Theatre Archive Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

Tina Turner Said: “I First Met Aisha During Early Rehearsals for Our Show

AISHA JAWANDO TO PLAY TITLE ROLE IN T I N A - T H E T I N A T U R N E R M U S I C A L AT THE ALDWYCH THEATRE Aisha Jawando, who has been with the Company since its world premiere in Spring 2018, steps up to play the title role in TINA – THE TINA TURNER MUSICAL from 8 October 2019. Having originally played Tina’s sister Alline Bullock, Jawando has subsequently performed the iconic role of Tina at certain performances. Tina Turner said: “I first met Aisha during early rehearsals for our show. She was in our original West End Company playing my sister Alline and I loved her performance. It has been special to watch her journey with us and see the development of her extraordinary talent. I am so pleased that Aisha will now lead our company through its next chapter here in London.” Aisha Jawando said: “I have loved being part of this show from the very beginning, and I am thrilled to have the opportunity to play this exceptional role. Tina Turner is such an inspirational woman and I hope that I continue to make her proud.” Based on the life of legendary artist Tina Turner, TINA – THE TINA TURNER MUSICAL will continue its open-ended run in London at the Aldwych Theatre with new seats on sale this Autumn. Jawando takes on the leading role from Nkeki Obi-Melekwe, who will join the Broadway company later this year to play Tina at certain performances. Adrienne Warren, who originated the role here in the West End, will lead the Broadway cast. -

Silent Films of Alfred Hitchcock

The Hitchcock 9 Silent Films of Alfred Hitchcock Justin Mckinney Presented at the National Gallery of Art The Lodger (British Film Institute) and the American Film Institute Silver Theatre Alfred Hitchcock’s work in the British film industry during the silent film era has generally been overshadowed by his numerous Hollywood triumphs including Psycho (1960), Vertigo (1958), and Rebecca (1940). Part of the reason for the critical and public neglect of Hitchcock’s earliest works has been the generally poor quality of the surviving materials for these early films, ranging from Hitchcock’s directorial debut, The Pleasure Garden (1925), to his final silent film, Blackmail (1929). Due in part to the passage of over eighty years, and to the deterioration and frequent copying and duplication of prints, much of the surviving footage for these films has become damaged and offers only a dismal representation of what 1920s filmgoers would have experienced. In 2010, the British Film Institute (BFI) and the National Film Archive launched a unique restoration campaign called “Rescue the Hitchcock 9” that aimed to preserve and restore Hitchcock’s nine surviving silent films — The Pleasure Garden (1925), The Lodger (1926), Downhill (1927), Easy Virtue (1927), The Ring (1927), Champagne (1928), The Farmer’s Wife (1928), The Manxman (1929), and Blackmail (1929) — to their former glory (sadly The Mountain Eagle of 1926 remains lost). The BFI called on the general public to donate money to fund the restoration project, which, at a projected cost of £2 million, would be the largest restoration project ever conducted by the organization. Thanks to public support and a $275,000 dona- tion from Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation in conjunction with The Hollywood Foreign Press Association, the project was completed in 2012 to coincide with the London Olympics and Cultural Olympiad. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

A PSILLAS Biog Audiocraft

Sound Designer: Mr Avgoustos Psillas Avgoustos established AudioCarft Scandinavia in 2020 after 12 years at Autograph Sound in London, where he worked as a sound designer. Autograph Sound is a leading British sound design and equipment hire company, responsible for numerous theatre productions in the UK and abroad, including: Hamilton, Les Misérables, Wicked!, Mamma Mia!, Book of Mormon, Marry Poppins, Matilda, Harry Potter and the cursed child and many others. Avgoustos’ designer credits for musical theatre and theatre: The Sound of Music Stockholm Stadsteater Circus Days and Night Malmö Opera & Circus Cirkör Matilda The Musical Royal Danish Theatre Funny Girl Malmö Opera Sweeney Todd Royal Danish Opera BIG The Musical Dominion Theatre, London Blues in the Night The Kiln Theatre Matilda The Musical Malmö Opera The Ferryman St James Theatre, on Broadway, NY Kiss Me Kate Opera North, London Coliseum Pippin Malmö Opera Elf The Musical The Lowry, Manchester BIG The Musical Theatre Royal Plymouth & Bord Gais, Dublin Oliver! The Curve, Leicester AGES The Old Vic, London Pygmalion Garrick Theatre, London Strangers on a Train Gielgud Theatre, London Spamalot The Harold Pinter Theatre, London Spamalot (Remount) London Playhouse EPIDEMIC The Musical The Old Vic, London Henry V Open Air Theatre Regent’s Park Hobson’s Choice Open Air Theatre Regent’s Park Winter’s Tale Open Air Theatre Regent’s Park AudioCraft Scandinavia AB | Svanvägen 59, 611 62, Nyköping, Sweden e: [email protected] | t: +44 79 50292095 | Organisation no: 559281-2035 | VAT -

Artistic Director Rupert Goold Today Announces the Almeida Theatre’S New Season

Press release: Thursday 1 February Artistic Director Rupert Goold today announces the Almeida Theatre’s new season: • The world premiere of The Writer by Ella Hickson, directed by Blanche McIntyre. • A rare revival of Sophie Treadwell’s 1928 play Machinal, directed by Natalie Abrahami. • The UK premiere of Dance Nation, Clare Barron’s award-winning play, directed by Bijan Sheibani. • The first London run of £¥€$ (LIES) from acclaimed Belgian company Ontroerend Goed. Also announced today: • The return of the Almeida For Free festival taking place from 3 to 5 April during the run of Tennessee Williams’ Summer and Smoke. • The new cohort of eleven Resident Directors. Rupert Goold said today, “It is with enormous excitement that we announce our new season, featuring two premieres from immensely talented and ground-breaking writers, a rare UK revival of a seminal, pioneering American play, and an exhilarating interactive show from one of the most revolutionary theatre companies in Europe. “We start by welcoming back Ella Hickson, following her epic Oil in 2016, with new play The Writer, directed by Blanche McIntyre. Like Ella’s previous work, this is a hugely ambitious, deeply political play that consistently challenges what theatre can and should be. “Following The Writer, we are thrilled to present a timely revival of Sophie Treadwell’s masterpiece, Machinal, directed by Natalie Abrahami. Ninety years after it emerged from the American expressionist theatre scene and twenty-five years since its last London production, it remains strikingly resonant in its depiction of oppression, gender and power. “I first saw Belgian company Ontroerend Goed’s show £¥€$ (LIES) at the Edinburgh Fringe last year. -

Women in Theatre 2006 Survey

WOMEN IN THEATRE 2006 SURVEY Sphinx Theatre Company 2006 copyright. No part of this survey may be reproduced without permission WOMEN IN THEATRE 2006 SURVEY Sphinx Theatre Company copyright 2006. No part of this survey may be reproduced without permission The comparative employment of men and women as actors, directors and writers in the UK theatre industry, and how new writing features in venues’ programming Period 1: 16 – 29 January 2006 (inclusive) Section A: Actors, Writers, Directors and New Writing. For the two weeks covered in Period 1, there were 140 productions staged at 112 venues. Writers Of the 140 productions there were: 98 written by men 70% 13 written by women 9% 22 mixed collaboration 16% (7 unknown) 5% New Writing 48 of the 140 plays were new writing (34%). Of the 48 new plays: 30 written by men 62% 8 written by women 17% 10 mixed collaboration 21% The greatest volume of new writing was shown at Fringe venues, with 31% of its programme for the specified time period featuring new writing. New Adaptations/ New Translations 9 of the 140 plays were new adaptations/ new translations (6%). Of the 9 new adaptations/ new translations: 5 written by men 0 written by women 4 mixed collaboration 2 WOMEN IN THEATRE 2006 SURVEY Sphinx Theatre Company copyright 2006. No part of this survey may be reproduced without permission Directors 97 male directors 69% 32 female directors 23% 6 mixed collaborations 4% (5 unknown) 4% Fringe theatres employed the most female directors (9 or 32% of Fringe directors were female), while subsidised west end venues employed the highest proportion of female directors (8 or 36% were female). -

MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian

#10 silent comedy, slapstick, music hall. CONTENTS 3 DVD news 4Lost STAN LAUREL footage resurfaces 5 Comedy classes with Britain’s greatest screen co- median, WILL HAY 15 Sennett’s comedienne MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian 19 Did STAN LAUREL & LUPINO LANE almost form a team? 20 Revelations and rarities : LAUREL & HARDY, RAYMOND GRIFFITH, WALTER FORDE & more make appearances at Kennington Bioscope’s SILENT LAUGHTER SATURDAY 25The final part of our examination of CHARLEY CHASE’s career with a look at his films from 1934-40 31 SCREENING NOTES/DVD reviews: Exploring British Comedies of the 1930s . MORE ‘ACCIDENTALLY CRITERION PRESERVED’ GEMS COLLECTION MAKES UK DEBUT Ben Model’s Undercrank productions continues to be a wonderful source of rare silent comedies. Ben has two new DVDs, one out now and another due WITH HAROLD for Autumn release. ‘FOUND AT MOSTLY LOST’, presents a selection of pre- LLOYD viously lost films identified at the ‘Mostly Lost’ event at the Library of Con- gress. Amongst the most interesting are Snub Pollard’s ‘15 MINUTES’ , The celebrated Criterion Collec- George Ovey in ‘JERRY’S PERFECT DAY’, Jimmie Adams in ‘GRIEF’, Monty tion BluRays have begun being Banks in ‘IN AND OUT’ and Hank Mann in ‘THE NICKEL SNATCHER’/ ‘FOUND released in the UK, starting AT MOSTLY LOST is available now; more information is at with Harold Lloyd’s ‘SPEEDY’. www.undercrankproductions.com Extra features include a com- mentary, plus documentaries The 4th volume of the ‘ACCIDENTALLY PRESERVED’ series, showcasing on Lloyd’s making of the film ‘orphaned’ films, many of which only survive in a single print, is due soon. -

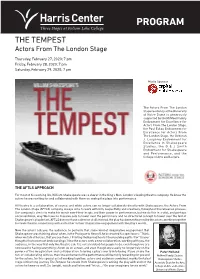

PROGRAM the TEMPEST Actors from the London Stage

PROGRAM THE TEMPEST Actors From The London Stage Thursday, February 27, 2020; 7 pm Friday, February 28, 2020; 7 pm Saturday, February 29, 2020; 7 pm Media Sponsor The Actors From The London Stage residency at the University of Notre Dame is generously supported by the McMeel Family Endowment for Excellence for Actors From The London Stage, the Paul Eulau Endowment for Excellence for Actors From The London Stage, the Deborah J. Loughrey Endowment for Excellence in Shakespeare Studies, the D & J Smith Endowment for Shakespeare and Performance, and the College of Arts and Letters. THE AFTLS APPROACH For most of his working life, William Shakespeare was a sharer in the King’s Men, London’s leading theatre company. He knew the actors he was writing for and collaborated with them on seeing the plays into performance. All theatre is a collaboration, of course, and while actors can no longer collaborate directly with Shakespeare, the Actors From The London Stage (AFTLS) company always aims to work with him, respectfully and creatively, throughout the rehearsal process. Our company’s aim is to make his words exert their magic and their power in performance, but we do this in a vital, and perhaps unconventional, way. We have no massive sets to tower over the performers and no directorial concept to tower over the text of Shakespeare’s play. In fact, AFTLS does not have a director at all; instead, the play has been rehearsed by the actors, working together to create theatre, cooperating with each other in their imaginative engagement with the play’s words. -

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Recordings are on vinyl unless marked otherwise marked (* = Cassette or # = Compact Disc) KEY OC - Original Cast TV - Television Soundtrack OBC - Original Broadway Cast ST - Film Soundtrack OLC - Original London Cast SC - Studio Cast RC - Revival Cast ## 2 (OC) 3 GUYS NAKED FROM THE WAIST DOWN (OC) 4 TO THE BAR 13 DAUGHTERS 20'S AND ALL THAT JAZZ, THE 40 YEARS ON (OC) 42ND STREET (OC) 70, GIRLS, 70 (OC) 81 PROOF 110 IN THE SHADE (OC) 1776 (OC) A A5678 - A MUSICAL FABLE ABSENT-MINDED DRAGON, THE ACE OF CLUBS (SEE NOEL COWARD) ACROSS AMERICA ACT, THE (OC) ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHHAUSEN, THE ADVENTURES OF COLORED MAN ADVENTURES OF MARCO POLO (TV) AFTER THE BALL (OLC) AIDA AIN'T MISBEHAVIN' (OC) AIN'T SUPPOSED TO DIE A NATURAL DEATH ALADD/THE DRAGON (BAG-A-TALE) Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection ALADDIN (OLC) ALADDIN (OC Wilson) ALI BABBA & THE FORTY THIEVES ALICE IN WONDERLAND (JANE POWELL) ALICE IN WONDERLAND (ANN STEPHENS) ALIVE AND WELL (EARL ROBINSON) ALLADIN AND HIS WONDERFUL LAMP ALL ABOUT LIFE ALL AMERICAN (OC) ALL FACES WEST (10") THE ALL NIGHT STRUT! ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS (TV) ALL IN LOVE (OC) ALLEGRO (0C) THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN AMBASSADOR AMERICAN HEROES AN AMERICAN POEM AMERICANS OR LAST TANGO IN HUAHUATENANGO .....................(SF MIME TROUPE) (See FACTWINO) AMY THE ANASTASIA AFFAIRE (CD) AND SO TO BED (SEE VIVIAN ELLIS) AND THE WORLD GOES 'ROUND (CD) AND THEN WE WROTE... (FLANDERS & SWANN) AMERICAN -

Black and Asian Theatre in Britain a History

Black and Asian Theatre in Britain A History Edited by Colin Chambers First published 2011 ISBN 13: 978-0-415-36513-0 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978-0-415-37598-6 (pbk) Chapter 8 ‘All a we is English’ Colin Chambers CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 8 ‘All A WE IS English’1 Britain under Conservative rule in the 1980s and for much of the 1990s saw black and Asian theatre wax and then wane, its growth the result of earlier forces’ coming to a head and its falling away a consequence of cuts allied to a state-driven cultural project that celebrated the individual over the collective and gave renewed impetus to aggressive, narrow nationalism. How to survive while simultaneously asserting the heterodox, hybrid nature of non-white theatre and its contribution to British theatre was the urgent challenge. Within two years of the Thatcher government’s election to power in 1979, Britain saw perhaps the most serious rioting of its postwar era, which led to major developments in public diversity policy, though less significant change at the level of delivery. The black community could no longer be taken for granted and was demanding its rights as British citizens. The theatre group that epitomized this new urgency and resilience and the need to adapt to survive was the Black Theatre Co-operative (BTC).2 The group was founded by Mustapha Matura and white director Charlie Hanson in 1978 after Hanson had failed to interest any theatres in Welcome Home Jacko, despite Matura’s standing as the leading black playwright of his generation. -

Fred Tomlin (Boom Operator) 1908 - ? by Admin — Last Modified Jul 27, 2008 02:45 PM

Fred Tomlin (boom operator) 1908 - ? by admin — last modified Jul 27, 2008 02:45 PM BIOGRAPHY: Fred Tomlin was born in 1908 in Hoxton, London, just around the corner from what became the Gainsborough Film Studios (Islington) in Poole Street. He first visited the studio as a child during the filming of Woman to Woman (1923). He entered the film industry as an electrician, working in a variety of studios including Wembley, Cricklewood and Islington. At Shepherd’s Bush studio he got his first experience as a boom operator, on I Was A Spy (1933). Tomlin claims that from that point until his retirement he was never out of work, but also that he was never under permanent contract to any studio, working instead on a freelance basis. During the 1930s he worked largely for Gaumont and Gainsborough on films such as The Constant Nymph (1933), Jew Suss (1934), My Old Dutch (1934), and on the Will Hay comedies, including Oh, Mr Porter (1937) and Windbag the Sailor (1936). During the war, Tomlin served in the army, and on his return continued to work as a boom operator on films and television (often alongside Leslie Hammond) until the mid 1970s. His credits include several films for Joseph Losey (on Boom (1968) and Secret Ceremony (1968)) and The Sea Gull (1968)for Sidney Lumet, as well as TV series such as Robin Hood and The Buccaneers and a documentary made in Cuba for Granada TV. SUMMARY: In this interview from 1990, Tomlin talks to Bob Allen about his career, concentrating mainly on the pre-war period.