Exploring the Role of Epistemic Communities in Nuclear Non-Proliferation Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palestra: Personalidades Políticas E Filatelia – Clube Filatélico Candidés

Palestra: Personalidades Políticas e Filatelia – Clube Filatélico Candidés Presidentes: Primeira República - (República Velha: República da Espada e República Oligárquica) (15/11/1889 a 24/10/1930 – 40 anos, 11 meses e 9 dias) Manuel Deodoro da Fonseca (Alagoas da Lagoa do Sul, 05/08/1827 — Rio de Janeiro, 23/08/1892): militar e político brasileiro, 1° presidente do Brasil e uma das figuras centrais da Proclamação da República no país. Período de mandato: 15/11/1889 a 23/11/1891. Vice-presidente: Nenhum (1889–1891) Floriano Peixoto (1891) Selos lançados: Série Alegorias Republicanas (1906 – 200 Réis), Série Alegorias Republicanas (1915 – 200 Réis), Série Heróis Nacionais (2008 – R$ 0,90). https://colnect.com/br/stamps/list/country/4226-Brasil/item_name/deodoro+da+fonseca Floriano Vieira Peixoto (Maceió, 30/04/1839 — Barra Mansa, 29/06/1895): militar e político brasileiro, primeiro vice-presidente e 2° presidente do Brasil, cujo governo abrange a maior parte do período da história brasileira conhecido como República da Espada. Período de mandato: 23/11/1891 a 15/11/1894 Vice-presidente: Cargo vago Selos lançados: Série Alegorias Republicanas (1906 – 300 Réis), Série Definitivos Milréis (Netinha) (1941 (2 selos - 5,000 Brasil Réis)), Série Definitos Cruzeiro (1946 – 5 Cruzeiros) https://colnect.com/br/stamps/list/country/4226-Brasil/item_name/floriano+peixoto/page/1 Prudente José de Moraes Barros (Itu, 04/10/1841 — Piracicaba, 03/12/1902): advogado e político brasileiro. Foi presidente do estado de São Paulo (cargo equivalente ao de governador), senador, presidente da Assembleia Nacional Constituinte de 1891 e 3° presidente do Brasil, tendo sido o 1° civil a assumir o cargo e o primeiro presidente por eleição direta. -

The Brazilian Naval Strategy and the Development of the Defense Logistics Base

THE BRAZILIAN NAVAL STRATEGY AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DEFENSE LOGISTICS BASE Eduardo Siqueira Brick1 Wilson Soares Ferreira Nogueira2 ABSTRACT This study aims to offer an interpretation of how the government’s priorities for national defense and the evolution of the Brazilian Naval Strategy (BNS) have influenced the development of the Defense Logistics Base (DLB) that supports the Brazilian Navy, from the country’s independence up to the present day. Then, it presents and develops the concept of DLB, discusses strategy concepts and its relation with defense policies, outlines how the organizational culture of the Navy has influenced decisions, and describes the evolution of the DLB of direct interest of the Naval Force, pari passu with the evolution of the BNS, highlighting external and internal influences it has received due to government changes and the introduction of the National Defense Strategy (NDS). Key words: Defense Logistics Base. National defense. Naval strategy. Brazilian Navy. 1 Doctor’s degree in Systems Engineering from US Naval Postgraduate School, United States (1976), Full Professor at Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niteroi, RJ, Brazil. E-mail: brick@produção.uff.br 2 Master’s degree in Naval Science from Escola de Guerra Naval (2004); Master’s degree in Strategic Studies of Defense and Security from Universidade Federal Fluminense (2014). E-mail: [email protected] R. Esc. Guerra Naval, Rio de Janeiro, v.23, n.1, p. 11 - 40. jan./apr. 2017 12 THE BRAZILIAN NAVAL STRATEGY AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DEFENSE LOGISTICS BASE INTRODUCTION For the realistic current of international relations, the States seek to ensure their own survival and sovereignty, and as they pursue this goal, they also seek to increase their relative powers. -

Páginas Iniciais.Indd

Sumário 3.11.1930 - 29.10.1945 Os Presidentes e a República Os Presidentes e a República Deodoro da Fonseca a Dilma Rousseff Deodoro da Fonseca Os Presidentes e a República Deodoro da Fonseca a Dilma Rousseff Rio de Janeiro - 2012 5ª edição Sumário 3.11.1930 - 29.10.1945 Os Presidentes e a República Getúlio Dornelles Vargas 3.11.1930 - 29.10.1945 Copyright © 2012 by Arquivo Nacional 1ª edição, 2001 - 2ª edição revista e ampliada, 2003 - 3ª edição revista, 2006 4ª edição revista e ampliada, 2009 - 5ª edição revista e ampliada, 2012 Praça da República, 173, 20211-350, Rio de Janeiro - RJ Telefone: (21) 2179-1253 Fotos da Capa: Palácio do Catete e Palácio do Planalto, 20 de abril de 1960. Arquivo Nacional Presidenta da República Dilma Rousseff Ministro da Justiça José Eduardo Cardozo Diretor-Geral do Arquivo Nacional Jaime Antunes da Silva Arquivo Nacional (Brasil) Os presidentes e a República: Deodoro da Fonseca a Dilma Rousseff / Arquivo Nacional. - 5ª ed. rev. e ampl. - Rio de Janeiro: O Arquivo, 2012. 248p. : il.;21cm. Inclui bibliografi a ISBN: 978-85-60207-38-1 (broch.) 1. Presidentes - Brasil - Biografi as. 2. Brasil - História - República, 1889. 3. Brasil - Política e Governo, 1889-2011. I.Título. CDD 923.1981 Sumário 3.11.1930 - 29.10.1945 Equipe Técnica do Arquivo Nacional Coordenadora-Geral de Acesso e Difusão Documental Maria Aparecida Silveira Torres Coordenadora de Pesquisa e Difusão do Acervo Maria Elizabeth Brêa Monteiro Redação de Textos e Pesquisa de Imagens Alba Gisele Gouget, Claudia Heynemann, Dilma Cabral e Vivien Ishaq Edição de Texto Alba Gisele Gouget, José Cláudio Mattar e Vivien Ishaq Revisão Alba Gisele Gouget e José Cláudio Mattar Projeto Gráfi co Giselle Teixeira Diagramação Tânia Bittencourt Para a elaboração do livro Os presidentes e a República, contamos com o apoio da Radiobrás na cessão das imagens relativas aos governos de Ernesto Geisel a Fernando Henrique Cardoso. -

The 'Argentine Problem' : an Analysis of Political Instability in a Modern Society

THE 'ARGENTINE PROBLEM7: AN ANALYSIS OF POLITICAL INSTABILITY IN A MODERN SOCIETY Alphonse Victor Mallette B.A., University of Lethbridge, 1980 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS @ Alphonse Victor Mallette 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY June, 1986 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, proJect or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for flnanclal gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay Author: -. - rJ (date) -.-.--ABSTRACT This thesis is designed to explain, through political and historical analysis, a phenomenon identified by scholars of pol- itical development as the "Argentine Problem". Argentina is seen as a paradox, a nation which does not display the political stab- ility commensurate with its level of socio-economic development. The work also seeks to examine the origins and policies of the most serious manifestation of dictatorial rule in the nation's history, the period of military power from 1976 to 1983. -

St Antony's/Macmillan Series

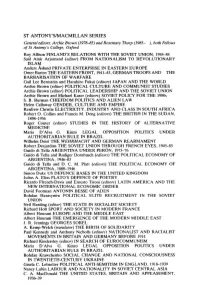

ST ANTONY'S/MACMILLAN SERIES General editors: Archie Brown (1978-85) and Rosemary Thorp (1985- ), both Fellows of St Antony's College, Oxford Roy Allison FINLAND'S RELATIONS WITH THE SOVIET UNION, 1944-84 Said Amir Arjomand (editor) FROM NATIONALISM TO REVOLUTIONARY ISLAM Anders Åslund PRIVATE ENTERPRISE IN EASTERN EUROPE Orner Bartov THE EASTERN FRONT, 1941-45, GERMAN TROOPS AND THE BARBARISATION OF WARFARE Gail Lee Bernstein and Haruhiro Fukui (editors) JAPAN AND THE WORLD Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL CULTURE AND COMMUNIST STUDIES Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND THE SOVIET UNION Archie Brown and Michael Kaser (editors) SOVIET POLICY FOR THE 1980s S. B. Burman CHIEFDOM POLITICS AND ALIEN LAW Helen Callaway GENDER, CULTURE AND EMPIRE Renfrew Christie ELECTRICITY, INDUSTRY AND CLASS IN SOUTH AFRICA Robert O. Collins and FrancisM. Deng (editors) THE BRITISH IN THE SUDAN, 1898-1956 Roger Couter (editor) STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE Maria D'Alva G. Kinzo LEGAL OPPOSITION POLITICS UNDER AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN BRAZIL Wilhelm Deist THE WEHRMACHT AND GERMAN REARMAMENT Robert Desjardins THE SOVIET UNION THROUGH FRENCH EYES, 1945-85 Guido di Tella ARGENTINA UNDER PERÓN, 1973-76 Guido di Tella and Rudiger Dornbusch (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1946-83 Guido di Tella and D. C. M. Platt (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1880-1946 Simon Duke US DEFENCE BASES IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Julius A. Elias PLATO'S DEFENCE OF POETRY Ricardo Ffrench-Davis and Ernesto Tironi (editors) LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC ORDER David Footman ANTONIN BESSE OF ADEN Bohdan Harasymiw POLITICAL ELITE RECRUITMENT IN THE SOVIET UNION Neil Harding (editor) THE STATE IN SOCIALIST SOCIETY Richard Holt SPORT AND SOCIETY IN MODERN FRANCE Albert Hourani EUROPE AND THE MIDDLE EAST Albert Hourani THE EMERGENCE OF THE MODERN MIDDLE EAST J. -

Según Lo Expuesto En Los Textos De Verónica Beyreuther Y Luis A

Según lo expuesto en los textos de Verónica El gobierno de la Revolución Libertadora se originó en un Beyreuther y Luis A. Romero, la llamada Revolución F golpe de Estado que terminó con el gobierno de Perón, Libertadora (1955-1958), debería ser considerada que había sido democráticamente electo. como parte de un régimen político semidemocrático. Luis A. Romero sostiene que en 1957 la Revolución Libertadora empezó a organizar su retiro y restablecer F La Libertadora había proscripto al peronismo la democracia con apoyo peronista Luis A. Romero sostiene que el poder del presidente Los votos eran prestados y las FFAA no confiaban en él V Arturo Frondizi (1958-1962) era precario por su acuerdo con Perón Al asumir la presidencia, el presidente Frondizi cumplió Frondizi sólo buscó obtener los votos que Perón podía el acuerdo que había hecho con Perón para conseguir F aportarle para ganar las elecciones. Una vez en el poder, su apoyo electoral no levantó las proscripciones como había prometido. Según Romero la política económica del gobierno de El gobierno de Illia puso especial énfasis en políticas Arturo Illia combinaba criterios básicos del populismo V económicas de redistribución y apoyo al mercado interno. reformista con elementos keynesianos. Según Luis A. Romero, el dominio de Vandor sobre sindicatos y organizaciones políticas peronistas lo llevó F Vandor pretendía institucionalizar al peronismo sin Perón. al sometimiento a Perón Según Luis A Romero el gobierno de la Revolución Argentina (1966-1973) se inició con un shock V Se disolvió el parlamento y los partidos políticos autoritario Según Luis Alberto Romero el Cordobazo (1969) fue Fue el episodio fundador de una ola de movilización social generador de cambios en la participación política y V y del nacimiento de un nuevo activismo sindical social Según Luis A. -

Anais Do Senado

SENADO FEDERAL ANAIS DO SENADO ANO DE 1972 LIVRO 3 Secretaria Especial de Editoração e Publicações - Subsecretaria de Anais do Senado Federal TRANSCRIÇÃO 23ª SESSÃO DA 2ª SESSÃO LEGISLATIVA DA 7ª LEGISLATURA, EM 2 DE MAIO DE 1972 PRESIDÊNCIA DOS SRS. PETRÔNIO PORTELLA, CARLOS LINDENBERG RUY CARNEIRO E GUIDO MONDIN Às 14 horas e 30 minutos, acham-se, O SR. PRESIDENTE (Petrônio Portella): – O presentes os Srs. Senadores: Expediente que acaba de ser lido irá à publicação. Adalberto Sena Geraldo Mesquita – José (Pausa.) Lindoso – José Esteves – Cattete Pinheiro – Renato Há oradores inscritos. Franco – Alexandre Costa – Clodomir Milet – Concedo a palavra ao nobre Líder Nelson Petrônio Portella – Helvídio Nunes – Waldemar Carneiro, que falará nesta qualidade. Alcântara – Wilson Gonçalves – Dinarte Mariz – João O SR. NELSON CARNEIRO (como Líder. Cleofas – Wilson Campos – Teotônio Vilela – Sem revisão do orador.): – Sr. Presidente, antes de Augusto Franco – Leandro Maciel – Lourival Baptista ler a breve oração que havia, redigido sobre o – Antônio Fernandes – Heitor Dias – Ruy Santos – problema do menor abandonado, desejo dirigir um Carlos Lindenberg – Eurico Rezende – João Calmon apelo ao Senhor Presidente da República. – Paulo Torres – Vasconcelos Torres – Benjamin Acabo de visitar a zona cacaueira. Encontrei Farah – Nelson Carneiro – José Augusto – Orlando ali a angústia eo desespero. Vários cacauicultores, Zancaner – Benedito Ferreira – Emival Caiado – de longos anos de atividade naquela lavoura, estão Osires Teixeira – Filinto Müller – Saldanha Derzi – sendo acionados. E o Senhor Presidente da Mattos Leão – Daniel Krieger – Guido Mondin – República declarou que ninguém perderia suas Tarso Dutra. fazendas. O SR. PRESIDENTE (Petrônio Portella): – A Sr. Presidente, trarei dados mais completos lista de presença acusa o comparecimento de 40 em outra oportunidade, mas, neste ensejo, queria Srs. -

The Armed Forces in Brazilian's Constitutions1

Rev. bras. Ci. Soc. vol.5 no.se São Paulo 2011 The Armed Forces in Brazilian’s Constitutions1 Autonomia na lei: as forças armadas nas constituições nacionais Autonomie dans la loi: l'armée dans les constitutions nationales Suzeley Mathias; Andre Guzzi ABSTRACT This article discusses the differences between the function, the mission and the role of the Armed Forces across the different Brazilian Constitutions: from the “Imperial Constitution” of 1824 to the so- called “Citizen Constitution” of 1988. The hypothesis presented here is that military autonomy has been maintained by law, which makes it difficult to promote the military subordination necessary to consolidate Brazil's democratic regime. Keywords: Brazil, Legislation, Armed Forces, Constitution, Autonomy, Democracy. RESUMO O objetivo do presente trabalho é analisar as diferenças entre função, missão e papel das Forças Armadas nas Cartas Constitucionais brasileiras, de 1824 a 1988. A hipótese discutida é que a disjunção consagrada constitucionalmente entre Lei e Ordem consolida uma limitação à democracia ao autorizar intervenções das Forças Armadas para além da Lei. Argumentamos que a autonomia militar, garantida pelas Cartas, dificulta sobremaneira a subordinação militar em relação ao poder civil, necessária à consolidação do regime democrático. Palavras-chave: Legislação; Forças Armadas; Constituição; Autonomia; Democracia. 1 A primary version of this paper was published in 1991 in a no-longer-existent Brazilian journal called Política e Estratégia (Politics and Strategy). RESUMÉ L'objectif de ce travail est d'analyser les différences entre la fonction, la mission et le rôle de l'Armée dans les constitutions brésiliennes, de 1824 à 1988. L'hypothèse en discussion est que la disjonction consacrée constitutionnellement entre la Loi et l'Ordre consolide une limitation à la démocratie en autorisant des interventions dans l'Armée qui vont au-delà de la Loi. -

DITADURA MILITAR (1964 - 1985) Aulas 27 E 28 03/1964 – 04/1964 RANIERI MAZZILI ALTO COMANDO REVOLUCIONÁRIO

DITADURA MILITAR (1964 - 1985) Aulas 27 e 28 03/1964 – 04/1964 RANIERI MAZZILI ALTO COMANDO REVOLUCIONÁRIO Período de centralização político-administrativa Integrantes: . General Arthur da Costa e Silva . Brigadeiro Correia de Mello . Almirante Augusto Rademaker Novas eleições deveriam ser feitas em 30 dias ATO INSTITUCIONAL Nº 1 (AI-1) Militares ativos poderiam ser eleitos O direito de votar e ser votado poderia ser suspenso pelo Alto Comando Revolucionário Mandatos poderia ser cassados sem precisar de aprovação do jurídico Presidente teria poderes especiais (como para decretar estado de sítio sem precisar de aprovação) O próximo presidente seria votado pelo Congresso Nacional 1964 – 1967 CASTELLO BRANCO VICE: JOSÉ MARIA ALKMIN Inicia-se a repressão Período de dificuldades políticas em meio a oposição de ideias dentro das Forças Armadas As cassações de mandatos e as suspensões de direitos políticos começam UNE (União Nacional dos Estudantes) é extinta Existência de intervenção federal nos estados que apresentavam resistência 1964 – 1967 CASTELLO BRANCO VICE: JOSÉ MARIA ALKMIN Questão da sucessão PRESIDENCIAL . Eleições deveriam ser feitas ao fim de 1965 (Castello Branco, pela Constituição, só estaria completando o governo Jango) . JK e Carlos Lacerda eram possíveis candidatos (JK seria o possível eleito) . Os militares se posicionam contra a candidatura de JK e as eleições . JK resistiu, mas teve seu mandato e direitos políticos suspensos por 10 anos . É prorrogado o governo de Castello Branco 1964 – 1967 CASTELLO BRANCO VICE: JOSÉ MARIA ALKMIN Questão da sucessão ESTADUAL . Eleições deveriam ser feitas para os cargos de governadores estaduais . Após as eleições, percebeu-se que a oposição havia vencido em alguns estados importantes: MG, SC, MT e Guanabara ATO INSTITUCIONAL Nº 2 (AI-2) O Presidente da República seria eleito indiretamente Extinção dos partidos políticos Regulamentação nova para organização partidária 1964 – 1967 CASTELLO BRANCO VICE: JOSÉ MARIA ALKMIN Algumas organizações conseguiram se adequar: . -

La Descomposición Del Poder Militar En La Argentina. Las Fuerzas Armadas Durante Las Presidencias De Galtieri, Bignone Y Alfonsín (1981-1987)∗

La descomposición del poder militar en la Argentina. Las Fuerzas Armadas durante las presidencias de Galtieri, Bignone y Alfonsín (1981-1987)∗ Paula Canelo No existen en la historia de los hombres paréntesis inexplicables. Y es precisamente en los períodos de “excepción”, en esos momentos molestos y desagradables que las sociedades pretenden olvidar, colocar entre paréntesis, donde aparecen sin mediaciones ni atenuantes, los secretos y las vergüenzas del poder cotidiano. Pilar Calveiro (1998) Introducción La normalidad nada prueba, la excepción, todo. Es en los períodos de crisis de las pautas normales de desenvolvimiento de las sociedades donde es posible encontrar los fundamentos mismos de la normalidad; es allí, en los momentos donde el poder tambalea, donde se revelan los criterios “normales” del ejercicio del poder. La última dictadura militar, autodenominada “Proceso de Reorganización Nacional” constituyó, en efecto, un momento de excepción y de quiebre en el devenir histórico de la sociedad argentina. Durante su período de máximo poderío, el correspondiente a la primera presidencia del general Videla (1976-1978), el régimen logró concretar gran parte de sus objetivos refundacionales mediante la implementación del terrorismo estatal y de la política económica del ministro Martínez de Hoz. Sostenida por un férreo aislamiento de la misma sociedad sobre la que implementaba la política represiva más devastadora de la historia argentina, y cohesionada tras la construcción de un enemigo “subversivo” omnipresente, la alianza cívico-militar que llevó adelante el proyecto dictatorial avanzó significativamente en la desarticulación de la sociedad de posguerra. Sin embargo, lejos de conformar un todo monolítico, la contradictoria alianza entre militares y civiles liberales comenzó a demostrar síntomas de agotamiento a poco de andar. -

Ernani Do Amaral Peixoto

PEIXOTO, Ernani do Amaral *militar; interv. RJ 1937-1945; const. 1946; dep. fed. RJ 1946-1951; gov. RJ 1951- 1955; emb. Bras. EUA 1956-1959; min. Viação 1959-1961; min. TCU 1961-1962; min. Extraord. Ref. Admin. 1963; dep. fed. RJ 1963-1971; sen. RJ 1971-1987. Ernâni Amaral Peixoto nasceu no Rio de Janeiro, então Distrito Federal, em 14 de julho de 1905, filho de Augusto Amaral Peixoto e de Alice Monteiro Amaral Peixoto. Seu pai combateu a Revolta da Armada — levante de oposição ao presidente Floriano Peixoto que envolveu a esquadra fundeada na baía de Guanabara de setembro de 1893 a março de 1894 sob a chefia do almirante Custódio de Melo e mais tarde do almirante Luís Filipe Saldanha da Gama —, atuando no serviço médico da Brigada Policial do Rio de Janeiro. Dedicando-se depois à clínica médica, empregou em seu consultório o então acadêmico Pedro Ernesto Batista, vindo mais tarde a trabalhar na casa de saúde construída por este. Quando Pedro Ernesto se tornou prefeito do Distrito Federal, foi seu chefe de gabinete, chegando a substituí-lo interinamente entre 1934 e 1935. Seu avô paterno, comerciante de café, foi presidente da Câmara Municipal de Parati (RJ). Seu avô do lado materno, comerciante e empreiteiro de obras públicas arruinado com a reforma econômica de Rui Barbosa — que desencadeou o chamado “encilhamento”, política caracterizada por grande especulação financeira e criação de inúmeras empresas fictícias —, alcançou o cargo de diretor de câmbio do Banco do Brasil na gestão de João Alfredo Correia de Oliveira (1911-1914). Seu irmão, Augusto Amaral Peixoto Júnior, foi revolucionário em 1924 e 1930, constituinte em 1934 e deputado federal pelo Distrito Federal de 1935 a 1937 e de 1953 a 1955. -

La Argentina

LA ARGENTINA NAME: República Argentina POPULATION: 43,350,000 ETHNIC GROUPS: White (97%; Spanish and Italian mostly); Mestizo (2%); Amerindian (1%) La Argentina —1— CAPITAL: Buenos Aires (13,500,000) Other cities: Córdoba (1,500,000); Rosario (1,200,000) LANGUAGES: Spanish (official) RELIGION: Roman Catholic (90%) LIFE EXPECTANCY: Men (68); women (75) LITERACY: 97% GOVERNMENT: Democratic republic President: Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (since May 2007) MILITARY: 67,300 active troops ECONOMY: food processing (meat), autos, chemicals, grains, crude oil MONEY: peso (1.0 = $1.00 US) GEOGRAPHY: Atlantic coast down to tip of South America; second largest country in South America; Andean mountains on west; Aconcagua, highest peak in S. America (22,834 ft.); Pampas in center; Gran Chaco in north; Río de la Plata estuary (mostly fresh water from Paraná and Uruguay Rivers) HISTORY: Prehistory Nomadic Amerindians (hunter gatherers); most died by 19th century 1516 Juan de Solís discovered Argentina and claimed it for Spain 1536 Buenos Aires founded by Pedro de Mendoza; 1580 Buenos Aires refounded by Juan de Garay 1776 Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata created (Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia). 1778-1850 José de San Martín, born in Buenos Aires, liberator of cono sur; criollo (Spanish military father) raised in Spain. 1805-1851 Esteban Echeverría (writer): father of Latin American romanticism; author of El matadero (essay against Rosas). 1806 Great Britain‟s forces occupy port of Buenos Aires demanding free trade; porteños expel English troops; criollo porteños gain self- confidence. 1810 (May 25) A cabildo abierto of criollos assumes power for Fernando VII; cabildo divided between unitarios (liberals for centralized power) and federalistas (conservatives for federated republic with power in provinces).