Recreation, Tourism and Nature in a Changing World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neal Addresses NHS Class by THOMAS MATTSON TRIBUNE STAFF WRITER NORTHBRIDGE — U.S

Mailed free to requesting homes in Douglas, Northbridge and Uxbridge Vol. III, No. 17 Complimentary to homes by request ONLINE: www.blackstonevalleytribune.com “Honesty is the first chapter in the book of wisdom.” Friday, January 22, Neal addresses NHS class BY THOMAS MATTSON TRIBUNE STAFF WRITER NORTHBRIDGE — U.S. Rep. Richard Neal, D-Massachusetts, spoke on a variety of subjects Thursday, Jan. 14, and then answered questions from students at Northbridge High School. Neal noted every bill goes through the House Ways and Means Committee, of which he is a member. He said there are 20 Democrats and 16 Republicans on that committee. He noted the group deals with taxes, tariffs, trade, Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and welfare. He said he had worked for educa- tion, health care and manufactur- ing jobs in Massachusetts. “Every tax bill goes through my committee,” Neal said. He noted the importance of growing the economy but also of meeting responsibilities. “We find ourselves in an eco- nomic morass,” he declared of the country. Neal spoke of picking up and going forward, with one slight caveat. He would do that without entering a partisan fray, “but if it becomes a matter of demagoguery (from the other side), I’ll get into it.” By that, the congressman seemed to mean he would not sit Thomas Mattson photo idly by if conservatives attack Congressman Richard Neal (left) with NHS senior James Tabur. Neal nominated Tabur every attempt of Democrats in to receive an appointment at a U.S. military academy. Congress to achieve things. Courtesy photo “It’s entertainment versus infor- acknowledged, “but we also gov- People see something and say Nick Hollibaugh at work on a sculpture in his Manchaug Mills studio. -

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine Index of Reviews

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine Index of Reviews All reviews of flatpicking CDs, DVDs, Videos, Books, Guitar Gear and Accessories, Guitars, and books that have appeared in Flatpicking Guitar Magazine are shown in this index. CDs (Listed Alphabetically by artists last name - except for European Gypsy Jazz CD reviews, which can all be found in Volume 6, Number 3, starting on page 72): Brandon Adams, Hardest Kind of Memories, Volume 12, Number 3, page 68 Dale Adkins (with Tacoma), Out of the Blue, Volume 1, Number 2, page 59 Dale Adkins (with Front Line), Mansions of Kings, Volume 7, Number 2, page 80 Steve Alexander, Acoustic Flatpick Guitar, Volume 12, Number 4, page 69 Travis Alltop, Two Different Worlds, Volume 3, Number 2, page 61 Matthew Arcara, Matthew Arcara, Volume 7, Number 2, page 74 Jef Autry, Bluegrass ‘98, Volume 2, Number 6, page 63 Jeff Autry, Foothills, Volume 3, Number 4, page 65 Butch Baldassari, New Classics for Bluegrass Mandolin, Volume 3, Number 3, page 67 William Bay: Acoustic Guitar Portraits, Volume 15, Number 6, page 65 Richard Bennett, Walking Down the Line, Volume 2, Number 2, page 58 Richard Bennett, A Long Lonesome Time, Volume 3, Number 2, page 64 Richard Bennett (with Auldridge and Gaudreau), This Old Town, Volume 4, Number 4, page 70 Richard Bennett (with Auldridge and Gaudreau), Blue Lonesome Wind, Volume 5, Number 6, page 75 Gonzalo Bergara, Portena Soledad, Volume 13, Number 2, page 67 Greg Blake with Jeff Scroggins & Colorado, Volume 17, Number 2, page 58 Norman Blake (with Tut Taylor), Flatpickin’ in the -

Waldeckische Bibliographie“ Im Juni 1998 Gedruckt Wurde (Zu Hochgrebe S

WALDECKISCHE BIBLIOGRAPHIE Bearbeitet von HEINRICH HOCHGREBE 1998 Für die Präsentation im Internet eingerichtet von Dr. Jürgen Römer, 2010. Für die Benutzung ist unbedingt die Vorbemerkung zur Internetpräsentation auf S. 3 zu beachten! 1 EINLEITUNG: Eine Gesamtübersicht über das Schrifttum zu Waldeck und Pyrmont fehlt bisher. Über jährliche Übersichten der veröffentlichten Beiträge verfügen der Waldeckische Landeskalender und die hei- matkundliche Beilage zur WLZ, "Mein Waldeck". Zu den in den Geschichtsblättern für Waldeck u. Pyrmont veröffentlichten Beiträgen sind Übersichten von HERWIG (Gbll Waldeck 28, 1930, S. 118), BAUM (Gbll Waldeck 50, 1958, S. 154) und HOCHGREBE (Gbll Waldeck 76, 1988, S. 137) veröffentlicht worden. NEBELSIECK brachte ein Literaturver-zeichnis zur waldeckischen Kir- chengeschichte (Gbll Waldeck 38, 1938, S. 191). Bei Auswahl der Titel wurden die Grenzgebiete Westfalen, Hessen, Itter, Frankenberg und Fritzlar ebenso berücksichtigt wie die frühen geschichtlichen Beziehungen zu den Bistümern Köln, Mainz, Paderborn sowie der Landgrafschaft Hessen-Kassel. Es war mir wohl bewußt, daß es schwierig ist, hier die richtige Grenze zu finden. Es werden auch Titel von waldeckischen Autoren angezeigt, die keinen Bezug auf Waldeck haben. Die Vornamen der Autoren sind ausgeschrieben, soweit diese sicher feststellbar waren, was jedoch bei älteren Veröffentlichungen nicht immer möglich war. Berücksichtigung fanden Titel aus periodisch erscheinenden Organen, wichtige Artikel aus der Ta- gespresse und selbständige Veröffentlichungen in Buch- oder Broschürenform. Für die Bearbeitung der Lokalgeschichte sind hier zahlreiche Quellen aufgezeigt. Bei Überschneidung, bzw. wenn keine klare Scheidung möglich war, sind die Titel u. U. mehrfach, d. h. unter verschiedenen Sachgebieten aufgeführt. Anmerkungen in [ ] sind vom Bearbeiter einge- fügt worden. Verständlicherweise kann eine solche Zusammenstellung keinen Anspruch auf Vollständigkeit er- heben, sie hätte aber auch außerhalb meiner Möglichkeiten gelegen, was besonders für das ältere Schrifttum zutrifft. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Jerry Garcia from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Jerry Garcia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Background information Birth name Jerome John Garcia Born August 1, 1942, San Francisco, California, United States Died August 9, 1995 (aged 53), Forest Knolls, California, United States Genres Folk rock, bluegrass, progressive rock Occupation(s) Musician, songwriter Instruments Guitar, vocals, pedal steel guitar, banjo Years active 1960–1995 Labels Rhino, Arista, Warner Bros., Acoustic Disc, Grateful Dead Associated acts Grateful Dead, Legion of Mary, Reconstruction, Jerry Garcia Band, Old and in the Way, Jerry Garcia Acoustic Band, New Riders of the Purple Sage͵ Garcia Grisman Band Notable instruments Fender Stratocaster "Alligator" Doug Irwin-modified Alembic "Wolf" Gibson SGs Guild Starfire 1957 Gibson Les Paul Gold-top Les Paul with P-90 Doug Irwin Custom "Tiger" Doug Irwin Custom "Rosebud" Stephen Cripe Custom "Lightning Bolt," Martin D-28, Takamine acoustic-electric guitars Travis Bean TB1000S, TB500[1] Jerome John "Jerry" Garcia (August 1, 1942 – August 9, 1995) was an American musician best known for his lead guitar work, singing and songwriting with the band the Grateful Dead, which came to prominence during the counterculture era. Though he disavowed the role, Garcia was viewed by many as the leader or "spokesman" of the group. One of its founders, Garcia performed with the Grateful Dead for their entire thirty-year career (1965–1995). Garcia also founded and participated in a variety of side projects, including the Saunders-Garcia Band (with longtime friend Merl Saunders), the Jerry Garcia Band, Old and in the Way, the Garcia/Grisman acoustic duo, Legion of Mary, and the New Riders of the Purple Sage (which Garcia co-founded with John Dawson and David Nelson). -

Germany E-Mail: Oea-1000 @ Wp.Gate.Bmu.De Internet: Printed By: Neusser Druckerei Und Verlag Gmbh, Neuss As Of: March 1998

Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety Federal Government Report under the Convention on Biological Diversity National Report on biological Diversity Federal Environment Ministry Imprint Published by: Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety P.O. Box 12 06 29 53048 Bonn Germany E-Mail: oea-1000 @ wp.gate.bmu.de Internet: http://www.bmu.de Printed by: Neusser Druckerei und Verlag GmbH, Neuss As of: March 1998 2 Contents Summary . 7 1. Introduction: The convention on biological diversity: a new way of looking at the conservation and use of biological diversity . 8 2. Background . 10 2.1 Legal and political framework in Germany for compiling the National Report and the national strategy . 10 2.1.1 Participation of political levels, social groups and institutions in the compilation of the National Report . 10 2.1.2 Responsibilities for implementing the national strategy . 11 2.1.3 Links with European activities . 12 2.2 Brief summary of Germany's geographical, ecological and economic situation, existing biological diversity and the institutional and legal framework . 13 2.2.1 Germany's geographical and ecological situation . 13 2.2.2 Germany's economic situation . 13 2.2.3 Existing status of biological diversity in Germany . 14 2.2.4 Institutional and legal framework and current programmes . 18 3. Objectives and Models in the approach to biological diversity . 21 3.1 Models for sustainable development . 21 3.2 Principles applied in environment and nature conservation policy . 21 3.3 Conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity . 22 3.4 Specific international goals and models . -

January / February 2001

FREE Volume 1 Number 1 January / February 2001 A BI-MONTHLY NEWSPAPER ABOUT THE HAPPENINGS IN & AROUND THE GREATER LOS ANGELES FOLK COMMUNITY “Don’t you know that Folk Music is illegal in Los Angeles?” –Warren Casey of the Wicked Tinkers Dancing in the Subway MUSIC & DANCE IN UNDERGROUND LA by TERRY SQUIRE STONE ere we are at the birth of a new adventure: were here for a trade show a new newspaper for an old tradition. A downtown and were look- newspaper for those of us who have been ing to kill a few hours around the folk music scene for a while, between seminars. Did as well as one for those who are new to I think they should go this community. And, it is a community in to NoHo or City H the realist sense of the word. Walk? Could I help Which brings me to the LA subway… them? They wanted Bear with me… to know my opinion! I recently had reason to use the Los Angeles Metro Then, there was Link system for the first time. The Metro Link is the LA the Orthodox Jewish version of Paris Metro, the London Tube. And, just like teenager from Woodland Hills LA, it is glitzy and expensive, without much “there,” who was out for his first adventure there. It goes only a short distance with a lot of fanfair, but alone. Everything from the pur- it suited my purposes; to get downtown from the San chasing of a ticket to the art on Fernando Valley while avoiding the traffic and the hassle the walls was a wonder to him. -

A Conversation with Sarah Hawker of the Lonesome Sisters by Frank Goodman (8/2006, Puremusic.Com)

A Conversation with Sarah Hawker of The Lonesome Sisters by Frank Goodman (8/2006, Puremusic.com) Like a marriage, like a boxing match, like figure skating, there is something magical in the duo paradigm. A trio never stands naked like a duo does. But in that nakedness lies a much more intimate and illuminating experience, especially in the rare instances of vocal resonance as one finds in The Lonesome Sisters. Sarah Hawker and Debra Clifford are to the music born, but in much different ways. Debra is a veteran of many old time country and bluegrass groups from upper New York State. She's a very strong guitarist and banjo player, and a superlative vocalist. Sarah grew up a closet singer, dwarfed by a deeply talented Virginia family on one side and musically adrift from a non-artistic family on the other. She tells a stirring story of how she came out as a singer through the death of her musical grandfather, Ben Hawker. She's the niece of Ginny Hawker, a highly regarded singer, and Tracy Schwartz, who was a longtime member of the trailblazing New Lost City Ramblers, who showed the world where old time music was at in the '60s, and for many years to come. The story contained in the following conversation with Sarah includes her fateful meeting with Debra Clifford at a camp of her aunt's. It should be an inspiration to all who have a voice within them that they would like to set free. As only a great duo will do, their music started resonating with other people immediately, the way it did and does with each other. -

Maps -- by Region Or Country -- Eastern Hemisphere -- Europe

G5702 EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5702 Alps see G6035+ .B3 Baltic Sea .B4 Baltic Shield .C3 Carpathian Mountains .C6 Coasts/Continental shelf .G4 Genoa, Gulf of .G7 Great Alföld .P9 Pyrenees .R5 Rhine River .S3 Scheldt River .T5 Tisza River 1971 G5722 WESTERN EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL G5722 FEATURES, ETC. .A7 Ardennes .A9 Autoroute E10 .F5 Flanders .G3 Gaul .M3 Meuse River 1972 G5741.S BRITISH ISLES. HISTORY G5741.S .S1 General .S2 To 1066 .S3 Medieval period, 1066-1485 .S33 Norman period, 1066-1154 .S35 Plantagenets, 1154-1399 .S37 15th century .S4 Modern period, 1485- .S45 16th century: Tudors, 1485-1603 .S5 17th century: Stuarts, 1603-1714 .S53 Commonwealth and protectorate, 1660-1688 .S54 18th century .S55 19th century .S6 20th century .S65 World War I .S7 World War II 1973 G5742 BRITISH ISLES. GREAT BRITAIN. REGIONS, G5742 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .C6 Continental shelf .I6 Irish Sea .N3 National Cycle Network 1974 G5752 ENGLAND. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5752 .A3 Aire River .A42 Akeman Street .A43 Alde River .A7 Arun River .A75 Ashby Canal .A77 Ashdown Forest .A83 Avon, River [Gloucestershire-Avon] .A85 Avon, River [Leicestershire-Gloucestershire] .A87 Axholme, Isle of .A9 Aylesbury, Vale of .B3 Barnstaple Bay .B35 Basingstoke Canal .B36 Bassenthwaite Lake .B38 Baugh Fell .B385 Beachy Head .B386 Belvoir, Vale of .B387 Bere, Forest of .B39 Berkeley, Vale of .B4 Berkshire Downs .B42 Beult, River .B43 Bignor Hill .B44 Birmingham and Fazeley Canal .B45 Black Country .B48 Black Hill .B49 Blackdown Hills .B493 Blackmoor [Moor] .B495 Blackmoor Vale .B5 Bleaklow Hill .B54 Blenheim Park .B6 Bodmin Moor .B64 Border Forest Park .B66 Bourne Valley .B68 Bowland, Forest of .B7 Breckland .B715 Bredon Hill .B717 Brendon Hills .B72 Bridgewater Canal .B723 Bridgwater Bay .B724 Bridlington Bay .B725 Bristol Channel .B73 Broads, The .B76 Brown Clee Hill .B8 Burnham Beeches .B84 Burntwick Island .C34 Cam, River .C37 Cannock Chase .C38 Canvey Island [Island] 1975 G5752 ENGLAND. -

Introductory Essay “Hearing History in Bluegrass's High, Lonesome Sound,” by Rachel Rubin, Professor of American Studies at the University of Massachusetts

Session Four: Country and Blue Grass Introductory Essay “Hearing History in Bluegrass's High, Lonesome Sound,” by Rachel Rubin, Professor of American Studies at the University of Massachusetts Bluegrass is generally considered a sub-genre of country music that developed in the second half of the 20 th century. Although for purposes of radio airplay bluegrass songs were programmed on country music stations beginning in the late 1940s, bluegrass as a musical form did not develop directly out of the generation of recorded commercial country music that preceded it. Rather, the two forms share the same roots in the traditional music of the Appalachian region and the Irish and Scottish ballads that informed it. The description commonly offered of bluegrass that distinguishes it from mainstream country music is its’ “high lonesome sound.” This phrase was coined in 1963 by New Lost City Ramblers co-founder John Cohen, who used it to name a short film he made about Kentucky mountain music. The “high lonesome sound” quickly became a familiar catch-phrase for bluegrass music's emotionally intense, soaring-to-the-point-of-audible- strain vocal style, a style that often gives even happy songs an undercurrent of bleakness. Musician Bill Monroe, considered the “father of bluegrass,” used to claim that he would practice a song by singing it as high as he could—and then go on stage and sing it a half- step higher. Monroe's boast seems to indicate that part of the bluegrass aesthetic is an underlying anxiety that you might not make it to that “high, lonesome sound”—and a combination of pride and relief when you do. -

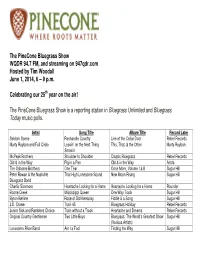

The Pinecone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and Streaming on 947Qdr.Com Hosted by Tim Woodall June 1, 2014, 6 – 9 P.M

The PineCone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and streaming on 947qdr.com Hosted by Tim Woodall June 1, 2014, 6 – 9 p.m. Celebrating our 25 th year on the air! The PineCone Bluegrass Show is a reporting station in Bluegrass Unlimited and Bluegrass Today music polls. Artist Song Title Album Title Record Label Seldom Scene Panhandle Country Live at the Cellar Door Rebel Records Marty Raybon and Full Circle Leavin’ on the Next Thing This, That, & the Other Marty Raybon Smokin’ McPeak Brothers Shoulder to Shoulder Classic Bluegrass Rebel Records Old & in the Way Pig in a Pen Old & in the Way Arista The Osborne Brothers One Tear Once More, Volume I & II Sugar Hill Peter Rowan & the Nashville That High Lonesome Sound New Moon Rising Sugar Hill Bluegrass Band Charlie Sizemore Heartache Looking for a Home Heartache Looking for a Home Rounder Boone Creek Mississippi Queen One Way Track Sugar Hill Byron Berline Rose of Old Kentucky Fiddle & a Song Sugar Hill J.D. Crowe Train 45 Bluegrass Holiday Rebel Records Junior Sisk and Ramblers Choice Train without a Track Heartache and Dreams Rebel Records Original Country Gentlemen Two Little Boys Bluegrass: The World’s Greatest Show Sugar Hill (Various Artists) Lonesome River Band Am I a Fool Finding the Way Sugar Hill The Nashville Bluegrass Band The Ghost of Eli Renfrow The Boys are Back in Town Sugar Hill The Nashville Bluegrass Band Blackbirds and Crows Unleashed Sugar Hill James King Thirty Years of Farming Thirty Years of Farming Rounder Russell Johnson Waltz with Melissa A Picture from the Past New -

Story Theme: American Music Subject: David Grisman Discipline: Music

EDUCATOR GUIDE Story Theme: American Music Subject: David Grisman Discipline: Music SECTION I - OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................2 EPISODE THEME SUBJECT CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS OBJECTIVE STORY SYNOPSIS INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES EQUIPMENT NEEDED MATERIALS NEEDED INTELLIGENCES ADDRESSED SECTION II – CONTENT/CONTEXT ..................................................................................................3 CONTENT OVERVIEW THE BIG PICTURE RESOURCES – TEXTS PERIODICALS AUDIO RESOURCES – DAVID GRISMAN DISCOGRAPHY – BLUEGRASS RESOURCES – WEB SITES VIDEO RESOURCES BAY AREA FIELD TRIPS SECTION III – VOCABULARY.............................................................................................................8 SECTION IV – ENGAGING WITH SPARK ...................................................................................... 10 Bluegrass musician and producer David Grisman (center) playing a show at the Freight & Salvage in Berkeley , CA. Still image from SPARK story, February 2005. SECTION I - OVERVIEW EPISODE THEME EQUIPMENT NEEDED American Music SPARK story “American Music” about musician and producer, David Grisman on DVD or VHS and SUBJECT related equipment David Grisman Computer with Internet access, navigation software, speakers and a sound card, printer GRADE RANGES Cassette player, CD player, or computer audio K-12, Post-Secondary program CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS Music MATERIALS NEEDED Access to libraries