The Political Ramifications of Hitler's Cult of Wagner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Reviving Hitler's Favorite Music

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 9, Number 35, September 14, 1982 Reviving Hitler's favorite music In Seattle, the Weyerhaeuserfamily is promoting Wagner's Ring cycle as a wedgefor the "new dark age" within the U.S. , writes Mark Calney If you want to see true Wagner you must go to Seattle. greeted not by the presence of our local Northwestpatricians -Winifred Wagner in black tie, which one would expect during the German cycle, but rather the flannel shirt and denim set. There were It was precisely 106 years ago in the ancient Bavarian forest cowboys from Colorado, gays from San Francisco, the on the outskirts of the German village of Bayreuth, that the neighborhood Anglican priest, and what appeared to be the first complete cycle of Richard Wagner's The Ring of the entire anthropology department from the local university, Nibelungs was performed. It was a most regal affair. This dispersed among the crowd. I overheard conversations in was to be the unveiling of mankind's greatest artistic achieve Japanese, German, Spanish, and Texan. A number of these ment, a four-day epic opera concerning the mythical birth pilgrims came from around the world-from Switzerland, and destiny of Man, depicting his various struggles amidst a South Africa, Tasmania, Chile, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia flotsamof dragons, dwarfs, and gods. Who was to attend this from 25 different countriesand from every state in the union. festival heralding the "New Age" in Wagner's "democratic For some it was their eighth sojournto this idyllically under theater?" populated part of America, to participate in the revelries of The premier day of Das Rheingold found the Bayreuth the only festival in the world which contiguously performs theater stuffed to the rafters with every imaginable repre the German and English cycles of the Ring (14 days), and sentative of the European oligarchy from Genoa to St. -

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner's Opera Cycle

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner’s Opera Cycle John Louis DiGaetani Professor Department of English and Freshman Composition James Morris as Wotan in Wagner’s Die Walküre. Photo: Jennifer Carle/The Metropolitan Opera hirty years ago I edited a book in the 1970s, the problem was finding a admirer of Hitler and she turned the titled Penetrating Wagner’s Ring: performance of the Ring, but now the summer festival into a Nazi showplace An Anthology. Today, I find problem is finding a ticket. Often these in the 1930s and until 1944 when the myself editing a book titled Ring cycles — the four operas done festival was closed. But her sons, Inside the Ring: Essays on within a week, as Wagner wanted — are Wieland and Wolfgang, managed to T Wagner’s Opera Cycle — to be sold out a year in advance of the begin- reopen the festival in 1951; there, published by McFarland Press in spring ning of the performances, so there is Wieland and Wolfgang’s revolutionary 2006. Is the Ring still an appropriate clearly an increasing demand for tickets new approaches to staging the Ring and subject for today’s audiences? Absolutely. as more and more people become fasci- the other Wagner operas helped to In fact, more than ever. The four operas nated by the Ring cycle. revive audience interest and see that comprise the Ring cycle — Das Wagnerian opera in a new visual style Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Political Complications and without its previous political associ- Götterdämmerung — have become more ations. Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner and more popular since the 1970s. -

German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “Germany on Their Minds”? German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Anne Clara Schenderlein Committee in charge: Professor Frank Biess, Co-Chair Professor Deborah Hertz, Co-Chair Professor Luis Alvarez Professor Hasia Diner Professor Amelia Glaser Professor Patrick H. Patterson 2014 Copyright Anne Clara Schenderlein, 2014 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Anne Clara Schenderlein is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically. _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii Dedication To my Mother and the Memory of my Father iv Table of Contents Signature Page ..................................................................................................................iii Dedication ..........................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................v -

Wagner in Comix and 'Toons

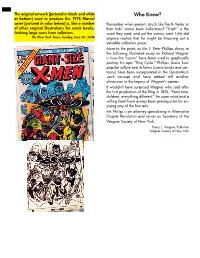

- The original artwork [pictured in black and white Who Knew? at bottom] used to produce the 1975 Marvel cover [pictured in color below] is, like a number Remember when parents struck like Darth Vader at of other original illustrations for comic books, their kids’ comic book collections? “Trash” is the fetching large sums from collectors. word they used, and out the comics went. Little did The New York Times, Sunday, June 30, 2008 anyone realize that he might be throwing out a valuable collectors piece. More to the point, as Mr. F. Peter Phillips shows in the following illustrated essay on Richard Wagner is how the “comix” have been used to graphically portray his epic “Rng Cycle.” Phillips shows how popular culture and its forms (comic books and car- toons) have been incorporated in the Gesamtkust- werk concept and have added still another dimension to the legacy of Wagner’s operas. It wouldn’t have surprised Wagner who said after the first production of the Ring in 1876, “Next time, children, everything different.” An open mind and a willing heart have always been prerequisites for en- joying any of the fine arts. Mr. Phllips is an attorney specializing in Alternative Dispute Resolution and serves as Secretary of the Wagner Society of New York. Harry L. Wagner, Publisher Wagner Society of New York Wagner in Comix and ‘Toons By F. Peter Phillips Recent publications have revealed an aspect of Wagner-inspired literature that has been grossly overlooked—Wagner in graphic art (i.e., comics) and in animated cartoons. The Ring has been ren- dered into comics of substantial integrity at least three times in the past two decades, and a recent scholarly study of music used in animated cartoons has noted uses of Wagner’s music that suggest that Wagner’s influence may even more profoundly im- bued in our culture than we might have thought. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

Zur Kontinuität Des Groß- Und Weltmachtstrebens Der Deutschen Marineführung

Dokumentation Gerhard Schreiber Zur Kontinuität des Groß- und Weltmachtstrebens der deutschen Marineführung Kontinuität als geschichtswissenschaftliche Kategorie fragt zum einen, ob und wann ein historisches Kontinuum möglich ist, und sie beschreibt zum anderen — allgemein gesehen — eine geschichtliche Einheit, die auf der weitgehenden Identität der Mo- mente beruht, die in einem zeitlichen Längsschnitt zueinander in Beziehung gesetzt werden. Mit Kontinuität ist somit weder Kausalität noch Determiniertheit der histori- schen Entwicklung gemeint, sondern die Ähnlichkeit und die Erklärbarkeit des Späte- ren mit dem Früheren1. Mit einem derartigen Vorverständnis stellt die vorliegende Dokumentation die Frage nach der Sichselbstgleichheit der Machtpolitik im preußisch-deutschen Nationalstaat, dem Deutschen Reich zwischen 1871 und dem Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges2. Das eigentliche Untersuchungsfeld soll dabei — quasi idealtypisch — auf eine konservative Führungselite, die Marineführung3, eingeengt werden. Zur Diskussion steht die These, daß es zwischen den imperialistischen Zielsetzungen der Marine, wie sie späte- stens mit dem Beginn des Großflottenbaus zutage traten, und den Überlegungen zu einer deutschen Weltvorherrschaft, die im Dritten Reich in diesem Wehrmachtteil an- gestellt wurden, eine ungebrochene machtpolitische Kontinuität gab. Die dem spezifi- schen Denksystem der Marineführung immanente ideologische Kohärenz konkreti- sierte sich in diesem Zusammenhang vor 1918, vor 1933 und bis 1945 in der einem ri- gorosen Navalismus oder -

Simon O'neill ONZM

Simon O’Neill ONZM Tenor “Simon O'Neill made a tremendous debut in the title-role, giving notice that he is the best heroic tenor to emerge over the last decade.” Rupert Christiansen, The Telegraph, UK. A native of New Zealand, Simon O’Neill is one of the finest helden-tenors on the international stage. He has frequently performed with the Metropolitan Opera, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Berlin, Hamburg and Bayerische Staatsopern, Teatro alla Scala and the Bayreuth, Salzburg, Edinburgh and BBC Proms Festivals, appearing with a number of illustrious conductors including Daniel Barenboim, Sir Simon Rattle, James Levine, Riccardo Muti, Valery Gergiev, Sir Antonio Pappano, Pietari Inkinen, Pierre Boulez, Sir Mark Elder, Sir Colin Davis, Simone Young, Edo de Waart, Fabio Luisi, Donald Runnicles, Sir Simon Rattle, Jaap Van Zweden and Christian Thielemann. Simon’s performances as Siegmund in Die Walküre at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden with Pappano, Teatro alla Scala and Berlin Staatsoper with Barenboim, at the Metropolitan Opera with Runnicles in the celebrated Otto Schenk production returning with Luisi in the Lepage Ring Cycle and in the Götz Friedrich production at Deutsche Oper Berlin with Rattle were performed to wide critical acclaim. He was described in the international press as "an exemplary Siegmund, terrific of voice", "THE Wagnerian tenor of his generation" and "a turbo-charged tenor". During this season’s engagements Simon makes his debut at: Tanglewood with the Boston Symphony and Andris Nelsons and the Toronto Symphony with Sir Andrew Davis and Orquestra de la Comunitat Valenciana with Henrik Nánási as Siegmund in concert performances of Die Walküre. -

ARSC Journal, Vol.21, No

Sound Recording Reviews Wagner: Parsifal (excerpts). Berlin State Opera Chorus and Orchestra (a) Bayreuth Festival Chorus and Orchestra (b), cond. Karl Muck. Opal 837/8 (LP; mono). Prelude (a: December 11, 1927); Act 1-Transformation & Grail Scenes (b: July/ August, 1927); Act 2-Flower Maidens' Scene (b: July/August, 1927); Act 3 (a: with G. Pistor, C. Bronsgeest, L. Hofmann; slightly abridged; October 10-11and13-14, 1928). Karl Muck conducted Parsifal at every Bayreuth Festival from 1901 to 1930. His immediate predecessor was Franz Fischer, the Munich conductor who had alternated with Hermann Levi during the premiere season of 1882 under Wagner's own supervi sion. And Muck's retirement, soon after Cosima and Siegfried Wagner died, brought another changing of the guard; Wilhelm Furtwangler came to the Green Hill for the next festival, at which Parsifal was controversially assigned to Arturo Toscanini. It is difficult if not impossible to tell how far Muck's interpretation of Parsifal reflected traditions originating with Wagner himself. Muck's act-by-act timings from 1901 mostly fall within the range defined in 1882 by Levi and Fischer, but Act 1 was decidedly slower-1:56, compared with Levi's 1:47 and Fischer's 1:50. Muck's timing is closer to that of Felix Mottl, who had been a musical assistant in 1882, and of Hans Knappertsbusch in his first and slowest Bayreuth Parsifal. But in later summers Muck speeded up to the more "normal" timings of 1:50 and 1:47, and the extensive recordings he made in 1927-8, now republished by Opal, show that he could be not only "sehr langsam" but also "bewegt," according to the score's requirements. -

From Page to Stage: Wagner As Regisseur

Wagner Ia 5/27/09 3:55 PM Page 3 Copyrighted Material From Page to Stage: Wagner as Regisseur KATHERINE SYER Nowadays we tend to think of Richard Wagner as an opera composer whose ambitions and versatility extended beyond those of most musicians. From the beginning of his career he assumed the role of his own librettist, and he gradually expanded his sphere of involvement to include virtually all aspects of bringing an opera to the stage. If we focus our attention on the detailed dramatic scenarios he created as the bases for his stage works, we might well consider Wagner as a librettist whose ambitions extended rather unusually to the area of composition. In this light, Wagner could be considered alongside other theater poets who paid close attention to pro- duction matters, and often musical issues as well.1 The work of one such figure, Eugène Scribe, formed the foundation of grand opera as it flour- ished in Paris in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Wagner arrived in this operatic epicenter in the fall of 1839 with work on his grand opera Rienzi already under way, but his prospects at the Opéra soon waned. The following spring, Wagner sent Scribe a dramatic scenario for a shorter work hoping that the efforts of this famous librettist would help pave his way to success. Scribe did not oblige. Wagner eventually sold the scenario to the Opéra, but not before transforming it into a markedly imaginative libretto for his own use.2 Wagner’s experience of operatic stage produc- tion in Paris is reflected in many aspects of the libretto of Der fliegende Holländer, the beginning of an artistic vision that would draw him increas- ingly deeper into the world of stage direction and production. -

Wagner) Vortrag Am 21

Miriam Drewes Die Bühne als Ort der Utopie (Wagner) Vortrag am 21. August 2013 im Rahmen der „Festspiel-Dialoge“ der Salzburger Festspiele 2013 Anlässlich des 200. Geburtstags von Richard Wagner schreibt Christine Lemke-Matwey in „Der Zeit“: „Keine deutsche Geistesgröße ist so gründlich auserzählt worden, politisch, ästhetisch, in Büchern und auf der Bühne wie der kleine Sachse mit dem Samtbarrett. Und bei keiner fällt es so schwer, es zu lassen.“1 Allein zum 200. Geburtstag sind an die 3500 gedruckte Seiten Neuinterpretation zu Wagners Werk und Person entstanden. Ihre Bandbreite reicht vom Bericht biographischer Neuentdeckungen, über psychologische Interpretationen bis hin zur Wiederauflage längst überholter Aspekte in Werk und Wirkung. Inzwischen hat die Publizistik eine Stufe erreicht, die sich von Wagner entfernend vor allen Dingen auf die Rezeption von Werk und Schöpfer richtet und dabei mit durchaus ambivalenten Lesarten aufwartet. Begegnet man, wie der Musikwissenschaftler Wolfgang Rathert konzediert, Person und Werk naiv, begibt man sich alsbald auf vermintes ideologisches Terrain,2 auch wenn die Polemiken von Wagnerianern und Anti-Wagnerianern inzwischen nicht mehr gar so vehement und emphatisch ausfallen wie noch vor 100 oder 50 Jahren. Selbst die akademische Forschung hat hier, Rathert zufolge, nur wenig ausrichten können. Immerhin aber zeigt sie eines: die Beschäftigung mit Wagner ist nicht obsolet, im Gegenteil, die bis ins Ideologische reichende Rezeption führe uns die Ursache einer heute noch ausgesprochenen Produktivität vor Augen – sowohl diskursiv als auch auf die Bühne bezogen. Ich möchte mich in diesem Vortrag weniger auf diese neuesten Ergebnisse oder Pseudoergebnisse konzentrieren, als vielmehr darauf, in wieweit der Gedanke des Utopischen, der Richard Wagners theoretische Konzeption wie seine Opernkompositionen durchdringt, konturiert ist. -

Was Hitler a Darwinian?

Was Hitler a Darwinian? Robert J. Richards The University of Chicago The Darwinian underpinnings of Nazi racial ideology are patently obvious. Hitler's chapter on "Nation and Race" in Mein Kampf discusses the racial struggle for existence in clear Darwinian terms. Richard Weikart, Historian, Cal. State, Stanislaus1 Hamlet: Do you see yonder cloud that's almost in shape of a camel? Shakespeare, Hamlet, III, 2. 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Issues regarding a Supposed Conceptually Causal Connection . 4 3. Darwinian Theory and Racial Hierarchy . 10 4. The Racial Ideology of Gobineau and Chamberlain . 16 5. Chamberlain and Hitler . 27 6. Mein Kampf . 29 7. Struggle for Existence . 37 8. The Political Sources of Hitler’s Anti-Semitism . 41 9. Ethics and Social Darwinism . 44 10. Was the Biological Community under Hitler Darwinian? . 46 11. Conclusion . 52 1. Introduction Several scholars and many religiously conservative thinkers have recently charged that Hitler’s ideas about race and racial struggle derived from the theories of Charles Darwin (1809-1882), either directly or through intermediate sources. So, for example, the historian Richard Weikart, in his book From Darwin to Hitler (2004), maintains: “No matter how crooked the road was from Darwin to Hitler, clearly Darwinism and eugenics smoothed the path for Nazi ideology, especially for the Nazi 1 Richard Weikart, “Was It Immoral for "Expelled" to Connect Darwinism and Nazi Racism?” (http://www.discovery.org/a/5069.) 1 stress on expansion, war, racial struggle, and racial extermination.”2 In a subsequent book, Hitler’s Ethic: The Nazi Pursuit of Evolutionary Progress (2009), Weikart argues that Darwin’s “evolutionary ethics drove him [Hitler] to engage in behavior that the rest of us consider abominable.”3 Other critics have also attempted to forge a strong link between Darwin’s theory and Hitler’s biological notions.