The Effects of Radical Groups on the Labor Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Youngstown State University Oral History Program

YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM 1952 Youngstown Sheet & Tube Steel Strike Personal Experience O.H. 1218 RUSSELL L. THOMAS Interviewed by Andrew Russ on October 28, 1988 Russell Thomas resides in North Jackson, Ohio and was born on January 18, 1908 in East Palestine, Ohio. He attended high school in Coitsville, Ohio and eventually was employed for the United Steel Workers of America in the capacity of local union representative. Tn this capacity, he worked closely with the Youngstown's local steel workers' unions. It was from this position that he experienced the steel strike of 1952. Mr. Thomas, after relating his biography, went on to discuss the organization of the Youngstown contingent of the United Steel Workers of America. He went into depth into the union's genera- tion, it's struggle with management, and the rights it obtained for the average worker employed in the various steel mills of Youngstown. He recollected that the steel strike of 1952 was one that was different in the respect that President Truman had taken over the operation of the mills in order to prosecute the Korean War effort. He also discussed local labor politics as he had run for the posiUon of local union president. Although he was unsuccessful in this bid for office, his account of just how the local labor political game was played provided great insight into the labor movement's influence upon economic issues and public opinion. His interview was different in that it discussed not only particular issues that affected the average Youngstown worker employed in steel, but also broad political and economic ones that molded this period of American labor history. -

Experiences of C.W. Editor in Steel Towns with C.I.O

Experiences of C.W. Editor in Steel Towns with C.I.O. Dorothy Day The Catholic Worker, August 1936, 1, 2. *Summary: Impressions from a fact-finding tour of Pennsylvania steel towns and interviews with such figures as Bishop Boyle of Pittsburgh; John L. Lewis, chairman of the CIO; Kathryn Lewis, his daughter; and John Brophy, Director of the CIO. For readers seeking background information on the steel/labor struggle, she recommends several books. Applauds church and government efforts to support labor in its struggle to organize and notes with satisfaction The CW ’s ability to transcend race and ethnic boundaries. Keywords: labor, unions, social teaching (DDLW #302).* A story like this is too big to compress in one column. Impressions crowded upon one over two weeks of constant observation are hard to put down on paper. There could be an interview with Bishop Boyle of Pittsburgh; with John L. Lewis, chairman of the Committee on Industrial Organization; with John Brophy, director of the committee; with Philip Murray, head of the Steel Workers’ Organization Committee (SWOC); with Pat Fagin, president of District No. 5 of the United Mine Workers; with the wives and mothers of steel workers; with Father Kazincy, who spoke from a wooden platform out in an open air mass meeting at Braddock last Sunday; with Smiley Chatak, the young organizer of the Allegheny Valley; with the Slovaks, the Croatians, the Syrians, the Italians and the Americans I have been seeing this past month–individuals among the 500,000 steel workers who have been unorganized, oppressed and enslaved for the last half century in the giant mills of the American Iron and Steel Institute. -

The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 Bargaining for Security: The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960 Henry Edward Himes III [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Labor History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Himes, Henry Edward III, "Bargaining for Security: The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3917. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3917 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bargaining for Security: The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960 Henry E. Himes III Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Ken Fones-Wolf, PhD., Chair Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, PhD. -

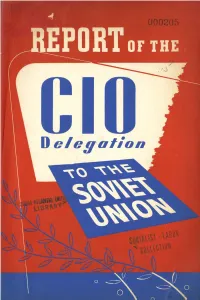

Soviet Union

REPORT of the CIO DELEGATION to the SOVIET UNION Submitted by JAMES B. CAREY Secretary-Treasurer, CIO Chairman of the Delegation Other Members of the Delegation: JOSEPH CURRAN REID ROBINSON rice-President, CIO Fice-P resident , CIO President, N at ional M arit ime Union President , Lnt crnational Union of .lIint', J / ill and Smelt er Il'orkers ALBERTJ . FITZGERALD r ice-Pre siden t, CIO LEE PRESSMAN President , Un ited E lect rical, R adio and General Couusrl, c/o JIacliine W orkers 0/ .Inisr ica JOHN GREEN JOHN ABT rice-President, CIO General Cou nsel, Amalgamat ed Clot hing President, Indust rial Union 0/ M an ne and W orku 5 0/ .lmeri ca Sh ipb uilding W orlecrs LEN DE CAUX ALLAN S. HAYWOOD Pu blicit y D irect or, CIO, and E dit or, Tilt' Fice -President, CIO C/O N m 's D irector 0/ Organization, CIO EMIL RIEVE VINCENT SWEENEY r ia-President, CIO Pu blicit y D irect or, United St rrlzcorlerrs President, T ext ile W orkers Union oi A merica 0/ A merica; Editor, St eel Labor Publication No. 128 Price 15c per copy; 100 for $10.00; 500 for $40.00 D epartment of International Affairs Order Literature from Publicity Department CONGRESS OF INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATIONS 718 JACKSON PLACE, N. W. WASHINGTON 6, D. C. \ -- . ~ 2 rr To Promote Friendship And Understanding... " H E victo ry of the United Nations over the military power of fascism T opened up prospects of a new era of int ern ational understanding, democratic progress, world peace and prosperity. -

The Little Steel Strike of 1937

This dissertation has been Mic 61-2851 microfilmed exactly as received SOFCHALK, Donald Gene. THE LITTLE STEEL STRIKE OF 1937. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1961 History, modem ; n University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE LITTLE STEEL STRIKE OF 1937 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Donald Gene Sofchalk, B. A., M. A. ***** The Ohio State University 1961 Approved by Adviser Department of History PREFACE On Sunday, May 30, 1937, a crowd of strikers and sympathizers marched toward the South Chicago plant of the Republic Steel Corpora tion. The strikers came abreast a line of two hundred Chicago police, a scuffle ensued, and the police opened fire with tear gas and revolvers. Within minutes, ten people were dead or critically injured and scores wounded. This sanguinary incident, which came to be known as the "Memorial Day Massacre," grew out of a strike called by the Steel Workers Or&soizing Committee of the CIO against the so-called Little Steel companies. Two months previously the U. S. Steel Corporation, traditional "citadel of the open shop," had come to terms with SWOC, but several independent steel firms had refused to recognize the new union. Nego tiations, never really under way, had broken down, and SWOC had issued a strike call affecting about eighty thousand workers in the plants of Republic, Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company, and Inland Steel Company in six states. The Memorial Day clash, occurring only a few days after the * strike began, epitomized and undoubtedly intensified the atmosphere of mutual hostility which characterized the strike. -

First to the Party: the Group Origins of the Partisan Transformation on Civil Rights, 1940–1960

Studies in American Political Development, 27 (October 2013), 1–31. ISSN 0898-588X/13 doi:10.1017/S0898588X13000072 # Cambridge University Press 2013 First to the Party: The Group Origins of the Partisan Transformation on Civil Rights, 1940–1960 Christopher A. Baylor, College of the Holy Cross One of the most momentous shifts in twentieth-century party politics was the Democratic Party’s embrace of civil rights. Recent scholarship finds that this realignment began as early as the 1940s and traces it to pressure groups, especially organized labor. But such scholarship does not explain why labor, which was traditionally hostile to African Americans, began to work with them. Nor does it ascribe agency to the efforts of African American pressure groups. Focusing on the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), this article attempts to fill these gaps in the literature. It explains why civil rights and labor leaders reassessed their traditional animosities and began to work as allies in the Democratic Party. It further shows how pressure from the new black-blue alliance forced the national Democratic Party to stop straddling civil rights issues and to become instead the vehicle for promoting civil rights. NAACP and CIO leaders consciously sought to remake the Democratic Party by marginalizing conservative Southerners, and eventually succeeded. The partisan transformation on civil rights is arguably became the party of states’ rights. The civil rights the most important twentieth-century case in Ameri- transformation arguably presaged the future partisan can politics in which parties changed positions on division on cultural issues as well. -

The 1952 Steel Seizure Revisited: a Systematic Study in Presidential Decision Making Author(S): Chong-Do Hah and Robert M

The 1952 Steel Seizure Revisited: A Systematic Study in Presidential Decision Making Author(s): Chong-do Hah and Robert M. Lindquist Source: Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Dec., 1975), pp. 587-605 Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. on behalf of the Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2392025 Accessed: 26-02-2015 21:54 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Sage Publications, Inc. and Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Administrative Science Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.83.205.78 on Thu, 26 Feb 2015 21:54:11 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The 1952 Steel Seizure There is a paucity of conceptual approaches to and sys- Revisited: A Systematic tematic case studies of presidential decision making, especially in the area of domestic policy. The three mod- Study in Presidential els advanced by Graham T. Allison in Essence of Decision Decision Making are applied to the 1952 steel seizure to explain why Presi- dent Truman decided to seize the mills. -

A Program for Militant Trade Unionism

WHERE IS THE CIO GOING? By GEORGE MORRIS What happened to the c.I.O.? The question is heard on all sides. For some time it has been evident that the c.I.O. was being led away from the fighting, drive-ahead spirit that won it great sup port in earlier days. The sweeping organizing drives and pace setting economic gains that made it so attractive to the workers in the past are now giving way to internal strife, inter-union raid ing, Red-baiting, witch-hunting, stagnation and decline. The c.I.O.'s leaders were once the targets of union-haters. They were Red-baited. Today the union-haters sing hosannas to most of these very leaders beCause they themselves picked up Red-baiting and witch-hunting as weapons against progressives in the unions. The recent C.1.O. convention in Portland brought the long de veloping situation to a head. Differences carne out into the open and were fought out between the dominant Right and progressive Left. For the first time a c.I.O. convention faced two sets of resolutions. What's behind this · division in the C.1.O.? Who is responsible for it? How can the c.I.O. be brought back to the forward-looking path it followed in its earlier days? For an adequate answer to those questions we should first retrace the c.I.O.'s development both to the time of its birth-days when it was united and progressive -and further back, to the historic conditions that led to its rise. -

Amalgamated, PAC Back

Amalgamated, PAC 5 ——- ——— Back FDR > U. S. Needs Clothing 'Workers The Leadership, . ■' j CIO PAC Warns tit'll. Parley in Unanimous May NEWS, CHICAGO, 20—President Franklin I). Roosevelt is the na- Vote For 4th Term tional leader best fitted to guide CHICAGO, May 20—FDR in definitely the choice of the May this nation to a victorious peace, Amalgamated Clothing Workers. From start to finish of the the CIO Political Action Com- j union’s week-long convention, the 971 delegates, representing 22, mittee said this week in calling a peak membership of 325.000, refused to leave anyone in doubt unanimously for his re-nomina- for a moment. tion, and re-election as Com- , Nearly every mention of the President’s name—and there mander-in-Chief. were plenty—was greeted with an ■ 1944 ovation. The climax was a cheerful, In a meeting participated In by again into competing groups— wo snake-dancing demonstration when CIO Pres. Philip Murray, Chairman must have no dollar imperialism." the convention unanimously called Sidney Hillman of the PAC said Murray praised upon “the American people to make Hillman’s lead- that at a later meeting Vice-Pres. ership of ClO's political manifest their common will to draft activities. Henry A. Wallace probably would He compared Franklin D. Roosevelt for another the attacks on the also be endorsed for CPAC way re-nomination term in office.” with the the CIO it- and re-election, since nearly all CIO self was “castigated in the press." The resolution was adopted im- ; unions have endorsed him as well ClO’s political as FDR. -

Social Security Advisory Councils

+ocial Security Advisory Councils* by JAMES E. MARQUIS* A THIRTEEN-MEMBER advisory council, of the Eaton Manufacturing Company, Cleveland, Ohio. representing employers, employees, self-employed Leonard Woodcock, vice president of the United Auto- persons, and the public, was convened on June 10, mobile, Aircraft and Agricultural Implement Workers 1963, to begin a comprehensive review of the of America, Detroit, Mich. Nation’s old-age, survivors, and disability sys- tem. This is the second in a series of councils The study being undertaken by the 1963 ,4d- provided for under the 1956 amendments to the visory Council points up the continuing impor- Social Security A&; in 1966 and every fifth year tance tllat is attached to examination of the old- thereafter an advisory council will be appointed age, survivors, and disability insurance program to study and report on the financing of the by independent citizen groups. In the relatively program. brief history of the program, advisory councils The law gives the current council a special have contributed immensely to the planning and mission in addition to its function of considering development of old-age, survivors, and disability the financing of the program: It is directed to insurance protection. There is a long tradition study coverage, adequacy of benefits, and all dating back to 1934, before the passage of the other aspects of the program. A4 report of its Social Security Act, of seeking from representa- findings and recommendations must be submitted tive groups advice and guidance on the social to the Board of Trustees of the old-age and sur- securit,y program. -

Roosevelt and the Protest of the 1930S Seymour Martin Lipset

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1984 Roosevelt and the Protest of the 1930s Seymour Martin Lipset Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lipset, Seymour Martin, "Roosevelt and the Protest of the 1930s" (1984). Minnesota Law Review. 2317. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/2317 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Roosevelt and the Protest of the 1930s* Seymour Martin Lipset** INTRODUCTION The Great Depression sparked mass discontent and polit- ical crisis throughout the Western world. The economic break- down was most severe in the United States and Germany, yet the political outcome differed markedly in the two countries. In Germany the government collapsed, ushering the Nazis into power. In the United States, on the other hand, no sustained upheaval occurred and political change resulting from the eco- nomic crisis was apparently limited to the Democrats replacing the Republicans as the dominant party.' Why was the United States government able to survive intact the worst depression in modern times? Much of the answer lies in the social forces that have his- torically inhibited class conscious politics in the United States. Factors such as the unique character of the American class structure (the result of the absence of feudal hierarchical so- cial relations in its past), the great wealth of the country, the * This Article is part of a larger work dealing with the reasons why the United States is the only industrialized democratic country without a significant socialist or labor party. -

Community Activism

Community Activism "Unions were created to make living conditions just a little better than they were before they were created, and the union that does not manifest that kind of interest in human beings cannot endure." Philip Murray (1886-1952) First President of United Steelworkers of America 1942-1952 Our Union and its members are committed to working to improve the economic conditions in the communities where we live and work. We strive to build bridges within the labor movement and with community allies to build power for workers. AFL-CIO Constituency Organizations The AFL-CIO constituency organizations promote the full participation of women and minorities in the labor movement. Local union members and civil and human rights committee members are encouraged to affiliate and become involved with these organizations and other allies that further workers’ rights in our communities. See Appendix B. These organizations have local chapters. Civil and Human Rights Committees and the Community Services Initiative The Union’s Civil and Human Rights Community Service Initiative helps members with problems, works to make the community more responsive to the needs of workers, and builds union strength by reaching out to others committed to helping people and making our communities stronger. At the International Civil and Human Rights Conference in 2009, International Vice President for Human Affairs Fred Redmond charged all civil rights and human rights committees with the task of working to empower and mobilize our members. Community activism enhances the USW’s image in the community and creates strategic relationships in our communities that can help improve the overall condition of working people and those in need.