Spis Treci 1.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Juraj Slăˇvik Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6n39p6z0 No online items Register of the Juraj Slávik papers Finding aid prepared by Blanka Pasternak Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2003, 2004 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Juraj Slávik 76087 1 papers Title: Juraj Slávik papers Date (inclusive): 1918-1968 Collection Number: 76087 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: Czech Physical Description: 54 manuscript boxes, 5 envelopes, 3 microfilm reels(23.5 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, speeches and writings, reports, dispatches, memoranda, telegrams, clippings, and photographs relating to Czechoslovak relations with Poland and the United States, political developments in Czechoslovakia, Czechoslovak emigration and émigrés, and anti-Communist movements in the United States. Creator: Slávik, Juraj, 1890-1969 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1976. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Juraj Slávik papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Alternative Form Available Also available on microfilm (51 reels). -

The Czechoslovak Exiles and Anti-Semitism in Occupied Europe During the Second World War

WALKING ON EGG-SHELLS: THE CZECHOSLOVAK EXILES AND ANTI-SEMITISM IN OCCUPIED EUROPE DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR JAN LÁNÍČEK In late June 1942, at the peak of the deportations of the Czech and Slovak Jews from the Protectorate and Slovakia to ghettos and death camps, Josef Kodíček addressed the issue of Nazi anti-Semitism over the air waves of the Czechoslovak BBC Service in London: “It is obvious that Nazi anti-Semitism which originally was only a coldly calculated weapon of agitation, has in the course of time become complete madness, an attempt to throw the guilt for all the unhappiness into which Hitler has led the world on to someone visible and powerless.”2 Wartime BBC broadcasts from Britain to occupied Europe should not be viewed as normal radio speeches commenting on events of the war.3 The radio waves were one of the “other” weapons of the war — a tactical propaganda weapon to support the ideology and politics of each side in the conflict, with the intention of influencing the population living under Nazi rule as well as in the Allied countries. Nazi anti-Jewish policies were an inseparable part of that conflict because the destruction of European Jewry was one of the main objectives of the Nazi political and military campaign.4 This, however, does not mean that the Allies ascribed the same importance to the persecution of Jews as did the Nazis and thus the BBC’s broadcasting of information about the massacres needs to be seen in relation to the propaganda aims of the 1 This article was written as part of the grant project GAČR 13–15989P “The Czechs, Slovaks and Jews: Together but Apart, 1938–1989.” An earlier version of this article was published as Jan Láníček, “The Czechoslovak Service of the BBC and the Jews during World War II,” in Yad Vashem Studies, Vol. -

Ivo PEJČOCH, Fašismus V Českých Zemích. Fašistické A

CENTRAL EUROPEAN PAPERS 2014 / II / 1 203 Ivo PEJČOCH Fašismus v českých zemích. Fašistické a nacionálněsocialistické strany a hnutí v Čechách a na Moravě 1922–1945 Praha: Academia 2011, 864 pages ISBN 978-80-200-1919-6 Critical review of Ivo Pejčoch’s book “Fascism in Czech countries. Fascist and national-so- cialist parties and movements in Bohemia and Moravia 1922-1945” The peer reviewed book written by Ivo Pejčoch, a historian working in the Military Historical Institute, was published by the Academia publishing house in 2011. The central topic of the monograph is, as the name suggests, mapping of the Czech fascism from the time of its origination in early 1920s through the period of Munich agreement and World War II to the year 1945. As the author mentions in preface, he restricts himself to the activity of organizations of Czech nation and language, due to extent limitation. The topic of the book picks up the threads of the earlier published monographs by Tomáš Pasák and Milan Nakonečný. But unlike Pasák’s book “Czech fascism 1922-1945 and col- laboration”, Ivo Pejčoch does not analyze fascism and seek causes of sympathies of a num- ber of important personalities to that ideology. On the contrary, his book rather presents a summary of parties, small parties and movements related to fascism and National Social- ism. He deals in more detail with the major ones - i.e. the Národní obec fašistická (National Fascist Community) or Vlajka (The Flag), but also for example the Kuratorium pro výchovu mládeže (Board for Youth Education) that was not a political party but, under the guid- ance of Emanuel Moravec, aimed at spreading the Roman-Empire ideas and influencing a large group of primarily young Protectorate inhabitants. -

Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938–1948

21 Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938 –1948 LUCIE ZADRAILOVÁ AND MILAN PECH 332 Lucie Zadražilová and Milan Pech Lucie Zadražilová (Skřivánková) is a curator at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, while Milan Pech is a researcher at the Institute of Christian Art at Charles University in Prague. Teir text is a detailed archival study of the activities of two Czech art institutions, the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague and the Mánes Association of Fine Artists, during the Nazi Protectorate era and its immediate aftermath. Te larger aim is to reveal that Czech cultural life was hardly dormant during the Protectorate, and to trace how Czech institutions negotiated the limitations, dangers, and interferences presented by the occupation. Te Museum of Decorative Arts cautiously continued its independent activities and provided otherwise unattainable artistic information by keeping its library open. Te Mánes Association of Fine Artists trod a similarly-careful path of independence, managing to avoid hosting exhibitions by representatives of Fascism and surreptitiously presenting modern art under the cover of traditionally- themed exhibitions. Tis essay frst appeared in the collection Konec avantgardy? Od Mnichovské dohody ke komunistickému převratu (End of the Avant-Garde? From the Munich Agreement to the Communist Takeover) in 2011.1 (JO) Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938–1948 In the light of new information gained from archival sources and contemporaneous documents it is becoming ever clearer that the years of the Protectorate were far from a time of cultural vacuum. Credit for this is due to, among other things, the endeavours of many people to maintain at least a partial continuity in public services and to achieve as much as possible within the framework of the rules set by the Nazi occupiers. -

GIPE-011912-05.Pdf

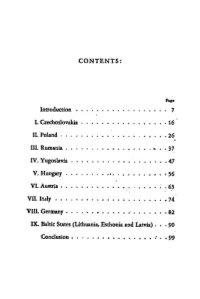

CONTENTS: Paco Introduction • • . 7 L Czechoslovakia . .J6 II. Poland .. • • 26 III. Rumania . ... • 37 IV. Yugoslavia . • • • •••• 47 V. Hungary ..• • • "'.. • "' • • • • . • , " l 56 VL Austtia ••. • • • • • ; • 6_5 VII. Italy ••• • ••• 74 VIII. Germany ••.•• •· • • • • 82 IX. Baltic States (Lithuania, Esthonia and latvia) . • • 90 Conclusion • • · . • • • • • • • , • • • • : • • 99 THE MILITARY J.MPORTANCE OF. CZECHOSLOVAKIA .IN EUROPE THE MILITARY IMPORTANCE OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA IN EUROPE COLONEL EMANUEL MORAVEC Profusor of tAe HigA Sclaool of War WitL. 8 Maps t 9 s a "Orl:.is" Printing and Pul:.lisl:.iog Co., Pregue l'BilfTBD BY «OABIB# l'B.A.GVlll li:II CZJtCHOBLOVA:&:IA. "If suc(.II!SS be achieved in uniting Austria with Germany, the collapse of Czechoslovakia will follow; Germany will then have common frontiers with Italy and Yugoslavia, and Italy will be strengthened against France." Ewald Banse in "Raum und Volk im Welt kriege", Edition of 1932. I BRIEF HISTORICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL OUTLINE The Rise of the Czechoslovak State After the defeat of the Central Powers at the end of October 1918 the Austro-Hungarian Empire fell asunder. The nations that had composed it either joined their kinsmen among the victorious Allied countries-Italy, Rumania and Yugoslavia--or formed new States. In this latter ma:nner arose Czechoslo vakia and Poland. Finally, there remained the racial· remnants of the old Monarchy-Austria with a Ger man population, and Hungary with a Magyar popu lation. The territories of the new Austria and Hun gary formed a central nationality zone in Central Europe touching the Italians on the West and the Ru manians on the East. North of this German-Magyar zone were the Slavonic nations forming the Republics· of Czechoslovakia and Poland. -

Czech Republic: the White Paper on Defence 2011

The White Paper on Defence The White Paper on Defence © The Ministry of Defence of the Czech Republic – DCP, 2011 The White Paper of Defence was approved by the Governmental Resolution of 18th May 2011, Nr. 369. Table of Contents Foreword by the Minister of Defence 6 Foreword by the Chief of General Staff 8 Commission for the White Paper on Defence 11 Key Findings and Recommendations 12 Traditions of the Armed Forces of the Czech Republic 22 Chapter 1 Doorways to the Future 26 The Government’s Approach to National Defence Building 26 Civilian Management and Democratic Control 29 Designation of Competencies and Responsibilities for Defence 29 Political-Military Ambitions 29 Legislative Framework 31 Chapter 2 Strategic Environment 34 Background 34 Czech Security Interests 38 Security Threats and Risks 39 Chapter 3 Roles and Functions of the Czech Armed Forces 44 Roles of the Czech Armed Forces 44 Functions in the Czech National and NATO Collective Defence 44 Functions in International Cooperation 46 Functions in Supporting Civilian Bodies 47 Chapter 4 Defence Planning 52 Chapter 5 Financial Framework and Management System 56 Macroeconomic Perspective 56 Microeconomic Perspective 59 Financial Management in an Austernity Era 66 Chapter 6 Competent and Motivated People 74 People are the Priority 74 Personnel Management 79 Career Management 81 Preparation of Personnel 84 Salary and Welfare Policy 87 Chapter 7 Development of Capabilities 92 Political-Military Ambitions and Capabilities 92 Capabilities Perspective of the Armed Forces 93 Capability-Based -

The Czechoslovak Government-In-Exile in London, 1939-1945

The Czechoslovak Government-In-Exile in London, 1939-1945 Iveta Danišová Bachelor´s Thesis 2017 ABSTRAKT Tato bakalářská práce zkoumá Československý zahraniční odboj a vládu v exilu mezi lety 1939-1945. Na začátku líčí historické pozadí a popisuje problémy Sudetských Němců. Poté se zabývá okolnostmi které předcházely Mnichovské dohodě. Dále se zabývá situací v Československu po podepsání Mnichovské dohody a odchodu vlády do exilu do Londýna. Bakalářská práce také zkoumá podmínky exilové vlády v Londýně, složení vlády, aktivity prezidenta Beneše a snahy vlády, aby byla oficiálně uznána ostatními národy jako právoplatná a jediná legislativní vláda Československa. Poté se zabývá poválečným návratem vlády zpět do Československa. Nakonec práce dokazuje, že úsilí členů exilové vlády ale také československých vojáků přispělo ke spáchání atentátu na Heydricha, ke konci druhé světové války a hlavně k anulování Mnichovské dohody, tudíž mohlo Československo získat po válce zpět své hranice. Klíčová slova: Československo, zahraniční odboj, vláda v exilu, Edvard Beneš, Velká Británie, Londýn, Německo, Mnichovská dohoda, Protektorát Čechy a Morava ABSTRACT This bachelor´s thesis examines the Czechoslovak foreign resistance and the government in exile between 1939 and 1945. It starts by providing the historical background and describing the problems of Sudeten Germans. Then it deals with the conditions that preceded the Munich Agreement. Next, it deals with the situation in Czechoslovakia after the signing the agreement and the departure of the government into exile in London. Moreover, the thesis documents the conditions faced by the government in London, the composition of the government, the activities of President Beneš and the government´s efforts to be officially recognized by other nations as the rightful and only government of Czechoslovakia. -

Sub-Saharan Africa in Czech Foreign Policy

CHAPTER 15 Chapter 15 Sub-Saharan Africa in Czech Foreign Policy Ondřej Horký-Hlucháň and Kateřina Rudincová FROM AN INTEREST IN AFRICA TO INTERESTS IN AFRICA?1 Back to Africa, but too late. This was the conclusion of the chapter devoted to Czech foreign policy towards Sub-Saharan Africa in the Yearbook of Czech Foreign Policy of the Institute of International Relations in 2012.2 Last year’s yearbook asserted that Czech foreign policy – in spite of budgetary austerity measures – had bounced off the bottom and attempted a “return to Africa”, which was, however, coming with a con- siderable delay. In 2013, this trend continued, characterized by the effort to deepen relations with traditional African partners, establish new relations or re-establish re- lations that had been put on ice. This effort was manifested in a 7% growth of Czech exports to the region. In a situation when the economic recession is still being felt in Europe, while Africa is experiencing record levels of economic growth, the awareness of the importance and possibilities of the African economy is growing faster than the crisis-struck foreign-policy tools of the Czech Republic may react. Most importantly, however, this interest in Africa is beginning to be felt by wider segments of Czech so- ciety, not merely the foreign policy actors, but gradually also foreign policy makers. It affects not only the media, but also the very companies that are seeking to expand their markets. The imported, but largely well-founded “Africa on the rise” fashion was, for example, also reflected in the employment of the term Emerging Africa in the names of both of the large and abundantly attended events organized by the MFA in 2013 on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Pan-African organization on the opportunities for Czech business on the African continent. -

17 October 2014 PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC

4th Cyber Security & 16th International ITTE Conference 2nd edition of Future Cyber Security & Defence Conference 11th edition of Advanced Technologies in Defence & Security Exhibition CONFERENCE ON IN CO-OPERATION WITH Future conflicts, risks, challenges and AFCEA Czech Chapter business opportunities National Security Authority of the Czech Republic National Centre of Cyber Security of the Czech Republic EXECUTIVE GUARANTOR Police Academy of the Czech Republic in Prague AFCEA Czech Cyber Security Working Group Armed Forces Academy of General Milan R. Štefánik, Slovakia University of Defence in Brno, Czech Republic Mr. Dušan Navrátil, LtGen. Petr Pavel, General (ret). Vlastimil Picek, Director, Czech National Chief, General Staff of the Defence Advisor to president Security Authority Czech Armed Forces of the Czech Republic UNIQUE GATHERING PLACE FOR EXPERTS 15 – 17 October 2014 PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC www.natoexhibition.org Under the Auspices of: In cooperation with: Specialised Technical Partners: partner: FUTURE CRISES 14 is a three-day international professional The conference is primarily aimed at the security and information conference divided into three sections accompanied by live dem- community of the public sector, armed and security forces, the onstration and simulation test area, professional workshop and academia and private business cooperating in projects of public Table-top exhibition of partners’ solutions and products. The interest. The conference is focused on developing international conference is a professional accompanying program of the inter- cooperation in cyber security in Europe, with special focus on the national defence and security exhibition FUTURE FORCES 2014. Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Hungary and Poland. The conference will be held in Prague, capital of the Czech Re- It is expected that about 250+ professionals from more than 50 public. -

Ve Čtvrtek 1. Ledna Se Minutu Po Půlnoci V Nemocnici V Rumburku Na Děčínsku Narodila Dívka Veronika

Ve čtvrtek 1. ledna se minutu po půlnoci v nemocnici v Rumburku na Děčínsku narodila dívka Veronika. Stala se tak první občankou v České republice narozenou v roce 2009. O minutu později přišel na svět chlapec Štěpán ve Slezské nemocnici v Opavě. Ve čtvrtek 14. ledna zemřel v Praze renomovaný architekt Jan Kaplický, kterému se ve stejný den narodila dcera Johanka. V dubnu by oslavil 72 let. V Česku se stal všeobecně známým díky kontroverznímu návrhu nové budovy Národní knihovny v Praze. Jan Kaplický zkolaboval na ulici nedaleko Vítězného náměstí v Praze a pokusy o jeho oživení však byly bezúspěšné. Jednasedmdesátiletý Kaplický žil trvale v Británii od roku 1968, kam emigroval z Československa. Doma ho pak proslavil návrh „chobotnice“, tedy stavby národní knihovny, která měla nahradit prostory v Klementinu. Dalším jeho českým projektem je stavba „rejnoka“, paláce kultury, který navrhl pro České Budějovice. Ten by měl pojmout až 1.400 lidí, počítá se s dvěma koncertními sály, restauracemi a kavárnami. Loni v říjnu se Kaplický stal prvním člověkem, který odmítl českou státní cenu. Ty každý rok uděluje ministerstvo kultury za přínos v oblasti literatury, divadla, hudby, výtvarného umění a architektury. Sedmičlenná porota mu cenu přiřkla za mimořádné architektonické dílo doma i v zahraničí. Jan Kaplický se narodil 18. dubna 1937 v Praze, kde také vystudoval Vysokou školu uměleckoprůmyslovou. Od své emigrace v roce 1968 dlouhodobě žil ve Velké Británii, kde v roce 1979 založil společně s Davidem Nixonem architektonické studio Future Systems. Svoji architekturu navrhoval ve stylu high-tech, v posledních letech experimentoval s organickou architekturou, která se inspiruje přírodními tvary. -

Equation Staggering Too Much 2 Interview with New Czech CHOD, LTG Petr Pavel

11/2012/2012 REVIEW NNewew CChiefhief ooff GGeneraleneral SStafftaff CCzechzech AArmedrmed FForcesorces LLieutenant-Generalieutenant-General PPetretr PPavel:avel: EEquationquation SStaggeringtaggering ttoooo mmuchuch 1 Contents An equation staggering too much 2 Interview with new Czech CHOD, LTG Petr Pavel Never step into the same river twice 6 Medics were the fi rst 12 Interactivities green-lit 14 Facing new challenges 17 Czech aid for Afghans 20 Four Czech years in Kabul 22 Cadets attained the jaguar 24 Managing oneself 27 A unique helicoper project 30 Minimi machinegun 32 LLieutenant-Generalieutenant-General PPetretr PPavelavel A school with no teachers 35 Czech MTA Hradiště turning into Logar 38 newly appointed the Chief of General Staff ”Hit!“ 40 Unique institute with mission out of the ordinary 43 of the Armed Forces of the Czech Republic Solving the puzzle of death 46 On Friday June 29, 2012, the President of your side,“ general In tune for missions in Afghanistan 48 the Czech Republic Václav Klaus appointed the Picek said to the Pre- new Chief of General Staff of the Armed Forces sident. The period of In the kingdoms of the mythic Scheherazadea 52 of the Czech Republic. Replacing General Vlas- time when he served timil Picek, Lieutenant-General Petr Pavel took as the Chief of the Firing at the Artic Circle 54 over as the new CHOD at July 1, 2012. Military Offi ce of the The Czech contribution to NAEW&C 58 The President congratulated both Generals, President gave him an and thanked General Picek for his achievements extensive experience The Balkan crucible 60 in the highest military post. -

Šéfredaktor Protektorátní Přítomnosti E

Masarykova univerzita Fakulta sociálních studií Šéfredaktor protektorátní Přítomnosti E. Vajtauer před Národním soudem E. Vajtauer, the editor in chief of protectorate „Přítomnost“, on the National court Diplomová práce Bc. Kristýna Maletová Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Pavel Večeřa, Ph.D. Brno 2015 Čestné prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedené v bibliografii. V Brně, dne 23. 12. 2015 …………………… 2 Poděkování Na tomto místě bych ráda poděkovala především vedoucímu diplomové práce panu PhDr. Pavlu Večeřovi, Ph.D., zejména za jeho trpělivost a cenné rady, kterými mi ochotně pomáhal řešit odborné a organizační problémy této práce. Ke zdárnému dokončení mi pomohla také podpora rodiny a zejména přítele, kteří mi dodávali povzbuzení vždy, když jsem potřebovala. 3 Anotace Diplomová práce „Šéfredaktor protektorátní Přítomnosti E. Vajtauer před Národním soudem“ se zabývá životními osudy Emanuela Vajtauera (*1892 – † ?), jednoho z předních představitelů skupiny tzv. aktivistických novinářů, kteří v době okupace kolaborovali s nacistickým Německem, a pojednává o soudním procesu z dubna roku 1947, jenž proběhl v nově obnoveném Československu v rámci poválečné retribuce, kdy byli před Národní soud postaveni ti, kteří svou činností v období existence protektorátu podporovali a propagovali nacistické hnutí. Autorka v úvodu práce zasazuje téma do historického kontextu, kdy přibližuje okolnosti vzniku Protektorátu Čechy a Morava, vysvětluje tehdejší tiskové poměry a věnuje se problematice kolaborace, aktivismu a následně i poválečného retribučního soudnictví. Stěžejní částí práce je pak komplexnější zachycení Vajtauerova života a činnosti, snaha dopátrat se konkrétních motivů, jež jej vedly k této kolaborační činnosti, a rekonstrukce soudního líčení. Emanuel Vajtauer byl v době nacistické okupace jedním z prominentních aktivistických šéfredaktorů, jenž byl následně Národním soudem uznán vinným ze zločinu proti státu a odsouzen k trestu smrti provazem.