Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938–1948

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Threshold of the Holocaust: Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms In

Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. of the Holocaust carried out by the local population. Who took part in these excesses, and what was their attitude towards the Germans? The Author Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms Were they guided or spontaneous? What Tomasz Szarota is Professor at the Insti- part did the Germans play in these events tute of History of the Polish Academy in Occupied Europe and how did they manipulate them for of Sciences and serves on the Advisory their own benefit? Delving into the source Board of the Museum of the Second Warsaw – Paris – The Hague – material for Warsaw, Paris, The Hague, World War in Gda´nsk. His special interest Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Kaunas, this comprises WWII, Nazi-occupied Poland, Amsterdam – Antwerp – Kaunas study is the first to take a comparative the resistance movement, and life in look at these questions. Looking closely Warsaw and other European cities under at events many would like to forget, the the German occupation. On the the Threshold of Holocaust ISBN 978-3-631-64048-7 GEP 11_264048_Szarota_AK_A5HC PLE edition new.indd 1 31.08.15 10:52 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. -

The Czechoslovak Exiles and Anti-Semitism in Occupied Europe During the Second World War

WALKING ON EGG-SHELLS: THE CZECHOSLOVAK EXILES AND ANTI-SEMITISM IN OCCUPIED EUROPE DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR JAN LÁNÍČEK In late June 1942, at the peak of the deportations of the Czech and Slovak Jews from the Protectorate and Slovakia to ghettos and death camps, Josef Kodíček addressed the issue of Nazi anti-Semitism over the air waves of the Czechoslovak BBC Service in London: “It is obvious that Nazi anti-Semitism which originally was only a coldly calculated weapon of agitation, has in the course of time become complete madness, an attempt to throw the guilt for all the unhappiness into which Hitler has led the world on to someone visible and powerless.”2 Wartime BBC broadcasts from Britain to occupied Europe should not be viewed as normal radio speeches commenting on events of the war.3 The radio waves were one of the “other” weapons of the war — a tactical propaganda weapon to support the ideology and politics of each side in the conflict, with the intention of influencing the population living under Nazi rule as well as in the Allied countries. Nazi anti-Jewish policies were an inseparable part of that conflict because the destruction of European Jewry was one of the main objectives of the Nazi political and military campaign.4 This, however, does not mean that the Allies ascribed the same importance to the persecution of Jews as did the Nazis and thus the BBC’s broadcasting of information about the massacres needs to be seen in relation to the propaganda aims of the 1 This article was written as part of the grant project GAČR 13–15989P “The Czechs, Slovaks and Jews: Together but Apart, 1938–1989.” An earlier version of this article was published as Jan Láníček, “The Czechoslovak Service of the BBC and the Jews during World War II,” in Yad Vashem Studies, Vol. -

Ivo PEJČOCH, Fašismus V Českých Zemích. Fašistické A

CENTRAL EUROPEAN PAPERS 2014 / II / 1 203 Ivo PEJČOCH Fašismus v českých zemích. Fašistické a nacionálněsocialistické strany a hnutí v Čechách a na Moravě 1922–1945 Praha: Academia 2011, 864 pages ISBN 978-80-200-1919-6 Critical review of Ivo Pejčoch’s book “Fascism in Czech countries. Fascist and national-so- cialist parties and movements in Bohemia and Moravia 1922-1945” The peer reviewed book written by Ivo Pejčoch, a historian working in the Military Historical Institute, was published by the Academia publishing house in 2011. The central topic of the monograph is, as the name suggests, mapping of the Czech fascism from the time of its origination in early 1920s through the period of Munich agreement and World War II to the year 1945. As the author mentions in preface, he restricts himself to the activity of organizations of Czech nation and language, due to extent limitation. The topic of the book picks up the threads of the earlier published monographs by Tomáš Pasák and Milan Nakonečný. But unlike Pasák’s book “Czech fascism 1922-1945 and col- laboration”, Ivo Pejčoch does not analyze fascism and seek causes of sympathies of a num- ber of important personalities to that ideology. On the contrary, his book rather presents a summary of parties, small parties and movements related to fascism and National Social- ism. He deals in more detail with the major ones - i.e. the Národní obec fašistická (National Fascist Community) or Vlajka (The Flag), but also for example the Kuratorium pro výchovu mládeže (Board for Youth Education) that was not a political party but, under the guid- ance of Emanuel Moravec, aimed at spreading the Roman-Empire ideas and influencing a large group of primarily young Protectorate inhabitants. -

Resistance, Collaboration, Adaptation… Some Notes on the Research of the Czech Society in the Protectorate

Resistance, Collaboration, Adaptation… Some Notes on the Research of the Czech Society in the Protectorate Stanislav Kokoška Following the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, the popu- lation of the Czech Lands was divided into three basic categories. Germans, the high- est category, became full Reich citizens; Czechs, who according to the Nazi le- gal expert Wilhelm Stuckart “were rather inhabitants of a peculiar kind”1 made up the second category; and fi nally in a third category were the Jews, to whom the Nuremberg Laws were soon applied and who therefore had no citizen rights. The fates of these population groups diverged and took different courses depending on the changing character of Nazi occupation policy and the restrictive measures introduced during the war. Czech historiography has yet to engage with questions of social change dur- ing the Second World War in any comprehensive way. For many years Czech his- toriography of the period focused rather narrowly on the repressive basis and policies of the Nazi occupying power and on the theme of the Czech resistance 1 KÁRNÝ, Miroslav – MILOTOVÁ, Jaroslava: Anatomie okupační politiky hitlerovského Německa v Protektorátu Čechy a Morava [Anatomy of the Occupation Policy of Germany in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia]. In: HERMAN, Karel (ed.): Sborník k prob- lematice dějin imperialismu [Collection on the Theme of the History of Imperialism], vol. 21: Anatomie okupační politiky hitlerovského Německa v „Protektorátu Čechy a Morava“. Dokumenty z období říšského protektora Konstantina von Neuratha [Anatomy of the Occu- pation Policy of Hitler’s Germany in the “Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia”. -

GIPE-011912-05.Pdf

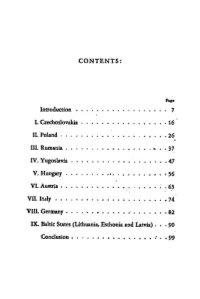

CONTENTS: Paco Introduction • • . 7 L Czechoslovakia . .J6 II. Poland .. • • 26 III. Rumania . ... • 37 IV. Yugoslavia . • • • •••• 47 V. Hungary ..• • • "'.. • "' • • • • . • , " l 56 VL Austtia ••. • • • • • ; • 6_5 VII. Italy ••• • ••• 74 VIII. Germany ••.•• •· • • • • 82 IX. Baltic States (Lithuania, Esthonia and latvia) . • • 90 Conclusion • • · . • • • • • • • , • • • • : • • 99 THE MILITARY J.MPORTANCE OF. CZECHOSLOVAKIA .IN EUROPE THE MILITARY IMPORTANCE OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA IN EUROPE COLONEL EMANUEL MORAVEC Profusor of tAe HigA Sclaool of War WitL. 8 Maps t 9 s a "Orl:.is" Printing and Pul:.lisl:.iog Co., Pregue l'BilfTBD BY «OABIB# l'B.A.GVlll li:II CZJtCHOBLOVA:&:IA. "If suc(.II!SS be achieved in uniting Austria with Germany, the collapse of Czechoslovakia will follow; Germany will then have common frontiers with Italy and Yugoslavia, and Italy will be strengthened against France." Ewald Banse in "Raum und Volk im Welt kriege", Edition of 1932. I BRIEF HISTORICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL OUTLINE The Rise of the Czechoslovak State After the defeat of the Central Powers at the end of October 1918 the Austro-Hungarian Empire fell asunder. The nations that had composed it either joined their kinsmen among the victorious Allied countries-Italy, Rumania and Yugoslavia--or formed new States. In this latter ma:nner arose Czechoslo vakia and Poland. Finally, there remained the racial· remnants of the old Monarchy-Austria with a Ger man population, and Hungary with a Magyar popu lation. The territories of the new Austria and Hun gary formed a central nationality zone in Central Europe touching the Italians on the West and the Ru manians on the East. North of this German-Magyar zone were the Slavonic nations forming the Republics· of Czechoslovakia and Poland. -

Buddhism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search

Buddhism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A statue of Gautama Buddha in Bodhgaya, India. Bodhgaya is traditionally considered the place of his awakening[1] Part of a series on Buddhism Outline · Portal History Timeline · Councils Gautama Buddha Disciples Later Buddhists Dharma or Concepts Four Noble Truths Dependent Origination Impermanence Suffering · Middle Way Non-self · Emptiness Five Aggregates Karma · Rebirth Samsara · Cosmology Practices Three Jewels Precepts · Perfections Meditation · Wisdom Noble Eightfold Path Wings to Awakening Monasticism · Laity Nirvāṇa Four Stages · Arhat Buddha · Bodhisattva Schools · Canons Theravāda · Pali Mahāyāna · Chinese Vajrayāna · Tibetan Countries and Regions Related topics Comparative studies Cultural elements Criticism v • d • e Buddhism (Pali/Sanskrit: बौद धमर Buddh Dharma) is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha (Pāli/Sanskrit "the awakened one"). The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE.[2] He is recognized by adherents as an awakened teacher who shared his insights to help sentient beings end suffering (or dukkha), achieve nirvana, and escape what is seen as a cycle of suffering and rebirth. Two major branches of Buddhism are recognized: Theravada ("The School of the Elders") and Mahayana ("The Great Vehicle"). Theravada—the oldest surviving branch—has a widespread following in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and Mahayana is found throughout East Asia and includes the traditions of Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon, Tendai and Shinnyo-en. In some classifications Vajrayana, a subcategory of Mahayana, is recognized as a third branch. -

The Dc-Nazilication Law of 5Th March, 1946, However, Passed for Bavaria

202 PUNISHMENT OF CRIMINALS “ The Dc-Nazilication Law of 5th March, 1946, however, passed for Bavaria, Greatcr-Hcsse and Wurttcmbcrg-Badcn, provides definite sentences lor punishment in each type of olfencc. The Tribunal recommends that in no case should punishment imposed under Law No. 10 upon any members of an organisation or group declared by the Tribunal to be criminal exceed the punishment lixed by the D enazifica tion Law.(') The Dc-Nazilication Law of 5th March, 1946, referred to by the Tribunal, was in force in the United States Zone and, as far as restriction of personal liberty is concerned, its heaviest penalty did not exceed 10 years’ imprison ment. There were also provisions for confiscation of property and depriva tion of civil rights. As a study of the sentences passed by the United States Military Tribunal in Nuremberg for the crime of membership shows, these Tribunals have in fact followed the recommendation of the International Military Tribunal.^2) It may be also pointed out that for committing crimcs against humanity (a category more recently evolved and recognised as olfcnces than war crimcs), the accused Rothaug, who had been found guilty of no other types of crimcs, was sentenced by the Military Tribunal which conducted the Justicc Trial not to death but to life imprisonment, although many of his victims had suffered dcath.l3) On the other hand the International Military Tribunal sentenced to death Julius Strcichcr after finding him guilty on the one count of crimcs against humanity, which however involved many deaths.(4) It is thought that an interesting study could be made of the different types and degrees of severity of penalties passed on persons found guilty of different ofTcnccs under international law by Courts acting within the limits laid down by that law as to the punishment of criminals. -

Spis Treci 1.Indd

Zeszyty Naukowe ASzWoj nr 2(111) 2018 War Studies University Scientific Quarterly no. 2(111) 2018 ISSN 2543-6937 THE DEFENCE SECTOR AND ITS EFFECT ON NATIONAL SECURITY DURING THE CZECHOSLOVAK (MUNICH) CRISIS 1938 Aleš BINAR, PhD University of Defence in Brno Abstract The Czechoslovak (Munich) Crisis of 1938 was concluded by an international conference that took place in Munich on 29-30 September 1938. The decision of the participating powers, i.e. France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom, was made without any respect for Czechoslovakia and its representatives. The aim of this paper is to examine the role of the defence sector, i.e. the representatives of the ministry of defence and the Czechoslovak armed forces during the Czechoslovak (Munich) Crisis in the period from mid-March to the beginning of October 1938. There is also a question as to, whether there are similarities between the position then and the present-day position of the army in the decision-making process. Key words: Czechoslovak (Munich) Crisis, Munich Agreement, 1938, Czechoslovak Army, national security. Introduction The agreement in Munich (München), where the international conference took place on 29–30 September 1938, represents a crucial crossroads in the history of Czechoslovakia. By accepting the Munich Agreement, Czechoslovak President, Edvard Beneš, and representatives of his government made a decision that affected the nation not only for the next few years, but for decades thereafter. This so-called Munich Syndrome, then, is infamously blamed by many in Czechoslovak society for the fascist-like orientation of the so-called the Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–1939) and the acceptance of the Communist coup d’état of 1948. -

Nazi Party from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Nazi Party From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the German Nazi Party that existed from 1920–1945. For the ideology, see Nazism. For other Nazi Parties, see Nazi Navigation Party (disambiguation). Main page The National Socialist German Workers' Party (German: Contents National Socialist German Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (help·info), abbreviated NSDAP), commonly known Featured content Workers' Party in English as the Nazi Party, was a political party in Germany between 1920 and 1945. Its Current events Nationalsozialistische Deutsche predecessor, the German Workers' Party (DAP), existed from 1919 to 1920. The term Nazi is Random article Arbeiterpartei German and stems from Nationalsozialist,[6] due to the pronunciation of Latin -tion- as -tsion- in Donate to Wikipedia German (rather than -shon- as it is in English), with German Z being pronounced as 'ts'. Interaction Help About Wikipedia Community portal Recent changes Leader Karl Harrer Contact page 1919–1920 Anton Drexler 1920–1921 Toolbox Adolf Hitler What links here 1921–1945 Related changes Martin Bormann 1945 Upload file Special pages Founded 1920 Permanent link Dissolved 1945 Page information Preceded by German Workers' Party (DAP) Data item Succeeded by None (banned) Cite this page Ideologies continued with neo-Nazism Print/export Headquarters Munich, Germany[1] Newspaper Völkischer Beobachter Create a book Youth wing Hitler Youth Download as PDF Paramilitary Sturmabteilung -

EAGLE GLASSHEIM Genteel Nationalists: Nobles and Fascism in Czechoslovakia

EAGLE GLASSHEIM Genteel Nationalists: Nobles and Fascism in Czechoslovakia in KARINA URBACH (ed.), European Aristocracies and the Radical Right 1918-1939 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007) pp. 149–160 ISBN: 978 0 199 23173 7 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 9 Genteel Nationalists: Nobles and Fascism in Czechoslovakia EAGLE GLASSHEIM In the early years of the twentieth century, the Bohemian nobility still occupied the heights of Habsburg society and government. Around 300 families of the high aristocracy owned almost a third of the Bohemian crown lands, not to mention vast investments in finance and industry. Though forced to share power with the emperor and increasingly assertive popular forces, Bohemian nobles regularly served as prime ministers, generals, bishops, and representatives in the upper house of parliament. All this would change in 1918. Weakened by defeat in war and the nationalist demands of its eleven subject peoples, the Habsburg monarchy dissolved as the First World War drew to an end. -

Šéfredaktor Protektorátní Přítomnosti E

Masarykova univerzita Fakulta sociálních studií Šéfredaktor protektorátní Přítomnosti E. Vajtauer před Národním soudem E. Vajtauer, the editor in chief of protectorate „Přítomnost“, on the National court Diplomová práce Bc. Kristýna Maletová Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Pavel Večeřa, Ph.D. Brno 2015 Čestné prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedené v bibliografii. V Brně, dne 23. 12. 2015 …………………… 2 Poděkování Na tomto místě bych ráda poděkovala především vedoucímu diplomové práce panu PhDr. Pavlu Večeřovi, Ph.D., zejména za jeho trpělivost a cenné rady, kterými mi ochotně pomáhal řešit odborné a organizační problémy této práce. Ke zdárnému dokončení mi pomohla také podpora rodiny a zejména přítele, kteří mi dodávali povzbuzení vždy, když jsem potřebovala. 3 Anotace Diplomová práce „Šéfredaktor protektorátní Přítomnosti E. Vajtauer před Národním soudem“ se zabývá životními osudy Emanuela Vajtauera (*1892 – † ?), jednoho z předních představitelů skupiny tzv. aktivistických novinářů, kteří v době okupace kolaborovali s nacistickým Německem, a pojednává o soudním procesu z dubna roku 1947, jenž proběhl v nově obnoveném Československu v rámci poválečné retribuce, kdy byli před Národní soud postaveni ti, kteří svou činností v období existence protektorátu podporovali a propagovali nacistické hnutí. Autorka v úvodu práce zasazuje téma do historického kontextu, kdy přibližuje okolnosti vzniku Protektorátu Čechy a Morava, vysvětluje tehdejší tiskové poměry a věnuje se problematice kolaborace, aktivismu a následně i poválečného retribučního soudnictví. Stěžejní částí práce je pak komplexnější zachycení Vajtauerova života a činnosti, snaha dopátrat se konkrétních motivů, jež jej vedly k této kolaborační činnosti, a rekonstrukce soudního líčení. Emanuel Vajtauer byl v době nacistické okupace jedním z prominentních aktivistických šéfredaktorů, jenž byl následně Národním soudem uznán vinným ze zločinu proti státu a odsouzen k trestu smrti provazem. -

Žurnalisté Mezi Zradou a Kolaborací Moravská Novinářská Kolaborace Před Národním Soudem Oravská Novinářská K O

a ř e č vel Ve a P laborací dním soudem o o laborace před Nár laborace před o Žurnalisté mezi zradou a kolaborací Moravská novinářská kolaborace před Národním soudem oravská novinářská k Žurnalisté mezi zradou a k M Pavel Večeřa Masarykova univerzita Žurnalisté mezi zradou a kolaborací Moravská novinářská kolaborace před Národním soudem Pavel Večeřa Žurnalisté mezi zradou a kolaborací Moravská novinářská kolaborace před Národním soudem Pavel Večeřa Masarykova univerzita Brno 2014 „Edice: Media“ Tato publikace vznikla v rámci projektu OP VK s názvem „Internacionalizace, inovace, praxe: sociálně-vědní vzdělávání pro 21. století“ a registračním číslem CZ.1.07/2.2.00/28.0225. Plný text publikace v interaktivním formátu pdf a ve formátu pro čtečky je k dispozici na stránkách http://www.munimedia.cz/book/. Odborně posoudil: PhDr. Jakub Končelík, Ph.D. Jazyková redakce: Mgr. Radovan Plášek © 2014 Pavel Večeřa © 2014 Masarykova univerzita Publikace podléhá licenci Creative Commons: CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Uveďte autora-Neužívejte dílo komerčně-Nezasahujte do díla 3.0 Česko) ISBN 978-80-210-7506-1 ISBN 978-80-210-7507-8 (online : pdf) ISBN 978-80-210-7508-5 (online : ePub) OBSAH I. SLOVO ÚVODEM 11 II. MEZI KONFORMISTICKOU A AKTIVISTICKOU KOLABORACÍ 19 1. Fenomén kolaborace .................................................................19 2. Novinářská kolaborace v protektorátu Čechy a Morava ................................23 3. Typy kolaborace, zrada a denunciace .................................................26 4. Retribuční zákonodárství a Národní soud .............................................30 III. ŽIVOT A DÍLO NOVINÁŘŮ-KOLABORANTŮ Z MORAVY 35 1. Původ, rodinné poměry a vzdělání ....................................................35 2. Na prahu životních rozhodnutí ........................................................37 3. Novináři republiky ....................................................................41 4. K metě šéfredaktora ..................................................................57 5.