The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood

Katherine Kinney Cold Wars: Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood n 1982 Louis Gossett, Jr was awarded the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Gunnery Sergeant Foley in An Officer and a Gentleman, becoming theI first African American actor to win an Oscar since Sidney Poitier. In 1989, Denzel Washington became the second to win, again in a supporting role, for Glory. It is perhaps more than coincidental that both award winning roles were soldiers. At once assimilationist and militant, the black soldier apparently escapes the Hollywood history Donald Bogle has named, “Coons, Toms, Bucks, and Mammies” or the more recent litany of cops and criminals. From the liberal consensus of WWII, to the ideological ruptures of Vietnam, and the reconstruction of the image of the military in the Reagan-Bush era, the black soldier has assumed an increasingly prominent role, ironically maintaining Hollywood’s liberal credentials and its preeminence in producing a national mythos. This largely static evolution can be traced from landmark films of WWII and post-War liberal Hollywood: Bataan (1943) and Home of the Brave (1949), through the career of actor James Edwards in the 1950’s, and to the more politically contested Vietnam War films of the 1980’s. Since WWII, the black soldier has held a crucial, but little noted, position in the battles over Hollywood representations of African American men.1 The soldier’s role is conspicuous in the way it places African American men explicitly within a nationalist and a nationaliz- ing context: U.S. history and Hollywood’s narrative of assimilation, the combat film. -

Online Versions of the Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Urls September

Online versions of the Handouts have color images & hot urls September 6, 2016 (XXXIII:2) http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html Sam Wood, A NIGHT AT THE OPERA (1935, 96 min) DIRECTED BY Sam Wood and Edmund Goulding (uncredited) WRITING BY George S. Kaufman (screenplay), Morrie Ryskind (screenplay), James Kevin McGuinness (from a story by), Buster Keaton (uncredited), Al Boasberg (additional dialogue), Bert Kalmar (draft, uncredited), George Oppenheimer (uncredited), Robert Pirosh (draft, uncredited), Harry Ruby (draft uncredited), George Seaton (draft uncredited) and Carey Wilson (uncredited) PRODUCED BY Irving Thalberg MUSIC Herbert Stothart CINEMATOGRAPHY Merritt B. Gerstad FILM EDITING William LeVanway ART DIRECTION Cedric Gibbons STUNTS Chuck Hamilton WHISTLE DOUBLE Enrico Ricardi CAST Groucho Marx…Otis B. Driftwood Chico Marx…Fiorello Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Harpo Marx…Tomasso Races (1937) that his career picked up again. Looking at the Kitty Carlisle…Rosa finished product, it is hard to reconcile the statement from Allan Jones…Ricardo Groucho Marx who found the director "rigid and humorless". Walter Woolf King…Lassparri Wood was vociferously right-wing in his personal views and this Sig Ruman… Gottlieb would not have sat well with the famous comedian. Wood Margaret Dumont…Mrs. Claypool directed 11 actors in Oscar-nominated performances: Robert Edward Keane…Captain Donat, Greer Garson, Martha Scott, Ginger Rogers, Charles Robert Emmett O'Connor…Henderson Coburn, Gary Cooper, Teresa Wright, Katina Paxinou, Akim Tamiroff, Ingrid Bergman and Flora Robson. Donat, Paxinou and SAM WOOD (b. July 10, 1883 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—d. Rogers all won Oscars. Late in his life, he served as the President September 22, 1949, age 66, in Hollywood, Los Angeles, of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American California), after a two-year apprenticeship under Cecil B. -

The Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide the Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide

(Read free ebook) The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide QxKpnBVVk The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide GF-51433 USmix/Data/US-2015 4.5/5 From 294 Reviews Kevin C. Fitzpatrick DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub 13 of 13 people found the following review helpful. A great way to introduce yourself to a group who made literary historyBy Greg HatfieldIt seems my entire life has been connected to the Algonquin Round Table. When I first discovered Harpo Marx, as a youngster, it led me to his autobiography, Harpo Speaks,where I then learned about the Round Table. Alexander Woollcott, George S. Kaufman, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Franklin P. Adams, Edna Ferber, Heywood Broun, and all the rest who made up the Vicious Circle, became an obsession to me and I had to learn about their lives and, more importantly, their work.Kevin Fitzpatrick has done a remarkable job with this book, putting the group into a historical perspective, and giving the reader a terrific overview of what made the Algonquin Round Table unique and worthy of your time. They were the leading writers and critics of the 1920's, who really did enjoy one another's company, meeting practically every day for lunch for ten years at the Algonquin Hotel.Fitzpatrick says, in one section, that there isn't a day, in this modern era, where someone, somewhere, mentions one of the group in a glowing context (I'm paraphrasing here). The fact remains that the work of Kaufman, Mrs. -

Tm Array 1 Present Alcorn

v ; •&-Z: V. I--<f ,2 feilS ^^*;vV.'- s. 'v.", '.••< :, •-:• •;•;,&• ^rUO»V: ' S THE PRESS IS® A .A i*-.A /,{••'fo'jj-T An Institution Which Works wm-": THE PRESS A Home Town Paper For :0 For Community Ad- \ s!i vancement. r ; \ Home /Town •• . : -r I IS asie'. Folks. THE ONLY NEWSPAPER PUBLISHED IN THE TOWN OF ENFIELl), CONN. 't'H\}5% FORTY-SEVENTH YEAH—NO. 24. THOMPSONVILLE, CONNECTICUT, THURSDAY, OCTOBER 7, 1926 PRICE $2.00 A YEAR—SINGLE COPY 5c. .T.MARRAY 1 Frank A. Simmons TOWN SEEKS TO ^v*Civic Program DR. VAIL AGAIN First Selectmen TOWN MEETING fil New Tax Collector RECOVER AMOUNT i^v?Up To Nov. 2. HEADS THE TOWN James T. Murray MAKES NO CHANGE .. Saturday, Oct. 9, Wednesday, OF TAX SHORTAGE Oct. 13, and Saturday, Oct. 16: c •' 'v^ >-*' SCHOOL BOARD IN THE BUDGET Mill inn i i Meeting of the Selectmen and Defeats A. J. Epstein by Town Clerk to admit electors Formal Demand Made from the perfected list. Any Hertry R. Cooper is Also Finance Board Recom i Majority of 203 Votes— of the Surety Company prospective elector who is not made at this meeting cannot Reelected Secretary at mendations are Adopt Frank A. Simmons Is in Which Former Town vote at the state election, No Reorganization Meet I Successful in the Tax vember 2nd. I ed—Property Tax Col Was Bonded, To Make Monday, Oct. 11: Caucus of ing of the Board Held lector's Pay Made $1,- ? Collector Contest. • W Good the Defalcation. Republican electors in the Hig- gins School 'Auditorium, for the Tuesday Afternoon. -

Orson Welles: CHIMES at MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 Min

October 18, 2016 (XXXIII:8) Orson Welles: CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 min. Directed by Orson Welles Written by William Shakespeare (plays), Raphael Holinshed (book), Orson Welles (screenplay) Produced by Ángel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman Music Angelo Francesco Lavagnino Cinematography Edmond Richard Film Editing Elena Jaumandreu , Frederick Muller, Peter Parasheles Production Design Mariano Erdoiza Set Decoration José Antonio de la Guerra Costume Design Orson Welles Cast Orson Welles…Falstaff Jeanne Moreau…Doll Tearsheet Worlds" panicked thousands of listeners. His made his Margaret Rutherford…Mistress Quickly first film Citizen Kane (1941), which tops nearly all lists John Gielgud ... Henry IV of the world's greatest films, when he was only 25. Marina Vlady ... Kate Percy Despite his reputation as an actor and master filmmaker, Walter Chiari ... Mr. Silence he maintained his memberships in the International Michael Aldridge ...Pistol Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Tony Beckley ... Ned Poins and regularly practiced sleight-of-hand magic in case his Jeremy Rowe ... Prince John career came to an abrupt end. Welles occasionally Alan Webb ... Shallow performed at the annual conventions of each organization, Fernando Rey ... Worcester and was considered by fellow magicians to be extremely Keith Baxter...Prince Hal accomplished. Laurence Olivier had wanted to cast him as Norman Rodway ... Henry 'Hotspur' Percy Buckingham in Richard III (1955), his film of William José Nieto ... Northumberland Shakespeare's play "Richard III", but gave the role to Andrew Faulds ... Westmoreland Ralph Richardson, his oldest friend, because Richardson Patrick Bedford ... Bardolph (as Paddy Bedford) wanted it. In his autobiography, Olivier says he wishes he Beatrice Welles .. -

Coast Guard Combat Veterans Association

QuarterQuarterthe deckdeck LogLog Membership publication of the Coast Guard Combat Veterans Association. Publishes quarterly –– Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall. Not sold on a subscription basis. The Coast Guard Combat Veterans Association is a Non-Profit Corporation of Active Duty Members, Retired Members, Reserve Members, and Honorably Discharged Former Members of the United States Coast Guard who served in, or provided direct support to combat situations recognized by an appropriate military award while serving as a member of the United States Coast Guard. Volume 19, Number 4 Winter 2004 What Are They Doing Now? Reuniting With Previous CGCVA Coast Guard Persons of the Year At our 2002 Convention & Reunion in Reno, we voted to with the severely injured pilot, Kelly jumped into the frigid 20- make all those selected as CGCVACoast Guard Persons of the foot seas and swam to the survivor. In addition to his injuries Year Honorary Life Members of our Association (if they and hypothermia, the pilot was entangled in his parachute and weren’t otherwise eligible). Memberships were presented to it took Kelly 20 minutes to free him so he could be hoisted to the 2001 recipient (SN Gavino Ortiz of USCG Station South the hovering aircraft. By this time, Kelly herself was suffering Padre Island, Texas), 2002 recipient (AVT3 William Nolte of from hypothermia since her dry suit had leaked, allowing cold USCG Air Station Houston, Texas), and 2003 recipient BM1 water to enter. A second Coast Guard aircraft arrived to search Jacob Carawan of the USCGC Block Island). The first time we for the weapons officer whose body was ultimately found made the award presentation entangled in his parachute was 1991 and we have hon- about 12-feet beneath the life ored a deserving Coast Guard raft. -

The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre's 1923 And

CULTURAL EXCHANGE: THE ROLE OF STANISLAVSKY AND THE MOSCOW ART THEATRE’S 1923 AND1924 AMERICAN TOURS Cassandra M. Brooks, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Olga Velikanova, Major Professor Richard Golden, Committee Member Guy Chet, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Brooks, Cassandra M. Cultural Exchange: The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre’s 1923 and 1924 American Tours. Master of Arts (History), August 2014, 105 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. The following is a historical analysis on the Moscow Art Theatre’s (MAT) tours to the United States in 1923 and 1924, and the developments and changes that occurred in Russian and American theatre cultures as a result of those visits. Konstantin Stanislavsky, the MAT’s co-founder and director, developed the System as a new tool used to help train actors—it provided techniques employed to develop their craft and get into character. This would drastically change modern acting in Russia, the United States and throughout the world. The MAT’s first (January 2, 1923 – June 7, 1923) and second (November 23, 1923 – May 24, 1924) tours provided a vehicle for the transmission of the System. In addition, the tour itself impacted the culture of the countries involved. Thus far, the implications of the 1923 and 1924 tours have been ignored by the historians, and have mostly been briefly discussed by the theatre professionals. This thesis fills the gap in historical knowledge. -

December 2020 New Releases

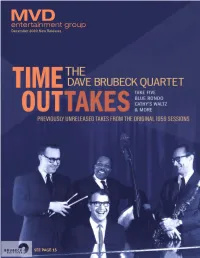

December 2020 New Releases SEE PAGE 15 what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 59 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 12 FEATURED RELEASES Video WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. THE DAVE BRUBECK THE RESIDENTS - 35 FEATURING MICK ROSSI - QUARTET - IN BETWEEN DREAMS: Film LIVE IN TOKYO TIME OUTTAKES LIVE IN SAN FRANCISCO Films & Docs 36 Faith & Family 56 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 57 Order Form 69 Deletions & Price Changes 65 TREMORS MANIAC A NIGHT IN CASABLANCA 800.888.0486 (2-DISC SPECIAL EDITION) 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 www.MVDb2b.com WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. BERT JANSCH - SUPERSUCKERS - FEATURING MICK ROSSI - BEST OF LIVE MOTHER FUCKERS BE TRIPPIN’ TIME OUT AND TAKE FIVE! LIVE IN TOKYO We could use a breather from what has been a most turbulent year, and with our December releases, we provide a respite with fantastic discoveries in the annals of cool jazz. THE DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET “TIME OUTTAKES” is an alternate version of the masterful TIME OUT 1959 LP, with the seven tracks heard for the first time in crisp, different versions with a bonus track and studio banter. The album’s “Take Five” is the biggest selling jazz single ever, and hearing this in different form is downright thrilling. On LP and CD. Also smooth jazz reigns supreme with a CD release of a newly discovered live performance from sax legend GEORGE COLEMAN. “IN BALTIMORE” is culled from a 1971 performance with detailed liner notes and rare photos. Kick Out the Jazz! Something else we could use is a release from oddball novelty song collector DR. -

Sun Valley Serenade Orchestra Wives

Sun Valley Serenade Orchestra Wives t’s funny how music can define an entire come one of Miller’s biggest hits, “Chattanooga We also get some wonderful Harry Warren and era, and Glenn Miller’s unique sound did Choo Choo,” which, in the film, is a spectacu- Mack Gordon songs, including “At Last” (the Ijust that. It is not possible to think of World lar production number with Dandridge and The castoff from Sun Valley Serenade), “Serenade War II without thinking of the Miller sound. It Nicholas Brothers. Another great new song, “At in Blue,” “People Like You and Me,” and the was everywhere – pouring out of jukeboxes, Last,” was also recorded for the film, but wasn’t instant classic, “I’ve Got a Gal in Kalamazoo.” radios, record players. Miller had been strug- used, except as background music for several The latter was, like “Chattanooga Choo Choo,” gling in the mid-1930s and was dejected, but scenes. The song itself would end up in the nominated for an Oscar for Best Song. It knew he had to come up with a unique sound next Miller film. lost to a little Irving Berlin song called “White to separate him from all the others – and, of Christmas.” course, the sound he came up with was spec- “Chattanooga Choo Choo” hit number one on tacular and the people ate it up. His song the Billboard chart in December of 1941 and George Montgomery’s trumpet playing was “Tuxedo Junction” sold 115,000 copies in one stayed there for nine weeks. The song was dubbed by Miller band member, Johnny Best week when it was released. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials ..................................................................................................................................... -

Cinema Art (November 1926)

“Worlds Greatest Phot auMLWumwe . ... )j[ JJjj1[1 , 1 Let Us Save You Money On Your Magazines Publishers’ Price Our Price for Cinema Art . $3.50 si Motion Picture Classic 2.50 All Only §1 Film Fun 2.00 Screenland 3.00 Motion Picture Magazine . 2.50 $ 14.35 E Picture Play Magazine 2. SO e Price Cosmopolitan . .$3,001 Our Collier’s .... 2,001 ^American Magazine ....$2 50] : $ e Good Housekeeping . 3.00 Pictorial Review 1.501 ^Woman's Home Com- E i $8.00 . 3.501 Soy's Life ........... $5.00 panion 1.00 Cinema Art 2.00 j- $6.50 Scientific American 4.00 f IS Our Price Cinema Art .$3.50] Regular price $5.50 *To one address 1 Harper’s Bazaar . 4.001 $8.75 Regular price $7.50) Cosmopolitan . 3.00] Good Housekeeping , $3,001 Cosmopolitan 3.00! Magazine $2,501 Cinema Art .$3,501 Our Price $5.00 American ' To one, address 1 Woman’s Home Com- McCall’s . 1.00 $5.10 Regular prifte $6.00) panion 1.00 j- $2.75 Pictorial Review . 1.50] T o c:u- address 1 * Delineator $2.00 Physical Culture .$2.50 Our Price Regular 'price $3.50) ^Everybody’s, 2.50 True Story . 2.50 $7.50 Woman '5 Home Com- Cinema Art . 3.50 $4.50 Delineator 2,001 panion T.fJO $ Everybody’s , 2.50’ McCall’s ]... ..$1,001 *To one address $3.50 To one adjdress People’s Home Journal... 1.00 Regular price $5.50 $1.50 Regular price $4.50 * Delineator Regular price $2.0oj $2.00] *Everybody’s 2,50 Fashionable Dress .$3.00] $3.60 Pathfinder ....$1,001 Little 2.001- Folks $5.25 Designer .