Discrimination and Hate Speech Fuel Violence in Sudan Full Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darfur Genocide

Darfur genocide Berkeley Model United Nations Welcome Letter Hi everyone! Welcome to the Darfur Historical Crisis committee. My name is Laura Nguyen and I will be your head chair for BMUN 69. This committee will take place from roughly 2006 to 2010. Although we will all be in the same physical chamber, you can imagine that committee is an amalgamation of peace conferences, UN meetings, private Janjaweed or SLM meetings, etc. with the goal of preventing the Darfur Genocide and ending the War in Darfur. To be honest, I was initially wary of choosing the genocide in Darfur as this committee’s topic; people in Darfur. I also understood that in order for this to be educationally stimulating for you all, some characters who committed atrocious war crimes had to be included in debate. That being said, I chose to move on with this topic because I trust you are all responsible and intelligent, and that you will treat Darfur with respect. The War in Darfur and the ensuing genocide are grim reminders of the violence that is easily born from intolerance. Equally regrettable are the in Africa and the Middle East are woefully inadequate for what Darfur truly needs. I hope that understanding those failures and engaging with the ways we could’ve avoided them helps you all grow and become better leaders and thinkers. My best advice for you is to get familiar with the historical processes by which ethnic brave, be creative, and have fun! A little bit about me (she/her) — I’m currently a third-year at Cal majoring in Sociology and minoring in Data Science. -

Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 Highlights

Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 UNICEF and partners assess damage to communities in southern Khartoum. Sudan was significantly affected by heavy flooding this summer, destroying many homes and displacing families. @RESPECTMEDIA PlPl Reporting Period: July-September 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers • Flash floods in several states and heavy rains in upriver countries caused the White and Blue Nile rivers to overflow, damaging households and in- 5.39 million frastructure. Almost 850,000 people have been directly affected and children in need of could be multiplied ten-fold as water and mosquito borne diseases devel- humanitarian assistance op as flood waters recede. 9.3 million • All educational institutions have remained closed since March due to people in need COVID-19 and term realignments and are now due to open again on the 22 November. 1 million • Peace talks between the Government of Sudan and the Sudan Revolu- internally displaced children tionary Front concluded following an agreement in Juba signed on 3 Oc- tober. This has consolidated humanitarian access to the majority of the 1.8 million Jebel Mara region at the heart of Darfur. internally displaced people 379,355 South Sudanese child refugees 729,530 South Sudanese refugees (Sudan HNO 2020) UNICEF Appeal 2020 US $147.1 million Funding Status (in US$) Funds Fundi received, ng $60M gap, $70M Carry- forward, $17M *This table shows % progress towards key targets as well as % funding available for each sector. Funding available includes funds received in the current year and carry-over from the previous year. 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF’s 2020 Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) appeal for Sudan requires US$147.11 million to address the new and protracted needs of the afflicted population. -

11 May 2020 TRIAL CHAMBER IV Before: Judge K

ICC-02/05-03/09-673-Red 11-05-2020 1/18 EK T Original: English No.: ICC-02/05-03/09 Date: 11 May 2020 TRIAL CHAMBER IV Before: Judge Kimberly Prost, Presiding Judge Judge Robert Fremr Judge Reine Alapini-Gansou SITUATION IN DARFUR, THE SUDAN IN THE CASE OF THE PROSECUTOR v. ABDALLAH BANDA ABAKAER NOURAIN Public Public redacted version of “Prosecution’s submissions on trials in absentia in light of the specific circumstances of the Banda case”, 13 December 2019, ICC-02/05-03/09-673-Conf- Exp Source: Office of the Prosecutor No. ICC-02/05-03/09 1/18 11 May 2020 ICC-02/05-03/09-673-Red 11-05-2020 2/18 EK T Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence of Mr Banda Ms Fatou Bensouda Mr Charles Achaleke Taku Mr James Stewart Mr Julian Nicholls Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Ms Hélène Cissé Mr Jens Dieckmann Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for Victims The Office of Public Counsel for the Defence States Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Counsel Support Section Mr Peter Lewis Dr Esteban Peralta Losilla Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Victims Participation and Reparations Other Section No. ICC-02/05-03/09 2/18 11 May 2020 ICC-02/05-03/09-673-Red 11-05-2020 3/18 EK T I. INTRODUCTION 1. On 13 November 2019, in the “Order following Status Conference on 30 October 2019,”1 Trial Chamber IV (“Trial Chamber” or “Chamber”), by majority, invited the Defence and the Prosecution “to make submissions on trials in absentia in light of the specific circumstances of this case by 13 December 2019.”2 2. -

Nomads' Settlement in Sudan: Experiences, Lessons and Future Action

Nomads’ Settlement in Sudan: Experiences, Lessons and Future action (STUDY 1) Copyright © 2006 By the United Nations Development Programme in Sudan House 7, Block 5, Avenue P.O. Box: 913 Khartoum, Sudan. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retreival system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission. Printed by SCPP Editor: Ms: Angela Stephen Available through: United Nations Development Programme in Sudan House 7, Block 5, Avenue P.O. Box: 913 Khartoum, Sudan. www.sd.undp.org The analysis and policy recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations, including UNDP, its Executive Board or Member States. This study is the work of an independent team of authors sponsored by the Reduction of Resource Based Conflcit Project, which is supported by the United Nations Development Programme and partners. Contributing Authors The Core Team of researchers for this report comprised of: 1. Professor Mohamed Osman El Sammani, Former Professor of Geography, University of Khartoum, Team leader, Principal Investigator, and acted as the Report Task Coordinator. 2. Dr. Ali Abdel Aziz Salih, Ph.D. in Agricultural Economics, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Khartoum. Preface Competition over natural resources, especially land, has become an issue of major concern and cause of conflict among the pastoral and farming populations of the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. Sudan, where pastoralists still constitute more than 20 percent of the population, is no exception. Raids and skirmishes among pastoral communities in rural Sudan have escalated over the recent years. -

Periodic Report January 2014

منظمة حقوق اﻻنسان والتنمية Human Rights and Development Organization (HUDO) South Kordufan / Nuba Mountains Monthly Report (January 2014) Introduction: In this month Sudan government become very much repressive by reinforcing all rejected Laws, for the first time it has reinforced the Armed Forces Law amended in June last year, this laws allows prosecution of civilians before military courts. It has also activated other laws of the Voluntary Work Act for the year 2006 which gives the Minister the right to do whatever suits him. Under these laws the minister suspended the activities of the International Committee of Red Cross (ICRC), this move band more than 1.5 million people from the service of ICRC mostly in Darfur. Despite the crimes they committed in Darfur and their participation in the fighting in Southern Kordofan recently, the Janjaweed militias are now terrorizing civilians in Al Obeid before those who created them in Darfur and brought them to Kordofan. Security Situation: Sudanese authority continues air bombardment in the Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile, Kauda area (SPLA control) has been aggressively bombarded during January this year. The security situation is worsening in Kordofan Al Obeid due to the presence of the Janjaweed after being chased from battle field in Southern Kordofan. Currently they are rapping women, looting civilians’ properties and attacking people on daily bases in Al Obeid. Political Development: The President’s recent statement which people had been optimistically awaiting for was very disappointing; it was expected to bring new changes in Sudanese politics but was sarcasm instead. Peace talks between Sudan Government and SPLM- N is due to resume in February with a hope of pushing the implementation of the previous agreements and opening the paths for relief to reach the war affected people in Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile pending for the final and comprehensive settlement of the conflict. -

“Kankasha” in Kassala: a Prospective Observational Cohort Study of the Clinical Characteristics, Epidemiology, Genetic Origi

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.23.20199976; this version posted September 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 1 1 Title [216/250 characters] 2 “Kankasha” in Kassala: a prospective observational cohort study of the clinical characteristics, 3 epidemiology, genetic origin, and chronic impact of the 2018 epidemic of Chikungunya virus 4 infection in Kassala, Sudan 5 Short title: [66/70characters] 6 Understanding the 2018 Chikungunya virus epidemic in Eastern Sudan 7 8 Authors: Hilary Bower1*, Mubarak el Karsany2,3*, Abd Alhadi Adam Hussein4, Mubarak Ibrahim 9 Idriss5, Ma’aaza Abasher AlZain6, Mohamed Elamin Ahmed Alfakiyousif2, Rehab Mohamed2, Iman 10 Mahmoud2, Omer Albadri,7 Suha Abdulaziz Alnour Mahmoud10, Orwa Ibrahim Abdalla10, Mawahib 11 Eldigail2, Nuha Elagib2, Ulrike Arnold1, Bernardo Gutierrez8, Oliver G. Pybus8, Daniel P. Carter9, Steven 12 T. Pullan9, Shevin T. Jacob11, Tajeldin Mohammedein Abdallah4,10#, Benedict Gannon1# , Tom E. 13 Fletcher11# 14 * Equal first authors, # Equal senior authors 15 16 Authors’ affiliations 17 1. UK Public Health Rapid Support Team, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine/Public Health 18 England, London, United Kingdom 19 2. National Public Health Laboratory, Federal Ministry of Health, Khartoum, Sudan 20 3. Karary University, Omdurman, Sudan 21 4. University of Kassala, Kassala, Sudan 22 5. Laboratory Division, Kassala State Ministry of Health, Kassala, Sudan 23 6. Communicable Disease Surveillance & Events Unit, Federal Ministry of Health, Khartoum, Sudan 24 7. -

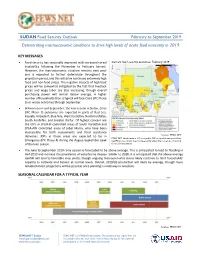

Sudan Food Security Outlook Report

SUDAN Food Security Outlook February to September 2019 Deteriorating macroeconomic conditions to drive high levels of acute food insecurity in 2019 KEY MESSAGES • Food security has seasonally improved with increased cereal Current food security outcomes, February 2019 availability following the November to February harvest. However, the macroeconomic situation remains very poor and is expected to further deteriorate throughout the projection period, and this will drive continued extremely high food and non-food prices. The negative impacts of high food prices will be somewhat mitigated by the fact that livestock prices and wage labor are also increasing, though overall purchasing power will remain below average. A higher number of households than is typical will face Crisis (IPC Phase 3) or worse outcomes through September. • Between June and September, the lean season in Sudan, Crisis (IPC Phase 3) outcomes are expected in parts of Red Sea, Kassala, Al Gadarif, Blue Nile, West Kordofan, North Kordofan, South Kordofan, and Greater Darfur. Of highest concern are the IDPs in SPLM-N controlled areas of South Kordofan and SPLA-AW controlled areas of Jebel Marra, who have been inaccessible for both assessments and food assistance deliveries. IDPs in these areas are expected to be in Source: FEWS NET FEWS NET classification is IPC-compatible. IPC-compatible analysis follows Emergency (IPC Phase 4) during the August-September peak key IPC protocols but does not necessarily reflect the consensus of national of the lean season. food security partners. • The June to September 2019 rainy season is forecasted to be above average. This is anticipated to lead to flooding in mid-2019 and increase the prevalence of waterborne disease. -

Darfur, Sudan: the Responsibility to Protect

House of Commons International Development Committee Darfur, Sudan: The responsibility to protect Fifth Report of Session 2004–05 Volume II Oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 16 March 2005 HC 67-II [Incorporating HC 67-i to -vi] Published 30 March 2005 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £18.50 The International Development Committee The International Development Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for International Development and its associated public bodies. Current membership Tony Baldry MP (Conservative, Banbury) (Chairman) John Barrett MP (Liberal Democrat, Edinburgh West) Mr John Battle MP (Labour, Leeds West) Hugh Bayley MP (Labour, City of York) Mr John Bercow MP (Conservative, Buckingham) Ann Clwyd MP (Labour, Cynon Valley) Mr Tony Colman MP (Labour, Putney) Mr Quentin Davies MP (Conservative, Grantham and Stamford) Mr Piara S Khabra MP (Labour, Ealing Southall) Chris McCafferty MP (Labour, Calder Valley) Tony Worthington MP (Labour, Clydebank and Milngavie) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/indcom Committee staff The staff of the Committee are Alistair Doherty (Clerk), Hannah Weston (Second Clerk), Alan Hudson and Anna Dickson (Committee Specialists), Katie Phelan (Committee Assistant), Jennifer Steele (Secretary) and Philip Jones (Senior Office Clerk). -

Sudan a Country Study.Pdf

A Country Study: Sudan An Nilain Mosque, at the site of the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Helen Chapin Metz Research Completed June 1991 Table of Contents Foreword Acknowledgements Preface Country Profile Country Geography Society Economy Transportation Government and Politics National Security Introduction Chapter 1 - Historical Setting (Thomas Ofcansky) Early History Cush Meroe Christian Nubia The Coming of Islam The Arabs The Decline of Christian Nubia The Rule of the Kashif The Funj The Fur The Turkiyah, 1821-85 The Mahdiyah, 1884-98 The Khalifa Reconquest of Sudan The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1899-1955 Britain's Southern Policy Rise of Sudanese Nationalism The Road to Independence The South and the Unity of Sudan Independent Sudan The Politics of Independence The Abbud Military Government, 1958-64 Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69 The Nimeiri Era, 1969-85 Revolutionary Command Council The Southern Problem Political Developments National Reconciliation The Transitional Military Council Sadiq Al Mahdi and Coalition Governments Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment (Robert O. Collins) Physical Setting Geographical Regions Soils Hydrology Climate Population Ethnicity Language Ethnic Groups The Muslim Peoples Non-Muslim Peoples Migration Regionalism and Ethnicity The Social Order Northern Arabized Communities Southern Communities Urban and National Elites Women and the Family Religious -

Sudan: Interaction Between International and National Judicial Responses to the Mass Atrocities in Darfur

SUDAN: INTERACTION BETWEEN INTERNATIONAL AND NATIONAL JUDICIAL RESPONSES TO THE MASS ATROCITIES IN DARFUR BY SIGALL HOROVITZ DOMAC/19, APRIL 2013 ABOUT DOMAC THE DOMAC PROJECT focuses on the actual interaction between national and international courts involved in prosecuting individuals in mass atrocity situations. It explores what impact international procedures have on prosecution rates before national courts, their sentencing policies, award of reparations and procedural legal standards. It comprehensively examines the problems presented by the limited response of the international community to mass atrocity situations, and offers methods to improve coordination of national and international proceedings and better utilization of national courts, inter alia, through greater formal and informal avenues of cooperation, interaction and resource sharing between national and international courts. THE DOMAC PROJECT is a research program funded under the Seventh Framework Programme for EU Research (FP7) under grant agreement no. 217589. The DOMAC project is funded under the Socio-economic sciences and Humanities Programme for the duration of three years starting 1st February 2008. THE DOMAC PARTNERS are Hebrew University, Reykjavik University, University College London, University of Amsterdam, and University of Westminster. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Sigall Horovitz is a PhD candidate at Faculty of Law of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. She holds an LL.M. from Columbia University (2003). Ms. Horovitz worked as a Legal Officer at the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, during 2005-2008. She also served with the Office of the Prosecution in the Special Court for Sierra Leone, in 2003-2004 and in 2010. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank the interviewees and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input. -

COUNTRY Food Security Update

SUDAN Food Security Outlook Update April 2017 Food security continues to deteriorate in South Kordofan and Jebel Marra KEY MESSAGES By March/April 2017, food insecurity among IDPs and poor residents in Food security outcomes, April to May 2017 SPLM-N areas of South Kordofan and new IDPs in parts of Jabal Mara in Darfur has already deteriorated to Crisis (IPC Phase 3) and is likely to deteriorate to Emergency (IPC Phase 4) by May/June through September 2017 due to displacement, restrictions on movement and trade flows, and limited access to normal livelihoods activities. Influxes of South Sudanese refugees into Sudan continued in March and April due to persistent conflict and severe acute food insecurity in South Sudan. As March 31, more than 85,000 South Sudanese refugees have arrived into Sudan since the beginning of 2017, raising total number arrived to nearly 380,000 South Sudanese refugees since the start of the conflict in December 2013. Following above-average 2016/17 harvests, staple food prices either remained stable or started increases between February and March, particularly in some arid areas of Darfur and Red Sea states, and South Source: FEWS NET Kordofan, which was affected by dryness in 2016. Prices remained on Projected food security outcomes, June to September average over 45 percent above their respective recent five-year 2017 average. Terms of trade (ToT) between livestock and staple foods prices have started to be in favor of cereal traders and producers since January 2017. CURRENT SITUATION Staple food prices either remained stable or started earlier than anticipated increases, particularly in the main arid and conflicted affected areas of Darfur, Red Sea and South Kordofan states between February and March. -

General Presentation of Results

HUMANITARIAN AID ORGANISATION Return-oriented Profiling in the Southern Part of West Darfur and corresponding Chadian border area General presentation of results July 2005 INDEX INTRODUCTION pag. 3 PART 1: ANALYSIS OF MAIN TRENDS AND ISSUES IDENTIFIED pag. 6 Chapter 1: Demographic Background pag. 6 1.1 Introduction pag. 6 1.2 The tribes pag. 8 1.3 Relationship between African and Arabs tribes pag. 11 Chapter 2: Displacement and Return pag. 13 2.1 Dispacement pag. 13 2.2 Return pag. 16 2.3 The creation of “model” villages pag. 17 Chapter 3: The Land pag. 18 3.1 Before the crisis pag. 18 3.2 After the crisis pag. 19 Chapter 4: Security pag. 22 4.1 Freedom of movement pag. 22 4.2 Land and demography pag. 23 PART 2: ANALYSIS OF THE SECTORAL ISSUES pag. 24 Chapter 1: Sectoral Gaps and Needs pag. 24 1.1 Health pag. 24 1.2 Education pag. 27 1.3 Water pag. 32 1.4 Shelter pag. 36 1.5 Vulnerable pag. 37 1.6 International Presence pag. 38 PART 3: SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS pag. 42 Annex 1: Maps pag. 45 i Bindisi/Chadian Border pag. 45 ii Um-Dukhun/Chadian Border pag. 46 iii Mukjar pag. 47 iiii Southern West Darfur – Overview pag. 48 Annex 2: Geographical Summary of the Villages Profiled pag. 49 i Bindisi Administrative Unit pag. 49 ii Mukjar Administrative Unit pag. 61 iii Um-Dukhun Administrative Unit pag. 71 iiii Chadian Border pag. 91 iiiii Other Marginal Areas (Um-Kher, Kubum, Shataya) pag. 102 INTRODUCTION The current crisis has deep roots in the social fabric of West Darfur.