Remembering Angola

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Following Is Most of the Text of the Presentation I Did at Readercon 29

The following is most of the text of the presentation I did at Readercon 29. I ran out of time, so I wasn't able to give the entire talk. And my Powerpoint file became corrupted, so I gave the presentation without the images, as I'd originally planned. Here, then, is the original, as requested by a couple of the folks who attended the presentation. THE HISTORY OF HORROR LITERATURE IN AFRICA IN THE 20TH CENTURY Horror literature has not been restricted to the United States, the United Kingdom, and Europe, despite what critics and historians of the genre assume. Most countries which have a flourishing market for popular literature have seen natively-written horror fiction, whether in the form of dime novels, short stories, or novels. This is true of the European countries, whose horror writers are given at least a cursory mention in the broader types of horror criticism. But this is also true of countries outside of Europe, and in countries and continents where Western horror critics dare not tread, like Africa. Now, a thorough history of African horror literature is beyond the time I have today, so what follows is going to be a more limited coverage, of African horror literature in the twentieth century. I’ll be going alphabetically and chronologically through three time periods: 1901-1940, 1941-1970, and 1971-2000. I’d love to be able to tell you a unified theory of African horror literature for those time periods, but there isn’t one. Africa is far too large for that. -

Portuguese Language in Angola: Luso-Creoles' Missing Link? John M

Portuguese language in Angola: luso-creoles' missing link? John M. Lipski {presented at annual meeting of the AATSP, San Diego, August 9, 1995} 0. Introduction Portuguese explorers first reached the Congo Basin in the late 15th century, beginning a linguistic and cultural presence that in some regions was to last for 500 years. In other areas of Africa, Portuguese-based creoles rapidly developed, while for several centuries pidginized Portuguese was a major lingua franca for the Atlantic slave trade, and has been implicated in the formation of many Afro- American creoles. The original Portuguese presence in southwestern Africa was confined to limited missionary activity, and to slave trading in coastal depots, but in the late 19th century, Portugal reentered the Congo-Angola region as a colonial power, committed to establishing permanent European settlements in Africa, and to Europeanizing the native African population. In the intervening centuries, Angola and the Portuguese Congo were the source of thousands of slaves sent to the Americas, whose language and culture profoundly influenced Latin American varieties of Portuguese and Spanish. Despite the key position of the Congo-Angola region for Ibero-American linguistic development, little is known of the continuing use of the Portuguese language by Africans in Congo-Angola during most of the five centuries in question. Only in recent years has some attention been directed to the Portuguese language spoken non-natively but extensively in Angola and Mozambique (Gonçalves 1983). In Angola, the urban second-language varieties of Portuguese, especially as spoken in the squatter communities of Luanda, have been referred to as Musseque Portuguese, a name derived from the KiMbundu term used to designate the shantytowns themselves. -

On Literature and National Culture

ON LITERATU RE AND NAT IONAL CULTURE1 By Agostinho Neto 0 O.V LITERATURg2 COmrades: It is with the greatest pleasure that I attend this formal ceremony for the installation of the Governing Bodies of the Angolan Writers' Union. As all of you will understand, only the guarantees offered by the other members of the General Assembly and by the COmrade Secretary- General were able to convince me to accept one more obligation added to so many others. Nevertheless, I wish to thank the Angolan Writers ' Union for this kind gesture and to express my hope that whenever it may be necessary for me to make my contribution to the Union that the COmrades as a whole or individually will not hesitate to put before me the problems that go along with these new duties that I now assume . I wish to use this occasion to pay homage to those COmrade writers who before and after the national liberation struggle suffered persecution, to those who lost their freedom in prison or exile, and to those who inside the country were politically segr~gated and thus placed in unusual situations. I also wish to join with all the COmrades here in the homage that was paid to those Comrades who heroically made the ultimate sacrifice during the national liberation struggle, and who today are no longer with us. Comrades: We have taken one more step forward in our national life with the forming of this Writers' Union which continues the literary traditions of the period of resistence against colon ialism. During that period, and in spite of colonial-fascist repression, a task was accomplished that will go down in the annals of Angola' s revolutionary history as a valuable contri bution to the Victory of the Angolan People. -

Tell Me Still, Angola the False Thing That Is Dystopia

https://doi.org/10.22409/gragoata.v26i55.47864 Tell me Still, Angola the False Thing that is Dystopia Solange Evangelista Luis a ABSTRACT José Luis Mendonça’s book Angola, me diz ainda (2017) brings together poems from the 1980s to 2016, unveiling a constellation of images that express the unfulfilled utopian Angolan dream. Although his poems gravitate around his personal experiences, they reflect a collective past. They can be understood as what Walter Benjamin called monads: historical objects (BENJAMIN, 2006, p. 262) based on the poet’s own experiences, full of meaning, emotions, feelings, and dreams. Through these monadic poems, his poetry establishes a dialogue with the past. The poet’s dystopic present is that of an Angola distanced from the dream manifested in the insubmissive poetry of Agostinho Neto and of the Message Generation, which incited decolonization through a liberation struggle and projected a utopian new nation. Mendonça revisits Neto’s Message Generation and its appeal to discover Angola: unveiling a nation with a broken dream and a dystopic present, denouncing a future that is still to come. The poet’s monads do not dwell on dystopia but wrestle conformism, fanning the spark of hope (BENJAMIN, 2006, p. 391). They expose what Adorno named the false thing (BLOCH, 1996, p. 12), sparking the longing for something true: reminding the reader that transformation is inevitable. Keywords: Angolan Literature. José Luís Mendonça. Lusophone African Literature. Dystopia. Walter Benjamin. Recebido em: 29/12/2020 Aceito em: 27/01/2021 a Universidade do Porto, Centro de Estudos Africanos, Porto, Portugal E-mail: [email protected] How to cite: LUIS, S.E. -

Ethnic Groups

About Tutorial Glossary Documents Images Maps Google Earth Please provide feedback! Click for details People and the River You are here: Home>People and the River >People>Cultural Diversity >Ethnic Groups Introduction People History Cultural Diversity Ethnic Groups Ethnic Groups Traditional Knowledge Stories This section provides only a very general description of the ethnic groups living in Culture & Water Kunene basin, due to contradictory information in different literature sources and the Socio- economics general lack of recent studies following the war in Angola. People and Environment Human Development It should be noted that the concept of "ethnic groups" is becoming increasingly Initiatives controversial. This is in part due to the fact that the description of ethnic groups was References often been made by colonial powers and does not necessarily correspond to the Explore the sub- basins of the people's understanding of their own identity. Another reason is the strong mixing of Kunene River the autochthonous populations, which has led to a kind of "melting" of the homogeneous "ethnic" groups once determined by certain characteristics. Video Interviews about the integrated and transboundary management of the Kunene River basin Distribution of ethnic groups across the Kunene River basin. View a historical timeline of the Source: AHT GROUP AG 2010 Kunene basin countries, ( click to enlarge ) including water agreements & infrastructure Bantu- speaking Groups The majority of the basin’s population belongs to the group of Bantu- speakers which can in turn be divided into numerous groups and sub- groups. Ovimbundu The Upper Kunene basin in Angola is partly inhabited by Ovimbundu families or individuals who speak the Bantu language of Umbundu and have a relatively send a general website homogeneous culture. -

Urban Poverty in Luanda, Angola CMI Report, Number 6, April 2018

NUMBER 6 CMI REPORT APRIL 2018 AUTHORS Inge Tvedten Gilson Lázaro Urban poverty Eyolf Jul-Larsen Mateus Agostinho in Luanda, COLLABORATORS Nelson Pestana Angola Iselin Åsedotter Strønen Cláudio Fortuna Margareht NangaCovie Urban poverty in Luanda, Angola CMI Report, number 6, April 2018 Authors Inge Tvedten Gilson LázAro Eyolf Jul-Larsen Mateus Agostinho Collaborators Nelson PestanA Iselin Åsedotter Strønen Cláudio FortunA MargAreht NAngACovie ISSN 0805-505X (print) ISSN 1890-503X (PDF) ISBN 978-82-8062-697-4 (print) ISBN 978-82-8062-698-1 (PDF) Cover photo Gilson LázAro CMI Report 2018:06 Urban poverty in Luanda, Angola www.cmi.no Table of content 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Poverty in AngolA ................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2 AnalyticAl ApproAch ............................................................................................................................. 6 1.3 Methodologies ..................................................................................................................................... 7 1.4 The project sites .................................................................................................................................. 9 2 Structural context ....................................................................................................................................... -

Angola, a Nation in Pieces in José Eduardo Agualusa's Estação Das

Angola, a Nation in Pieces in José Eduardo Agualusa’s Estação das chuvas RAQUEL RIBEIRO University of Edinburgh Abstract: In this article, I examine José Eduardo Agualusa’s Estação das chuvas (1996), as a novel that lays bare the contradictions of the MPLA’s revolutionary process after Angola’s independence. I begin with a discussion of the proximity between trauma and (the impossibility) of fiction. I then consider the challenges Angolan writers face in presenting an alternative discourse to the “one-party, one-people, one-nation” narrative propagated by the MPLA). Finally, I discuss how Estação das chuvas, which complicates both truth/verisimilitud and history/fiction, presents an alternative vision of Angola’s national narrative. Keywords: Angolan literature; MPLA; UNITA; Truth and fiction; Nation The Angolan civil war broke out in 1975 and lasted 27 years. Yet there are still very few literary accounts of the conflict by Angolan writers. Novels about the civil war have been scarce, and there are few first person or testimonial records by those who participated directly in the conflict, as victims or perpetrators. The war was an enduring presence in Angolan literature in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, but always as something distant. Generally, books do not explicitly evoke the conflict, international military interventions (South African, Soviet, Cuban), its conscripts, prisoners, and atrocities perpetrated by both the MPLA and UNITA. Texts that dealt with it at the time left its contradictions and ideological complexities aside, focusing instead on how it forced millions to migrate to 57 Ribeiro Luanda, its consequences for families, and the hardships of daily life for certain classes of Angolans. -

A HISTORY of TWENTIETH CENTURY AFRICAN LITERATURE.Rtf

A HISTORY OF TWENTIETH CENTURY AFRICAN LITERATURES Edited by Oyekan Owomoyela UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS © 1993 by the University of Nebraska Press All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America The paper in this book meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 239.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A History of twentieth-century African literatures / edited by Oyekan Owomoyela. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8032-3552-6 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8032-8604-x (pbk.: alk. paper) I. Owomoyela, Oyekan. PL80I0.H57 1993 809'8896—dc20 92-37874 CIP To the memory of John F. Povey Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction I CHAPTER I English-Language Fiction from West Africa 9 Jonathan A. Peters CHAPTER 2 English-Language Fiction from East Africa 49 Arlene A. Elder CHAPTER 3 English-Language Fiction from South Africa 85 John F. Povey CHAPTER 4 English-Language Poetry 105 Thomas Knipp CHAPTER 5 English-Language Drama and Theater 138 J. Ndukaku Amankulor CHAPTER 6 French-Language Fiction 173 Servanne Woodward CHAPTER 7 French-Language Poetry 198 Edris Makward CHAPTER 8 French-Language Drama and Theater 227 Alain Ricard CHAPTER 9 Portuguese-Language Literature 240 Russell G. Hamilton -vii- CHAPTER 10 African-Language Literatures: Perspectives on Culture and Identity 285 Robert Cancel CHAPTER II African Women Writers: Toward a Literary History 311 Carole Boyce Davies and Elaine Savory Fido CHAPTER 12 The Question of Language in African Literatures 347 Oyekan Owomoyela CHAPTER 13 Publishing in Africa: The Crisis and the Challenge 369 Hans M. -

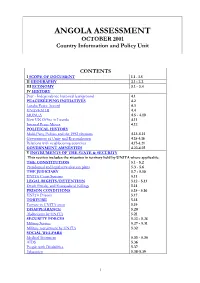

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.2 III ECONOMY 3.1 - 3.4 IV HISTORY Post - Independence historical background 4.1 PEACEKEEPING INITIATIVES 4.2 Lusaka Peace Accord 4.3 UNAVEM III 4.4 MONUA 4.5 - 4.10 New UN Office in Luanda 4.11 Internal Peace Moves 4.12 POLITICAL HISTORY Multi-Party Politics and the 1992 elections 4.13-4.14 Government of Unity and Reconciliation 4.15-4.16 Relations with neighbouring countries 4.17-4.21 GOVERNMENT AMNESTIES 4.22-4.25 V INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE & SECURITY This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable. THE CONSTITUTION 5.1 - 5.2 Presidential and legislative election plans 5.3 - 5.6 THE JUDICIARY 5.7 - 5.10 UNITA Court Systems 5.11 LEGAL RIGHTS/DETENTION 5.12 - 5.13 Death Penalty and Extrajudicial Killings 5.14 PRISON CONDITIONS 5.15 - 5.16 UNITA Prisons 5.17 TORTURE 5.18 Torture in UNITA areas 5.19 DISAPPEARANCE 5.20 Abductions by UNITA 5.21 SECURITY FORCES 5.22 - 5.26 Military Service 5.27 - 5.31 Military recruitment by UNITA 5.32 SOCIAL WELFARE Medical Treatment 5.33 - 5.35 AIDS 5.36 People with Disabilities 5.37 Education 5.38-5.39 1 VI HUMAN RIGHTS- GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE SITUATION Introduction 6.1 SECURITY SITUATION Recent developments in the Civil War 6.2 - 6.17 Security situation in Luanda 6.18 - 6.19 Landmines 6.20 - 6.22 Human Rights monitoring 6.23 - 6.26 VII SPECIFIC GROUPS REFUGEES 7.1 Internally Displaced Persons & Humanitarian Situation 7.2-7.5 UNITA 7.6-7.8 Recent Political History of UNITA 7.9-7.12 UNITA-R 7.13-7.14 UNITA Military Wing 7.15-7.20 Surrendering UNITA Fighters 7.21 Sanctions against UNITA 7.22-7.25 F.L.E.C/CABINDANS 7.26 History of FLEC 7.27-7.28 Recent FLEC activity 7.29-7.34 The future of Cabindan separatists 7.35 ETHNIC GROUPS 7.36-7.37 Bakongo 7.38-7.46 WOMEN 7.47 Discrimination against women 7.48-7.59 CHILDREN 7.50-7.55 VIII RESPECT FOR CIVIL LIBERTIES This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable. -

Examining Angolan Fiction

Phyllis Peres, Inc. NetLibrary. Transculturation and resistance in Lusophone African narrative. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1997. x + 131 pp. ISBN 978-0-8130-2368-7. Reviewed by Elizabeth Blakesley Lindsay Published on H-AfrLitCine (February, 1998) Although Phyllis Peres doesn't mention it, this es the post-independence works of Rui and the work is an update of National Literary Identity in continued efforts to define nation in the post-colo‐ Contemporary Angolan Prose Fiction, the fne dis‐ nial era. sertation she wrote at the University of Minnesota Throughout, Peres offers strong evidence (1986) as Phyllis A. Reisman. from the text for her thesis, and provides insight‐ Peres begins by examining the history and ful analysis of those textual examples. Peres has context of Angolan writing, noting the importance been able to meet and consult with all four of the of events from early colonial history and the as‐ authors she studies, a fact which greatly enriches similation policies of the Portuguese to Lusotropi‐ her insights into a number of works and issues. calismo and the Generation of 1950. All this leads Peres concludes by reminding us that Angolan Peres to defining transculturation, an anthropo‐ writing is different than other post-colonial logical concept she has adopted as a theoretical African writing, pointing to Angola's prolonged framework for examining the process and prod‐ fight for independence and the brutal civil war, uct of Angolan literature. Transculturation marks which has comprised most of its post-colonial a movement toward a national culture or a na‐ years. Peres states that "for all the common tional literary identity and works as a means of ground that one can fnd in post-colonial African resisting colonial acculturation. -

Angola in Perspective

© DLIFLC Page | 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Geography ......................................................................................................... 5 Country Overview ........................................................................................................... 5 Geographic Regions and Topographic Features ............................................................. 5 Coastal Plain ............................................................................................................... 5 Hills and Mountains .................................................................................................... 6 Central-Eastern Highlands .......................................................................................... 6 Climate ............................................................................................................................ 7 Rivers .............................................................................................................................. 8 Major Cities .................................................................................................................... 9 Luanda....................................................................................................................... 10 Huambo ..................................................................................................................... 11 Benguela ................................................................................................................... 11 Cabinda -

Diagnóstico Transfronteiriço Do Okavango – Análise Socioeconómica

Diagnóstico Transfronteiriço Bacia do Okavango Análise Socioeconómica Angola Rute Saraiva Julho de 2009 TDA Angola Análise Socioeconómica Diagnóstico Transfronteiriço Bacia do Okavango Análise Socioeconómica Angola Equipa: Rute Saraiva (Coordenação e Redacção) Catarina Cunha (Sistema de Informação Geográfica) Cristina Rodrigues (Pesquisa Qualitativa) Priscila Cahicava (Inquiridora – Província do Kuando Kubango) Manuel Paulo (Pesquisa Qualitativa) Luís Lacho (Inquiridor – Província do Kuando Kubango) Yuri Alberto (Diagnóstico Rural Participativo) Manuel Costa (Inquiridor – Província da Huíla) Camilo Amado (Diagnóstico Rural Participativo) João King (Inquiridor – Província da Huíla) Délcio Joaquim (Pesquisa Quantitativa) Dinilson Manhita (Inquiridor – Província do Huambo) Jeremias Ntyamba (Pesquisa Quantitativa) Wilker Flor Maria de Fátima Ruben (Inquiridora – Província do es (Inquiridor – Província do Huambo) Kuando Kubango) Joaquim Oliveira (Inquiridor – Província do Huambo) Ruth Cachicava (Inquiridora – Província do Kuando Vladimir Dieiro (Inquiridor – Província do Bié) Kubango) Latino João (Inquiridor – Província do Bié) Maria Marcelina (Inquiridora – Província do Kuando José Chingui (Inquiridor – Província do Bié) Kubango) 2 TDA Angola Análise Socioeconómica Índice 1. Resumo Executivo ................................................................................................................. 7 2. Metodologia .........................................................................................................................