A Program for Militant Trade Unionism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democrats Play Into Hands of Mccarthy on Army Probe

Eisenhower Lies Build a Labor Party Note! About No Need THE MILITANT To Fear H-Bomb PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE By Art Preis Vol. X V III - No. 15 >267 NEW YORK. N. Y.. MONDAY. APRIL, 12, 1954 PRICE: 10 CENTS In a special A pril 5 broadcast intended to allay the mounting terror here and abroad over disclosure of the world-destroying power of the H-bomb, Eisenhower lied: “ I assure you we don’t have to fear . we don’t have to be tually to conceal the really awe hysterical.” some scope of destructiveness of If there is no reason to fear, a single H-bomb of the March why did they try to hide the 1 type. For it can do a lot more blood-chilling: facts about the H- than take out “any city.” Even the 1952 “baby” device was re Democrats Play Into Hands bomb exploded on March 1? Why did the Atomic Energy Commis vealed to have a mushroom sion keep silent until now about spread of a hundred miles. Every the results of the first hydro thing under that umbrella would gen blast in Nov. 1952? be subject to a deadly shower of Only after the horrifying facts radiation, not to speak of broil had leaked out piecemeal — fol in g heat. lowing the outcry in Japan about “The 1952 blast was exploded Of McCarthy on Army Probe the bu rn in g o f 23 fisherm en 80 at ground level,” observes the miles from the center of the April 1 Scripps-Howard report, March 1 detonation — did the “which probably would not be White House and AEC finally the method used in a wartime McCarthy Agrees to Probe, Provided .. -

November 2020 Heshvan - Kislev 5781 1 EVAN ZUCKERMAN President

A monthly publication of the Pine Brook Jewish Center. Serving the needs of our diverse Jewish community for more than 120 years. CANDLESTICK Clergy and Staff Mark David Finkel, Rabbi Menachem Toren, Cantor Dr. Asher Krief, Rabbi Emeritus Michelle Zuckerman, Executive Director Arlene Lopez, Office Administrator Karen Herbst, Office Administrator Mary Sheydwasser, Educational Director Lisa Lerman and Jill Buckler, Nursery School Co-Directors Robin Mangino, Religious School Administrator Esterina Herman, Bookkeeper Synagogue Officers Evan Zuckerman, President Michael Weinstein, 1st Vice President Jonathan Lewis, 2nd Vice President Betsy Steckelman, 3rd Vice President Seth Friedman, Treasurer Barry Marks, Financial Secretary Mike Singer, Corresponding Secretary Jay Thailer, Men’s Club President Fran Simmons and Ilene Thailer, Sisterhood Co-Presidents Religious Service Times Friday Evenings at 8:00 p.m. The family service is held on the first Friday of each month at 7:00 p.m. instead of 8:00 p.m. from September though June. Saturday Mornings at 9:45 a.m. with preliminary prayers at 9:30 a.m. Emergency Contact Information Please use the following protocol in the event of an emergency or if you lose a loved one: Call the synagogue office at 973-244-9800. If the office is closed, call Rabbi Finkel at (973) 287-7047 (home) or (973) 407-0065 (cell). If you are unable to reach the Rabbi, contact Cantor Toren at (973) 980-7777 or Michelle Zuckerman at (973) 886-5456. RABBI’S MESSAGE RABBI MARK DAVID FINKEL Havdalah by the Light of the Moon Some years ago when I was returning home after my graduate year of study at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, I took the opportunity to take a stop in Scandinavia (travel was simpler at that time). -

Change World!

DAILY WORKER, NEFt IORK, TUESDAY, JANUARY 23, 1934 Page Five Artists in Boston Magazine of N. Y. Organize to Probe TO COMRADE John Reed Club to Do Workers Want Culture? CHANGE lj* Waft. LENIN CWA Art Project ========= By ISIDOR SCHNEIDER ========== Appear Jan. 29th Yes, Say Theatre Union Spokesmen. Citing . Own =THE= BOSTON, Jan, 22.—Boston artists.; “The Tartar eyes . i The John Reed Club of New York " . members of a committee elected at a 1 cold ... inscrutable .. Asian mystery . announces the publication of Parti- Experience With 'Worker-Audience** san Review, a bi-monthly magazine mass meeting of artists Thursday - By PAUL PETERS ■. night, today notified Francis Henry The paid pens pour out their blots lof revolutionary literature and criti- cism, to appear on Jan. 29th. The WORLD! to hide you from us. JAN. 11 the Theatre Union pre- press. That was the first step. A Taylor, New England Regional Chair- I will The janitors of History magazine contain fiction, poetry, sented “Peace cn Earth,” of rtio man for the Public Works of Art Marxist criticism and reviews expres- ON the corps volunteer speakers By Michael Gold through i Project, that they would call upon work to drag you their halls ...of Fame anti-war play by George Skiar and were imbued with the idea of the sing the revolutionary direction of was the his committee next Tuesday at the wreathed with cartridge clips, haloed in gun blasts.— the American workers and intellectu- Albert Maltz, for the fiftieth time. theatre nevt step. They spoke at two or throe meetings a Is Ben Gold a Poet? Yes! Gardner Museum. -

Youngstown State University Oral History Program

YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM 1952 Youngstown Sheet & Tube Steel Strike Personal Experience O.H. 1218 RUSSELL L. THOMAS Interviewed by Andrew Russ on October 28, 1988 Russell Thomas resides in North Jackson, Ohio and was born on January 18, 1908 in East Palestine, Ohio. He attended high school in Coitsville, Ohio and eventually was employed for the United Steel Workers of America in the capacity of local union representative. Tn this capacity, he worked closely with the Youngstown's local steel workers' unions. It was from this position that he experienced the steel strike of 1952. Mr. Thomas, after relating his biography, went on to discuss the organization of the Youngstown contingent of the United Steel Workers of America. He went into depth into the union's genera- tion, it's struggle with management, and the rights it obtained for the average worker employed in the various steel mills of Youngstown. He recollected that the steel strike of 1952 was one that was different in the respect that President Truman had taken over the operation of the mills in order to prosecute the Korean War effort. He also discussed local labor politics as he had run for the posiUon of local union president. Although he was unsuccessful in this bid for office, his account of just how the local labor political game was played provided great insight into the labor movement's influence upon economic issues and public opinion. His interview was different in that it discussed not only particular issues that affected the average Youngstown worker employed in steel, but also broad political and economic ones that molded this period of American labor history. -

Experiences of C.W. Editor in Steel Towns with C.I.O

Experiences of C.W. Editor in Steel Towns with C.I.O. Dorothy Day The Catholic Worker, August 1936, 1, 2. *Summary: Impressions from a fact-finding tour of Pennsylvania steel towns and interviews with such figures as Bishop Boyle of Pittsburgh; John L. Lewis, chairman of the CIO; Kathryn Lewis, his daughter; and John Brophy, Director of the CIO. For readers seeking background information on the steel/labor struggle, she recommends several books. Applauds church and government efforts to support labor in its struggle to organize and notes with satisfaction The CW ’s ability to transcend race and ethnic boundaries. Keywords: labor, unions, social teaching (DDLW #302).* A story like this is too big to compress in one column. Impressions crowded upon one over two weeks of constant observation are hard to put down on paper. There could be an interview with Bishop Boyle of Pittsburgh; with John L. Lewis, chairman of the Committee on Industrial Organization; with John Brophy, director of the committee; with Philip Murray, head of the Steel Workers’ Organization Committee (SWOC); with Pat Fagin, president of District No. 5 of the United Mine Workers; with the wives and mothers of steel workers; with Father Kazincy, who spoke from a wooden platform out in an open air mass meeting at Braddock last Sunday; with Smiley Chatak, the young organizer of the Allegheny Valley; with the Slovaks, the Croatians, the Syrians, the Italians and the Americans I have been seeing this past month–individuals among the 500,000 steel workers who have been unorganized, oppressed and enslaved for the last half century in the giant mills of the American Iron and Steel Institute. -

The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 Bargaining for Security: The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960 Henry Edward Himes III [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Labor History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Himes, Henry Edward III, "Bargaining for Security: The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3917. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3917 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bargaining for Security: The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960 Henry E. Himes III Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Ken Fones-Wolf, PhD., Chair Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, PhD. -

"A Road to Peace and Freedom": the International Workers Order and The

“ A ROAD TO PEACE AND FREEDOM ” Robert M. Zecker “ A ROAD TO PEACE AND FREEDOM ” The International Workers Order and the Struggle for Economic Justice and Civil Rights, 1930–1954 TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia • Rome • Tokyo TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 www.temple.edu/tempress Copyright © 2018 by Temple University—Of The Commonwealth System of Higher Education All rights reserved Published 2018 All reasonable attempts were made to locate the copyright holders for the materials published in this book. If you believe you may be one of them, please contact Temple University Press, and the publisher will include appropriate acknowledgment in subsequent editions of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Zecker, Robert, 1962- author. Title: A road to peace and freedom : the International Workers Order and the struggle for economic justice and civil rights, 1930-1954 / Robert M. Zecker. Description: Philadelphia : Temple University Press, 2018. | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017035619| ISBN 9781439915158 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781439915165 (paper : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: International Workers Order. | International labor activities—History—20th century. | Labor unions—United States—History—20th century. | Working class—Societies, etc.—History—20th century. | Working class—United States—Societies, etc.—History—20th century. | Labor movement—United States—History—20th century. | Civil rights and socialism—United States—History—20th century. Classification: LCC HD6475.A2 -

Women in American Labor History: Course Module, Trade Union Women's Studies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 134 488 SO 009 696 AUTHOR Kopelov, Connie TITLE Women in American Labor History: Course Module, Trade Union Women's Studies. INSTITUTION State Univ. of New York, Ithaca. School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell Univ. PUB DATE Mar 76 VOTE 39p. AVAILABLE FROMNew York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Cornell University, 7 East 43rdStreet, New York, N.vis York 10017 ($2.00 paper cover) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$2.06 Plus Postage.' DESCRIPTORS Course Content; Economic Factors; Employees; Higher Education; i3i5tory Instruction; Labor Conditions; Labor Force; *Labor Unions; *Learning Modules; Political Influences; Social History; Socioeconomic Influences; *United States History; *Womers Studies; *Working Women ABSTRACT The role of working women in American laborhistory from colonial times to the present is the topicof this learning module. Intended predominantlyas a course outline, the module can also be used to supplement courses in social,labor, or American history. Information is presentedon economic and political influences, employment of women, immigration,vomen's efforts at labor organization, percentage of female workersat different periods, women in labor strikes, feminism,sex discrimination, maternity disabilitye and equality in the workplace. The chronological narrative focuses onwomen in the United States during the colonial period, the Revolutionary War period,the period from nationhood to the Civil War, from the CivilWar to 1900, from 1900 to World War I, from World War I to World War II,from World War II to 1960, and from 1960 through 1975. Each section isintroduced by a paragraph or short essay that highlights the majorevents of the period, followed by a series of topics whichare discussed and described by quotations, historical information,case studies, and accounts of relevant laws. -

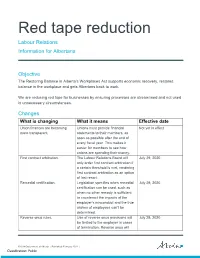

Red Tape Reduction: Labour Relations Information for Albertans-2021

Red tape reduction Labour Relations Information for Albertans Objective The Restoring Balance in Alberta’s Workplaces Act supports economic recovery, restores balance in the workplace and gets Albertans back to work. We are reducing red tape for businesses by ensuring processes are streamlined and not used in unnecessary circumstances. Changes What is changing What it means Effective date Union finances are becoming Unions must provide financial Not yet in effect more transparent. statements to their members, as soon as possible after the end of every fiscal year. This makes it easier for members to see how unions are spending their money. First contract arbitration. The Labour Relations Board will July 29, 2020 only order first contract arbitration if a certain threshold is met, rendering first contract arbitration as an option of last resort. Remedial certification. Legislation specifies when remedial July 29, 2020 certification can be used, such as when no other remedy is sufficient to counteract the impacts of the employer’s misconduct and the true wishes of employees can’t be determined. Reverse onus rules. Use of reverse onus provisions will July 29, 2020 be limited to the employer in cases of termination. Reverse onus will ©2018 Government of Alberta | Published: February 2021 | Classification: Public also apply to unions in cases where they have used coercion or intimidation in organizing campaigns. Early renewal of collective This will cut red tape for employers February 10, 2021 agreements. and unions by allowing early renewal of existing agreements, so long as employees consent. Consequences for prohibited Unions can be refused certification if July 29, 2020 practices conducted by union. -

Soviet Union

REPORT of the CIO DELEGATION to the SOVIET UNION Submitted by JAMES B. CAREY Secretary-Treasurer, CIO Chairman of the Delegation Other Members of the Delegation: JOSEPH CURRAN REID ROBINSON rice-President, CIO Fice-P resident , CIO President, N at ional M arit ime Union President , Lnt crnational Union of .lIint', J / ill and Smelt er Il'orkers ALBERTJ . FITZGERALD r ice-Pre siden t, CIO LEE PRESSMAN President , Un ited E lect rical, R adio and General Couusrl, c/o JIacliine W orkers 0/ .Inisr ica JOHN GREEN JOHN ABT rice-President, CIO General Cou nsel, Amalgamat ed Clot hing President, Indust rial Union 0/ M an ne and W orku 5 0/ .lmeri ca Sh ipb uilding W orlecrs LEN DE CAUX ALLAN S. HAYWOOD Pu blicit y D irect or, CIO, and E dit or, Tilt' Fice -President, CIO C/O N m 's D irector 0/ Organization, CIO EMIL RIEVE VINCENT SWEENEY r ia-President, CIO Pu blicit y D irect or, United St rrlzcorlerrs President, T ext ile W orkers Union oi A merica 0/ A merica; Editor, St eel Labor Publication No. 128 Price 15c per copy; 100 for $10.00; 500 for $40.00 D epartment of International Affairs Order Literature from Publicity Department CONGRESS OF INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATIONS 718 JACKSON PLACE, N. W. WASHINGTON 6, D. C. \ -- . ~ 2 rr To Promote Friendship And Understanding... " H E victo ry of the United Nations over the military power of fascism T opened up prospects of a new era of int ern ational understanding, democratic progress, world peace and prosperity. -

The Jews and the Post-War Reaction After 1918

STORIES OF THREE HUNDRED YEARS: XIV THE JEWS AND THE POST-WAR REACTION AFTER 1918 By Morris U. Schappes AFTER World War I the economic rulers of our coun pos1uons in Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Indiana, Ohiq, try were bloated but of course not satiated. The United California and Oregon. This racism on a rampage of States had in 1914 been a debtor nation, owing money to course spilled over into the mounting hostility to the immi foreign investors, but in 1918 i~ was a creditor to a good grant masses that was being whipped up at the same time. part of the capitalist world. War profiteering, as subse Racist theories of Anglo-Saxon superiority now fused with quent official investigations revealed, had been rampant the new look anti-Bolshevik hysteria and the chairman of and even the ordinary profits were enormous. Real wage$ the Senate Committee on Immigration, Senator Thomas however, declined and in many ways, remarks one economic R. Hardwick, "proposed restricting immigration as a means historian, "the immediate effect of the war appeared det of keeping out Bolshevism.us rimental to labor."! One immediate result that had far-reaching effects upon Swollen though these ruling circles were with newly the Jewish people here and abroad was the immigration gorged wealth and power, they were haunted by a new law of 1920. The preamble to the law baldly accepted form of the ancient fear of the organized workers and the false premise of Anglo-Saxon supremacy, while the law the people aroused, which they suddenly saw triumphantly itself aimed to encourage Anglo-Saxon immigration from embodied in the new Russian revolutionary government. -

The Little Steel Strike of 1937

This dissertation has been Mic 61-2851 microfilmed exactly as received SOFCHALK, Donald Gene. THE LITTLE STEEL STRIKE OF 1937. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1961 History, modem ; n University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE LITTLE STEEL STRIKE OF 1937 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Donald Gene Sofchalk, B. A., M. A. ***** The Ohio State University 1961 Approved by Adviser Department of History PREFACE On Sunday, May 30, 1937, a crowd of strikers and sympathizers marched toward the South Chicago plant of the Republic Steel Corpora tion. The strikers came abreast a line of two hundred Chicago police, a scuffle ensued, and the police opened fire with tear gas and revolvers. Within minutes, ten people were dead or critically injured and scores wounded. This sanguinary incident, which came to be known as the "Memorial Day Massacre," grew out of a strike called by the Steel Workers Or&soizing Committee of the CIO against the so-called Little Steel companies. Two months previously the U. S. Steel Corporation, traditional "citadel of the open shop," had come to terms with SWOC, but several independent steel firms had refused to recognize the new union. Nego tiations, never really under way, had broken down, and SWOC had issued a strike call affecting about eighty thousand workers in the plants of Republic, Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company, and Inland Steel Company in six states. The Memorial Day clash, occurring only a few days after the * strike began, epitomized and undoubtedly intensified the atmosphere of mutual hostility which characterized the strike.