Rebuilding Sarajevo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

SARAJEVO WASTE WATER PROJECT Key Dates: Approved: December 22, 2009 Effective: July 15, 2010 Closing: November 30, 2015 Financing in million US Dollars:* Financier Financing Public Disclosure Authorized IBRD Loan 35.0 Government of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2.0 Total Project Cost 37.0 World Bank Disbursements, million US Dollars*: Total Disbursed Undisbursed IBRD Loan 35.0 1.19 33.73 * as of January, 2011. Note: Disbursements may differ from financing due to exchange rate fluctuations at the time of disbursement. Service delivery problems in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BH) are compounded by the lingering after-effects of the conflict Public Disclosure Authorized that left vast portions of basic infrastructure destroyed or severely damaged. A case that vividly illustrates the problem is waste water collection and treatment in the city of Sarajevo. A Waste Water Treatment Plant (WWTP) was built close to the confluence of the Miljacka and Bosna Rivers in the early 1980s on the occasion of the 1984 Winter Olympics. Construction of the plant was supported by the World Bank-financed Sarajevo Water Supply and Sewerage Project (Loan 1263-YU), which closed in December 1982. However, the plant was extensively damaged in the spring of 1992 at the outset of the conflict, during which the sewer network was also destroyed in various places. Since the end of the conflict in 1995, the WWTP has been largely out of commission with only minimal conservation works carried out to prevent further deterioration. As a result, virtually all of the city‟s waste water is discharged into the Miljacka and Bosna Rivers without any treatment, causing severe pollution of the rivers and impacting the communities downstream of the discharge point. -

SARAJEVO CANTON a PROFITABLE BUSINESS LOCATION Vodic08-EN2.Qxp:Layout 1 4/26/08 9:45 AM Page 2

Bosnia and Herzegovina Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarajevo Canton > A J N A V O L S O P G O N S O N U O T S E J M O V E J A R A S N O T N A K 8 0 0 2 V A J N A G A L U A N O I C I T S E V N I A Z Č I D O INVESTMENTS GUIDE 2008 SARAJEVO CANTON A PROFITABLE BUSINESS LOCATION > o v e j a r a S n o t n a K e n i v o g e c r e H i e n s o B a j i c a r e d e F a n i v o g e c r e H i a n s o B Vodic08-EN2.qxp:Layout 1 4/26/08 9:45 AM Page 1 Bosnia and Herzegovina / Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina SARAJEVO CANTON INVESTMENTS GUIDE 2008 SARAJEVO CANTON A PROFITABLE BUSINESS LOCATION Vodic08-EN2.qxp:Layout 1 4/26/08 9:45 AM Page 2 SARAJEVO CANTON 2008 2 A Profitable Business Location Investments Guide Development Planning Institute of the Sarajevo Canton Director: Said Jamaković, B.Sc. (Arch. ) Project Coordination: Traffic : Socio-Economic Development Planning Sector Almir Hercegovac, B.Sc.C.E. Hamdija Efendić, B.Sc.C.E. Maida Fetahagić M.Sc., Deputy Director Lejla Muhedinović, Technician Ljiljana Misirača, B.Sc.Ec., Head of Department of Development Funds Management and Coordination Geographic Information System: Gordana Memišević, B.Sc.Ec., Head of Department of Jasna Pleho, M.Sc. -

Nijaz Ibrulj Faculty of Philosophy University of Sarajevo BOSNIA PORPHYRIANA an OUTLINE of the DEVELOPMENT of LOGIC in BOSNIA AN

UDK 16 (497.6) Nijaz Ibrulj Faculty of philosophy University of Sarajevo BOSNIA PORPHYRIANA AN OUTLINE OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF LOGIC IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Abstract The text is a drought outlining the development of logic in Bosnia and Herzegovina through several periods of history: period of Ottoman occupation and administration of the Empire, period of Austro-Hungarian occupation and administration of the Monarchy, period of Communist regime and administration of the Socialist Republic and period from the aftermath of the aggression against the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina to this day (the Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina) and administration of the International Community. For each of the aforementioned periods, the text treats the organization of education, the educational paradigm of the model, status of logic as a subject in the educational system of a period, as well as the central figures dealing with the issue of logic (as researchers, lecturers, authors) and the key works written in each of the periods, outlining their main ideas. The work of a Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry, “Introduction” (Greek: Eijsagwgh;v Latin: Isagoge; Arabic: Īsāġūğī) , can be seen, in all periods of education in Bosnia and Herze - govina, as the main text, the principal textbook, as a motivation for logical thinking. That gave me the right to introduce the syntagm Bosnia Porphyriana. SURVEY 109 1. Introduction Man taman ṭaqa tazandaqa. He who practices logic becomes a heretic. 1 It would be impossible to elaborate the development of logic in Bosnia -

SARAJEVO in the WILDERNESS of POST- SOCIALIST TRANSITION: the NEOLIBERAL URBAN TRANSFORMATION of the CITY IS B N: 978 - 88 96951 23 1

PECOB’S VOLUMES N: 978 - 88 96951 23 1 B SARAJEVO IN THE WILDERNESS OF POST- SOCIALIST TRANSITION: THE NEOLIBERAL URBAN TRANSFORMATION OF THE CITY IS Cecilia Borrini European Regional Master’s Programme in Democracy and Human Rights in South East Europe GRADUATION THESIS Portal on Central Eastern and Balkan Europe University of Bologna - Forlì Campus www.pecob.eu SARAJEVO IN THE WILDERNESS OF POST- SOCIALIST TRANSITION: THE NEOLIBERAL URBAN TRANSFORMATION OF THE CITY Cecilia Borrini European Regional Master’s Programme in Democracy and Human Rights in South East Europe Graduation thesis Table of Contents Abstract ..................................................................................................... 7 Keywords ................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 1. Cities: Key Sites for the Economic Growth and Contestation ................ 13 1.1 A Lefebvrian Approach to the City: the Urban Claim for the Right to the City ................................................................................ 13 1.2 The Current Phase of Capitalism: Neoliberalism and Globalization ....................................................... 19 1.3 The Contemporary Revival of the Right to the City: A Claim against Neoliberalism ........................................................... 22 2. Urban development trends in Central and South Eastern Europe ......... 27 2.1 The Post-Socialist -

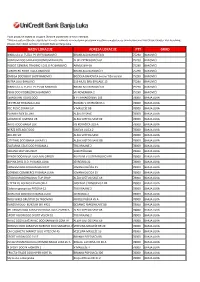

Spisak Za Kupovinu Na Rate

Popis prodajnih mjesta sa uslugom Obročne otplate bez kamata i naknada. *Plaćanje putem Obročne otplate bez kamata i naknada na navedenim prodajnim mjestima omogućeno je svim korisnicima Visa Classic Charge i Visa Revolving (Classic, Net i Gold) karticom UniCredit Bank ad Banja Luka. NAZIV LOKACIJE ADRESA LOKACIJE PTT GRAD BINGO d.o.o. TUZLA PJ 19 FIS BANOVIĆI BRANILACA BANOVIĆA B 75290 BANOVIĆI KONZUM DOO SARAJEVO KONZUM BIH K326 ALIJE IZETBEGOVIĆA 61 75290 BANOVIĆI ROBOT GENERAL TRADING CO D.O PC BANOVIĆI ARMIJE BIH 6A 75290 BANOVIĆI EUROHERC PODR TUZLA BANOVIĆI BRANILACA BANOVIĆI 4 75290 BANOVIĆI OMEGA DOO BEKO SHOP BANOVIĆI BOŽIĆKA BANOVIĆA 6-novi Tržni centar 75290 BANOVIĆI ASTRA DOO BANOVIĆI 119 MUSL BRD BRIGADE 15 75290 BANOVIĆI BINGO d.o.o. TUZLA PJ 23 SM BANOVIĆI BRANILACA BANOVIĆA B 75290 BANOVIĆI PEKO DOO PODRUŽNICA BANOVIĆI VII NOVEMBRA 2 75290 BANOVIĆI SEBASTIJAN TOURS DOO K P I KARAÐORÐEV 103 78000 BANJA LUKA CENTRUM TR BANJA LUKA BUDŽAK V.OSTROŠKOG 1 78000 BANJA LUKA KEC PUŠIĆ ZORAN S.P. V MASLEŠE BB 78000 BANJA LUKA PLANIKA FLEX B.LUKA ALEJA SV SAVE 78000 BANJA LUKA JAĆIMOVIĆ JUVENTA UR ALEJA SVETOG SAVE 69 78000 BANJA LUKA ARTIST DOO BANJA LUK I G KOVAČIĆA 203-A 78000 BANJA LUKA NERZZ BEŠLAGIĆ DOO GAJEVA ULICA 2 78000 BANJA LUKA AB LINE SIX ALEJA SVETOG SAVE 78000 BANJA LUKA CITYTIME DOO BANJA LUKA PJ 1 ALEJA SVETOG SAVE BB 78000 BANJA LUKA ZLATARNA CELJE DOO PJ BANJA L TRG KRAJINE 2 78000 BANJA LUKA VERANO MOTORS RENT SUBOTIČKA BB 78000 BANJA LUKA DEKOR DOO BANJA LUKA MALOPROD BULEVAR V S STEPANOVIĆA BB 78000 BANJA LUKA ALPINA BH D.O.O. -

Protection and Reuse of Industrial Heritage: Dilemmas, Problems, Examples

Monographic Publications of ICOMOS Slovenia of ICOMOS Publications Monographic Monographic Publication of ICOMOS Slovenia 02 Protection and Reuse of Industrial Heritage: Dilemmas, Problems, Examples ICOMOS Slovenia1 2 Monographic Publications of ICOMOS Slovenia I 02 Protection and Reuse of Industrial Heritage: Dilemmas, Problems, Examples edited by Sonja Ifko and Marko Stokin Publisher: ICOMOS SLovenija - Slovensko nacionalno združenje za spomenike in spomeniška območja Slovenian National Committee of ICOMOS /International Council on Monuments and Sites/ Editors: Sonja Ifko, Marko Stokin Design concept: Sonja Ifko Design and preprint: Januš Jerončič Print: electronic edition Ljubljana 2017 The publication presents selected papers of the 2nd International Symposium on Cultural Heritage and Legal Issues with the topic Protection and Reuse of Industrial Heritage: Dilemmas, Problems, Examples. Symposium was organized in October 2015 by ICOMOS Slovenia with the support of the Directorate General of Democracy/DG2/ Directorate of Democratic Governance, Culture and Diversity of the Council of Europe, Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia, Ministry of Culture of Republic Slovenia and TICCIH Slovenia. The opinions expressed in this book are the responsibility of the authors. All figures are owned by the authors if not indicated differently. Front page photo: Jesenice ironworks in 1938, Gornjesavski muzej Jesenice. CIP – Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Kataložni zapis o publikaciji (CIP) pripravili v Narodni in univerzitetni -

Beyond Your Dreams Beyond Your Dreams

Beyond your dreams Beyond your dreams Destınatıon BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA Bosnıa & Herzegovina Craggily beautiful Bosnia and Herzegovina is most intriguing for its East-meets-West atmosphere born of blended Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian histories. Many international visitors still associate the country with the heartbreaking civil war of the 1990s, and several attractions focus on the horrors of that era. But today, visitors will likely remember the country for its deep, unassuming human warmth, its beautiful mountain scapes and its numerous medieval castle ruins. Apart from modest Neum it lacks beach resorts, but easily compensates with cascading rafting rivers, waterfalls and bargain-value skiing in its mostly mountainous landscapes. Major drawcards are the reincarnated historic centres of Sarajevo and Mostar, counterpointing splendid Turkish-era stone architecture with quirky bars, inviting street- terrace cafes and a vibrant arts scene. And there's so much more to discover in the largely rural hinterland, all at prices that make the country one of Europes best-value destinations. Beyond your dreams How to get there? By plane Sarajevo Airport is in the suburb of Butmir and is relatively close to the city centre. There is no direct public transportation Some of the other airlines which operate regular (daily) services into Sarajevo By train Train services across the country are slowly improving once again, though speeds and frequencies are still low. Train services available to & from Crotia, Hungary and Serbia. By bus Buses are plentiful in and around Bosnia. Most international buses arrive at the main Sarajevo bus station (autobuska stanica) which is located next to the railway station close to the centre of Sarajevo. -

Godišnji Izvještaj Za 2016

EDUS- Godišnji izvještaj za 2016. GODIŠNJI 2016. IZVJEŠTAJ [NARATIVNI GODIŠNJI IZVJEŠTAJ] [Pregled najvažnijih aktivnosti, projekata i postignuća organizacije EDUS-Edukacija za sve u 2016. godini.] Mjedenica 34, 71000 Sarajevo [email protected] www.edusbih.org EDUS- Godišnji izvještaj za 2016. SADRŽAJ: 1. KRATAK PREGLED GLAVNIH DEŠAVANJA ..........................................................2 1.1. PRESJEK SVIH ŠEST GODINA EDUS-a.............................................................2 1.2. KRATAK PREGLED AKTIVNOSTI U 2016-oj ......................................................3 2. RAD S DJECOM PO NAUČNOJ METODOLOGIJI....................................................4 2.1. EDUS UČIONICE I VRTIĆKE GRUPE U OKVIRU ZAVODA MJEDENICA.....8 2.2. PROGRAM RANE INTERVENCIJE..................................................................9 2.3. DOPUNSKA NASTAVA..................................................................................10 2.4. LJETNA ŠKOLA..............................................................................................10 3. EDUKACIJA STRUČNJAKA.....................................................................................11 3.1. EDUKACIJA KROZ RAD U EDUS PROGRAMU............................................11 3.2. EDUKACIJA STRUČNJAKA ŠIROM BIH KROZ PROJEKAT S UNICEF-om I FEDERALNIM MINISTARSTVOM ZDRAVSTVA............................................11 3.3. TERCIJARNO OBRAZOVANJE EDUS-OVIH STRUČNJAKA U INOSTRANSTVU............................................................................................14 -

Neo-Liberalism, the Islamic Revival, and Urban Development in Post-War, Post-Socialist Sarajevo

Neo-Liberalism, the Islamic Revival, and Urban Development in Post-War, Post-Socialist Sarajevo By Zev Moses A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Geography Department of Geography and Program in Planning University of Toronto © Copyright by Zev Moses 2012 Neo-Liberalism, the Islamic Revival, and Urban Development in Post-War, Post-Socialist Sarajevo Zev Moses Master of Arts in Geography Department of Geography and Program in Planning University of Toronto 2012 Abstract This thesis examines the confluence between pan-Islamist politics, neo-liberalism and urban development in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. After tracing a history of the Islamic revival in Bosnia, I examine the results of neo-liberal policy in post-war Bosnia, particularly regarding the promises of neo-liberal institutions and think tanks that privatization and inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) would de-politicize the economy and strip ethno-religious nationalist elites of their power over state-owned firms. By analyzing three prominent new urban developments in Sarajevo, all financed by FDI from the Islamic world and brought about by the privatization of urban real-estate, I show how neo-liberal policy has had unintended outcomes in Sarajevo that contradict the assertions of policy makers. In examining urban change, I bring out the role played by the city in mediating between both elites and citizens, and between the seemingly contradictory projects of pan-Islamism and neo- liberalism. ii Acknowledgements I would like to extend my gratitude to everyone who helped me in one way or another with this project. -

Remaking History: Tracing Politics in Urban Space

Remaking History: Tracing Politics in Urban Space Lejla Odobašić Novo & Aleksandar Obradović International Burch University Sarajevo 2021 Authors: Lejla Odobašić Novo & Aleksandar Obradović Publishing: International Burch University Critcal Review: Nerma Prnjavorac Cridge & Vladimir Dulović Proofreading: Adrian Pecotić Project Logo Design: Mina Stanimirović Book Layout Mina Stanimirović & Lejla Odobašić Novo EBook (URL): http://remakinghistory.philopolitics.org/index.html Date and Place: February 2021, Sarajevo Copyrights: International Burch University & Philopolitics Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without permission from the copyright holder. Repro- duction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Disclaimer: While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information contained in this publication, the publisher will not assume liability for writing and any use made of the proceedings, and the presentation of the participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territo- ry, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. CIP zapis je dostupan u elektronskom katalogu Nacionalne i univerzitetske biblioteke Bosne i Hercegovine pod brojem COBISS.BH-ID 42832902 ISBN 978-9958-834-67-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE Critical Review by Nerma Prnjavorac Cridge... ..................1 Critical Review by Vladimir Dulović ................. -

Geopolitical and Urban Changes in Sarajevo (1995 – 2015)

Geopolitical and urban changes in Sarajevo (1995 – 2015) Jordi Martín i Díaz Aquesta tesi doctoral està subjecta a la llicència Reconeixement- NoComercial – SenseObraDerivada 3.0. Espanya de Creative Commons. Esta tesis doctoral está sujeta a la licencia Reconocimiento - NoComercial – SinObraDerivada 3.0. España de Creative Commons. This doctoral thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0. Spain License. Facultat de Geografia i Història Departament de Geografia Programa de Doctorat “Geografia, planificació territorial i gestió ambiental” Tesi doctoral Geopolitical and urban changes in Sarajevo (1995 – 2015) del candidat a optar al Títol de Doctor en Geografia, Planificació Territorial i Gestió Ambiental Jordi Martín i Díaz Directors Dr. Carles Carreras i Verdaguer Dr. Nihad Čengi ć Tutor Dr. Carles Carreras i Verdaguer Barcelona, 2017 This dissertation has been funded by the Program Formación del Profesorado Universitario of the Spanish Ministry of Education, fellowship reference (AP2010- 3873). Als meus pares i al meu germà. Table of contents Aknowledgments Abstract About this project 1. Theoretical and conceptual approach 15 Socialist and post-socialist cities 19 The question of ethno-territorialities 26 Regarding international intervention in post-war contexts 30 Methodological approach 37 Information gathering and techniques 40 Structure of the dissertation 44 2. The destruction and division of Sarajevo 45 Sarajevo: common life and urban expansion until early 1990s 45 The urban expansion 48 The emergence of political pluralism 55 Towards the ethnic division of Sarajevo: SDS’s ethno-territorialisation campaign and the international partiality in the crisis 63 The Western policy towards Yugoslavia: paving the way for the violent ethnic division of Bosnia 73 The siege of Sarajevo 77 Deprivation, physical destruction and displacement 82 The international response to the siege 85 SDA performance 88 Sarajevo’s ethno-territorial division in the Dayton Peace Agreement 92 The DPA and the OHR’s mission 95 3. -

This Is How It All Began... Learn More About the Centre Of

Centre of Cultivating Dialogue 1997 – 2016 THIS IS HOW IT ALL BEGAN... Back in 1997, a handful of enthusiasts initiated a program one hardly could have predicted for bright future considering the political, economic and educational situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Differences and divisions in the country were much more pronounced than today, which was especially noticed in educational program. However, sixteen years later the program can boast with a number of activities and participants to be envied by many, even most respected international programs. The first teachers to be involved in the program could not have even imagined they would be a part of the team that would participate in activities like seminars, meetings, round table discussions, and summer camps, debate activities in schools, TV debates, and world championships. Even less could they imagine that these activities would become a matter of tradition, one that future generations can look up to and admire. Since then more than 350 high school teachers from 75 Bosnian towns were educated through, on average, somewhat less than 150 activities per year. The program itself was obviously not created for teachers, but first and foremost for the benefit of young people in BiH. The goal has been to educate and train young people in debating skills and consequently in democracy and tolerance, which can be applied daily. This is Centre of Cultivating Dialogue, a program which sets debate as a contemporary method of education, through direct cooperation of all participants and constant rhetoric, cross examination, argumentation, research exercises… The total number of people involved in the aforementioned activities has grown to 33.000 and all of them have at least some experience they use today.