Argentina Missing Bones.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring the Role of Epistemic Communities in Nuclear Non-Proliferation Outcomes

Politics & The Bomb: Exploring the Role of Epistemic Communities in Nuclear Non-Proliferation Outcomes. Sara Zahra Kutchesfahani UCL Department of Political Science Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science October 2010 DECLARATION I, Sara Zahra Kutchesfahani, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Sara Zahra Kutchesfahani ii ABSTRACT The role of epistemic communities in influencing policy formulation is underexplored in International Relations theory in general and in nuclear non-proliferation studies in particular. This thesis explores how epistemic communities – groups of experts knowledgeable in niche issue areas – have affected nuclear non-proliferation policy formulation in two important and under-studied cases: the Brazilian-Argentine Agency for Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials (ABACC) and the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) Program. It demonstrates that applying an epistemic community approach provides explanatory power heretofore lacking in explanations of these cases’ origins. The thesis applies the epistemic community framework to non-proliferation, using Haas’ (1992) seminal exploration of epistemic communities in the context of natural scientific and environmental policies. Specifically, it analyses the creation and successful implementation of ABACC and the CTR Program, which, respectively, verified the non-nuclear weapon status of Argentina and Brazil and facilitated the denuclearisation of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine. These cooperative nuclear non- proliferation agreements are shown to be the result of a process involving substantial input and direction from experts constituting epistemic communities. The thesis explores the differences in the emergence, composition, and influence mechanisms of the epistemic communities behind ABACC and the CTR Program. -

The 'Argentine Problem' : an Analysis of Political Instability in a Modern Society

THE 'ARGENTINE PROBLEM7: AN ANALYSIS OF POLITICAL INSTABILITY IN A MODERN SOCIETY Alphonse Victor Mallette B.A., University of Lethbridge, 1980 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS @ Alphonse Victor Mallette 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY June, 1986 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, proJect or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for flnanclal gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay Author: -. - rJ (date) -.-.--ABSTRACT This thesis is designed to explain, through political and historical analysis, a phenomenon identified by scholars of pol- itical development as the "Argentine Problem". Argentina is seen as a paradox, a nation which does not display the political stab- ility commensurate with its level of socio-economic development. The work also seeks to examine the origins and policies of the most serious manifestation of dictatorial rule in the nation's history, the period of military power from 1976 to 1983. -

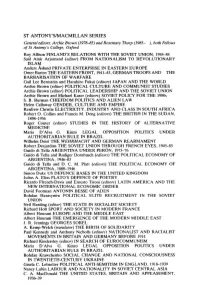

St Antony's/Macmillan Series

ST ANTONY'S/MACMILLAN SERIES General editors: Archie Brown (1978-85) and Rosemary Thorp (1985- ), both Fellows of St Antony's College, Oxford Roy Allison FINLAND'S RELATIONS WITH THE SOVIET UNION, 1944-84 Said Amir Arjomand (editor) FROM NATIONALISM TO REVOLUTIONARY ISLAM Anders Åslund PRIVATE ENTERPRISE IN EASTERN EUROPE Orner Bartov THE EASTERN FRONT, 1941-45, GERMAN TROOPS AND THE BARBARISATION OF WARFARE Gail Lee Bernstein and Haruhiro Fukui (editors) JAPAN AND THE WORLD Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL CULTURE AND COMMUNIST STUDIES Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND THE SOVIET UNION Archie Brown and Michael Kaser (editors) SOVIET POLICY FOR THE 1980s S. B. Burman CHIEFDOM POLITICS AND ALIEN LAW Helen Callaway GENDER, CULTURE AND EMPIRE Renfrew Christie ELECTRICITY, INDUSTRY AND CLASS IN SOUTH AFRICA Robert O. Collins and FrancisM. Deng (editors) THE BRITISH IN THE SUDAN, 1898-1956 Roger Couter (editor) STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE Maria D'Alva G. Kinzo LEGAL OPPOSITION POLITICS UNDER AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN BRAZIL Wilhelm Deist THE WEHRMACHT AND GERMAN REARMAMENT Robert Desjardins THE SOVIET UNION THROUGH FRENCH EYES, 1945-85 Guido di Tella ARGENTINA UNDER PERÓN, 1973-76 Guido di Tella and Rudiger Dornbusch (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1946-83 Guido di Tella and D. C. M. Platt (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1880-1946 Simon Duke US DEFENCE BASES IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Julius A. Elias PLATO'S DEFENCE OF POETRY Ricardo Ffrench-Davis and Ernesto Tironi (editors) LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC ORDER David Footman ANTONIN BESSE OF ADEN Bohdan Harasymiw POLITICAL ELITE RECRUITMENT IN THE SOVIET UNION Neil Harding (editor) THE STATE IN SOCIALIST SOCIETY Richard Holt SPORT AND SOCIETY IN MODERN FRANCE Albert Hourani EUROPE AND THE MIDDLE EAST Albert Hourani THE EMERGENCE OF THE MODERN MIDDLE EAST J. -

Según Lo Expuesto En Los Textos De Verónica Beyreuther Y Luis A

Según lo expuesto en los textos de Verónica El gobierno de la Revolución Libertadora se originó en un Beyreuther y Luis A. Romero, la llamada Revolución F golpe de Estado que terminó con el gobierno de Perón, Libertadora (1955-1958), debería ser considerada que había sido democráticamente electo. como parte de un régimen político semidemocrático. Luis A. Romero sostiene que en 1957 la Revolución Libertadora empezó a organizar su retiro y restablecer F La Libertadora había proscripto al peronismo la democracia con apoyo peronista Luis A. Romero sostiene que el poder del presidente Los votos eran prestados y las FFAA no confiaban en él V Arturo Frondizi (1958-1962) era precario por su acuerdo con Perón Al asumir la presidencia, el presidente Frondizi cumplió Frondizi sólo buscó obtener los votos que Perón podía el acuerdo que había hecho con Perón para conseguir F aportarle para ganar las elecciones. Una vez en el poder, su apoyo electoral no levantó las proscripciones como había prometido. Según Romero la política económica del gobierno de El gobierno de Illia puso especial énfasis en políticas Arturo Illia combinaba criterios básicos del populismo V económicas de redistribución y apoyo al mercado interno. reformista con elementos keynesianos. Según Luis A. Romero, el dominio de Vandor sobre sindicatos y organizaciones políticas peronistas lo llevó F Vandor pretendía institucionalizar al peronismo sin Perón. al sometimiento a Perón Según Luis A Romero el gobierno de la Revolución Argentina (1966-1973) se inició con un shock V Se disolvió el parlamento y los partidos políticos autoritario Según Luis Alberto Romero el Cordobazo (1969) fue Fue el episodio fundador de una ola de movilización social generador de cambios en la participación política y V y del nacimiento de un nuevo activismo sindical social Según Luis A. -

La Descomposición Del Poder Militar En La Argentina. Las Fuerzas Armadas Durante Las Presidencias De Galtieri, Bignone Y Alfonsín (1981-1987)∗

La descomposición del poder militar en la Argentina. Las Fuerzas Armadas durante las presidencias de Galtieri, Bignone y Alfonsín (1981-1987)∗ Paula Canelo No existen en la historia de los hombres paréntesis inexplicables. Y es precisamente en los períodos de “excepción”, en esos momentos molestos y desagradables que las sociedades pretenden olvidar, colocar entre paréntesis, donde aparecen sin mediaciones ni atenuantes, los secretos y las vergüenzas del poder cotidiano. Pilar Calveiro (1998) Introducción La normalidad nada prueba, la excepción, todo. Es en los períodos de crisis de las pautas normales de desenvolvimiento de las sociedades donde es posible encontrar los fundamentos mismos de la normalidad; es allí, en los momentos donde el poder tambalea, donde se revelan los criterios “normales” del ejercicio del poder. La última dictadura militar, autodenominada “Proceso de Reorganización Nacional” constituyó, en efecto, un momento de excepción y de quiebre en el devenir histórico de la sociedad argentina. Durante su período de máximo poderío, el correspondiente a la primera presidencia del general Videla (1976-1978), el régimen logró concretar gran parte de sus objetivos refundacionales mediante la implementación del terrorismo estatal y de la política económica del ministro Martínez de Hoz. Sostenida por un férreo aislamiento de la misma sociedad sobre la que implementaba la política represiva más devastadora de la historia argentina, y cohesionada tras la construcción de un enemigo “subversivo” omnipresente, la alianza cívico-militar que llevó adelante el proyecto dictatorial avanzó significativamente en la desarticulación de la sociedad de posguerra. Sin embargo, lejos de conformar un todo monolítico, la contradictoria alianza entre militares y civiles liberales comenzó a demostrar síntomas de agotamiento a poco de andar. -

La Argentina

LA ARGENTINA NAME: República Argentina POPULATION: 43,350,000 ETHNIC GROUPS: White (97%; Spanish and Italian mostly); Mestizo (2%); Amerindian (1%) La Argentina —1— CAPITAL: Buenos Aires (13,500,000) Other cities: Córdoba (1,500,000); Rosario (1,200,000) LANGUAGES: Spanish (official) RELIGION: Roman Catholic (90%) LIFE EXPECTANCY: Men (68); women (75) LITERACY: 97% GOVERNMENT: Democratic republic President: Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (since May 2007) MILITARY: 67,300 active troops ECONOMY: food processing (meat), autos, chemicals, grains, crude oil MONEY: peso (1.0 = $1.00 US) GEOGRAPHY: Atlantic coast down to tip of South America; second largest country in South America; Andean mountains on west; Aconcagua, highest peak in S. America (22,834 ft.); Pampas in center; Gran Chaco in north; Río de la Plata estuary (mostly fresh water from Paraná and Uruguay Rivers) HISTORY: Prehistory Nomadic Amerindians (hunter gatherers); most died by 19th century 1516 Juan de Solís discovered Argentina and claimed it for Spain 1536 Buenos Aires founded by Pedro de Mendoza; 1580 Buenos Aires refounded by Juan de Garay 1776 Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata created (Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia). 1778-1850 José de San Martín, born in Buenos Aires, liberator of cono sur; criollo (Spanish military father) raised in Spain. 1805-1851 Esteban Echeverría (writer): father of Latin American romanticism; author of El matadero (essay against Rosas). 1806 Great Britain‟s forces occupy port of Buenos Aires demanding free trade; porteños expel English troops; criollo porteños gain self- confidence. 1810 (May 25) A cabildo abierto of criollos assumes power for Fernando VII; cabildo divided between unitarios (liberals for centralized power) and federalistas (conservatives for federated republic with power in provinces). -

Pablo Miguel Jacovkis

Proof Copy Pablo Miguel Jacovkis Introduction Argentina has a long tradition of conflicts between scientific development2 (or educational development) and authoritarian governments.3 Between 1835 and 1852, although he was only Governor of the Buenos Aires Province and responsible for Argentinian Foreign Affairs – that is, a sort of primus inter pares amongst the other thirteen governors – General Juan Manuel de Rosas ruled the country with an iron fist. Among his obscurantist measures we may mention that he stopped paying salaries to the professors at the University of Buenos Aires – the salaries having to be paid exclusively through the tuition of the students, see Buchbinder (2005). The simplified image is reasonably true, that from the establishment of the constitutional republic between 1852 and 1862, education and support for science flourished. We can mention the outstanding work of President Sarmiento (1868–74), who, besides strongly backing 1 The author thanks Amparo Gómez for her kind invitation to participate in the IV Seminar of Politics of Science: Science between Democracy and Dictatorship at the Universidad de La Laguna and to the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation for its economic support through the Research Project FFI2009–09483 and the Complementary Action FFI2010–11969–E. He also thanks Rosita Wachenchauzer and Israel Lotersztain for their comments and observations, and also Amparo Gómez and Antonio Fco. Canales and, especially, Brian Balmer, for their careful review and criticisms of this work, although of course none of them is responsible for the opinions here expressed. 2 In this work we shall focus on natural and exact sciences, without mentioning social sciences and humanities. -

Presidentes Argentinos

Presidentes argentinos Período P O D E R E J E C U T I V O Presidente: BERNARDINO RIVADAVIA 1826-1827 Sin vicepresidente Presidente: JUSTO JOSÉ DE URQUIZA 1654-1860 Vicepresidente: SALVADOR MARÍA DEL CARRIL Presidente: SANTIAGO DERQUI Vicepresidente: JUAN ESTEBAN PEDERNERA 1860-1862 Derqui renunció y Pedernera, en ejercicio de la presidencia, declaró disuelto al gobierno nacional. Presidente: BARTOLOMÉ MITRE 1862-1868 Vicepresidente: MARCOS PAZ Presidente: DOMINGO FAUSTINO SARMIENTO 1868-1874 Vicepresidente: ADOLFO ALSINA Presidente: NICOLÁS AVELLANEDA 1874-1880 Vicepresidente: MARIANO AGOSTA Presidente: JULIO ARGENTINO ROCA 1880-1886 Vicepresidente: FRANCISCO MADERO Presidente: MIGUEL JUÁREZ CELMAN Vicepresidente: CARLOS PELLEGRINI 1886-1892 En 1890, Juárez Celman debió renunciar como consecuencia de la Revolución del '90. Pellegrini asumió la presidencia hasta completar el período. Presidente: LUIS SAENZ PEÑA Vicepresidente: JOSÉ EVARISTO URIBURU 1892-1898 En 1895, Luis Sáenz Peña renunció, asumiendo la presidencia URIBURU hasta culminar el período. Presidente: JULIO ARGENTINO ROCA 1898-1904 Vicepresidente: NORBERTO QUIRNO COSTA Presidente: MANUEL QUINTANA Vicepresidente: JOSÉ FIGUEROA ALCORTA 1904-1910 En 1906, Manuel Quintana falleció, por lo que debió terminar el período Figueroa Alcorta. Presidente: ROQUE SAENZ PEÑA 1910-1916 Vicepresidente: VICTORINO DE LA PLAZA En 1914, fallece Sáenz Peña, y completa el período Victorino de la Plaza Presidente: HIPÓLITO YRIGOYEN 1916-1922 Vicepresidente: PELAGIO LUNA Presidente: MARCELO TORCUATO DE ALVEAR 1922-1928 Vicepresidente: ELPIDIO GONZÁLEZ Presidente: HIPÓLITO YRIGOYEN 1928-1930 Vicepresidente: ENRIQUE MARTÍNEZ P O R T A L U N O A R G E N T I N A El 6 de setiembre de 1930 se produce el primer golpe de Estado en este período constitucional en la Argentina, por el cual se derroca a Yrigoyen. -

Former Argentine President Jailed for Crimes Against Humanity

FORMER ARGENTINE PRESIDENT JAILED FOR CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY Reynaldo Bignone served as de facto president of Argentina in 1982 and 1983 21 April 2010 Amnesty International has welcomed the prison sentence handed to a former Argentine president responsible for crimes against humanity in the 1970s. Reynaldo Bignone, a former military general, was found guilty of torture, murder and several kidnappings that occurred while he was commander of the notorious Campo de Mayo detention centre between 1976 and 1978. The 82-year-old, who was appointed de facto president of Argentina by the military junta in 1982, has been sentenced to 25 years in jail. Five other military officers were also given long jail sentences by a court in Buenos Aires province on Wednesday. "This judgement represents another important step in the fight against impunity that has, until recently, been enjoyed by the leaders of Argentina's military regime - now infamous for their role in human rights abuses,” said Guadalupe Marengo, Amnesty International's Americas Deputy Director. Hundreds of people, including relatives of the victims, testified at the trial, which started in November 2009. Former military officers Santiago Omar Riveros and Fernando Exequiel Verplaetsen were also sentenced to 25 years in prison, while three others were sentenced to between 17 and 20- years for human rights violations. A former police officer was acquitted. Campo de Mayo was one of the largest clandestine camps in operation under Argentina's military regime (1976 to 1983). It is estimated that 5,000 prisoners were held in the camp. "Victims of torture and enforced disappearance in Campo de Mayo have waited too long for justice. -

Presidents of Latin American States Since 1900

Presidents of Latin American States since 1900 ARGENTINA IX9X-1904 Gen Julio Argentino Roca Elite co-option (PN) IlJ04-06 Manuel A. Quintana (PN) do. IlJ06-1O Jose Figueroa Alcorta (PN) Vice-President 1910-14 Roque Saenz Pena (PN) Elite co-option 1914--16 Victorino de la Plaza (PN) Vice-President 1916-22 Hipolito Yrigoyen (UCR) Election 1922-28 Marcelo Torcuato de Alv~ar Radical co-option: election (UCR) 1928--30 Hipolito Yrigoyen (UCR) Election 1930-32 Jose Felix Uriburu Military coup 1932-38 Agustin P. Justo (Can) Elite co-option 1938-40 Roberto M. Ortiz (Con) Elite co-option 1940-43 Ramon F. Castillo (Con) Vice-President: acting 1940- 42; then succeeded on resignation of President lune5-71943 Gen. Arturo P. Rawson Military coup 1943-44 Gen. Pedro P. Ramirez Military co-option 1944-46 Gen. Edelmiro J. Farrell Military co-option 1946-55 Col. Juan D. Peron Election 1955 Gen. Eduardo Lonardi Military coup 1955-58 Gen. Pedro Eugenio Military co-option Aramburu 1958--62 Arturo Frondizi (UCR-I) Election 1962--63 Jose Marfa Guido Military coup: President of Senate 1963--66 Dr Arturo IIIia (UCRP) Election 1966-70 Gen. Juan Carlos Onganfa Military coup June 8--14 1970 Adm. Pedro Gnavi Military coup 1970--71 Brig-Gen. Roberto M. Military co-option Levingston Mar22-241971 Junta Military co-option 1971-73 Gen. Alejandro Lanusse Military co-option 1973 Hector Campora (PJ) Election 1973-74 Lt-Gen. Juan D. Peron (PJ) Peronist co-option and election 1974--76 Marfa Estela (Isabel) Martinez Vice-President; death of de Peron (PJ) President Mar24--291976 Junta Military coup 1976-81 Gen. -

6 the International Dimensions of Democratization the Case of Argentina

Published in Nuno Severiano Teixeira (ed.): The International Politics of Democratization: Comparative perspectives. London and New York: Routledge, 2008. 6 The international dimensions of democratization The case of Argentina Andrés Malamud Introduction Argentine politics are usually described as eccentric, or at least unconventional, for a number of reasons. Economically, Argentina was a rich country that went from wealth to bankruptcy over a period of about 70 years, between 1930 and 2001. Socially, it has always had the most developed middle class and the most educated population in Latin America, a region where strong middle classes and universal education are extremely rare. Politically, it saw the emergence and predominance of rather autochthonous political movements, which included the most relevant and elusive example of Peronism. Internationally, it was the country in the Western Hemisphere that most frequently opposed American foreign policies apart from Cuba, although it never sided openly with either Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union. Argentina has been one of the most economically developed and one of the least politically stable countries in Latin America, a paradox first explained by Guillermo O’Donnell in the 1970s.1 In spite of all these particularities, the cycles of Argentine politics since 1930 can be matched with international developments taking place at the time. This chapter argues that both the frequent democratic breakdowns and processes of re- democratization that followed were linked to international factors. The chapter proceeds as follows. First, it describes the cycles of political instability in Argentina from 1930 to the present, tracing their relations with the international context. Second, it analyzes the democratization process that took place during the 1980s in order to single out the international factors that had an influence upon it. -

La Militarización Del Estado Durante La Última Dictadura Militar Argentina

57 La militarización del Estado durante la última dictadura militar argentina. Un estudio de los gabinetes del Poder Ejecutivo Nacional entre 1976 y 1983❧ Paula Canelo Universidad Nacional de San Martín, CONICET, Argentina doi:dx.doi.org/10.7440/histcrit62.2016.03 Artículo recibido: 27 de marzo de 2015/ Aprobado: 19 de agosto de 2015/ Modificado: 08 de septiembre de 2015 Resumen: Este artículo analiza el proceso de militarización del Estado llevado adelante por la última dictadura militar argentina, a través del estudio empírico de los perfiles de los ministros y de los ministerios que integraron los gabinetes del Poder Ejecutivo Nacional entre 1976 y 1983. Por un lado, se reconstruyen el perfil educativo, profesional y social de la élite ministerial, y la alta especialización que presentaron los “ministerios civiles” frente a los ocupados por las Fuerzas Armadas. Por otro lado, se analizan los determinantes del proceso de militarización: la desigual distribución del poder entre las tres Fuerzas Armadas, la importancia relativa de cada ministerio en la realización de los objetivos, tanto de la dictadura en general como de cada fuerza en particular, y la progresiva necesidad de ampliar los apoyos civiles. Finalmente, se identifica una “jerarquía ministerial” distintiva de esta dictadura, encabezada por los ministerios del Interior, de Trabajo y de Economía. Palabras clave: Fuerzas Armadas, dictadura, Gobierno, Estado, Argentina (Thesaurus); ministerios (palabras clave de autor). La militarización del Estado durante la última dictadura militar argentina. Un estudio de los gabinetes del Poder Ejecutivo Nacional entre 1976 y 1983 Abstract: This article analyzes the process of militarization of the state carried out by the last military dictatorship in Argentina, through an empirical study of the profiles of ministers and ministries that formed the National Executive Power cabinets between 1976 and 1983.