1 1 Chapter I the Development and History of the Theory of Dacian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romanian Language and Its Dialects

Social Sciences ROMANIAN LANGUAGE AND ITS DIALECTS Ana-Maria DUDĂU1 ABSTRACT: THE ROMANIAN LANGUAGE, THE CONTINUANCE OF THE LATIN LANGUAGE SPOKEN IN THE EASTERN PARTS OF THE FORMER ROMAN EMPIRE, COMES WITH ITS FOUR DIALECTS: DACO- ROMANIAN, AROMANIAN, MEGLENO-ROMANIAN AND ISTRO-ROMANIAN TO COMPLETE THE EUROPEAN LINGUISTIC PALETTE. THE ROMANIAN LINGUISTS HAVE ALWAYS SHOWN A PERMANENT CONCERN FOR BOTH THE IDENTITY AND THE STATUS OF THE ROMANIAN LANGUAGE AND ITS DIALECTS, THUS SUPPORTING THE EXISTENCE OF THE ETHNIC, LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL PARTICULARITIES OF THE MINORITIES AND REJECTING, FIRMLY, ANY ATTEMPT TO ASSIMILATE THEM BY FORCE KEYWORDS: MULTILINGUALISM, DIALECT, ASSIMILATION, OFFICIAL LANGUAGE, SPOKEN LANGUAGE. The Romanian language - the only Romance language in Eastern Europe - is an "island" of Latinity in a mainly "Slavic sea" - including its dialects from the south of the Danube – Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian and Istro-Romanian. Multilingualism is defined narrowly as the alternative use of several languages; widely, it is use of several alternative language systems, regardless of their status: different languages, dialects of the same language or even varieties of the same idiom, being a natural consequence of linguistic contact. Multilingualism is an Europe value and a shared commitment, with particular importance for initial education, lifelong learning, employment, justice, freedom and security. Romanian language, with its four dialects - Daco-Romanian, Aromanian, Megleno- Romanian and Istro-Romanian – is the continuance of the Latin language spoken in the eastern parts of the former Roman Empire. Together with the Dalmatian language (now extinct) and central and southern Italian dialects, is part of the Apenino-Balkan group of Romance languages, different from theAlpine–Pyrenean group2. -

Elements of Romanian Spirituality in the Balkans – Aromanian Magazines and Almanacs (1880-1914)

SECTION: JOURNALISM LDMD I ELEMENTS OF ROMANIAN SPIRITUALITY IN THE BALKANS – AROMANIAN MAGAZINES AND ALMANACS (1880-1914) Stoica LASCU, Associate Professor, PhD, ”Ovidius” University of Constanța Abstract: Integral parts of the Balkan Romanian spirituality in the modern age, Aromanian magazines and almanacs are priceless sources for historians and linguists. They clearly shape the Balkan dimension of Romanism until the break of World War I, and present facts, events, attitudes, and representative Balkan Vlachs, who expressed themselves as Balkan Romanians, as proponents of Balkan Romanianism. Frăţilia intru dreptate [“The Brotherhood for Justice”]. Bucharest: 1880, the first Aromanian magazine; Macedonia. Bucharest: 1888 and 1889, the earliest Aromanian literary magazine, subtitled Revista românilor din Peninsula Balcanică [“The Magazine of the Romanians from the Balkan Peninsula”]; Revista Pindul (“The Pindus Magazine”). Bucharest: 1898-1899, subtitled Tu limba aromânească [“In Aromanian Language”]; Frăţilia [“The Brotherhood”]. Bitolia- Buchaerst: 1901-1903, the first Aromanian magazine in European Turkey was published by intellectuals living and working in Macedonia; Lumina [“The Light”]: Monastir/Bitolia- Bucharest: 1903-1908, the most long-standing Aromanian magazine, edited in Macedonia, at Monastir (Bitolia), in Romanian, although some literary creations were written in the Aromanian dialect, and subtitled Revista populară a românilor din Imperiul Otoman (“The People’s Magazine for Romanians in the Ottoman Empire”) and Revista poporană a românilor din dreapta Dunărei [“The People’s Magazine of the Romanians on the Right Side of the Danube”]; Grai bun [“Good Language”]. Bucharest, 1906-1907, subtitled Revistă aromânească [Aromanian Magazine]; Viaţa albano-română [“The Albano-Romaninan Life”]. Bucharest: 1909-1910; Lilicea Pindului [“The Pindus’s Flower”]. -

Aromânii: Sub Semnul Risipirii?

ACTA IASSYENSIA COMPARATIONIS 3/2005 NIKOLA VANGELI (student) Universitatea „Kiril i Metodij” Skopje Aromânii: sub semnul risipirii? Când este vorba de cultura şi civilizaţia unui popor, datele istorice reprezintă un cadru necesar (nu şi suficient). Scrisă sau rostită, istoria se referă la timpul trecut. Ea fixează şi dă formă realităţii, ajutînd-o să devină obiect de studiu. Cultura aromână este, în primul rând, o cultură orală. Primele sale scrieri istorice datează abia din secolul al XIX-lea. Se poate trage, oare, concluzia că aromânii sunt un popor fără istorie? În genere, „cu/fără istorie” este echivalent cu „a avea/a nu avea istorie scrisă”. Avantajul istoriei scrise este că prezintă urme palpabile, vizibile, ale trecutului. Şi istoria orală lasă urme, dar acestea sunt ascunse; trebuie să fim bine pregătiţi şi foarte atenţi ca să le putem descoperi. Istoria scrisă apare o dată cu întemeierea aşezărilor urbane şi se referă la un teritoriu bine precizat. În această perspectivă, dezinteresul aromânilor pentru istoria scrisă pare să aibă o explicaţie: nu şi-au scris istoria pentru că niciodată nu au avut o ţară a lor proprie, un teritoriu bine delimitat, de care să aparţină – cu toate că mereu s-au considerat români, iar limba şi-au considerat-o un grai desprins din trunchiul comun din care s-a dezvoltat şi limba română1. Numeroase izvoare scrise din ţările Peninsulei Balcanice îi pomenesc pe aromâni, dar totdeauna scriu cu mare rezervă despre ei şi le dau foarte puţină importanţă. Pe aromâni îi menţionează cronicarii bizantini (Nicetas Choniates; Pakymeres; Laonikos Chalkokondylas), cronicarii francezi (Geoffroi de Villehardouin; Henry de Valenciennes), cronicarul catalan Ramon Muntaner, călători din timpuri mai vechi şi mai noi (Benjamin de Tudela; Pierre Belon du Mans; Pouqueville – fost consul al lui Napoleon Bonaparte pe lângă Ali Paşa din Ianina; colonelul William Martin-Leake), savanţi (Alan J. -

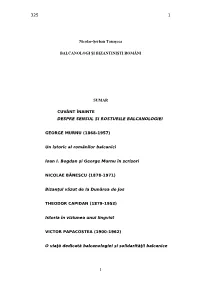

|N Loc De Prefa}+

325 1 Nicolae-Şerban Tanaşoca BALCANOLOGI ŞI BIZANTINIŞTI ROMÂNI SUMAR CUVÂNT ÎNAINTE DESPRE SENSUL ŞI ROSTURILE BALCANOLOGIEI GEORGE MURNU (1868-1957) Un istoric al românilor balcanici Ioan I. Bogdan şi George Murnu în scrisori NICOLAE BĂ NESCU (1878-1971) Bizanţ ul v ă zut de la Dun ă rea de Jos THEODOR CAPIDAN (1879-1953) Istoria în viziunea unui lingvist VICTOR PAPACOSTEA (1900-1962) O viaţă dedicat ă balcanologiei şi solidarit ăţ ii balcanice 1 325 2 CUVÂNT ÎNAINTE DESPRE SENSUL ŞI ROSTURILE BALCANOLOGIEI 2 325 3 Balcanologia, ştiinţ a dedicat ă cunoaşterii Peninsulei Balcanice ∗ sau Sud-Est Europene , poate fi definită ca studiul sistematic, comparat şi interdisciplinar al lumii balcanice sau sud-est europene, sub aspectul unităţ ii ei în diversitate. Ea este rodul unei îndelungate evoluţ ii a studiilor de geografie, istorie, etnografie şi lingvistic ă balcanică , practicate atât în Europa occidental ă , cât şi în lumea balcanică îns ă şi. Bizantinistul grec Dionysios Zakythinos, care i-a schiţ at, în 1970, istoria, a ar ă tat ce anume datoreaz ă aceast ă complexă disciplin ă ştiin ţ ific ă treptatei redescoperiri a lumii balcanice de că tre înv ăţ a ţ ii europeni, pe m ă sura expansiunii civiliza ţ iei occidentale că tre R ă s ă rit şi ce anume n ă zuin ţ ei popoarelor balcanice de a-şi regă si şi reafirma identitatea, ca na ţ iuni libere, în procesul emancipă rii lor de sub domina ţ ia otoman ă . În Introducerea programatică a revistei interna ţ ionale ”Balcania”, un text mai curând uitat astă zi, ca şi în alte pagini teoretice, istoricul român Victor Papacostea a fă cut cea mai complet ă şi mai clar ă expunere a principiilor, metodelor şi obiectivelor balcanologiei. -

Arhive Personale Şi Familiale

Arhive personale şi familiale Vol. II Repertoriu arhivistic Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei ISBN 973-8308-08-9 Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei ARHIVELE NAŢIONALE ALE ROMÂNIEI Arhive personale şi familiale Vol. II Repertoriu arhivistic Autor: Filofteia Rînziş Bucureşti 2002 Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei ● Redactor: Alexandra Ioana Negreanu ● Indici de arhive, antroponimic, toponimic: Florica Bucur ● Culegere computerizată: Filofteia Rînziş ● Tehnoredactare şi corectură: Nicoleta Borcea ● Coperta: Filofteia Rînziş, Steliana Dănăilescu ● Coperta 1: Scrisori: Nicolae Labiş către Sterescu, 3 sept.1953; André Malraux către Jean Ajalbert, <1923>; Augustin Bunea, 1 iulie 1909; Alexandre Dumas, fiul, către un prieten. ● Coperta 4: Elena Văcărescu, Titu Maiorescu şi actriţa clujeană Maria Cupcea Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei CUPRINS Introducere ...................................................................... 7 Lista abrevierilor ............................................................ 22 Arhive personale şi familiale .......................................... 23 Bibliografie ...................................................................... 275 Indice de arhive ............................................................... 279 Indice antroponimic ........................................................ 290 Indice toponimic............................................................... 339 Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei INTRODUCERE Cel de al II-lea volum al lucrării Arhive personale şi familiale -

Discursul Istoric Între Realitate Şi Ficţiune. Complementarităţi Şi Antinomii

Discursul istoric între realitate şi ficţiune. Complementarităţi şi antinomii NARRATING NATIONAL UTOPIA. THE CASE OF MOSCHOPOLIS IN THE AROMANIAN NATIONAL DISCOURSE Steliu Lambru Utopias have unfolded primarily as chosen places by the human mind to fulfil the desire of daydreaming to the perfect world and to keep hoping for a new and best human society. Academically, this type of imagining a new world trespassed its initial purpose and became an object of analysis as a distinct field in humanities, especially as a clear literary genre. From a larger range of the utopian varieties (like distopias/ black utopias/ anti-utopias, regressive utopias, or reli- gious utopias/ chiliasms),1 I shall analyse that particular type of one’s utopian way of living, namely, the national utopia which, as the most common utopian discourse has never been separated from psychological human aspirations, cannot be circumscribed outside authors’ period in which he lived in. The highest aim of any utopia was to reach harmony or order; around these ideals, it also emerged the type of the national regressive utopia. As its original archetype, the national regressive utopia seeks to arrange human society as an isolated place in which individuals live perfectly with other individuals and environment.2 Most usual explanations for the indefatigable endeavour of utopian discourse to compose a parallel milieu for human beings claimed that this feeling has its roots in a deeply strong desire to overcome all unfulfilled bad things from one’s ordinary life and has a deep relationship with one’s feelings and attitudes toward the material surrounding world. -

Peter Atanasov, 1 Republica Macedonia

memoria ethnologica nr. 52 - 53 * iulie - decembrie 2014 ( An XIV ) PETER ATANASOV, 1 REPUBLICA MACEDONIA Cuvinte cheie: megleno-români, dialectul megleno-român, bilingvism, căsătorii mixte, extincţia limbii Starea actuală a meglenoromânilor. Meglenoromâna – un idiom pe cale de dispariţie Rezumat În articolul de faţă, autorul descrie cu îngrijorare situaţia actuală a meglenoromânei, unul din cele trei dialecte istorice sud-dunărene ale românei. Meglenoromâna, ca istroromâna, de altfel, este o mică enclavă lingvistică puternic influenţată de limbile cu care a venit în contact de-a lungul secolelor. Acest contact a dus la existenţa unui bilingvism secular care, la rândul lui, a favorizat o puternică influenţă în toate compartimentele dialectului meglenoromân. Dislocarea unei mari părţi a populaţiei (stabilirea în Turcia sau în România), exodul din mediul rural spre cel urban, căsătoriile mixte, lipsa învăţământului în limba română şi multe alte cauze vor duce la dispariţia iminentă a dialectului meglenoromân într-un viitor apropiat. 1 University in Skopje, Republic of Macedonia 30 memoria ethnologica nr. 52 - 53 * iulie - decembrie 2014 ( An XIV ) Key words: Megleno-Romanians, Megleno-Romanian dialect, bilingualism, intermar - riages, language extinction The Current State of Megleno-Romanians. Megleno-Romanian, an Endangered Idiom Summary In his essay, the author focuses on the current situation of Megleno- Romanian, one of the three historical South-Danubian dialects of Romanian. Megleno-Romanian, similarly with Istro-Romanian, is a small linguistic enclave, strongly influenced by other languages it came into contact with during the last centuries. This long-lasting contact strongly influenced all segments of the Megleno-Romanian dialect and led to a century-old bilingualism. -

Historiographical Disputes About the Aromanian Problem (19Th-20Th Centuries)

EMANUIL INEOAN1 HISTORIOGRAPHICAL DISPUTES ABOUT THE AROMANIAN PROBLEM (19TH-20TH CENTURIES) Abstract: The presence of Aromanians in the Balkans has sparked numerous controversies about their autochthonous character or the origins of their spoken idiom. Their identity as a Romance people has been challenged, on countless occasions, by more or less biased researchers. The emergence of the Megali Idea project of the modern Greek State has exerted a considerable impact on the group of Balkan Aromanians, as attempts have been made to integrate them into the Hellenic national grand narrative. Our study aims to inventory and analyse some of the reflections encountered in the Balkan historiographies from the second half of the 19th century until the dawn of the 21st century. Keywords: Aromanians, ethnogenesis, language, Greece, controversy * Far from proposing a definitive elucidation of one of the most intriguing ethnic questions of the Balkans - the origins of the Aromanians -, this study provides an introduction into this issue through an inventory of the main interpretations produced in the Greek, Romanian, Serbian, Bulgarian and Albanian historiographies relating to the subjects of our study. Today most historians agree that the Romanian people was formed on a territory that stretched both north and south of the Danube, a territory that obviously went far beyond the present-day borders of Romania. From a single common trunk, the branches that subsequently got separated included the Daco-Romanians, forming the so-called North Danubian Romanianness, and the Aromanians, the Megleno- Romanians and the Istro-Romanians, forming South Danubian Romanianness. The three groups constitute, to this day, the testimony of Eastern Romanness in a part of Europe that underwent radical changes over time, which modified almost entirely the Roman legacy in the area. -

Ethno-Confessional Realities in the Romanian Area: Historical Perspectives (XVIII-XX Centuries)

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Ethno-Confessional Realities in the Romanian Area: Historical Perspectives (XVIII-XX centuries) Brie, Mircea and Şipoş, Sorin and Horga, Ioan University of Oradea, Romania 2011 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/44026/ MPRA Paper No. 44026, posted 30 Jan 2013 09:17 UTC ETHNO-CONFESSIONAL REALITIES IN THE ROMANIAN AREA: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES (XVIII-XX CENTURIES) ETHNO-CONFESSIONAL REALITIES IN THE ROMANIAN AREA: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES (XVIII-XX CENTURIES) Mircea BRIE Sorin ŞIPOŞ Ioan HORGA (Coordinators) Foreword by Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU Oradea 2011 This present volume contains the papers of the international conference Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union’s East Border (workshop: Ethno-Confessional Realities in the Romanian Area: Historical Perspectives), held in Oradea between 2nd-5th of June 2011. This international conference, organized by Institute for Euroregional Studies Oradea-Debrecen, University of Oradea and Department of International Relations and European Studies, with the support of the European Commission and Bihor County Council, was an event run within the project of Action Jean Monnet Programme of the European Commission n. 176197-LLP-1- 2010-1-RO-AJM-MO CONTENTS Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU Foreword ................................................................................................................ 7 CONFESSION AND CONFESSIONAL MINORITIES Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU Confessionalisation and Community Sociability (Transylvania, 18th Century – First Half of the -

Meglenoromânii – Între Aculturaţie Şi Dispariţie Etnică

COMUNITĂŢI ROMÂNEŞTI ŞI IDENTITATE ETNICĂ COMUNITĂŢI CARE SE STING: MEGLENOROMÂNII – ÎNTRE ACULTURAŢIE ŞI DISPARIŢIE ETNICĂ EMIL ŢÎRCOMNICU* ABSTRACT COMMUNITIES ON THE VERGE OF EXTINCTION: MEGLENOROMANIANS – BETWEEN ACCULTURATION AND ETHNIC DISSOLUTION Among Romanian historical communities, two are currently close to ethnic and linguistic assimilation, due to their small number of members, the impossibility of claiming their cultural and linguistic rights, as well as the refusal of Balkan states to protect them. These groups are the Meglenoromanians and Istroromanians. In this study, we make a historical and ethnographic analysis of the small Meglenoromanian community, which was united until the Balkan wars, was split in two through the division of the Meglen land between Greece and the Serbian-Croatian-Slovenian Kingdom (1913), and then split again into two groups through the expulsion of Muslim Meglenoromanians to Turkey (1921) and the colonization of over 2 000 persons from Romania (in the Quadrilater, beginning in 1925, and afterwards in Cerna village, Tulcea county, in 1940). Keywords: Meglenoromanians, Romanian minorities, the Balkans, ethnogenesis, the Meglen region. 1. INTRODUCERE Astăzi, situaţia comunităţilor istorice româneşti autohtone în spaţiul balcanic este tragică. Încet, încet, dialectele limbii române se sting. Istroromâna mai este vorbită de o comunitate care nu numără mai mult de 2 000 de persoane. Meglenoromâna este într-o situaţie asemănătoare. Aromâna se află într-o situaţie mai bună, fiind vorbită ca limbă maternă de aproximativ 100 000 de persoane. Singurul stat, dintre cele în care aromânii sunt autohtoni, care promovează politici conforme Recomandării 1333 a APCE din 1997 este R. Macedonia. În privinţa istroromânei, la iniţiativa deputatului european Vlad Cubreacov, s-a realizat o monitorizare concretizată într-un Raport public al Comitetului de Experţi ai Consiliului * Address correspondence to Emil Ţîrcomnicu: Institutul de Etnografie şi Folclor „C. -

Marian TUTUI, Romanian Film Archive BALKAN CINEMA

Marian TUTUI, Romanian Film Archive BALKAN CINEMA VERSUS CINEMA OF THE BALKAN NATIONS 2. Manakia Bros: Pioneers of Balkan Cinema, Claimed by Six Nations In Romania’s capital we found out that in France and England they sell cameras rendering “living” photos. Ienache already could not get rid of the desire to return to Bitola with a shooting camera. Even in his sleep was longing for it. While I returned home, he went to London where he purchased a Bioscope camera. Milton Manakia The Vlach (Aromanian) brothers Ienache and Miltiade Manakia represent the most eloquent example of filmmakers that belong to the Balkan cultural heritage as the attempt to establish their affiliation to one or another national cinema is foredoomed to failure. They are considered as the first Balkan filmmakers as they had shot several important films for no less than six Balkan nations. Also for the impressive number of photos they made and mainly for their importance they remain as the most important photographers in the Balkans. Ienache had a photographic activity of at least 41 years while Milton of 65 years, quite impossible to match with. They also shot films between 1907- 1912 and owned an open cinema and a cinema theatre between 1921- 1939. Unfortunately their work is almost unknown in Romania and although they considered themselves as Romanians, Yugoslavia, Greece, R.Macedonia, Turkey and Albania have been claiming them in the last decades. Ienache (Ion, Ianakis), the elder brother (1878-1954) and Milton (Miltiade), the younger one (1882- 1964), were born in nowadays Northern Greece at Avdella in the Pindus Mountains, a region that until 1912 was part of the Ottoman Empire. -

Prominent Romanian Figures on the Aromanian Issue (Late Nineteenth – Early Twentieth Centuries)

PROMINENT ROMANIAN FIGURES ON THE AROMANIAN ISSUE (LATE NINETEENTH – EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES) STOICA LASCU* The question of the Balkan Romanians concerned almost all the prominent cultural and political figures in the Old Kingdom. Politicians (including King Carol I), scholars, journalists and publishers underlined the common origin of the Balkan Romanians (Aromanians and Megleno-Romanians) and North-Danubian Romanians. They stressed the necessity for sustained and efficient action on behalf of the Romanian State to dimension – through exclusively cultural means, first of all by opening Romanian schools in the Balkan parts of the Ottoman Empire – Balkan Romanianism as such. They expressed, through numerous articles and public assemblies, their solidarity with the effort of the Aromanians and Megleno- Romanians to maintain their own Romanian ethnic and linguistic identity. Keywords: Balkan Romanians; Aromanian issue; King Carol I; Dumitru Brătianu; Petre P. Carp; Take Ionescu; Constantin Mille; Romania; Macedonia The question of the Balkan Romanians was a preoccupation of almost all the important cultural and political figures of the Old Kingdom. “There is no state in Eastern Europe, no country from the Adriatic to the Black Sea that doesn’t include some fraction of our nationality. From the shepherds of Istria to those of Bosnia and Herzegovina, we find step by step fragments of this large ethnical unity in the Albanian mountains, in Macedonia and Thessaly, in the Pindus, and also in the Balkans, in Serbia, in Bulgaria, from Greece to the Dniester, near Odessa and Kiev,” wrote Mihai Eminescu in Timpul on 26 October 1878.1 The national poet would often return to the Balkan Romanians’ question,2 his interest “in the historical past, its contemporary state and the future perspectives of the Romanian spirit in the Balkans being constant and passionate.”3 * “Ovidius” University, Constanţa, Romania; [email protected], [email protected].