The Nuremberg Party Rallies, Wagner, and the Theatricality of Hitler And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Beyond the Boat

Beyond the Boat RIVER CRUISE EXTENSION TOURS Welcome! We know the gift of travel is a valuable experience that connects people and places in many special ways. When tourism closed its doors during the difficult months of the COVID-19 outbreak, Germany ranked as the second safest country in the world by the London Deep Knowled- ge Group, furthering its trust as a destination. When you are ready to explore, river cruises continue to be a great way of traveling around Germany and this handy brochure provides tour ideas for those looking to venture beyond the boat or plan a stand-alone dream trip to Bavaria. The special tips inside capture the spirit of Bavaria – traditio- nally different and full of surprises. Safe travel planning! bavaria.by/rivercruise facebook.com/visitbavaria instagram.com/bayern Post your Bavarian experiences at #visitbavaria. Feel free to contact our US-based Bavaria expert Diana Gonzalez: [email protected] TIP: Stay up to date with our trade newsletter. Register at: bavaria.by/newsletter Publisher: Photos: p. 1: istock – bkindler | p. 2: BayTM – Peter von Felbert, Gert Krautbauer | p. 3: BayTM – Peter von Felbert, fotolia – BAYERN TOURISMUS herculaneum79 | p. 4/5: BayTM – Peter von Felbert | p. 6: BayTM – Gert Krautbauer | p. 7: BayTM – Peter von Felbert, Gert Kraut- Marketing GmbH bauer (2), Gregor Lengler, Florian Trykowski (2), Burg Rabenstein | p. 8: BayTM – Gert Krautbauer | p. 9: FC Bayern München, Arabellastr. 17 Burg Rabenstein, fotolia – atira | p. 10: BayTM – Peter von Felbert | p. 11: Käthe Wohlfahrt | p. 12: BayTM – Jan Greune, Gert Kraut- 81925 Munich, Germany bauer | p. -

Business Bavaria Newsletter

Business Bavaria Newsletter Issue 07/08 | 2013 What’s inside 5 minutes with … Elissa Lee, Managing Director of GE Aviation, Germany Page 2 In focus: Success of vocational training Page 3 Bavaria in your Briefcase: Summer Architecture award for tourism edition Page 4 July/August 2013 incl. regional special Upper Franconia Apprenticeships – a growth market Bavaria’s schools are known for their well-trained school leavers. In July, a total of According to the latest education monitoring publication of the Initiative Neue 130,000 young Bavarians start their careers. They can choose from a 2% increase Soziale Marktwirtschaft, Bavaria is “top when it comes to school quality and ac- in apprenticeships compared to the previous year. cess to vocational training”. More and more companies are increasing the number of training positions to promote young people and thus lay the foundations for With 133,000 school leavers, 2013 has a sizeable schooled generation. Among long-term success. the leavers are approximately 90,000 young people who attended comprehensive school for nine years or grammar school for ten. Following their vocational train- The most popular professions among men and women are very different in Ba- ing, they often start their apprenticeships right away. varia: while many male leavers favour training as motor or industrial mechanics To ensure candidates and positions are properly matched, applicants and com- or retail merchants, occupations such as office manager, medical specialist and panies seeking apprentices are supported in their search by the Employment retail expert are the most popular choices among women. Agency. Between October 2012 and June 2013 companies made a total of 88,541 free, professional, training places available – an increase of 1.8% on the previ- www.ausbildungsoffensive-bayern.de ous year. -

Reviving Hitler's Favorite Music

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 9, Number 35, September 14, 1982 Reviving Hitler's favorite music In Seattle, the Weyerhaeuserfamily is promoting Wagner's Ring cycle as a wedgefor the "new dark age" within the U.S. , writes Mark Calney If you want to see true Wagner you must go to Seattle. greeted not by the presence of our local Northwestpatricians -Winifred Wagner in black tie, which one would expect during the German cycle, but rather the flannel shirt and denim set. There were It was precisely 106 years ago in the ancient Bavarian forest cowboys from Colorado, gays from San Francisco, the on the outskirts of the German village of Bayreuth, that the neighborhood Anglican priest, and what appeared to be the first complete cycle of Richard Wagner's The Ring of the entire anthropology department from the local university, Nibelungs was performed. It was a most regal affair. This dispersed among the crowd. I overheard conversations in was to be the unveiling of mankind's greatest artistic achieve Japanese, German, Spanish, and Texan. A number of these ment, a four-day epic opera concerning the mythical birth pilgrims came from around the world-from Switzerland, and destiny of Man, depicting his various struggles amidst a South Africa, Tasmania, Chile, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia flotsamof dragons, dwarfs, and gods. Who was to attend this from 25 different countriesand from every state in the union. festival heralding the "New Age" in Wagner's "democratic For some it was their eighth sojournto this idyllically under theater?" populated part of America, to participate in the revelries of The premier day of Das Rheingold found the Bayreuth the only festival in the world which contiguously performs theater stuffed to the rafters with every imaginable repre the German and English cycles of the Ring (14 days), and sentative of the European oligarchy from Genoa to St. -

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner's Opera Cycle

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner’s Opera Cycle John Louis DiGaetani Professor Department of English and Freshman Composition James Morris as Wotan in Wagner’s Die Walküre. Photo: Jennifer Carle/The Metropolitan Opera hirty years ago I edited a book in the 1970s, the problem was finding a admirer of Hitler and she turned the titled Penetrating Wagner’s Ring: performance of the Ring, but now the summer festival into a Nazi showplace An Anthology. Today, I find problem is finding a ticket. Often these in the 1930s and until 1944 when the myself editing a book titled Ring cycles — the four operas done festival was closed. But her sons, Inside the Ring: Essays on within a week, as Wagner wanted — are Wieland and Wolfgang, managed to T Wagner’s Opera Cycle — to be sold out a year in advance of the begin- reopen the festival in 1951; there, published by McFarland Press in spring ning of the performances, so there is Wieland and Wolfgang’s revolutionary 2006. Is the Ring still an appropriate clearly an increasing demand for tickets new approaches to staging the Ring and subject for today’s audiences? Absolutely. as more and more people become fasci- the other Wagner operas helped to In fact, more than ever. The four operas nated by the Ring cycle. revive audience interest and see that comprise the Ring cycle — Das Wagnerian opera in a new visual style Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Political Complications and without its previous political associ- Götterdämmerung — have become more ations. Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner and more popular since the 1970s. -

Radfahren Im Ferienland MAIN-SPESSART - Eine Runde Sache

Radfahren im Ferienland MAIN-SPESSART - eine runde Sache DIE SCHÖNSTEN FESTE Was früher die Wanderschuhe waren, ist heute der Drahtesel: Zwei Drittel aller Camper bringen ihre WEITERE TOURISTISCHE IM MAIN-SPESSART-RAUM HIGHLIGHTS Im Landkreis Main Spessart lässt Fahrräder mit. Im Main-Spessart finden sie beste Voraussetzungen für unvergessliche Touren sich sehr gut feiern. Zahlreiche Nur schwer lassen sich aus der Wein- und Bierfeste der örtlichen Der Main mit seinem markanten „Bayernnetz für Radler“ als Grund- 118 km von Gemünden am Main aufzuwuchten, besucht das Ehe- Vielzahl touristischer Attrak-tio- Vereine sowie sonstige Veran- Lauf in Ost–West–Richtung, die gerüst, zusammen mit den über 1000 bis nach Mellrichstadt vor den Ost- paar lieber die zahlreichen Stadt- nen ein paar wenige herausfil- staltungen machen die Auswahl Lebensader des Frankenlandes, und km regionalen und örtlichen Rad- hängen der Rhön den Anschluss und Weinfeste der Region. Gewiss tern. Zu reich ist die Region schwer. Hier die schönsten Feste der Spessart, das größte zusammen- wegen, ein attraktives, abwechs- an den Main-Werra-Radwanderweg ein weiterer Pluspunkt für MAIN- MAIN-SPESSART auch in dieser zwischen Juni und September: hängende Laubwaldgebiet Deutsch- lungsreiches, über 1300 km langes her. Varianten mit dem regionalen SPESSART: Inmitten von Fachwerk- Hinsicht. Starten wir den Ver- lands, sind die Namengeber des Radwegenetz. Durch gute Zug- und Radwegenetz bieten unvergessliche häusern den süffigen Schoppenwein such ohne den Anspruch auf Von Lohr bis Laurenzi Landkreises MAIN-SPESSART. Schiffsverbindungen bietet sich Naturerlebnisse. Der Kahltal-Spes- trinken und die lockere Atmosphäre Vollständigkeit mit dem 1200 Bereits ab April / Mai, wenn in zudem die Möglichkeit auch Teil- sart-Radwanderweg öffnet ab Lohr der Feste genießen, während das Jahre alten Weinort Homburg, Im Juni der „Karschter Mee den Laubwäldern die jungen Blätter strecken problemlos zu meistern. -

Bayreuth, Germany

BAYREUTH SITE Bayreuth, Germany Weiherstr. 40 95448 Bayreuth 153 hectares employees & 6,3 Germany site footprint Tel.: +49 921 80 70 contractors ABOUT THE SITE ABOUT LYONDELLBASELL The Bayreuth Site is located in northern Bavaria, Germany and is one of LyondellBasell’s largest PP LyondellBasell (NYSE: LYB) is one of the largest compounding plants. The plant produces a complex portfolio of about 375 different grades composed of up to 25 different ingredients for automotive customers in Central Europe. The site manufactures plastics, chemicals and refining companies grades in a wide range of colors according to customer demand. The site features eight extrusion lines in the world. Driven by its 13,000 employees and an onsite Technical Center for product and application development. Recent capacity increases around the globe, LyondellBasell produces were performed in the years 2013 and 2016. materials and products that are key to advancing solutions to modern challenges ECONOMIC IMPACT like enhancing food safety through lightweight and flexible packaging, protecting the purity Estimate includes yearly total for goods & services purchased and employee of water supplies through stronger and more million $33.4 pay and benefits, excluding raw materials purchased (basis 2016) versatile pipes, and improving the safety, comfort and fuel efficiency of many of the cars and trucks on the road. LyondellBasell COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT sells products into approximately 100 countries LyondellBasell takes great pride in the communities we represent. Our Bayreuth operation supports and is the world’s largest licensor of polyolefin the Bavaria community by donating a gift to school children that goes toward traffic safety education. -

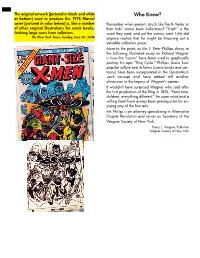

Wagner in Comix and 'Toons

- The original artwork [pictured in black and white Who Knew? at bottom] used to produce the 1975 Marvel cover [pictured in color below] is, like a number Remember when parents struck like Darth Vader at of other original illustrations for comic books, their kids’ comic book collections? “Trash” is the fetching large sums from collectors. word they used, and out the comics went. Little did The New York Times, Sunday, June 30, 2008 anyone realize that he might be throwing out a valuable collectors piece. More to the point, as Mr. F. Peter Phillips shows in the following illustrated essay on Richard Wagner is how the “comix” have been used to graphically portray his epic “Rng Cycle.” Phillips shows how popular culture and its forms (comic books and car- toons) have been incorporated in the Gesamtkust- werk concept and have added still another dimension to the legacy of Wagner’s operas. It wouldn’t have surprised Wagner who said after the first production of the Ring in 1876, “Next time, children, everything different.” An open mind and a willing heart have always been prerequisites for en- joying any of the fine arts. Mr. Phllips is an attorney specializing in Alternative Dispute Resolution and serves as Secretary of the Wagner Society of New York. Harry L. Wagner, Publisher Wagner Society of New York Wagner in Comix and ‘Toons By F. Peter Phillips Recent publications have revealed an aspect of Wagner-inspired literature that has been grossly overlooked—Wagner in graphic art (i.e., comics) and in animated cartoons. The Ring has been ren- dered into comics of substantial integrity at least three times in the past two decades, and a recent scholarly study of music used in animated cartoons has noted uses of Wagner’s music that suggest that Wagner’s influence may even more profoundly im- bued in our culture than we might have thought. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

Global Change Ecology (M.Sc.)

UNIVERSITY OF BAYREUTH Graduate Program (M.Sc.) UNIVERSITY OF AUGSBURG UNIVERSITY OF WÜRZBURG Global Change Ecology Scope Structure The graduate program Global Change Ecology is devoted The general structure of the program (120 ECTS) brings to understanding and analyzing the most important and together natural sciences (research in global change and eco- consequential environmental concern of the 21st century: logy - 70 %) and social sciences (laws and regulations, social Environmental Global Change. Problems of an entirely new and dimensions, socio-economic implications - 30%). The obtained Change interdisciplinary nature require the establishment of degree is a Master of Science. Based on additional research ac- Universität innovative approaches in research and education. tivity, a PhD degree can be obtained. Methods Augsburg Ecological A special program focus is the linking of natural science The courses in the graduate program require a high Change perspectives on global change with approaches in social level of performance. Students are selected via a standar- Universität science disciplines. dized aptitude assessment procedure that meets the highest Internship/ Schools Würzburg international criteria. Bachelor degrees related to all fields of The elite study program combines the expertise of the Uni- environmental science will provide for acceptance to the pro- Societal versities of Bayreuth, Augsburg and Würzburg, with that gram. Finally, a select number of students will be accepted who Change of Bavarian and international research institutions, as well as may profit from excellent infrastructure and direct one-on-one Master Thesis economic, administrative and international organizations. communication with their supervisors. The program is unique in Germany, from the standpoint of content, and at the forefront with respect to international efforts. -

Was Hitler a Darwinian?

Was Hitler a Darwinian? Robert J. Richards The University of Chicago The Darwinian underpinnings of Nazi racial ideology are patently obvious. Hitler's chapter on "Nation and Race" in Mein Kampf discusses the racial struggle for existence in clear Darwinian terms. Richard Weikart, Historian, Cal. State, Stanislaus1 Hamlet: Do you see yonder cloud that's almost in shape of a camel? Shakespeare, Hamlet, III, 2. 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Issues regarding a Supposed Conceptually Causal Connection . 4 3. Darwinian Theory and Racial Hierarchy . 10 4. The Racial Ideology of Gobineau and Chamberlain . 16 5. Chamberlain and Hitler . 27 6. Mein Kampf . 29 7. Struggle for Existence . 37 8. The Political Sources of Hitler’s Anti-Semitism . 41 9. Ethics and Social Darwinism . 44 10. Was the Biological Community under Hitler Darwinian? . 46 11. Conclusion . 52 1. Introduction Several scholars and many religiously conservative thinkers have recently charged that Hitler’s ideas about race and racial struggle derived from the theories of Charles Darwin (1809-1882), either directly or through intermediate sources. So, for example, the historian Richard Weikart, in his book From Darwin to Hitler (2004), maintains: “No matter how crooked the road was from Darwin to Hitler, clearly Darwinism and eugenics smoothed the path for Nazi ideology, especially for the Nazi 1 Richard Weikart, “Was It Immoral for "Expelled" to Connect Darwinism and Nazi Racism?” (http://www.discovery.org/a/5069.) 1 stress on expansion, war, racial struggle, and racial extermination.”2 In a subsequent book, Hitler’s Ethic: The Nazi Pursuit of Evolutionary Progress (2009), Weikart argues that Darwin’s “evolutionary ethics drove him [Hitler] to engage in behavior that the rest of us consider abominable.”3 Other critics have also attempted to forge a strong link between Darwin’s theory and Hitler’s biological notions. -

Accidental Tourism in Wagner's Bayreuth

1 Accidental Tourism in Wagner’s Bayreuth An Analysis of Visitors’ Motivations and Experiences in Wagner’s Bayreuth. Myrto Moraitou Master Thesis Dissertation Accidental Tourism in Wagner’s Bayreuth An analysis of visitors’ motivations and experiences in Wagner’s Bayreuth Master Thesis Name: Myrto Moraitou Student number: 433480 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. S. L. Reijnders Date: June 12th 2018 Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Arts, Culture and Society Erasmus University Rotterdam Accidental Tourism in Wagner’s Bayreuth An analysis of visitors’ motivations and experiences in Wagner’s Bayreuth Abstract This research offers an analysis of the motivations and experiences of visitors in Wagner’s Bayreuth. Wagner’s Bayreuth is a great example of music tourism as it is maybe the first site where music lovers from around the world visited in order to listen and experience classical music. Taking as a starting point the theories developed on music tourism studies on sites related to popular music such as the ones of Connell and Gibson (2003), Gibson and Connell (2005, 2007) and Bolderman and Reijnders (2016), this research will try to identify whether these theories apply also on the classical music field, based on the example of Wagner’s Bayreuth. This paper addresses four visitor elements; the motivation, the expectation, the experience and evaluation of the above. The personal ‘identity’ of each visitor plays also an important role on their motives and evaluation procedure of the experience, as it defines the relationship between the visitor and the place and also the way of evaluation through their personal story. Through the analysis of these elements, using a qualitative approach with in depth interviews based on these elements, the findings suggest that there are some similarities in the behavior of the visitors between Wagner’s Bayreuth and previous researches on popular culture sites.