF NATIONAL IDENTITY IN SUDAN Kuel Maluil Jok Academic Dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki, in auditorium XII, on 31 March 2012 at 10 o‟clock. University of Helsinki, Department of World Cultures Kuel Jok Conflict of National Identity in Sudan Copyright © Kuel Jok 2012 ISBN 978-952-10-7919-1 (Print) ISBN 978-952-10-7891-0 (PDF) UNIGRAFIA Helsinki University Print Helsinki 2012 ii ABSTRACT This study addresses the contemporary conflict of national identity in Sudan between the adherents of „Islamic nationalism‟ and „customary secularism‟. The former urge the adoption of a national constitution that derives its civil and criminal laws from Sharia (Islamic law) and Arabic be the language of instruction in national institutions of Sudan. The group argues that the intertwined model of the Islamic-Arab cultural identity accelerates assimilation of the heterogeneous African ethnic and religious diversities in Sudan into a homogeneous national identity defining Sudan as an Islamic-Arab state. The latter demand the adoption of secular laws, which must be derived from the diverse set of customary laws and equal opportunities for all African languages beside Arabic and English. The group claims that the adoption of the Islamic laws and Arabic legalises the treatment of the citizens in the country in terms of religion and race and that implies racism and discrimination. In this way, the adherents of the Islamic nationalism imposed the Islamic-Arab model. In reaction, the Muslims and the non-Muslim secularists resort to violence as an alternative model of resistance. -

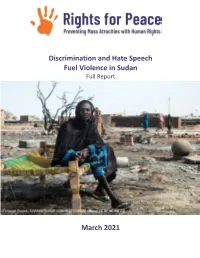

Discrimination and Hate Speech Fuel Violence in Sudan Full Report

Discrimination and Hate Speech Fuel Violence in Sudan Full Report March 2021 Rights for Peace is a non-profit that seeks to prevent mass atrocity crimes in fragile States by collaborating with local organisations. We undertake training, research and advocacy, addressing the drivers of violence, particularly hate-based ideology. This project was funded by KAICIID International Dialogue Centre. The content of this paper does not necessarily reflect the views of the donor. Rights for Peace 41 Whitcomb Street London WC2H 7DT United Kingdom UK Registered Charity No. 1192434 To find out more, get involved in our work or donate, please visit: www.rightsforpeace.org Follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn and Facebook 2 Table of Contents EXAMPLES OF REPORTED HATE SPEECH 4 INTRODUCTION 5 METHODOLOGY AND DISCLAIMER 7 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS 8 MAP OF SUDAN 10 PART I - CONTEXT OF DISCRIMINATION IN SUDAN 11 1. HISTORIC DISCRIMINATION AND VIOLENCE 11 1.2 TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY 12 1.3 ESCALATING HATE-BASED VIOLENCE IN THE REGIONS 13 2. ESCALATING HATE SPEECH AND CONFLICT IN EASTERN SUDAN 15 2.1 NEGLECT AND DIVISIONS IN EASTERN SUDAN 15 2.2 CLASHES BETWEEN THE HADENDAWA AND BENI AMER IN KASSALA (2020) 16 2.3 EXTREME DIVISIONS AND VIOLENCE IN PORT SUDAN (2019) 20 2.4 DEADLY CLASHES IN AL-GADARIF (2020) 21 2.5 KILLINGS AND REPRISALS INVOLVING ‘KANABI’ (CAMP) RESIDENTS (2020) 21 3. HATE SPEECH AND CONFLICT IN DARFUR 23 3.1 INCITEMENT TO GENOCIDE IN DARFUR (2005 TO 2020): 25 3.2 ONGOING VIOLENCE IN WEST DARFUR (2020-21) 26 3.3 A WIDER PATTERN OF ESCALATING VIOLENCE IN DARFUR 28 3.4 RECENT EFFORTS TO RESTORE SECURITY IN WEST DARFUR 29 4.