6 the International Dimensions of Democratization the Case of Argentina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring the Role of Epistemic Communities in Nuclear Non-Proliferation Outcomes

Politics & The Bomb: Exploring the Role of Epistemic Communities in Nuclear Non-Proliferation Outcomes. Sara Zahra Kutchesfahani UCL Department of Political Science Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science October 2010 DECLARATION I, Sara Zahra Kutchesfahani, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Sara Zahra Kutchesfahani ii ABSTRACT The role of epistemic communities in influencing policy formulation is underexplored in International Relations theory in general and in nuclear non-proliferation studies in particular. This thesis explores how epistemic communities – groups of experts knowledgeable in niche issue areas – have affected nuclear non-proliferation policy formulation in two important and under-studied cases: the Brazilian-Argentine Agency for Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials (ABACC) and the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) Program. It demonstrates that applying an epistemic community approach provides explanatory power heretofore lacking in explanations of these cases’ origins. The thesis applies the epistemic community framework to non-proliferation, using Haas’ (1992) seminal exploration of epistemic communities in the context of natural scientific and environmental policies. Specifically, it analyses the creation and successful implementation of ABACC and the CTR Program, which, respectively, verified the non-nuclear weapon status of Argentina and Brazil and facilitated the denuclearisation of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine. These cooperative nuclear non- proliferation agreements are shown to be the result of a process involving substantial input and direction from experts constituting epistemic communities. The thesis explores the differences in the emergence, composition, and influence mechanisms of the epistemic communities behind ABACC and the CTR Program. -

Engineering Growth: Innovative Capacity and Development in the Americas∗

Engineering Growth: Innovative Capacity and Development in the Americas∗ William F. Maloneyy Felipe Valencia Caicedoz July 1, 2016 Abstract This paper offers the first systematic historical evidence on the role of a central actor in modern growth theory- the engineer. We collect cross-country and state level data on the population share of engineers for the Americas, and county level data on engineering and patenting for the US during the Second Industrial Revolution. These are robustly correlated with income today after controlling for literacy, other types of higher order human capital (e.g. lawyers, physicians), demand side factors, and instrumenting engineering using the Land Grant Colleges program. We support these results with historical case studies from the US and Latin America. A one standard deviation increase in engineers in 1880 accounts for a 16% increase in US county income today, and patenting capacity contributes another 10%. Our estimates also help explain why countries with similar levels of income in 1900, but tenfold differences in engineers diverged in their growth trajectories over the next century. Keywords: Innovative Capacity, Human Capital, Engineers, Technology Diffusion, Patents, Growth, Development, History. JEL: O11,O30,N10,I23 ∗Corresponding author Email: [email protected]. We thank Ufuk Akcigit, David de la Croix, Leo Feler, Claudio Ferraz, Christian Fons-Rosen, Oded Galor, Steve Haber, Lakshmi Iyer, David Mayer- Foulkes, Stelios Michalopoulos, Guy Michaels, Petra Moser, Giacomo Ponzetto, Luis Serven, Andrei Shleifer, Moritz Shularick, Enrico Spolaore, Uwe Sunde, Bulent Unel, Nico Voigtl¨ander,Hans-Joachim Voth, Fabian Waldinger, David Weil and Gavin Wright for helpful discussions. We are grateful to William Kerr for making available the county level patent data. -

The 'Argentine Problem' : an Analysis of Political Instability in a Modern Society

THE 'ARGENTINE PROBLEM7: AN ANALYSIS OF POLITICAL INSTABILITY IN A MODERN SOCIETY Alphonse Victor Mallette B.A., University of Lethbridge, 1980 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS @ Alphonse Victor Mallette 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY June, 1986 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, proJect or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for flnanclal gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay Author: -. - rJ (date) -.-.--ABSTRACT This thesis is designed to explain, through political and historical analysis, a phenomenon identified by scholars of pol- itical development as the "Argentine Problem". Argentina is seen as a paradox, a nation which does not display the political stab- ility commensurate with its level of socio-economic development. The work also seeks to examine the origins and policies of the most serious manifestation of dictatorial rule in the nation's history, the period of military power from 1976 to 1983. -

The Transformation of Party-Union Linkages in Argentine Peronism, 1983–1999*

FROM LABOR POLITICS TO MACHINE POLITICS: The Transformation of Party-Union Linkages in Argentine Peronism, 1983–1999* Steven Levitsky Harvard University Abstract: The Argentine (Peronist) Justicialista Party (PJ)** underwent a far- reaching coalitional transformation during the 1980s and 1990s. Party reformers dismantled Peronism’s traditional mechanisms of labor participation, and clientelist networks replaced unions as the primary linkage to the working and lower classes. By the early 1990s, the PJ had transformed from a labor-dominated party into a machine party in which unions were relatively marginal actors. This process of de-unionization was critical to the PJ’s electoral and policy success during the presidency of Carlos Menem (1989–99). The erosion of union influ- ence facilitated efforts to attract middle-class votes and eliminated a key source of internal opposition to the government’s economic reforms. At the same time, the consolidation of clientelist networks helped the PJ maintain its traditional work- ing- and lower-class base in a context of economic crisis and neoliberal reform. This article argues that Peronism’s radical de-unionization was facilitated by the weakly institutionalized nature of its traditional party-union linkage. Although unions dominated the PJ in the early 1980s, the rules of the game governing their participation were always informal, fluid, and contested, leaving them vulner- able to internal changes in the distribution of power. Such a change occurred during the 1980s, when office-holding politicians used patronage resources to challenge labor’s privileged position in the party. When these politicians gained control of the party in 1987, Peronism’s weakly institutionalized mechanisms of union participation collapsed, paving the way for the consolidation of machine politics—and a steep decline in union influence—during the 1990s. -

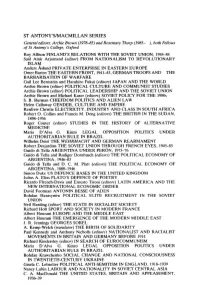

St Antony's/Macmillan Series

ST ANTONY'S/MACMILLAN SERIES General editors: Archie Brown (1978-85) and Rosemary Thorp (1985- ), both Fellows of St Antony's College, Oxford Roy Allison FINLAND'S RELATIONS WITH THE SOVIET UNION, 1944-84 Said Amir Arjomand (editor) FROM NATIONALISM TO REVOLUTIONARY ISLAM Anders Åslund PRIVATE ENTERPRISE IN EASTERN EUROPE Orner Bartov THE EASTERN FRONT, 1941-45, GERMAN TROOPS AND THE BARBARISATION OF WARFARE Gail Lee Bernstein and Haruhiro Fukui (editors) JAPAN AND THE WORLD Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL CULTURE AND COMMUNIST STUDIES Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND THE SOVIET UNION Archie Brown and Michael Kaser (editors) SOVIET POLICY FOR THE 1980s S. B. Burman CHIEFDOM POLITICS AND ALIEN LAW Helen Callaway GENDER, CULTURE AND EMPIRE Renfrew Christie ELECTRICITY, INDUSTRY AND CLASS IN SOUTH AFRICA Robert O. Collins and FrancisM. Deng (editors) THE BRITISH IN THE SUDAN, 1898-1956 Roger Couter (editor) STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE Maria D'Alva G. Kinzo LEGAL OPPOSITION POLITICS UNDER AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN BRAZIL Wilhelm Deist THE WEHRMACHT AND GERMAN REARMAMENT Robert Desjardins THE SOVIET UNION THROUGH FRENCH EYES, 1945-85 Guido di Tella ARGENTINA UNDER PERÓN, 1973-76 Guido di Tella and Rudiger Dornbusch (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1946-83 Guido di Tella and D. C. M. Platt (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1880-1946 Simon Duke US DEFENCE BASES IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Julius A. Elias PLATO'S DEFENCE OF POETRY Ricardo Ffrench-Davis and Ernesto Tironi (editors) LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC ORDER David Footman ANTONIN BESSE OF ADEN Bohdan Harasymiw POLITICAL ELITE RECRUITMENT IN THE SOVIET UNION Neil Harding (editor) THE STATE IN SOCIALIST SOCIETY Richard Holt SPORT AND SOCIETY IN MODERN FRANCE Albert Hourani EUROPE AND THE MIDDLE EAST Albert Hourani THE EMERGENCE OF THE MODERN MIDDLE EAST J. -

Argentine Government Embarrassed by Weapons Sale to Ecuador LADB Staff

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository NotiSur Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 3-31-1995 Argentine Government Embarrassed By Weapons Sale To Ecuador LADB Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur Recommended Citation LADB Staff. "Argentine Government Embarrassed By Weapons Sale To Ecuador." (1995). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur/ 11861 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NotiSur by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 56184 ISSN: 1060-4189 Argentine Government Embarrassed By Weapons Sale To Ecuador by LADB Staff Category/Department: Argentina Published: 1995-03-31 The alleged shipment of 75 tons of weapons from Argentina to Ecuador, apparently delivered during the five-week war between Ecuador and Peru, is proving to be an embarrassment to the government of President Carlos Saul Menem. On March 10, Menem ordered a thorough investigation into the circumstances surrounding the sale, but little progress has been made. Meanwhile, the opposition is calling for the resignation of those responsible, including Defense Minister Oscar Camilion. Argentina is one of the four guarantor countries along with the US, Chile, and Brazil of the 1942 Rio de Janeiro Protocol between Peru and Ecuador. When fighting broke out in a disputed area on the border between the two countries in January, the four guarantor countries worked diligently to broker a new peace agreement. The US declared an arms embargo against Peru and Ecuador on Feb. -

A R G E N T I

JUJUY PARAGUAY SALTA SOUTH FORMOSA Asunción PACIFIC TUCUMÁN CHACO SANTIAGO S OCEAN NE CATAMARCA SIO DEL ESTERO MI CORRIENTES á River an LA RIOJA Par BRAZIL SANTA FE SAN JUAN CÓRDOBA ENTRE RÍOS SAN LUIS URUGUAY MENDOZA Santiago Buenos Aires ARGENTINA Montevideo LA PAMPA BUENOS AIRES CHILE NEUQUÉN RÍO NEGRO SOUTH CHUBUT ATLANTIC OCEAN SANTA CRUZ Islas Malvinas TIERRA DEL FUEGO 0 200 miles david rock RACKING ARGENTINA opular protest erupted on the streets of Argentina through the hot December nights of 2001.1 Crowds from Pthe shanty towns attacked stores and supermarkets; banging their pots and pans, huge demonstrations of mainly middle- class women—cacerolazos—marched on the city centre; the piqueteros, organized groups of the unemployed, threw up road-blocks on high- ways and bridges. Twenty-seven demonstrators died, including five shot down by the police beneath the grand baroque façades of Buenos Aires’ Plaza de Mayo. The trigger for the fury had been the IMF’s suspension of loans to Argentina, on the grounds that President Fernando De la Rúa’s government had failed to meet its conditions on public-spending cuts. There was a run on the banks, as depositors rushed to get their money out and their pesos converted into dollars. De la Rúa’s Economy Minister Domingo Cavallo slapped on a corralito, a ‘little fence’, to limit the amount of cash that could be withdrawn—leaving many people’s savings trapped in failing banks. On December 20, as the protests inten- sified, De la Rúa resigned, his helicopter roaring up over the Rosada palace and the clouds of tear gas below. -

Según Lo Expuesto En Los Textos De Verónica Beyreuther Y Luis A

Según lo expuesto en los textos de Verónica El gobierno de la Revolución Libertadora se originó en un Beyreuther y Luis A. Romero, la llamada Revolución F golpe de Estado que terminó con el gobierno de Perón, Libertadora (1955-1958), debería ser considerada que había sido democráticamente electo. como parte de un régimen político semidemocrático. Luis A. Romero sostiene que en 1957 la Revolución Libertadora empezó a organizar su retiro y restablecer F La Libertadora había proscripto al peronismo la democracia con apoyo peronista Luis A. Romero sostiene que el poder del presidente Los votos eran prestados y las FFAA no confiaban en él V Arturo Frondizi (1958-1962) era precario por su acuerdo con Perón Al asumir la presidencia, el presidente Frondizi cumplió Frondizi sólo buscó obtener los votos que Perón podía el acuerdo que había hecho con Perón para conseguir F aportarle para ganar las elecciones. Una vez en el poder, su apoyo electoral no levantó las proscripciones como había prometido. Según Romero la política económica del gobierno de El gobierno de Illia puso especial énfasis en políticas Arturo Illia combinaba criterios básicos del populismo V económicas de redistribución y apoyo al mercado interno. reformista con elementos keynesianos. Según Luis A. Romero, el dominio de Vandor sobre sindicatos y organizaciones políticas peronistas lo llevó F Vandor pretendía institucionalizar al peronismo sin Perón. al sometimiento a Perón Según Luis A Romero el gobierno de la Revolución Argentina (1966-1973) se inició con un shock V Se disolvió el parlamento y los partidos políticos autoritario Según Luis Alberto Romero el Cordobazo (1969) fue Fue el episodio fundador de una ola de movilización social generador de cambios en la participación política y V y del nacimiento de un nuevo activismo sindical social Según Luis A. -

Working Paper 3

WORKING PAPER 3 The International Dimensions of Democratization: The Case of Argentina Andrés Malamud, Centro de Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia, Instituto de Ciências do Trabalho e da Empresa WORKING PAPER n.º 3 The International Dimensions of Democratization: The Case of Argentina Andrés Malamud Introduction Argentine politics are usually described as eccentric or, at least, unconventional. This is so for a number of reasons. From an economic perspective, Argentina was a rich country that went all the way from wealth to bankrupt in less than seventy years –between 1930 and 2001. From a social perspective, it has always had the most developed middle class and the most educated population in Latin America, a region where strong middle classes and universal education are extremely rare. From a political perspective, it saw the emergence and predominance of rather autochthonous political movements, which included Peronism as the most relevant and elusive example. From an international perspective, it was the country in the Western Hemisphere that most frequently opposed American foreign policies apart from Cuba –although it never sided openly with either Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union. Argentina was also the most economically developed and one of the least politically stable country in Latin America, a paradox that was first explained by O’Donnell in the 1970s (1973). In spite of all these particularities, the cycles of Argentine politics since 1930 can be matched with the international developments taking place at the time. This chapter argues that both the frequent democratic breakdowns and the processes of re-democratization that followed were linked to international factors, which were present as either causes or consequences or both of the domestic moves. -

Eonfi DENTIA~ AS AMENDED Tj..{ 61'21 , 9.OO'jt ~R/JLI'ja~ Bui~J Jdli~ IIRL COHFIDEN'fia1j -2

eOtifr' I DEN'l? IAL CONFIDENT/At 7663 THE WH ITE HOUSE WASHI NGTON MEMORANDUM OF CONVERSATION SUBJECT: Meeting with President Carlos Menem of Argentina PARTICIPANTS: The President Nicholas Brady, Secretary of the Treasury John H. Sununu, Chief of Staff Brent Scowcroft, Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs Lawrence Eagleburger, Deputy Secretary of State Robert M. Gates, Assistant to the President and Deputy for National Security Affairs David C. Mulford, Under Secretary of Treasury for International Affairs Terence Todman, Ambassador to Argentina Bernard Aronson, Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Everett Ellis Briggs, Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Latin America and the Caribbean Carlos Menem, President of Argentina Domingo Cavallo, Foreign Minister of Argentina Guido Di Tella, Argentine Ambassador to the United States Nestor Rapanelli, Minister of Economy of Argentina Alberto Kohan, Chief of Staff to President Menem Humberto Toledo, Spokesman for President Menem DATE, TIME September 27, 1989, 11:50 a.m.-12:40 p.m. EST AND PLACE: The Cabinet Room The President received President Menem at 11:40 a.m. in the Oval Office, after which the two stopped briefly at the edge of the Rose Garden for a friendly exchange with the media pool before going to the Residence to meet Mrs. Bush. They returned to the Cabinet Room at noon for the formal meeting. The President: I wanted to show President Menem the White House and introduce Mrs. Bush to him. And I wanted our press to see for themselves the affection we feel for this president and friend. -

HISTORIA SOCIAL DA ARGENTINA 08 05 V.9.Indd

Relações coleção coleção Internacionais História social da Argentina contemporânea MINISTÉRIO DAS RELAÇÕES EXTERIORES Ministro de Estado Aloysio Nunes Ferreira Secretário ‑Geral Embaixador Marcos Bezerra Abbott Galvão FUNDAÇÃO ALEXANDRE DE GUSMÃO Presidente Embaixador Sérgio Eduardo Moreira Lima Instituto de Pesquisa de Relações Internacionais Diretor Ministro Paulo Roberto de Almeida Centro de História e Documentação Diplomática Diretor Embaixador Gelson Fonseca Junior Conselho Editorial da Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão Presidente Embaixador Sérgio Eduardo Moreira Lima Membros Embaixador Ronaldo Mota Sardenberg Embaixador Jorio Dauster Magalhães Embaixador Gelson Fonseca Junior Embaixador José Estanislau do Amaral Souza Embaixador Eduardo Paes Saboia Ministro Paulo Roberto de Almeida Ministro Paulo Elias Martins de Moraes Professor Francisco Fernando Monteoliva Doratioto Professor José Flávio Sombra Saraiva Professor Eiiti Sato A Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão, instituída em 1971, é uma fundação pública vinculada ao Ministério das Relações Exteriores e tem a finalidade de levar à sociedade civil informações sobre a realidade internacional e sobre aspectos da pauta diplomática brasileira. Sua missão é promover a sensibilização da opinião pública para os temas de relações internacionais e para a política externa brasileira. Torcuato S. Di Tella História social da Argentina contemporânea 2ª Edição revisada Brasília – 2017 Direitos de publicação reservados à Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão Ministério das Relações Exteriores Esplanada dos Ministérios, Bloco H Anexo II, Térreo 70170 ‑900 Brasília–DF Telefones: (61) 2030‑6033/6034 Fax: (61) 2030 ‑9125 Site: www.funag.gov.br E ‑mail: [email protected] Equipe Técnica: Eliane Miranda Paiva André Luiz Ventura Ferreira Fernanda Antunes Siqueira Gabriela Del Rio de Rezende Luiz Antônio Gusmão Título original: Historia social de la Argentina contemporánea. -

La Descomposición Del Poder Militar En La Argentina. Las Fuerzas Armadas Durante Las Presidencias De Galtieri, Bignone Y Alfonsín (1981-1987)∗

La descomposición del poder militar en la Argentina. Las Fuerzas Armadas durante las presidencias de Galtieri, Bignone y Alfonsín (1981-1987)∗ Paula Canelo No existen en la historia de los hombres paréntesis inexplicables. Y es precisamente en los períodos de “excepción”, en esos momentos molestos y desagradables que las sociedades pretenden olvidar, colocar entre paréntesis, donde aparecen sin mediaciones ni atenuantes, los secretos y las vergüenzas del poder cotidiano. Pilar Calveiro (1998) Introducción La normalidad nada prueba, la excepción, todo. Es en los períodos de crisis de las pautas normales de desenvolvimiento de las sociedades donde es posible encontrar los fundamentos mismos de la normalidad; es allí, en los momentos donde el poder tambalea, donde se revelan los criterios “normales” del ejercicio del poder. La última dictadura militar, autodenominada “Proceso de Reorganización Nacional” constituyó, en efecto, un momento de excepción y de quiebre en el devenir histórico de la sociedad argentina. Durante su período de máximo poderío, el correspondiente a la primera presidencia del general Videla (1976-1978), el régimen logró concretar gran parte de sus objetivos refundacionales mediante la implementación del terrorismo estatal y de la política económica del ministro Martínez de Hoz. Sostenida por un férreo aislamiento de la misma sociedad sobre la que implementaba la política represiva más devastadora de la historia argentina, y cohesionada tras la construcción de un enemigo “subversivo” omnipresente, la alianza cívico-militar que llevó adelante el proyecto dictatorial avanzó significativamente en la desarticulación de la sociedad de posguerra. Sin embargo, lejos de conformar un todo monolítico, la contradictoria alianza entre militares y civiles liberales comenzó a demostrar síntomas de agotamiento a poco de andar.