Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spirits Catalog

SPIRITS CATALOG WWW.CNSIMPORTSCA.COM [email protected] PH: 626 579 9018 | FAX: 626 579 0584 TABLE OF CONTENTS Whiskey 1 Liqueurs 10 Vodka 5 Asian Beers 13 Gin 6 Baijiu 14 Tequilla 7 Terms & Conditions 16 Mezcal 8 Return Policy 17 Rum 9 WHISKEY AMERICAN DRIFTLESS GLEN DRIFTLESS GLEN STRAIGHT RYE WHISKEY STRAIGHT BOURBON WHISKEY SINGLE BARREL SINGLE BARREL (Barrel Program Available) (Barrel Program Available) Origin: Baraboo, WI Origin: Baraboo, WI Mash: 80% Rye, 10% Malted Barley, 10% Corn Mash: 60% Corn, 20% Malted Barley, 20% Rye Nose: Cinnamon, Hints of Oak Nose: Vanilla, Honey, Light Spices Tongue: Spicy Rye, Honey Tongue: Buttered Popcorn, Raw Corn Husk, Rye Spice Finish Accolades: Silver - WSWA 2017 ABV 48% Size: 750ML ABV 48% Size: 750ML DRIFTLESS GLEN DRIFTLESS GLEN RYE WHISKEY BOURBON WHISKEY Origin: Baraboo, WI Origin: Baraboo, WI Mash: 80% Rye, 10% Malted Barley, 10% Corn Mash: 60% Corn, 20% Rye, 20% Malted Barley Nose: White pepper, Burnt Oak Nose: Vanilla, Caramel Corn Tongue: Spicy Vanilla, Honey Tongue: Light Molasses, Brown Sugar Toffee ABV 48% Size: 750ML ABV 48% Size: 750ML INDIAN RAMPUR INDIAN SINGLE VINN WHISKEY MALT WHISKY DOUBLE CASK Origin: Wilsonville, OR Origin: Rampur, India Mash: 100% Long Grain Rice Mash: 100% Indian Malted Barley Nose: Toffee, Fruit Gummies Nose: Tropical Fruit, Deep Malt, Oak Tongue: Sweet, Tapioca, Spicy Cocoa Tongue: Sherry, Rich Fruit ABV 43% Size: 375ML/750ML ABV 45% Size: 750ML 1 Spirits Catalog 2019 WHISKEY JAPANESE RAMPUR INDIAN SINGLE KUJIRA MALT WHISKY RYUKYU WHISKY 20 YEAR Origin: -

World's Best Wines & Spirits

ULTIMATE BEVERAGE CHALLENGE ULTIMATE GUIDE TO THE WORLD’S BEST WINES & SPIRITS 2019 PUBLISHED JOINTLY BY BEVERAGE MEDIA GROUP & ULTIMATE BEVERAGE CHALLENGE CONGRATULATIONS TO THIS YEAR’S HIGH-SCORING WINES Chateau Malbec Chateau Ferrande Chateau Haut Surget Louis Laurent Tour Prignac Chateau Barreyres 2016 Bordeaux 2016 Graves 2015 Lalande de 2018 Rosé d’Anjou Grand Reserve 2016 Haut-Medoc 94 - FINALIST 93 - FINALIST Pomerol 93 - FINALIST 2016 Medoc 91 GREAT VALUE GREAT VALUE 93 - FINALIST GREAT VALUE 92 Aime Roquesante Chateau D’Arcins Chateau Tour Maison Castel Michel Lelu 2018 Cotes du 2015 Haut-Medoc Prignac Grande Reserve Muscadet Provence Rosé 90 2015 Medoc Cabernet Sauvignon 2018 Loire Valley 90 - TRIED & TRUE 90 2017 Pays d’Oc 90 - GREAT VALUE 90 Imported by Luneau USA Inc. Westport, CT LuneauUSA.com CONGRATULATIONS TO THIS YEAR’S HIGH-SCORING WINES ULTIMATE BEVERAGE CHALLENGE 2019 IDENTIFYING THE WORLD’S BEST WINES, SPIRITS & SAKES LIKE NO OTHER COMPETITION Ultimate Guide to the World’s Best Wines and Spirits features the At Ultimate Spirits Challenge® (USC) the quality highest-scoring results from Ultimate Beverage Challenge’s® (UBC) rankings for every category for spirits are determined two major international beverage competitions held in 2019: Ultimate with uncommon skill and precision by all-star Ultimate Spirits Challenge® (USC) and Ultimate Wine Challenge® (UWC). Spirits Challenge judging panels convened by USC So, since 2010, why has UBC become the beverage industry’s most Judging Director F. Paul Pacult, whom Forbes. trusted and respected evaluation company? Answers UBC’s Judging com called, “America’s foremost spirits authority”. Chateau Malbec Chateau Ferrande Chateau Haut Surget Louis Laurent Tour Prignac Chateau Barreyres Chairman and Co-Founder F. -

Yes, Chef… Hip to Be Square

CUISINE / WINE / ART LP4 [email protected] Yes, Chef… While roast goose is a traditional dish on Christmas menus around the world, Chiu Chow marinated goose has been the signature dish of Chan Kan Kee since 1948 – and it hasn’t changed since, with a unique recipe that’s a family secret passed down through the generations. Since 2010, Eliza Chan and her elder sister, Rebecca, are part of the third generation to run the restaurant. Here, they unveil some of the secrets of this delicious dish photos by Calvin Ng were a lot of hawker stalls like ours. Chiu Chow Marinated Goose Can you share any of For the lushui (stock) fry them for a bit. After that, add the water, the secrets of your 1.5kg pork belly (if making new lushui) light soy sauce and dark soy sauce. family’s recipe? 19g Sichuan pepper Bring the stock to a boil, then pour it into For one, we use galangal 10 pieces star anise a stock pot. Boil on low heat for 30 minutes to instead of regular Chinese 75g cinnamon/cassia sticks retain its quality; high heat will make the sauce ginger. In addition, Chan 300ml light soy sauce overly concentrated and it will be too salty. Kan Kee’s lushui [stock for 75ml dark soy sauce Add the meat (goose, duck, or pork) that marinating] was started in 300g crystal/rock sugar you’d like to marinate into the stock. If you’re 1948 by my grandfather. 8 slices galangal using a smaller pot at home, chop the goose Over all these 72 years, 150g leeks or duck into smaller pieces (i.e. -

Taiwan Food Processing Ingredients Enter a Descriptive Report Name

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 12/18/2015 GAIN Report Number: TW15044 Taiwan Food Processing Ingredients Enter a Descriptive Report Name Approved By: Mark Ford Prepared By: Cindy Chang Report Highlights: extremely competitive, there are still great opportunities for U.S. exporters. U.S. exports of high value food products to Taiwan reached US$1.3 billion in 2014 and this trend is expected to continue for the next several years. Imports of premium food items from other countries has been increasing, but U.S. products continue to be well-accepted by Taiwan consumers due to competitive prices and consumer confidence in the quality and safety of U.S. food products. Taiwan is the United States’ seventh largest agricultural export market due in part to the great success in the food processing and ingredients sector. Post: Taipei ATO Executive Summary: SECTION I. MARKET SUMMARY Taiwan Food Processing and Ingredients Sector Overview and Trends Opportunities exist to expand U.S. food product sales to Taiwan’s food processing and ingredient sector. Given Taiwan’s current size and population, the country will continue the trend of looking overseas for food processing and ingredients. In 2014, Taiwan’s agricultural industry accounts for less than 2% of GDP and only 5% of employment in Taiwan. Taiwan’s food processing and ingredients industry is comprised of the following major sectors: beverage, coffee/cocoa, condiments/seasonings, dairy products, fats/oils, flour/ bakery products, fruits/vegetables, meat/poultry products, snack foods, and sugar and confectionery. -

Kaoliang and the Ganbei Culture “A Thousand Cups of Wine Do Not Suffice When True Friends Meet, but Half a Sentence Is Too Much When There Is No Meeting of Minds.”

T AIPEI UNCORKED Kaoliang and The Ganbei Culture “A thousand cups of wine do not suffice when true friends meet, but half a sentence is too much when there is no meeting of minds.” MARK L. PETERSON (Chinese Proverb) rinking for pleasure and daredevil drinking has after every course at a banquet and guests are often asked historically been part of Taiwan’s culture for to have one drink with every person who is considered who-knows-how-long. Recently, favored liquid a host. According to a Chinese proverb, “if you leave a D refreshments from abroad have included XO social meal sober you did not truly enjoy yourself,” which brandies, Scotch whiskeys, and in the past few years the is rather paradoxical considering the Chinese frown upon Taiwanese have acquired a seemingly unquenchable enthusiasm drunkenness. Even though ganbei toasts are offered for Western-style wine. Red wine in particular has become throughout the night, you only have to empty your glass once synonymous with ‘class’ and healthier drinking during on the first toast when all drain their glasses and show each weddings, restaurant dining, pub hopping, and entertaining other the traditional empty cup (ladies are supposed to take at home. Enjoying red wine has become the passion des only a sip). The Chinese generally don’t touch glasses with personnes in such a big way that France’s five largest wine each other during a toast. producers now come to Taiwan every year to promote sales. While the specific ‘tastes’ of Taiwanese may change TAIWAN FIRE-WATER with fashion, one thing never changes: the culture of ganbei On the front-line island of Kinmen, where the local specialty (literally ‘dry glass,’ requiring drinkers to consume every last is kaoliang, a unique drinking culture has taken shape. -

The Duty Free & Travel Retail Asia Pacific Summit

6 - 10 MAY 2018 - SINGAPORE The Duty Free & Travel Retail Asia Pacific Summit Introducing TFWA • Asia Pacific Market • TFWA Asia Pacific Exhibition & Conference • Programme • Why exhibit? • Why visit? • Conference & Workshops • ONE2ONE • Key tools • Networking • Contact Tax Free World Association 2 Introducing TFWA • Asia Pacific Market • TFWA Asia Pacific Exhibition & Conference • Programme • Why exhibit? • Why visit? • Conference & Workshops • ONE2ONE • Key tools • Networking • Contact 3 Introducing TFWA • Asia Pacific Market • TFWA Asia Pacific Exhibition & Conference • Programme • Why exhibit? • Why visit? • Conference & Workshops • ONE2ONE • Key tools • Networking • Contact With over 500 members, TFWA (Tax Free World Association) is the world’s biggest duty free and travel retail association. Its mission – summarised by its motto ‘by the trade, for the trade’ – is to identify trends and opportunities; build awareness; and provide a business platform for the global duty free and travel retail industry to prosper. TFWA’s key activities are organising exhibitions, delivering specialist conferences and workshops, and commissioning relevant and informative consumer research studies. 4 Introducing TFWA • Asia Pacific Market • TFWA Asia Pacific Exhibition & Conference • Programme • Why exhibit? • Why visit? • Conference & Workshops • ONE2ONE • Key tools • Networking • Contact Asia Pacific Market Asia Pacific: the engine of duty free & travel retail 5 Introducing TFWA • Asia Pacific Market • TFWA Asia Pacific Exhibition & Conference • Programme • Why exhibit? • Why visit? • Conference & Workshops • ONE2ONE • Key tools • Networking • Contact Asia Pacific is the undisputedgrowth driver of the global duty free & travel retail industry, as the region proved once again in 2016. During a year in which other regions posted flat or negative growth, sales in Asia Pacific increased by 9.1% in US$ at current rates, according to preliminary figures from Generation Research. -

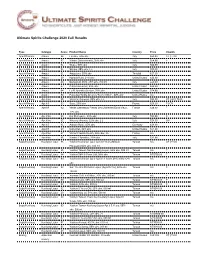

Ultimate Spirits Challenge 2020 Full Results

Ultimate Spirits Challenge 2020 Full Results Type Subtype Score Product Name Country Price Awards Aperitif/Amaro Amaro 94 Lucano, 28% abv Italy $30.00 CT | T100 Aperitif/Amaro Amaro 92 Nonino Quintessentia, 35% abv Italy $54.99 F Aperitif/Amaro Amaro 91 Silano, 30% abv Italy $24.99 Aperitif/Amaro Amaro 91 Sibona, 28% abv, 1 L Italy $30.00 Aperitif/Amaro Amaro 91 Angostura, 35% abv Trinidad $27.99 Aperitif/Amaro Amaro 89 Hypatia Rubi, 24% abv United States $39.00 Aperitif/Amaro Amaro 88 Bertagnolli 1870, 27% abv, 700 ml Italy €20.00 Aperitif/Amaro Amaro 87 California Fernet, 40% abv United States $39.99 Aperitif/Amaro Amaro 84 Lo-Fi Aperitifs Gentian, 20% abv United States $24.99 Aperitif/Amaro Amaro 84 Founding Spirits Arroyo's "Never Bitter" , 22% abv United States n/a Aperitif/Amaro Aperitivo 95 Vincenzi Capasso, 22% abv, 1 L Italy $24.99 CT | GV | T100 Aperitif/Amaro Aperitif 93 Suze, 20% abv France $24.99 F | GV Aperitif/Amaro Aperitif 93 Merlet Chevessac Pineau des Charentes Extra Vieux, France $36.00 F 17% abv Aperitif/Amaro Aperitivo 93 Del Professore, 15% abv Italy $30.99 F Aperitif/Amaro Aperitivo 92 Vincenzi Arancia, 11% abv, 1 L Italy $24.99 GV Aperitif/Amaro Aperitif 91 Asbach Rose, 15% abv Germany $24.99 Aperitif/Amaro Aperitif 90 Dubonnet, 19% abv United States $17.99 Aperitif/Amaro Aperitivo 87 Vincenzi Bellini Peach, 18% abv, 1 L France n/a Aperitif/Amaro Aperitivo 86 Nonino L'Aperitivo, 21% abv Italy $31.99 Baijiu/Kaoliang Kaoliang Liquor 96 Yushan Kaoliang Liquor Aged 8 Years (Mikado Taiwan n/a CT | T100 Pheasant) 56% -

Enterprise Innovation Marketing and Counseling Diagnosis-Taking

Enterprise Innovation Marketing and Counseling Diagnosis-Taking Kinmen Royal Liquor as Example Hao-Wei Yang Kai-Fu Yang Hsiao-Tung Liang Chunh-Hong Kuo Chaoyang University of (Corresponding Author) Chaoyang University of Chaoyang University of Technology Chaoyang University of Technology Technology 168, Jifeng E. Rd., Wufeng Technology 168, Jifeng E. Rd., Wufeng 168, Jifeng E. Rd., Wufeng District, Taichung, 41349 168, Jifeng E. Rd., Wufeng District, Taichung, 41349 District, Taichung, 41349 Taiwan, R.O.C. District, Taichung, 41349 Taiwan, R.O.C. Taiwan, R.O.C. 0987-276-858, 886 Taiwan, R.O.C. 0988-263-660, 886 0972-138-688, 886 [email protected] 0958-939-246, 886 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT hand with mainland liquor and expand to a huge market on the Since Taiwan abolished the tobacco and alcohol monopoly system other side. However, under the influence of the big environment, in 2002, the market for tobacco and alcohol has been open to the the market is gradually shrinking, coupled with a large inventory, public. Whether it is a public winery or a private winery, it must forcing considerable performance to gradually evolve into a crisis not only face the competition of imported liquor, but also face the (Jianghe, 2016). Kinmen Royal Liquor used to be a completely attack of foreign opponents. For the challenges and obstacles, producer-oriented and the business philosophy of the distribution Kinmen Royal Liquor must find the superior ability to ensure model, but in this era of consumer-oriented seems to need to make sustainable operation and maintain good competitiveness in the some adjustments in order to be invincible. -

Cultural Adjustment of High School Teachers from Taiwan in Kinmen

Cultural Adjustment of High School Teachers from Taiwan in Kinmen by Hsin-Lan Wu A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Major: International Human Resource Development Advisor: Wei-Wen Chang, Ph. D National Taiwan Normal University Taipei, Taiwan June, 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am truly blessed by God to have many knowledgeable, patient, and kind professors guide me during my time in IHRD this lovely and warm institute. My heartfelt thanks first go to my thesis instructor Dr. Wei-Wen Vera Chang. She is the model of how an outstanding teacher can be. Being a junior high school teacher myself, I always take her passion for pursuing knowledge and her sincere care for students as great a example to follow. Also, without help and instruction from my thesis committee members, Dr. Chih-Chien Steven Lai and Dr. Pai-Po Lee, I could hardly make further improvement on this research. Besides being highly knowledgeable, their personal qualities are excellent as they are very empathetic, caring and approachable. For my family, I donate my greatest gratitude to my mother who constantly reminded me to finish this study and provided as much assistance as she could. Sometimes I think of the parenting styles raised by Baumrind in 1966, and I thank God for giving me a pair of good parents adopting the “authoritative style” she mentioned. When my dad and mom discipline me, their attitude is firm, but they are still responsive to my needs without being indulgent. Two years ago, my brother received his master degree while being at work. -

Midpacific Volume47 Issue4.Pdf

PRE-CONFERENCE ISSUE D-PACIFIC OFFICIAL ORGAN OF I HE PANAIOFIEIC UNION /934 it+ t. Featuri '3 C The Third Pan-Pacific Women's Conference By Ann Y. Satterthwaite, Secretory The Melbourne Centenary By Arthur H. O'Connor New Zealand, Land of Geysers and Volcanoes By Dr. Harold T. Stearns e Gorges of the Yangtsze Kiang By Dr. Bolivar Lang Falconer The Philippine Republic By Alexander Hume Ford Vol. XLVII. No. 4. APRIL-JUNE, 1934 25 Cents o Copy ... ai 0.11r filw-liarmr fttga3itr : ,, CONDUCTED BY ALEXANDER HUME FORD A . XLVII. +..s vol. No. 4 . f- g 5 k CONTENTS FOR APRIL-JUNE, 1934 1.1. ..= -i, 17.! k 41' 4; The Third Pan-Pacific Women's Conference - - - - 303 4 By Ann Y. Satterthwaite 4 0 • , 4 - The Sensory Appeal of Sight in Hawaii 311 • By Maurice Hill • 1,.•' • 14 New Zealand, Land of Geysers and Volcanoes - - - 321 • 4,_, By Dr. Harold T. Stearns • (, • i • Mia-Mia to Metropolis, Melbourne Centenary - - - - 327 By Arthur H. O'Connor 14 A Voyage Through the Gorges and Rapids of the • (4.. Yangtsze River 333 st • Ti... By Dr. Bolivar Lang Falconer, F.A.G.S. • $ 4 The Japanese Ideal of Harmony 343 .1 'I By Ken Kawachi 5 .1 i The Philippine Republic 347 .1 By Alexander Hume Ford • .1 Education of Girls in Fiji 349 By A. Maud Griffin al , t Some Impressions of Canada 353 .1 By W. G. Crossle • 1 .1 Scenic Beauty of Korea 359 .10 Index to Volume XLVII (January to June, 1934, inclusive) 364 .1 4 Journal of the Pan-Pacific Research Institution, Vol. -

Ultimate Guide to the World's Best Spirits

ULTIMATE BEVERAGE CHALLENGE 2020 IDENTIFYING THE WORLD’S BEST SPIRITS LIKE NO OTHER COMPETITION The Ultimate Guide to the World’s Best Spirits features the have advanced the entire concept of beverage competitions. highest-scoring results from Ultimate Beverage Challenge’s® The UBC Evaluation Center provides brick-and-mortar proof (UBC) major international beverage competition held in 2020: of UBC’s total commitment to doing things right. It’s the Ultimate Spirits Challenge®. UBC way, where shortcuts are never allowed.” Why has UBC become the beverage industry’s most To get the most accurate results it takes seasoned trusted and respected evaluation company? Answers UBC’s veterans on the judging and preparation teams, the ideal Judging Chairman and Co-Founder F. Paul Pacult, “Three analytical environment, and the most up-to-date methodology. If crucial factors have made UBC the world’s foremost authority on these reasons aren’t enough for you to believe in UBC as being the beverage alcohol quality. world’s finest beverage competition company, visit the UBC website “First is our rigorous, innovative methodology that creates a level for more information at ultimate-beverage.com. playing field for every product entered into USC. This includes a At Ultimate Spirits Challenge® (USC) the quality rankings unique multi-level evaluation system that allows more than one panel for every category for spirits are determined with uncommon skill to analyze each entry, entries served at optimum temperatures, and and precision by all-star Ultimate Spirits Challenge judging panels staging only small flights of 2 to 8 beverages so the judges remain convened by USC Judging Director F. -

2014 Food Processing Ingredients Taiwan

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 12/19/2014 GAIN Report Number: TW14047 Taiwan Food Processing Ingredients 2014 Approved By: Mark Ford Prepared By: Cindy Chang Report Highlights: Even though Taiwan’s food processing and ingredients industries are extremely competitive, there are still great opportunities for U.S. exporters. U.S. exports of high-value food products to Taiwan reached US$1.3 billion in 2014, and this trend is expected to continue for the next several years. Imports of premium food items from other countries has been increasing, but U.S. products continue to be well- accepted by Taiwan consumers due to competitive prices and consumer confidence in the quality and safety of U.S. food products. Taiwan is the United States’ seventh largest agricultural export market due in part to the great success in the food processing and ingredients sector. SECTION I. MARKET SUMMARY Taiwan Food Processing and Ingredients Sector Overview and Trends Opportunities exist to expand U.S. food product sales to Taiwan’s food processing and ingredient sector. Given Taiwan’s current size and population, the country will continue the trend of looking overseas for food processing and ingredients. In 2013, Taiwan’s agricultural industry accounts for less than 2% of GDP and only 5% of employment in Taiwan. Taiwan’s food processing and ingredients industry is comprised of the following major sectors: beverage, coffee/cocoa, condiments/seasonings, dairy products, fats/oils, flour/ bakery products, fruits/vegetables, meat/poultry products, snack foods, and sugar and confectionery.