MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPRING 2011.Pdf

THE INTERNET NOISELETTER OF LOOSER THAN LOOSE SPRING VOLUME Nº 5 2011 Vintage Entertainment ISSUE Nº 11 THIS WEB-DOC IS ABSOLUTELY FREE OF CHARGE looser than loose publishing loose cannon fire www.looserthanloose.com A Rambling Editorial Screed by Dave Stevenson All Original Material © 2011 Today’s Editorial is Brought to you by the Letter Troll DITED UBLISHED Y Once upon a time, American popular culture spawned a maniacal, nar- E DITED & PUBLISHED BY cissistic freak-show of a man who was thought by many to be a genius, but Dave and Ali Stevenson known to everyone as a perilously unstable lunatic. He chain-smoked 188 Seames Drive, Marlboro cigarettes, swilled bourbon like water and had a reputation for Manchester, NH 03103 U.S.A. abusing recreational drugs. He was known to associate with the worst kind [email protected] of reprobates, misfits and malcontents - often leading to violent or con- frontational situations. His manner of speaking seemed to be the product LAYOUT & DESIGN of a racing mind and was characterized by a twisted kind of logic that even he would describe as being dangerously insane. No, his name is not Charlie Dave Stevenson Sheen. It was Hunter S. Thompson - a formerly inimitable figure whose DISTRIBUTIONISTRIBUTION once-unique troubles have now seemingly found their way into Sheen’s consciousness. At least, for commercial purposes. Ali Stevenson In recent days, Charlie Sheen has spent his spare time amusing us with DEADLINE FOR VOL. 5, ISSUE Nº 12: a new kind of Punch and Judy show. The cast is comprised of his ego May 1, 2011 (Punch) and his less-than-appreciable acting skills (Judy). -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

2006 Thelma Todd Celebration

Slapstick Magazine Presents 2006 Thelma Todd Celebration July 27 - July 30 Manchester, New Hampshire Join us as we celebrate the centenary of Thelma Todd, the Merrimack Valley’s queen of comedy Film Program As we draw nearer to the event, additional titles are likely to become available. Accordingly, the roster below may see some minor changes. There is ample free parking at UNH. THURSDAY, July 27th Fay Tincher - Ethel’s Roof Party UNH Hall, Commercial Street, Manchester Mabel Normand - A Muddy Romance (All titles in 16mm except where noted) Alice Howell - One Wet Night Wanda Wiley - Flying Wheels AM Edna Marian - Uncle Tom’s Gal 9:00 Morning Cartoon Hour 1 Gale Henry - Soup to Nuts Rare silent/sound cartoons Mary Ann Jackson - Smith’s Candy Shop 10:00 Charley Chase Silents (fragment) What Women Did for Me Anita Garvin/Marion Byron - A Pair of Tights Hello Baby ZaSu Pitts/Thelma Todd - One Track Minds Mama Behave (also features Spanky McFarland) A Ten Minute Egg 11:00 Larry Semon Shorts 9:30 Shaskeen Irish Pub, 909 Elm Street (directly across Titles TBA till from City Hall) 12:00 LUNCH (1 hour) close Silent and sound shorts featuring: Laurel and Hardy PM W.C. Fields 1:00 ZaSu Pitts - Thelma Todd Shorts Buster Keaton The Pajama Party The Three Stooges Seal Skins Asleep in the Feet 2:00 Snub Pollard and Jimmy Parrott FRIDAY, July 28th Sold at Auction (Pollard) UNH Hall, Commercial Street, Manchester Fully Insured (Pollard) (All titles in 16mm except where noted) Pardon Me (Pollard) AM Between Meals (Parrott) 9:00 Morning Cartoon Hour 2 -

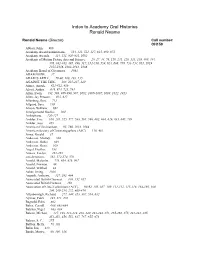

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame Ronald Neame (Director) Call number: OH159 Abbott, John, 906 Academy Award nominations, 314, 321, 511, 517, 935, 969, 971 Academy Awards, 314, 511, 950-951, 1002 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science, 20, 27, 44, 76, 110, 241, 328, 333, 339, 400, 444, 476, 482-483, 495, 498, 517, 552-556, 559, 624, 686, 709, 733-734, 951, 1019, 1055-1056, 1083-1084, 1086 Academy Board of Governors, 1083 ADAM BEDE, 37 ADAM’S APPLE, 79-80, 100, 103, 135 AGAINST THE TIDE, 184, 225-227, 229 Aimee, Anouk, 611-612, 959 Alcott, Arthur, 648, 674, 725, 784 Allen, Irwin, 391, 508, 986-990, 997, 1002, 1006-1007, 1009, 1012, 1013 Allen, Jay Presson, 925, 927 Allenberg, Bert, 713 Allgood, Sara, 239 Alwyn, William, 692 Amalgamated Studios, 209 Ambiphone, 126-127 Ambler, Eric, 166, 201, 525, 577, 588, 595, 598, 602, 604, 626, 635, 645, 709 Ambler, Joss, 265 American Film Institute, 95, 766, 1019, 1084 American Society of Cinematogaphers (ASC), 118, 481 Ames, Gerald, 37 Anderson, Mickey, 366 Anderson, Robin, 893 Anderson, Rona, 929 Angel, Heather, 193 Ankers, Evelyn, 261-263 anti-Semitism, 562, 572-574, 576 Arnold, Malcolm, 773, 864, 876, 907 Arnold, Norman, 88 Arnold, Wilfred, 88 Asher, Irving, 1026 Asquith, Anthony, 127, 292, 404 Associated British Cinemas, 108, 152, 857 Associated British Pictures, 150 Association of Cine-Technicians (ACT), 90-92, 105, 107, 109, 111-112, 115-118, 164-166, 180, 200, 209-210, 272, 469-470 Attenborough, Richard, 277, 340, 353, 387, 554, 632 Aylmer, Felix, 185, 271, 278 Bagnold, Edin, 862 Baker, Carroll, 680, 883-884 Balchin, Nigel, 683, 684 Balcon, Michael, 127, 198, 212-214, 238, 240, 243-244, 251, 265-266, 275, 281-282, 285, 451-453, 456, 552, 637, 767, 855, 878 Balcon, S. -

The Three Stooges

DERDE JAARGANG The Three Stooges Maart 2016 1 Film Fun Film Fun is een tijdschrift van Thys Ockersen dat maandelijks verschijnt en geleverd wordt aan een select gezelschap geïnteresseerden. De Film Fun-uitgaven zijn te downloaden op thysockersenfilms.com onder de noemer FILM FUN. ©2016: Thys Ockersen Films/ FILM FUN i Dit is nummer 27 3e jaargang maart 2016 i Tekst en foto’s: Thys Ockersen/Still-photo Gastredacteuren: Jan Meng, Thomas Leeflang Vormgeving: Hille Tymstra Thys Ockersen Films Wilhelminaweg 54 2042NR ZANDVOORT Tel: 0611599953 thysockersenfilms.com [email protected] Film Fun is zo opgemaakt dat twee pagina’s naast elkaar het prettigst aandoen bij het lezen. 2 Film Fun #27 The Three Stooges ABSURDISME OP HOOG NIVEAU ‘Ik doe in m’n films soms iets waarvan ik later denk: hé, dat zag ik bij de Stooges! Het zijn mijn ‘cult heroes’. Ze zijn leuk, ze zijn groots en ze zijn tijdloos. De Drie Stooges verouderen nooit omdat hun humor van alle tijden is.’ Whoopi Goldberg in 1987 in The Three Stooges Book of Scripts Je houdt van ze, of je haat ze: Channel 11, een station dat The Three Stooges (De Drie Thomas Leeflang elke middag ‘reruns’ van De Stoethaspels). De liefde is Drie Stooges uitzond. In een echter vele malen groter dan voorwoord in het Three Stoo- de haat. Ze zijn meer dan populair bij mil- ges Book of Scripts uit 1987 zei Whoopi Gold- joenen fans ‘all over the world’; liefhebbers berg: ‘De Stooges werkten perfect samen en treffen elkaar via legio Stooges-websites. Het hadden een geweldig gevoel voor timing. -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism. -

![It Happened in Hollywood (Comedians) (1960) [Screen Gems] [Sound] Hosted by Vincent Price](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6219/it-happened-in-hollywood-comedians-1960-screen-gems-sound-hosted-by-vincent-price-1186219.webp)

It Happened in Hollywood (Comedians) (1960) [Screen Gems] [Sound] Hosted by Vincent Price

JOHN E. ALLEN, INC. JEA T.O.16 <05/95> [u-bit #19200037] 16:00:07 -It Happened In Hollywood (Comedians) (1960) [Screen Gems] [sound] hosted by Vincent Price AERIAL of Hollywood, HA houses and buildings, street scenes, sign: “Hollywood & Vine”, court of Graumans Chinese Theatre with Vincent Price looking at hand and foot prints (1960) Henry B. Walthall in early Western with Harry Carey, Ken Murray with Buster Keaton and Billy Gilbert and Joan Davis in pie throwing sequence, Vincent Price’s home, collection of masks, Price looking at film clips through movieola (1960) John Bunny and Flora Finch, Mack Sennett, Charlie Murray with Fatty Arbuckle and Sessue Hayakawa, Harold Lloyd, Chester Conklin, Clyde Cook on roller skates in restaurant, Zasu Pitts in front of cameraman cranking movie camera, Louise Fazenda giving apple to director Erie Kenton with cameraman loading camera, Jimmy Durante, Marx Brothers and Syd Graumans, Ritz Brothers, W.C. Fields hitting golf ball, Price changing reel on movieola (1960) Ken Murray and ladies on bicycle built for three, Fred Allen and Rudy Vallee speaking into NBC microphone on radio show, CUT AWAY of audience laughing, Bob Hope with Brenda and Cobina speaking into microphone, Mickey Rooney watching himself as Mickey McGuire with Mary Pickford and Ruth Roland and Mae Murray and Dolores Del Rio and June Kaiser, Douglas Fairbanks with Joel McCrea, straw hat signed by Maurice Chevalier 16:16:22 Groucho Marx and Carole Landis with dark hair singing western songs into microphone with orchestra in background for WWII U.S. soldiers 16:18:25 Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis at Photo Play award dinner with George Jessel -16:24:38 16:24:48 -It Happened In Hollywood (Westerns) (1960) [Screen Gems] [sound] hosted by Vincent Price Vincent Price speaking from western set on back lot of movie studio, looking at film clips on movieola (1960) MCU William S. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Ask a Policeman Free

FREE ASK A POLICEMAN PDF The Detection Club,Agatha Christie,Dorothy L. Sayers,Anthony Berkeley,Gladys Mitchell,Helen Simpson | 336 pages | 08 Nov 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007468621 | English | London, United Kingdom Ask a Policeman () directed by Marcel Varnel • Reviews, film + cast • Letterboxd The mirthful adventures of Police-Sergeant Samuel Dudfoot and his Ask a Policeman constables, Albert Brown and Jeremias Harbottle, who stage a fabricated crime-wave to save their jobsand then find themselves involved in the real thing. Derick Williams Jack Parry. Will Hay and his incompetent gang as village coppers! No other outcome then a comedy classic is possible! And might perhaps be Hay's Ask a Policeman too? The village of Turnbotham Round has the reputation of being the safest place in England with not a single crime committed in 10 years 4 months and 5 days. Which just happens to be the exact same amount of time that Sergeant Samuel Dudfoot Will Hay has been in charge of the local police station. Unfortunately when that information comes to the attention of the Chief Constable he threatens to close the station down and put Dudfoot and his two constables out of work, so it now falls to them to come up with some crime. Luckily, and unsurprisingly, the very thing they need has Ask a Policeman going on under their noses for at least the last 10 years 4 months…. This is a hugely enjoyable yarn about three incompetent and Ask a Policeman bent coppers who somehow manage to thwart a major smuggling operation. This is a lot of fun, I've liked Will Hay comedies since I first saw them as a boy, and this one Ask a Policeman solid, with snappy, amusing dialogue from the shady, but good-hearted, boys. -

Noel Drewe Collection Film 178D5

Noel Drewe Collection Film 178D5 178D5.1 Outlook Very Black 9.5mm, Safety Film, Pathescope Noel Drewe Brittle Noel Drewe Collection 178D5.2 Monkeyland 9.5mm Noel Drewe Brittle, perforation damage Noel Drewe Collection 178D5.3 Fun at the Circus 9.5mm, Pathescope Noel Drewe , Circusama, Yesterday Circus Today Circus Noel Drewe Collection 178D5.4 At the Circus 9.5mm, Pathescope Noel Drewe, Circusama, Yesterday Circus Today Circus 2 Reels. Sound. Featuring "Circus Karo". Includes trapeze, whip act and 'sea lions'. Original sound commentary by Geoffrey Sumner. Supplied by C. W. Cramp Noel Drewe Collection 178D5.5 A Man-Sized Pet 9.5mm, Pathescope Noel Drewe, Circusama, Yesterday Circus Today Supplied by C. W. Cramp Noel Drewe Collection 178D5.6 A Fresh Start 300 feet 12 mins 9.5mm, Pathescope Noel Drewe, Circusama, Yesterday Circus Today Brittle, box rust transfer Adams, Jimmy Noel Drewe Collection 178D5.7 Circus at the Zoo 300 feet 12 mins 9.5mm, Pathescope Noel Drewe, Circusama, Yesterday Circus Today Brittle Circus USA Silent. Includes chimps Noel Drewe Collection 178D5.8 Circus Comes to Town 400 feet Harris, Ron 16 mins 9.5mm, Pathescope Noel Drewe, Circusama, Yesterday Circus Today Circus Silent. Features Belle Vue circus On box ‘This film purchased from Ilkeston Cine Service Supplied by C. W. Cramp Noel Drewe Collection 178D5.9 Circus Stedman of Leeds Holdings of Blackburn Ltd Cine and photographic Suppliers 9.5mm, Pathescope Noel Drewe, Circusama, Yesterday Circus Today Circus Bertram Mills Silent. Includes King George VI and Queen Elizabeth’s coronation, so the circus must be 1936/37. -

TPTV Schedule September 24Th - 30Th 2018

TPTV Schedule September 24th - 30th 2018 DATE TIME PROGRAMME SYNOPSIS Mon 24 6:00 Piccadilly Incident 1946. War. Director: Herbert Wilcox. Stars Anna Neagle, Michael Wilding, Sep 18 Coral Browne & Edward Rigby. A missing Wren returns from a desert isle and finds her husband has a new wife and son. Mon 24 8:00 Hawkeye & the Way Station. 1957. Directed by Sam Newfield. Stars John Hart, Lon Sep 18 Last of the Chaney Jr & James Doohan. The daughter of Mingo Chief Nocona is Mohicans desired by two warring tribesmen. (Subtitles Available) Mon 24 8:30 Convict 99 1938. Comedy. Directed by Marcel Varnel. Stars Will Hay, Moore Marriott, Sep 18 Graham Moffat & Googie Withers. A school master is mistaken for a prison governor and assigned the charge of a prison. Mon 24 10:15 Glimpses of Glimpses: Made as an educational film showing our crops of hops & fruit. Sep 18 Southern England The film provides a startling glimpses of bygone days of all of the in 1968 Southern area of the UK including great aerial shots. Mon 24 10:35 The Lost Moment 1947. Drama. A publisher insinuates himself into the mansion of the Sep 18 centenarian lover of a renowned but long-dead poet in order to find his lost love letters. Starring Robert Cummings & Susan Hayward. Mon 24 12:20 Waterloo Road 1944. Drama. Director: Sidney Gilliat. Stars Stewart Granger, John Mills, Sep 18 Alastair Sim & Joy Shelton. After Jim reports for military duty, he suspects that his bride has been seeing another man. Mon 24 13:55 The Old Dark 1963. -

Dr. Strangelove's America

Dr. Strangelove’s America Literature and the Visual Arts in the Atomic Age Lecturer: Priv.-Doz. Dr. Stefan L. Brandt, Guest Professor Room: AR-H 204 Office Hours: Wednesdays 4-6 pm Term: Summer 2011 Course Type: Lecture Series (Vorlesung) Selected Bibliography Non-Fiction A Abrams, Murray H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. Seventh Edition. Fort Worth, Philadelphia, et al: Harcourt Brace College Publ., 1999. Abrams, Nathan, and Julie Hughes, eds. Containing America: Cultural Production and Consumption in the Fifties America. Birmingham, UK: University of Birmingham Press, 2000. Adler, Kathleen, and Marcia Pointon, eds. The Body Imaged. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993. Alexander, Charles C. Holding the Line: The Eisenhower Era, 1952-1961. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana Univ. Press, 1975. Allen, Donald M., ed. The New American Poetry, 1945-1960. New York: Grove Press, 1960. ——, and Warren Tallman, eds. Poetics of the New American Poetry. New York: Grove Press, 1973. Allen, Richard. Projecting Illusion: Film Spectatorship and the Impression of Reality. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997. Allsop, Kenneth. The Angry Decade: A Survey of the Cultural Revolt of the Nineteen-Fifties. [1958]. London: Peter Owen Limited, 1964. Ambrose, Stephen E. Eisenhower: The President. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984. “Anatomic Bomb: Starlet Linda Christians brings the new atomic age to Hollywood.” Life 3 Sept. 1945: 53. Anderson, Christopher. Hollywood TV: The Studio System in the Fifties. Austin: Univ. of Texas Press, 1994. Anderson, Jack, and Ronald May. McCarthy: the Man, the Senator, the ‘Ism’. Boston: Beacon Press, 1952. Anderson, Lindsay. “The Last Sequence of On the Waterfront.” Sight and Sound Jan.-Mar.