SARAJEVO in the WILDERNESS of POST- SOCIALIST TRANSITION: the NEOLIBERAL URBAN TRANSFORMATION of the CITY IS B N: 978 - 88 96951 23 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

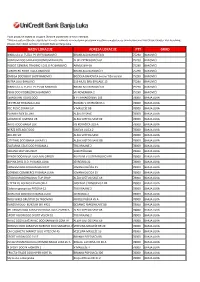

Spisak Za Kupovinu Na Rate

Popis prodajnih mjesta sa uslugom Obročne otplate bez kamata i naknada. *Plaćanje putem Obročne otplate bez kamata i naknada na navedenim prodajnim mjestima omogućeno je svim korisnicima Visa Classic Charge i Visa Revolving (Classic, Net i Gold) karticom UniCredit Bank ad Banja Luka. NAZIV LOKACIJE ADRESA LOKACIJE PTT GRAD BINGO d.o.o. TUZLA PJ 19 FIS BANOVIĆI BRANILACA BANOVIĆA B 75290 BANOVIĆI KONZUM DOO SARAJEVO KONZUM BIH K326 ALIJE IZETBEGOVIĆA 61 75290 BANOVIĆI ROBOT GENERAL TRADING CO D.O PC BANOVIĆI ARMIJE BIH 6A 75290 BANOVIĆI EUROHERC PODR TUZLA BANOVIĆI BRANILACA BANOVIĆI 4 75290 BANOVIĆI OMEGA DOO BEKO SHOP BANOVIĆI BOŽIĆKA BANOVIĆA 6-novi Tržni centar 75290 BANOVIĆI ASTRA DOO BANOVIĆI 119 MUSL BRD BRIGADE 15 75290 BANOVIĆI BINGO d.o.o. TUZLA PJ 23 SM BANOVIĆI BRANILACA BANOVIĆA B 75290 BANOVIĆI PEKO DOO PODRUŽNICA BANOVIĆI VII NOVEMBRA 2 75290 BANOVIĆI SEBASTIJAN TOURS DOO K P I KARAÐORÐEV 103 78000 BANJA LUKA CENTRUM TR BANJA LUKA BUDŽAK V.OSTROŠKOG 1 78000 BANJA LUKA KEC PUŠIĆ ZORAN S.P. V MASLEŠE BB 78000 BANJA LUKA PLANIKA FLEX B.LUKA ALEJA SV SAVE 78000 BANJA LUKA JAĆIMOVIĆ JUVENTA UR ALEJA SVETOG SAVE 69 78000 BANJA LUKA ARTIST DOO BANJA LUK I G KOVAČIĆA 203-A 78000 BANJA LUKA NERZZ BEŠLAGIĆ DOO GAJEVA ULICA 2 78000 BANJA LUKA AB LINE SIX ALEJA SVETOG SAVE 78000 BANJA LUKA CITYTIME DOO BANJA LUKA PJ 1 ALEJA SVETOG SAVE BB 78000 BANJA LUKA ZLATARNA CELJE DOO PJ BANJA L TRG KRAJINE 2 78000 BANJA LUKA VERANO MOTORS RENT SUBOTIČKA BB 78000 BANJA LUKA DEKOR DOO BANJA LUKA MALOPROD BULEVAR V S STEPANOVIĆA BB 78000 BANJA LUKA ALPINA BH D.O.O. -

Godišnji Izvještaj Za 2016

EDUS- Godišnji izvještaj za 2016. GODIŠNJI 2016. IZVJEŠTAJ [NARATIVNI GODIŠNJI IZVJEŠTAJ] [Pregled najvažnijih aktivnosti, projekata i postignuća organizacije EDUS-Edukacija za sve u 2016. godini.] Mjedenica 34, 71000 Sarajevo [email protected] www.edusbih.org EDUS- Godišnji izvještaj za 2016. SADRŽAJ: 1. KRATAK PREGLED GLAVNIH DEŠAVANJA ..........................................................2 1.1. PRESJEK SVIH ŠEST GODINA EDUS-a.............................................................2 1.2. KRATAK PREGLED AKTIVNOSTI U 2016-oj ......................................................3 2. RAD S DJECOM PO NAUČNOJ METODOLOGIJI....................................................4 2.1. EDUS UČIONICE I VRTIĆKE GRUPE U OKVIRU ZAVODA MJEDENICA.....8 2.2. PROGRAM RANE INTERVENCIJE..................................................................9 2.3. DOPUNSKA NASTAVA..................................................................................10 2.4. LJETNA ŠKOLA..............................................................................................10 3. EDUKACIJA STRUČNJAKA.....................................................................................11 3.1. EDUKACIJA KROZ RAD U EDUS PROGRAMU............................................11 3.2. EDUKACIJA STRUČNJAKA ŠIROM BIH KROZ PROJEKAT S UNICEF-om I FEDERALNIM MINISTARSTVOM ZDRAVSTVA............................................11 3.3. TERCIJARNO OBRAZOVANJE EDUS-OVIH STRUČNJAKA U INOSTRANSTVU............................................................................................14 -

Neo-Liberalism, the Islamic Revival, and Urban Development in Post-War, Post-Socialist Sarajevo

Neo-Liberalism, the Islamic Revival, and Urban Development in Post-War, Post-Socialist Sarajevo By Zev Moses A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Geography Department of Geography and Program in Planning University of Toronto © Copyright by Zev Moses 2012 Neo-Liberalism, the Islamic Revival, and Urban Development in Post-War, Post-Socialist Sarajevo Zev Moses Master of Arts in Geography Department of Geography and Program in Planning University of Toronto 2012 Abstract This thesis examines the confluence between pan-Islamist politics, neo-liberalism and urban development in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. After tracing a history of the Islamic revival in Bosnia, I examine the results of neo-liberal policy in post-war Bosnia, particularly regarding the promises of neo-liberal institutions and think tanks that privatization and inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) would de-politicize the economy and strip ethno-religious nationalist elites of their power over state-owned firms. By analyzing three prominent new urban developments in Sarajevo, all financed by FDI from the Islamic world and brought about by the privatization of urban real-estate, I show how neo-liberal policy has had unintended outcomes in Sarajevo that contradict the assertions of policy makers. In examining urban change, I bring out the role played by the city in mediating between both elites and citizens, and between the seemingly contradictory projects of pan-Islamism and neo- liberalism. ii Acknowledgements I would like to extend my gratitude to everyone who helped me in one way or another with this project. -

Geopolitical and Urban Changes in Sarajevo (1995 – 2015)

Geopolitical and urban changes in Sarajevo (1995 – 2015) Jordi Martín i Díaz Aquesta tesi doctoral està subjecta a la llicència Reconeixement- NoComercial – SenseObraDerivada 3.0. Espanya de Creative Commons. Esta tesis doctoral está sujeta a la licencia Reconocimiento - NoComercial – SinObraDerivada 3.0. España de Creative Commons. This doctoral thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0. Spain License. Facultat de Geografia i Història Departament de Geografia Programa de Doctorat “Geografia, planificació territorial i gestió ambiental” Tesi doctoral Geopolitical and urban changes in Sarajevo (1995 – 2015) del candidat a optar al Títol de Doctor en Geografia, Planificació Territorial i Gestió Ambiental Jordi Martín i Díaz Directors Dr. Carles Carreras i Verdaguer Dr. Nihad Čengi ć Tutor Dr. Carles Carreras i Verdaguer Barcelona, 2017 This dissertation has been funded by the Program Formación del Profesorado Universitario of the Spanish Ministry of Education, fellowship reference (AP2010- 3873). Als meus pares i al meu germà. Table of contents Aknowledgments Abstract About this project 1. Theoretical and conceptual approach 15 Socialist and post-socialist cities 19 The question of ethno-territorialities 26 Regarding international intervention in post-war contexts 30 Methodological approach 37 Information gathering and techniques 40 Structure of the dissertation 44 2. The destruction and division of Sarajevo 45 Sarajevo: common life and urban expansion until early 1990s 45 The urban expansion 48 The emergence of political pluralism 55 Towards the ethnic division of Sarajevo: SDS’s ethno-territorialisation campaign and the international partiality in the crisis 63 The Western policy towards Yugoslavia: paving the way for the violent ethnic division of Bosnia 73 The siege of Sarajevo 77 Deprivation, physical destruction and displacement 82 The international response to the siege 85 SDA performance 88 Sarajevo’s ethno-territorial division in the Dayton Peace Agreement 92 The DPA and the OHR’s mission 95 3. -

Z a K Lj U Č a K

Bosna i Hercegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina Federacija Bosne i Hercegovine Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina KANTON SARAJEVO CANTON SARAJEVO Vlada Government Broj: 02-05-7971-12/16 Sarajevo, 10.03.2016. godine Na osnovu člana 26. i 28. stav 4. Zakona o Vladi Kantona Sarajevo („Službene novine Kantona Sarajevo“, “, broj: 36/14 - Novi pre čiš ćeni tekst i 37/14 - ispravka), a u vezi člana 27. stav 1. alineja 13. Zakona o ustanovama („Službeni list RBiH“, br. 6/92, 8/93 i 13/94), Vlada Kantona Sarajevo na 35. sjednici održanoj 10.03.2016. godine, donijela je sljede ći Z A K LJ U Č A K 1. Prihvata se Izvještaj o radu i finansijskom poslovanju Javne ustanove Centar za kulturu Kantona Sarajevo za 2015. godinu. 2. Izvještaj iz ta čke 1. ovog Zaklju čka dostavlja se Skupštini Kantona Sarajevo na razmatranje i usvajanje. P R E M I J E R Elmedin Konakovi ć Dostaviti: 1. Predsjedavaju ća Skupštine Kantona Sarajevo 2. Skupština Kantona Sarajevo 3. Premijer Kantona Sarajevo 4. Ministarstvo kulture i sporta Kantona Sarajevo 5. JU Centar za kulturu Kantona Sarajevo (putem Ministarstva kulture i sporta) 6. Evidencija 7. A r h i v a web: http://vlada.ks.gov.ba e-mail: [email protected] Tel: + 387 (0) 33 562-068, 562-070 Fax: + 387 (0) 33 562-211 Sarajevo, Reisa Džemaludina Čauševi ća 1 Bosna i Hercegovina Federacija Bosne i Hercegovine KANTON SARAJEVO SKUPŠTINA KANTONA SARAJEVO Na osnovu člana 117., a u vezi člana 120. stav 2. Poslovnika Skupštine Kantona Sarajevo („Službene novine Kantona Sarajevo", broj 41/12 - Drugi novi prečišćeni tekst, 15/13 i 47/13), Skupština Kantona Sarajevo na sjednici održanoj dana . -

Snimajuce-Lokacije.Pdf

Elma Tataragić Tina Šmalcelj Bosnia and Herzegovina Filmmakers’ Location Guide Sarajevo, 2017 Contents WHY BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 3 FACTS AND FIGURES 7 GOOD TO KNOW 11 WHERE TO SHOOT 15 UNA-SANA Canton / Unsko-sanski kanton 17 POSAVINA CANTON / Posavski kanton 27 Tuzla Canton / Tuzlanski kanton 31 Zenica-DoboJ Canton / Zeničko-doboJski kanton 37 BOSNIAN PODRINJE CANTON / Bosansko-podrinJski kanton 47 CENTRAL BOSNIA CANTON / SrednJobosanski kanton 53 Herzegovina-neretva canton / Hercegovačko-neretvanski kanton 63 West Herzegovina Canton / Zapadnohercegovački kanton 79 CANTON 10 / Kanton br. 10 87 SARAJEVO CANTON / Kanton SaraJevo 93 EAST SARAJEVO REGION / REGION Istočno SaraJevo 129 BANJA LUKA REGION / BanJalučka regiJA 139 BIJELJina & DoboJ Region / DoboJsko-biJELJinska regiJA 149 TREBINJE REGION / TrebinJska regiJA 155 BRčKO DISTRICT / BRčKO DISTRIKT 163 INDUSTRY GUIDE WHAT IS OUR RECORD 168 THE ASSOCIATION OF FILMMAKERS OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 169 BH FILM 2001 – 2016 170 IMPORTANT INSTITUTIONS 177 CO-PRODUCTIONS 180 NUMBER OF FILMS PRODUCED 184 NUMBER OF SHORT FILMS PRODUCED 185 ADMISSIONS & BOX OFFICE 186 INDUSTRY ADDRESS BOOK 187 FILM SCHOOLS 195 FILM FESTIVALS 196 ADDITIONAL INFO EMBASSIES 198 IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS 204 WHERE TO STAY 206 1 Why BiH WHY BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA • Unspoiled natural locations including a wide range of natu- ral sites from mountains to seaside • Proximity of different natural sites ranging from sea coast to high mountains • Presence of all four seasons in all their beauty • War ruins which can be used -

Lokalni Ekološki Akcioni Plan Općine Centar Za Period 2019. – 2024

Općina Centar Sarajevo Lokalni ekološki akcioni plan Općine Centar za period 2019. – 2024. Sarajevo, novembar 2019. godine Lokalni ekološki akcioni plan općine Centar za period 2019.-2024. OPĆI PODACI Naručilac: Općina Centar - Sarajevo Projekat: Izrada lokalnog ekološkog akcionog plana općine Centar za period 2019.-2024. godina Projekat podržao: Fond za zaštitu okoliša Federacije BiH Naziv dokumenta: Lokalni plan zaštite okoliša općine Centar 2019.-2024. Period izrade maj 2019. - novembar 2019. godine dokumenta: Izvršilac Enova d.o.o. Podgaj 14 71000 Sarajevo tel: + 387 33 279 100 fax: + 387 33 279 108 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.enova.ba NLogic d.o.o. Tešanjska 24a 71000 Sarajevo tel: + 387 33 869 008 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.nlogic.ba 5 Lokalni ekološki akcioni plan općine Centar za period 2019.-2024. RADNI TIM OPĆINE CENTAR Služba Ime i prezime Funkcija Služba za finansije, privredu i Predrag Slomović, šef odsjeka Predsjednik Radnog tima lokalno-ekonomski razvoj (LER) Služba za urbanizam i zaštitu Amela Landžo, pomoćnica Zamjenica predsjednika Radnog tima okoliša Načelnika Služba za investicije, komunalni Samir Šehović, pomoćnik Član Radnog tima razvoj i planiranje Načelnika Služba za civilnu zaštitu i mjesne Vahid Bećirević, pomoćnik Član Radnog tima zajednice (MZ) Načelnika Služba za javne nabavke, zajedničke Samir Širić, šef odsjeka Član Radnog tima poslove i informatiku Inspektorat Vildana Taso, pomoćnik Članica Radnog tima Načelnika Služba za boračko-invalidsku Jasmina Fazlić, pomoćnik Članica Radnog tima -

Renata De Figueiredo Summa Enacting Everyday Boundaries in Post-Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina

Renata de Figueiredo Summa Enacting everyday boundaries in post-Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina: disconnection, re- appropriation and displacement(s) Tese de Doutorado Thesis presented to the Programa de Pós- graduação em Relações Internacionais of PUC- Rio in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doutor em Relações Internacionais. Advisor: Prof. João Franklin Abelardo Pontes Nogueira Rio de Janeiro December 2016 Renata de Figueiredo Summa Enacting everyday boundaries in post-Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina: disconnection, re- appropriation and displacement(s) Thesis presented to the Programa de Pós- graduação em Relações Internacionais of PUC- Rio in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doutor em Relações Internacionais. Approved by the undersigned Examination Committee. Prof. João Franklin Abelardo Pontes Nogueira Advisor PUC-Rio Prof. Jef Huysmans Queen Mary University of London Prof. James Matthews Davies University of Newcastle and PUC-Rio Prof. Roberto Vilchez Yamato PUC-Rio Profª Marta Regina Fernandez Y Garcia Moreno PUC-Rio Profª Mônica Herz Vice-Decana de Pós-Graduação do Centro de Ciências Sociais Rio de Janeiro, December 20th, 2016 All rights reserved. Renata de Figueiredo Summa Renata de Figueiredo Summa has a b.a. from University of São Paulo, a M.A. in International Relations from Sciences-Po Paris and a PHD in International Relations from PUC-Rio. Bibliographic data Summa, Renata de Figueiredo Enacting everyday boundaries in post-Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina : disconnection, reappropriation and displacement(s) / Renata de Figueiredo Summa ; advisor: João Franklin Abelardo Pontes Nogueira. – 2016. 267 f. : il. color. ; 30 cm Tese (doutorado)–Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Instituto de Relações Internacionais, 2016. -

1 SPISAK INSOLVENTNA PRAVNA I FIZIČKA LICA SA STANJEM NA DAN 30.4.2015.G

SPISAK INSOLVENTNA PRAVNA I FIZIČKA LICA SA STANJEM NA DAN 30.4.2015.g. - LISTA INSOLVENTNIH PRAVNIH I FIZIČKIH LICA 15 I VIŠE DANA SA PREKIDIMA Red NAZIV SJEDIŠTE ADRESA Transakcijski broj račun 1. AMILA KIOSK TRGOVKA VL ZUKIC EMINA GRADACAC GRADACAC M TITA BB 1610250020440081 2. ART ELECTRONIC DOO ZENICA ZENICA LONDZA 90 1610550030060041 3. BETAX DOO SARAJEVO SARAJEVO S GRAD HUREMUSA 17 1610000036420019 4. BIM TRANS DOO SARAJEVO SARAJEVO KURTA SHORKA 8 1610000124890033 5. BLICKO DOO TUZLA TUZLA SKPC MEJDAN BB 1610250033650026 6. DAN I NOC PEKARA DOO SARAJEVO SARAJEVO N GRAD ADEMA BUCE 7 1610000059500005 7. DOM ZDRAVLJA ZU BIHAC BIHAC PUT 5 KORPUSA BB 1610350000340027 8. DOM ZDRAVLJA ZU BIHAC BIHAC PUT 5 KORPUSA BB 1610350000340124 9. ENERGOMONT DOO BOSANSKA KRUPA BOSANSKA KRUPA 511 SBB BB 1610350017930007 10. FASHION & STYLE FACTORY DOO SARAJEVO TRG DJECE SARAJEVA 1 BBI CENTAR 1610000129590071 11. GARA TR VL SACIRA NOZIC MOSTAR MOSTAR KOCINE BB 1610000119770082 12. GOLDEN CLUB UR VL M CVITANOVIC MOSTAR MOSTAR KRALJA PETRA KRESIMIRA IV BB 1610200071500059 13. GOLDING DOO SARAJEVO SARAJEVO TOPAL OSMAN PASE 19 1610000096640044 14. GOLDING DOO SARAJEVO SARAJEVO TOPAL OSMAN PASE 19 1610000096640141 15. IPE BAU DOO ZAVIDOVICI ZAVIDOVICI RADNICKA ULICA BB ZAVIDOVICI 1610550030280037 16. JAVNI PRIJEVOZ STVARI VL T GRBESIC S BRIJEG SIROKI BRIJEG DOBRKOVICI BB 1610200061990179 17. KENIX DOO GORAZDE GORAZDE ZAIMA IMAMOVICA 48 1610300000640002 18. LEJLA 1 FRIZERSKI SALON VL LEJLA CORIC MOSTA MOSTAR ADEMA BUCA 3 1610200070850062 19. MAX MUSIC COMPANY DOO SARAJEVO SARAJEVO BISTRIK 9 1610000020920098 20. MELISSA NAS DOO BIHAC BIHAC DARIVALACA KRVI 86 1610350045390028 21. MIMA SZ ZLATARA VL DIZDAREVIC SABAHUDIN ZENIC ZENICA MARSALA TITA 48 1610550009250049 22. -

Annual Report/Godišnji Izvještaj 2008 Bosna Bank International D.D

Detalj sa svečanog otvorenja BBI Centra Detail from the official opening of the BBI Center BBI Centar BBI Center Početkom druge polovine 70-ih godina prošlog stoljeća na središnjem sarajevs- At the beginning of the late seventies of the last century a department store kom trgu izgrađena je robna kuća „Unima“. Bilo je to vrijeme kada se mislilo da će “Unima” was built in the Sarajevo square in the core of the city. That was a time izgradnjom velikih robnih kuća gradovi dobiti obilježja metropola, pa je uskoro when people thought that by building large department stores cities would be svaki veći grad u bivšoj državi imao svoju robnu kuću. Legenda kaže da su se marked as metropolis, so every large town in the former state had a department djeca ljeti na moru svađala oko toga čiji grad ima ljepšu i veću robnu kuću, pa store. The legend says that during summer, the children on vacation in the sea- su one, bez obzira koje ih je preduzeće izgradilo i otvorilo, počele imena dobi- side argued whose town had a better and larger department store. The depart- jati po gradovima u kojima su napravljene. Tako je „Unima“ promijenila ime u ment stores started getting names of the towns where they had been located „Sarajka“, ali je skoro niko od Sarajlija nije zvao tim imenom. Robna kuća u kojoj disregarding the companies that had built them. So, “Unima” changed name to se, kako se tada govorilo, moglo kupiti sve „od igle do lokomotive“ iz rata 1992- “Sarajka” but almost none of the citizens of Sarajevo called it by that name. -

Spisak Trgovaca Kod Kojih Možete Ostvariti Popust I Plaćati Na Rate

Spisak trgovaca kod kojih možete ostvariti popust i plaćati na rate GRAD DJELATNOST ADRESA BR. RATA POPUST Banovići ASTRA Obuća 119. Muslimanske brdske brigade 1 do 12 - BH TELECOM Telekomunikacije Branilaca Banovića bb do 12 - BINGO Roba široke potrošnje – osim prehrane Alije Izetbegovića 5 do 12 - COMMERCIAL Namještaj i bijela tehnika Alije Izetbegovića 134 do 12 - Shopping Card Trgovina na veliko i malo građevinskom COMMERCIAL Alije Izetbegovića 134 do 12 - opremom DM DROGERIE MARKT Kozmetika 119. Muslimanske brdske brigade 19 do 6 - OMEGA Bijela tehnika Husinske bune B-1 do 12 - PEKO Obuća Branilaca Banovića bb do 12 - UNIQA OSIGURANJE DD Osiguranje VII novembra 2 do 6 - GRAD DJELATNOST ADRESA BR. RATA POPUST Banja Luka A JEANS PODR. Butik Branka Popovića bb do 12 - ABC SPORTING Zlatara Aleja Svetog Save 69 do 12 - ABC SPORTING Zlatara Jovana akademika Surutke 3 do 12 - AB-LINE Odjeća Aleja Svetog Save 69 do 6 - AB-LINE Odjeća Trg Krajine 2 do 6 - AB-LINE TALLY WEIJL BL Odjeća Aleja Svetog Save 69 do 6 - AGRAMSERVIS Telekomunikacijska oprema i telefoni Kralja Petra Karađorđevića 7 do 12 - ALF-OM Prodaja i servis biroopreme Mladena Stojanovića 43 do 45 do 6 - Shopping Card ALMA-RAS Donje rublje Jevrejska 2 do 6 - ALMA-RAS Donje rublje Jovana Dučića 25 do 6 - ARDOR Namještaj Planinska bb do 12 - ARDOR Namještaj Vojvode Pere Krece 21 do 12 - ARTIST Muzički instrumenti Ivana Gorana Kovačića 203a do 12 - ASD Autodijelovi i servis vozila Bilečka bb do 12 - AUTOCENTAR MERKUR Prodaja automobilskih guma Knjaza Miloša bb do 6 - AUTO-MILOVANOVIĆ -

(In)Visible Traces: the Presence of the Recent Past in the Urban Landscape of Sarajevo

Рецензії. Огляди. Хроніка Natalia Otrishchenko Candidate of sociological sciences (PhD) Research fellow at the Center for Urban History of East Central Europe, L’viv (IN)VISIBLE TRACES: THE PRESENCE OF THE RECENT PAST IN THE URBAN LANDSCAPE OF SARAJEVO The author reflects on her observations during the summer school ‘History Takes Place – Dynamics of Urban Change.’ She discusses number of loca- tions, which embodied or recalled the memories of war and siege of the city, both those that remained from 1992-95 and those newly created. Based on the concept of the production of space, article outlines the specifics of inter- ventions into urban landscape with either monuments or alternative forms of commemoration. Key words: memory, monument, Sarajevo, siege, urban space. But we do not decide what to forget and what to remember. Ozren Kebo, Sarajevo for Beginners Sarajevo is a pure life. Kateryna Kalytko, Introduction to Sarajevo for Beginners Sarajevo: Briefly about the Context he gunshots near the Latin Bridge on 28 June 1914 started the Great War, and the shots on the Vrbanja Bridge on 5 April 1992 Tinaugurated the list of victims of the Siege of Sarajevo. The ‘short’ twentieth century started and finished on different bridges in the same city. Hence, war created one of the frames through which the history of Sarajevo might be perceived. Military conflicts over the last hundred years transformed both the social and material, as well as the symbolic, structures of the city and left a number of traces in its urban landscape. Fran Tonkiss states that there are cities overwhelmed with history, and Sarajevo is among them.