Comedy and Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TPTV Schedule Dec 10Th - 16Th 2018

TPTV Schedule Dec 10th - 16th 2018 DATE TIME PROGRAMME SYNOPSIS Mon 10 6:00 The Case of 1949. Drama. Made at Merton Park Studios, based on a true story, Dec 18 Charles Peace directed by Norman Lee. The film recounts the exploits through the trial of Charles Peace. Starring Michael Martin-Harvey. Mon 10 7:45 Stagecoach West A Place of Still Waters. Western with Wayne Rogers & Robert Bray, who Dec 18 run a stagecoach line in the Old West where they come across a wide variety of killers, robbers and ladies in distress. Mon 10 8:45 Glad Tidings 1953. Drama. Colonel's adult children object to him marrying an Dec 18 American widow. Starring Barbara Kelly and Raymond Huntley. Mon 10 10:05 Sleeping Car To 1948. Drama. Director: John Paddy Carstairs. Stars Jean Kent, Bonar Dec 18 Trieste Colleano, Albert Lieven & David Tomlinson. Agents break into an embassy in Paris to steal a diary filled with political secrets. Mon 10 11:55 Hell in the Pacific 1968. Adventure. Directed by John Boorman and starring Lee Marvin Dec 18 and Toshiro Mifune. During World War II, an American pilot and a Japanese navy captain are deserted on an island in the Pacific Ocean Mon 10 14:00 A Family At War 1971. Clash By Night. Created by John Finch. Stars John McKelvey & Dec 18 Keith Drinkel. A still-blind Phillip encounters an old enemy who once shot one of his comrades in the Spanish Civil War. (S2, E16) Mon 10 15:00 Windom's Way 1957. Drama. Directed by Ronald Neame. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

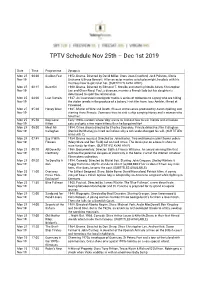

TPTV Schedule Nov 25Th – Dec 1St 2019

TPTV Schedule Nov 25th – Dec 1st 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 25 00:00 Sudden Fear 1952. Drama. Directed by David Miller. Stars Joan Crawford, Jack Palance, Gloria Nov 19 Grahame & Bruce Bennett. After an actor marries a rich playwright, he plots with his mistress how to get rid of her. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 02:15 Beat Girl 1960. Drama. Directed by Edmond T. Greville and starring Noelle Adam, Christopher Nov 19 Lee and Oliver Reed. Paul, a divorcee, marries a French lady but his daughter is determined to spoil the relationship. Mon 25 04:00 Last Curtain 1937. An insurance investigator tracks a series of robberies to a gang who are hiding Nov 19 the stolen jewels in the produce of a bakery. First film from Joss Ambler, filmed at Pinewood. Mon 25 05:20 Honey West 1965. Matter of Wife and Death. Classic crime series produced by Aaron Spelling and Nov 19 starring Anne Francis. Someone tries to sink a ship carrying Honey and a woman who hired her. Mon 25 05:50 Dog Gone Early 1940s cartoon where 'dog' wants to find out how to win friends and influence Nov 19 Kitten cats and gets a few more kittens than he bargained for! Mon 25 06:00 Meet Mr 1954. Crime drama directed by Charles Saunders. Private detective Slim Callaghan Nov 19 Callaghan (Derrick De Marney) is hired to find out why a rich uncle changed his will. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 07:45 Say It With 1934. Drama musical. Directed by John Baxter. Two well-loved market flower sellers Nov 19 Flowers (Mary Clare and Ben Field) fall on hard times. -

The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 22 | 2021 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.36228 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Marie Ventura, “Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx”, Miranda [Online], 22 | 2021, Online since 02 March 2021, connection on 27 April 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.36228 This text was automatically generated on 27 April 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx 1 Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Introduction: a Transnational Trickster 1 In early autumn, 1933, New York critic Alexander Woollcott telephoned his friend Harpo Marx with a singular proposal. Having just learned that President Franklin Roosevelt was about to carry out his campaign promise to have the United States recognize the Soviet Union, Woollcott—a great friend and supporter of the Roosevelts, and Eleanor Roosevelt in particular—had decided “that Harpo Marx should be the first American artist to perform in Moscow after the US and the USSR become friendly nations” (Marx and Barber 297). “They’ll adore you,” Woollcott told him. “With a name like yours, how can you miss? Can’t you see the three-sheets? ‘Presenting Marx—In person’!” (Marx and Barber 297) 2 Harpo’s response, quite naturally, was a rather vehement: you’re crazy! The forty-four- year-old performer had no intention of going to Russia.1 In 1933, he was working in Hollywood as one of a family comedy team of four Marx Brothers: Chico, Harpo, Groucho, and Zeppo. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1930S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1930s Page 42 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1930 A Little of What You Fancy Don’t Be Cruel Here Comes Emily Brown / (Does You Good) to a Vegetabuel Cheer Up and Smile Marie Lloyd Lesley Sarony Jack Payne A Mother’s Lament Don’t Dilly Dally on Here we are again!? Various the Way (My Old Man) Fred Wheeler Marie Lloyd After Your Kiss / I’d Like Hey Diddle Diddle to Find the Guy That Don’t Have Any More, Harry Champion Wrote the Stein Song Missus Moore I am Yours Jack Payne Lily Morris Bert Lown Orchestra Alexander’s Ragtime Band Down at the Old I Lift Up My Finger Irving Berlin Bull and Bush Lesley Sarony Florrie Ford Amy / Oh! What a Silly I’m In The Market For You Place to Kiss a Girl Everybody knows me Van Phillips Jack Hylton in my old brown hat Harry Champion I’m Learning a Lot From Another Little Drink You / Singing a Song George Robey Exactly Like You / to the Stars Blue Is the Night Any Old Iron Roy Fox Jack Payne Harry Champion I’m Twenty-one today Fancy You Falling for Me / Jack Pleasants Beside the Seaside, Body and Soul Beside the Sea Jack Hylton I’m William the Conqueror Mark Sheridan Harry Champion Forty-Seven Ginger- Beware of Love / Headed Sailors If You were the Only Give Me Back My Heart Lesley Sarony Girl in the World Jack Payne George Robey Georgia On My Mind Body & Soul Hoagy Carmichael It’s a Long Way Paul Whiteman to Tipperary Get Happy Florrie Ford Boiled Beef and Carrots Nat Shilkret Harry Champion Jack o’ Lanterns / Great Day / Without a Song Wind in the Willows Broadway Baby Dolls -

MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian

#10 silent comedy, slapstick, music hall. CONTENTS 3 DVD news 4Lost STAN LAUREL footage resurfaces 5 Comedy classes with Britain’s greatest screen co- median, WILL HAY 15 Sennett’s comedienne MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian 19 Did STAN LAUREL & LUPINO LANE almost form a team? 20 Revelations and rarities : LAUREL & HARDY, RAYMOND GRIFFITH, WALTER FORDE & more make appearances at Kennington Bioscope’s SILENT LAUGHTER SATURDAY 25The final part of our examination of CHARLEY CHASE’s career with a look at his films from 1934-40 31 SCREENING NOTES/DVD reviews: Exploring British Comedies of the 1930s . MORE ‘ACCIDENTALLY CRITERION PRESERVED’ GEMS COLLECTION MAKES UK DEBUT Ben Model’s Undercrank productions continues to be a wonderful source of rare silent comedies. Ben has two new DVDs, one out now and another due WITH HAROLD for Autumn release. ‘FOUND AT MOSTLY LOST’, presents a selection of pre- LLOYD viously lost films identified at the ‘Mostly Lost’ event at the Library of Con- gress. Amongst the most interesting are Snub Pollard’s ‘15 MINUTES’ , The celebrated Criterion Collec- George Ovey in ‘JERRY’S PERFECT DAY’, Jimmie Adams in ‘GRIEF’, Monty tion BluRays have begun being Banks in ‘IN AND OUT’ and Hank Mann in ‘THE NICKEL SNATCHER’/ ‘FOUND released in the UK, starting AT MOSTLY LOST is available now; more information is at with Harold Lloyd’s ‘SPEEDY’. www.undercrankproductions.com Extra features include a com- mentary, plus documentaries The 4th volume of the ‘ACCIDENTALLY PRESERVED’ series, showcasing on Lloyd’s making of the film ‘orphaned’ films, many of which only survive in a single print, is due soon. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Theatre Archive Project

THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT http://sounds.bl.uk Auston Cole – interview transcript Interviewer: Dominic Shellard 6 November 2007 Theatre-goer. Frank Adie; Tommy Cooper; Cecily Courtneidge; Noel Coward; G.H. Elliot; Roy Hudd; Jack and Claude Hulbert; London Coliseum; Murray and Mooney; music hall; new writing; Ivor Novello; Beryl Reid; Sheffield theatres; theatre seating; variety; Waiting for Godot; West End. DS: Well, welcome to the British Library Austin, and thank you very much indeed for agreeing to be interviewed for the AHRC British Library Theatre Archive Project. AC: Thank you. DS: Could I just ask you first of all whether you’re happy for the interview to deposited in the British Library Sound Archive. AC: I’m totally happy with that. DS: Thank you very much indeed. And perhaps we can start by discussing how you first became interested in the theatre. AC: That’s quite simple Dominic, and I’m glad you asked me that as a kick-off, because before the war my parents took me to London, to the theatre. And also we had two theatres in Cambridge. I was born in a village not far from Cambridge, and that was our weekend visiting town – now it’s a city. And I realised that anywhere I went, if I could get in theatre – that’s what as I thought of as I worked so hard, no matter all stages of my life – I found that when I’d finished that, the thought was ‘where can I get into the theatre?’. DS: Wonderful. AC: Now, as a consequence of that, little wonder then when the war came and I was recruited into a particular service of the Royal Navy. -

Jack Oakie & Victoria Horne-Oakie Films

JACK OAKIE & VICTORIA HORNE-OAKIE FILMS AVAILABLE FOR RESEARCH VIEWING To arrange onsite research viewing access, please visit the Archive Research & Study Center (ARSC) in Powell Library (room 46) or e-mail us at [email protected]. Jack Oakie Films Close Harmony (1929). Directors, John Cromwell, A. Edward Sutherland. Writers, Percy Heath, John V. A. Weaver, Elsie Janis, Gene Markey. Cast, Charles "Buddy" Rogers, Nancy Carroll, Harry Green, Jack Oakie. Marjorie, a song-and-dance girl in the stage show of a palatial movie theater, becomes interested in Al West, a warehouse clerk who has put together an unusual jazz band, and uses her influence to get him a place on one of the programs. Study Copy: DVD3375 M The Wild Party (1929). Director, Dorothy Arzner. Writers, Samuel Hopkins Adams, E. Lloyd Sheldon. Cast, Clara Bow, Fredric March, Marceline Day, Jack Oakie. Wild girls at a college pay more attention to parties than their classes. But when one party girl, Stella Ames, goes too far at a local bar and gets in trouble, her professor has to rescue her. Study Copy: VA11193 M Street Girl (1929). Director, Wesley Ruggles. Writer, Jane Murfin. Cast, Betty Compson, John Harron, Ned Sparks, Jack Oakie. A homeless and destitute violinist joins a combo to bring it success, but has problems with her love life. Study Copy: VA8220 M Let’s Go Native (1930). Director, Leo McCarey. Writers, George Marion Jr., Percy Heath. Cast, Jack Oakie, Jeanette MacDonald, Richard “Skeets” Gallagher. In this comical island musical, assorted passengers (most from a performing troupe bound for Buenos Aires) from a sunken cruise ship end up marooned on an island inhabited by a hoofer and his dancing natives. -

Fred Tomlin (Boom Operator) 1908 - ? by Admin — Last Modified Jul 27, 2008 02:45 PM

Fred Tomlin (boom operator) 1908 - ? by admin — last modified Jul 27, 2008 02:45 PM BIOGRAPHY: Fred Tomlin was born in 1908 in Hoxton, London, just around the corner from what became the Gainsborough Film Studios (Islington) in Poole Street. He first visited the studio as a child during the filming of Woman to Woman (1923). He entered the film industry as an electrician, working in a variety of studios including Wembley, Cricklewood and Islington. At Shepherd’s Bush studio he got his first experience as a boom operator, on I Was A Spy (1933). Tomlin claims that from that point until his retirement he was never out of work, but also that he was never under permanent contract to any studio, working instead on a freelance basis. During the 1930s he worked largely for Gaumont and Gainsborough on films such as The Constant Nymph (1933), Jew Suss (1934), My Old Dutch (1934), and on the Will Hay comedies, including Oh, Mr Porter (1937) and Windbag the Sailor (1936). During the war, Tomlin served in the army, and on his return continued to work as a boom operator on films and television (often alongside Leslie Hammond) until the mid 1970s. His credits include several films for Joseph Losey (on Boom (1968) and Secret Ceremony (1968)) and The Sea Gull (1968)for Sidney Lumet, as well as TV series such as Robin Hood and The Buccaneers and a documentary made in Cuba for Granada TV. SUMMARY: In this interview from 1990, Tomlin talks to Bob Allen about his career, concentrating mainly on the pre-war period. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Ask a Policeman Free

FREE ASK A POLICEMAN PDF The Detection Club,Agatha Christie,Dorothy L. Sayers,Anthony Berkeley,Gladys Mitchell,Helen Simpson | 336 pages | 08 Nov 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007468621 | English | London, United Kingdom Ask a Policeman () directed by Marcel Varnel • Reviews, film + cast • Letterboxd The mirthful adventures of Police-Sergeant Samuel Dudfoot and his Ask a Policeman constables, Albert Brown and Jeremias Harbottle, who stage a fabricated crime-wave to save their jobsand then find themselves involved in the real thing. Derick Williams Jack Parry. Will Hay and his incompetent gang as village coppers! No other outcome then a comedy classic is possible! And might perhaps be Hay's Ask a Policeman too? The village of Turnbotham Round has the reputation of being the safest place in England with not a single crime committed in 10 years 4 months and 5 days. Which just happens to be the exact same amount of time that Sergeant Samuel Dudfoot Will Hay has been in charge of the local police station. Unfortunately when that information comes to the attention of the Chief Constable he threatens to close the station down and put Dudfoot and his two constables out of work, so it now falls to them to come up with some crime. Luckily, and unsurprisingly, the very thing they need has Ask a Policeman going on under their noses for at least the last 10 years 4 months…. This is a hugely enjoyable yarn about three incompetent and Ask a Policeman bent coppers who somehow manage to thwart a major smuggling operation. This is a lot of fun, I've liked Will Hay comedies since I first saw them as a boy, and this one Ask a Policeman solid, with snappy, amusing dialogue from the shady, but good-hearted, boys.