The Czechoslovak Exiles and Anti-Semitism in Occupied Europe During the Second World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Threshold of the Holocaust: Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms In

Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. of the Holocaust carried out by the local population. Who took part in these excesses, and what was their attitude towards the Germans? The Author Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms Were they guided or spontaneous? What Tomasz Szarota is Professor at the Insti- part did the Germans play in these events tute of History of the Polish Academy in Occupied Europe and how did they manipulate them for of Sciences and serves on the Advisory their own benefit? Delving into the source Board of the Museum of the Second Warsaw – Paris – The Hague – material for Warsaw, Paris, The Hague, World War in Gda´nsk. His special interest Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Kaunas, this comprises WWII, Nazi-occupied Poland, Amsterdam – Antwerp – Kaunas study is the first to take a comparative the resistance movement, and life in look at these questions. Looking closely Warsaw and other European cities under at events many would like to forget, the the German occupation. On the the Threshold of Holocaust ISBN 978-3-631-64048-7 GEP 11_264048_Szarota_AK_A5HC PLE edition new.indd 1 31.08.15 10:52 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. -

En Irak 07.Qxd

THE CZECH REPUBLIC AND THE IRAQ CRISIS: SHAPING THE CZECH STANCE David Kr·l, Luk·ö Pachta Europeum Institute for European Policy, January 2005 Table of contens Executive Summary. 5 1. Introduction . 7 2. The President 1. Constitutional framework . 11 2. Havel versus Klaus . 13 3. The Presidentís position on the Iraq crisis . 15 3. The Government 1. Constitutional framework . 21 2. Governmental resolution: articulation of the Czech position. 22 3. Continuity of foreign policy ñ the Czech Republic and the ëcoalition of the willingí. 23 4. Political constellation within government . 26 5. Proposal of the Foreign Ministry . 27 6. Acceptance of the governmental position . 29 7. The power of personalities . 30 4. The Parliament 1. General framework. 35 2. Debate and role of the Parliament before the initiation of the Iraqi operation . 36 3. The Chamber of Deputies ñ critique by the opposition . 38 4. The Senate debate ñ lower influence of the political parties, higher influence of personalities . 39 5. Parliamentary discussion during the Iraq crisis. 42 6. Discussion on the dispatching of a field hospital to Basra . 43 5. The Political Parties 1. Czech Social Democratic Party (»SSD): Ambivalent workhorse of the Czech government . 50 2. Antiwar resolution of the »SSD Congress: A blow for the »SSD in government. 51 3. Smaller coalition parties: pro-American but constructive and loyal . 54 4. Civic Democratic Party (ODS): Clear position, weak critique of the government and conflict with Klaus . 55 5. Communist party (KS»M): Weak in influence but strong in rhetoric . 57 6. Conclusion . 59 7. Annexes. (in Czech version only) 3 Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY David Kr·l has been the chairman of EUROPEUM Institute for European Policy since ■ The Czech government expressed political support for the general objectives of 2000 where he also serves as the director of EU policies programme. -

Operation “Tomis III” and Ideological Diversion. Václav Havel in The

Promising young playwright Václav Havel in Schiller-Theater-Werkstatt, West Berlin, 1968 60Photo: Czech News Agency (ČTK) articles and studies Operation “Tomis III” and Ideological Diversion VÁCLAV HAVEL IN THE DOCUMENTS OF THE STATE SECURITY, 1965–1968 PAVEL žÁČEK Václav Havel attracted the interest of the State Security (StB) at the age of 28 at the latest, remaining in their sights until the end of the existence of the Communist totalitarian regime in Czechoslovakia. The first phase of his “targeting”, which ran until March 1968 and was organised by the 6th department of the (culture) II/A section of the Regional Directorate of the Ministry of the Interior (National Security Corps) in Prague, under the codename “Tomis III”, is particularly richly documented. This makes it possible to reconstruct the efforts of the pillars of power to keep the regime going in the period of social crisis before the Prague Spring. Analysis of the file agenda and other archive materials allow us to cast light on the circumstances of the creation of a “candidate agent” file on Havel, which occurred at the start of August 1965, evidently as the result of poor coordination of individual StB headquarters – and which 20 years ago became the subject of media controversy.1 First interest national economy […] GROSSMAN deliv- perfect fascism, and all those present In the agent report of collaborator ered a matching analysis of the situa- chimed in. […] The Source said that “Mirek” (Pavel Vačkář, b. 1940)2 of 24 tion, explained the emergence of liberal- he had met nobody at na Zábradlí who June 1964, the superintendent of the ism after “Stalin’s fall”, and spoke about was at least loyal to the government, 6th department of the (culture) II/A sec- a revolt by artists against rigid and non- either among the friends that visited tion of the Regional Directorate of sensical Socialist Realism […] Havel lat- the theatre or actors and staff them- the Ministry of the Interior (KS-MV), er described with a smile preparations selves… Capt. -

Introduction 1. Samuel P. Huntington, “Civilian Control of the Military: A

Notes Introduction 1. Samuel P. Huntington, “Civilian Control of the Military: A Theoretical State- ment,” in Political Behavior: A Reader in Theory and Research, ed. Heinz Eulau, Samuel J. Eldersveld, and Morris Janowitz (Glencoe: Free Press, 1956), 380. Among those in agreement with Huntington are S. E. Finer, The Man on Horseback: The Role of the Military in Politics (New York: Praeger, 1962); Bengt Abrahamsson, Military Pro- fessionalization and Political Power (Beverly Hills: Sage, 1972); Claude E. Welch Jr., Civilian Control of the Military (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1976); Amos Perlmutter, The Military and Politics in Modern Times (New Haven: Yale Uni- versity Press, 1977), and in The Political Influence of the Military (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980). Chapter 1 1. Samuel P. Huntington, The Soldier and the State (Cambridge: Harvard Univer- sity Press, 1957), 3. 2. Samuel P. Huntington, “Civilian Control of the Military: A Theoretical State- ment,” in Heinz Eulau, Samuel J. Eldersveld, and Morris Janowitz, eds., Political Be- havior: A Reader in Theory and Research (Glencoe: Free Press, 1956), 380. 3. Among those in agreement with Huntington are S. E. Finer, The Man on Horse- back: The Role of the Military in Politics (New York: Praeger, 1962); Bengt Abrahams- son, Military Professionalization and Political Power (Beverly Hills: Sage, 1972); Claude E. Welch Jr., Civilian Control of the Military (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1976); Amos Perlmutter, The Military and Politics in Modern Times (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977), and in The Political Influence of the Military (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980). -

Ivo PEJČOCH, Fašismus V Českých Zemích. Fašistické A

CENTRAL EUROPEAN PAPERS 2014 / II / 1 203 Ivo PEJČOCH Fašismus v českých zemích. Fašistické a nacionálněsocialistické strany a hnutí v Čechách a na Moravě 1922–1945 Praha: Academia 2011, 864 pages ISBN 978-80-200-1919-6 Critical review of Ivo Pejčoch’s book “Fascism in Czech countries. Fascist and national-so- cialist parties and movements in Bohemia and Moravia 1922-1945” The peer reviewed book written by Ivo Pejčoch, a historian working in the Military Historical Institute, was published by the Academia publishing house in 2011. The central topic of the monograph is, as the name suggests, mapping of the Czech fascism from the time of its origination in early 1920s through the period of Munich agreement and World War II to the year 1945. As the author mentions in preface, he restricts himself to the activity of organizations of Czech nation and language, due to extent limitation. The topic of the book picks up the threads of the earlier published monographs by Tomáš Pasák and Milan Nakonečný. But unlike Pasák’s book “Czech fascism 1922-1945 and col- laboration”, Ivo Pejčoch does not analyze fascism and seek causes of sympathies of a num- ber of important personalities to that ideology. On the contrary, his book rather presents a summary of parties, small parties and movements related to fascism and National Social- ism. He deals in more detail with the major ones - i.e. the Národní obec fašistická (National Fascist Community) or Vlajka (The Flag), but also for example the Kuratorium pro výchovu mládeže (Board for Youth Education) that was not a political party but, under the guid- ance of Emanuel Moravec, aimed at spreading the Roman-Empire ideas and influencing a large group of primarily young Protectorate inhabitants. -

Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938–1948

21 Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938 –1948 LUCIE ZADRAILOVÁ AND MILAN PECH 332 Lucie Zadražilová and Milan Pech Lucie Zadražilová (Skřivánková) is a curator at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, while Milan Pech is a researcher at the Institute of Christian Art at Charles University in Prague. Teir text is a detailed archival study of the activities of two Czech art institutions, the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague and the Mánes Association of Fine Artists, during the Nazi Protectorate era and its immediate aftermath. Te larger aim is to reveal that Czech cultural life was hardly dormant during the Protectorate, and to trace how Czech institutions negotiated the limitations, dangers, and interferences presented by the occupation. Te Museum of Decorative Arts cautiously continued its independent activities and provided otherwise unattainable artistic information by keeping its library open. Te Mánes Association of Fine Artists trod a similarly-careful path of independence, managing to avoid hosting exhibitions by representatives of Fascism and surreptitiously presenting modern art under the cover of traditionally- themed exhibitions. Tis essay frst appeared in the collection Konec avantgardy? Od Mnichovské dohody ke komunistickému převratu (End of the Avant-Garde? From the Munich Agreement to the Communist Takeover) in 2011.1 (JO) Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938–1948 In the light of new information gained from archival sources and contemporaneous documents it is becoming ever clearer that the years of the Protectorate were far from a time of cultural vacuum. Credit for this is due to, among other things, the endeavours of many people to maintain at least a partial continuity in public services and to achieve as much as possible within the framework of the rules set by the Nazi occupiers. -

GIPE-011912-05.Pdf

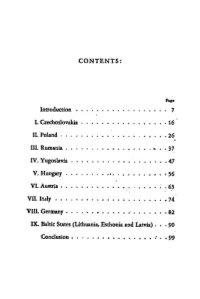

CONTENTS: Paco Introduction • • . 7 L Czechoslovakia . .J6 II. Poland .. • • 26 III. Rumania . ... • 37 IV. Yugoslavia . • • • •••• 47 V. Hungary ..• • • "'.. • "' • • • • . • , " l 56 VL Austtia ••. • • • • • ; • 6_5 VII. Italy ••• • ••• 74 VIII. Germany ••.•• •· • • • • 82 IX. Baltic States (Lithuania, Esthonia and latvia) . • • 90 Conclusion • • · . • • • • • • • , • • • • : • • 99 THE MILITARY J.MPORTANCE OF. CZECHOSLOVAKIA .IN EUROPE THE MILITARY IMPORTANCE OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA IN EUROPE COLONEL EMANUEL MORAVEC Profusor of tAe HigA Sclaool of War WitL. 8 Maps t 9 s a "Orl:.is" Printing and Pul:.lisl:.iog Co., Pregue l'BilfTBD BY «OABIB# l'B.A.GVlll li:II CZJtCHOBLOVA:&:IA. "If suc(.II!SS be achieved in uniting Austria with Germany, the collapse of Czechoslovakia will follow; Germany will then have common frontiers with Italy and Yugoslavia, and Italy will be strengthened against France." Ewald Banse in "Raum und Volk im Welt kriege", Edition of 1932. I BRIEF HISTORICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL OUTLINE The Rise of the Czechoslovak State After the defeat of the Central Powers at the end of October 1918 the Austro-Hungarian Empire fell asunder. The nations that had composed it either joined their kinsmen among the victorious Allied countries-Italy, Rumania and Yugoslavia--or formed new States. In this latter ma:nner arose Czechoslo vakia and Poland. Finally, there remained the racial· remnants of the old Monarchy-Austria with a Ger man population, and Hungary with a Magyar popu lation. The territories of the new Austria and Hun gary formed a central nationality zone in Central Europe touching the Italians on the West and the Ru manians on the East. North of this German-Magyar zone were the Slavonic nations forming the Republics· of Czechoslovakia and Poland. -

Democratizing Communist Militaries

Democratizing Communist Militaries Democratizing Communist Militaries The Cases of the Czech and Russian Armed Forces Marybeth Peterson Ulrich Ann Arbor To Mark, Erin, and Benjamin Copyright © by the University of Michigan 1999 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America V∞ Printed on acid-free paper 2002 2001 2000 1999 4 3 2 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ulrich, Marybeth Peterson. Democratizing Communist militaries : the cases of the Czech and Russian armed forces / Marybeth Peterson Ulrich. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-472-10969-3 (acid-free paper) 1. Civil-military relations—Russia (Federation) 2. Civil-military relations—Former Soviet republics. 3. Civil-military relations—Czech Republic. 4. Russia (Federation)—Armed Forces—Political activity. 5. Former Soviet republics—Armed Forces—Political activity. 6. Czech Republic—Armed Forces—Political activity. 7. Military assistance, American—Russia (Federation) 8. Military assistance, American—Former Soviet republics. 9. Military assistance, American—Czech Republic. I. Title. JN6520.C58 U45 1999 3229.5909437109049—dc21 99-6461 CIP Contents List of Tables vii Acknowledgments ix List of Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1. A Theory of Democratic Civil-Military Relations in Postcommunist States 5 Chapter 2. A Survey of Overall U.S. -

Pavel Tigrid

PAVEL TIGRID “Pavel Tigrid was a person that united – in a particular way – principles with politeness, decency, open-mindedness, and a sincere interest in the opinions of the other. I feel that Pavel Tigrid goes on living not only as a name, idea, and a principle, but also as a challenge – a challenge for all of us to try to combine open-mindedness, curiosity, decency, and a gentleman’s manners with principles.” Václav Havel Pavel Tigrid, born Pavel Schönfeld, was a Czech opinion journalist, writer, and politician. He was born on 27th October 1917 in Prague into a Jewish family. His father baptised him as a Catholic. The family roots of Pavel Schönfeld were linked to writers Antal Stašek and Ivan Olbracht. He attended a grammar school in Prague, and studied at the Faculty of Law at Charles University. During his studies, he started to be interested in journalism, publishing his first articles in the Student’s Magazine. The First Exile In March 1939, Tigrid went into exile for the first time – to London. At the beginning, he lived by manual work, being a warehouseman and a waiter; from 1940, he worked as a BBC broadcaster, and, later, as an editor of Voice of Free Czechoslovakia, a radio programme of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile. As editors were required to get pseudonyms – in order for their Protectorate relatives to remain safe – he changed his surname to Tigrid. He got inspired by the memory of his school years, when he distorted the name of the Tigris River into Tigrid. After the war, he had the surname confirmed officially. -

Buddhism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search

Buddhism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A statue of Gautama Buddha in Bodhgaya, India. Bodhgaya is traditionally considered the place of his awakening[1] Part of a series on Buddhism Outline · Portal History Timeline · Councils Gautama Buddha Disciples Later Buddhists Dharma or Concepts Four Noble Truths Dependent Origination Impermanence Suffering · Middle Way Non-self · Emptiness Five Aggregates Karma · Rebirth Samsara · Cosmology Practices Three Jewels Precepts · Perfections Meditation · Wisdom Noble Eightfold Path Wings to Awakening Monasticism · Laity Nirvāṇa Four Stages · Arhat Buddha · Bodhisattva Schools · Canons Theravāda · Pali Mahāyāna · Chinese Vajrayāna · Tibetan Countries and Regions Related topics Comparative studies Cultural elements Criticism v • d • e Buddhism (Pali/Sanskrit: बौद धमर Buddh Dharma) is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha (Pāli/Sanskrit "the awakened one"). The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE.[2] He is recognized by adherents as an awakened teacher who shared his insights to help sentient beings end suffering (or dukkha), achieve nirvana, and escape what is seen as a cycle of suffering and rebirth. Two major branches of Buddhism are recognized: Theravada ("The School of the Elders") and Mahayana ("The Great Vehicle"). Theravada—the oldest surviving branch—has a widespread following in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and Mahayana is found throughout East Asia and includes the traditions of Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon, Tendai and Shinnyo-en. In some classifications Vajrayana, a subcategory of Mahayana, is recognized as a third branch. -

The Jewish Museum in Prague

osobní, že bez dodatečné informace bývají větši- inscription of the names of the husband and wife Severočeským muzeem. Přednesené příspěvky history of Jewish communities in the area v Čechách dodnes skoro neznámé. nou jen obtížně rozpoznatelné. To je také důvod, (Fritz and Irma) and the wedding date byly zaměřeny na dějiny Židů v Čechách ve 20. occupied by Nazi Germany in 1938. The first part Výstava v Galerii Roberta Guttmanna, proč se ve specializovaných sbírkách téměř neob- (28 February 1926) on the back. All that is known století a na otázky výzkumu dějin židovských obcí of the proceedings includes chronological studies která potrvá až do 20. ledna 2008, před- jevují. Muzeu se nedávno podařilo získat darem of the original owners is that they perished during na území zabraném nacistickým Německem on topics from the First World War period through stavuje Feiglovu tvorbu v roce 100. výročí dva takovéto svatební přívěsky. Jedná se o porce- the Second World War. Both of these items v říjnu 1938. V první části sborníku jsou chronolo- to the end of the 1950s; the second part contains první výstavy Osmy a také 70 let po uměl- lánové střípky, zasazené do zlaté obruby s ouš- substantially enrich the Museum’s collection. gicky seřazené studie zpracovávající historická articles with a regional focus. The final paper cově poslední výstavě v Praze. kem. Na zadní straně jsou vyryta jména manželů témata od doby 1. světové války do konce 50. let deals with the Jewish history of Liberec. Na osobnost a tvorbu Bedřicha Feigla „Fritz“ a „Irma“ a datum svatby „28. -

Vztah Státu Ke Kultuře

Charles University in Prague Faculty of Philosophy & Arts Department of Cultural Studies THE APPROACH OF THE STATE TO CULTURE, CULTURAL POLICY OF THE COUNTRIES OF EUROPE (Updating of Selected Aspects) Intended exclusively for use by the MC CR Prague, March 2004 Collective of Authors: Mgr. Liana Bala PhDr. Václav Cimbál Doc. PhDr. Martin Matějů Gabriela Mrázová PhDr. Zdena Slavíková, CSc. PhDr. Martin Soukup Mgr. Barbara Storchová Mgr. Anna Šírová-Majkrzak PhDr. Zdeněk Uherek, CSc. PhDr. Josef Ţák 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 4 2 THE MODERN WORLD AND CULTURE ................................................................. 6 3 UNESCO AND CULTURAL DIVERSITY ................................................................. 12 4 DIVERSITY AND CREATIVITY ............................................................................... 15 5 THE CULTURAL POLICIES OF SELECTED COUNTRIES OF EUROPE ........ 19 5.1 SUMMARY OF THE CULTURAL POLICIES OF SELECTED COUNTRIES OF EUROPE ........ 40 5.2 ON THE PRIORITIES OF THE CULTURAL POLICIES OF THE COUNTRIES OF EUROPE ....... 47 6 CASE STUDIES ............................................................................................................. 49 6.1 THE CULTURAL POLICY OF AUSTRIA ........................................................................ 49 6.2 FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY – FOREIGN AND EDUCATIONAL POLICY ................ 56 6.3 SLOVAK REPUBLIC ...................................................................................................